Carbon Monoxide, The Silent Killer

When James Tyrrell dreams of a white Christmas, it isn't your usual Bing Crosby, Currier & Ives fantasy.

Director of the Jacobi Medical Center's Hyperbaric and Underseas Medicine unit, New York City's primary treatment center for carbon monoxide poisoning and smoke inhalation, Tyrrell knows firsthand what a nightmare the year's first major snowstorm can be.

"Last year, at one point, we counted 26 patients for carbon monoxide poisoning within a single 24 hour period," he says.

How so many patients ended up in the Bronx hospital's submarine-shaped pressure chamber is, of course, the real nightmare. Unlike lead, asbestos, and radon -- much-publicized household toxins that do their damage primarily through long term exposure -- carbon monoxide needs only a few minutes to ambush its victims. Odorless and colorless, it is a stealth killer that avoids the environmental and public health spotlight almost as easily as it evades the eyes and nostrils.

When carbon monoxide does finally make an appearance, however, the results tend to be cringe-inducing.

For New York City residents, the first cringe of the winter season came early this year. On Nov. 21 Bronx firefighters responding to an emergency call in the Morris Heights section made a grim discovery. When they got to the house of Patrick Williams, 26, they found Williams, his two month old daughter Patricia and his 54 year-old mother Erna Dennis all lying dead, victims of suffocation. According to a Daily News story filed the next day, the family's electric service had been cut off by Con Ed for nonpayment, and the family was relying on a gasoline-powered electric generator for power. Fire crew found the generator, sitting idle with an empty tank, in an attached garage.

Noting the lack of a carbon monoxide detector in the house, New York Fire Department inspectors have little doubt that the improperly ventilated generator and its resulting fumes were the chief culprit behind the deaths, says Battalion Chief John Salka, commanding officer of the responding fire units.

"If you don't have a smoke detector, there's a small chance you might smell the smoke in time," says Salka. "If you don't have a carbon monoxide detector, your chances of smelling carbon monoxide fumes in time are literally zero."

According to an August, 2002 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Assocation, carbon monoxide suffocation accounts for 2,000 American deaths each year. Local totals are hard to come by, but Dr. Michael Touger, a specialist at the same hyperbaric unit, says his facility treats the most severe carbon monoxide-related cases in the metropolitan area and handles up to 150 emergencies each year.

Many of those emergencies, including the Nov. 21 Bronx emergency that sent a surviving family member to Jacobi Medical Center's hyperbaric chamber, could have been easily avoided with the help of a home carbon monoxide detector. Unfortunately, getting those detectors into homes has been a slow-going process.

Ken Giles, a spokesperson for the Consumer Product Safety Commission in Washington, D.C., estimates that less than 15 percent of American homes have a carbon monoxide detector somewhere on the premises. Comparing that to the 93 percent of American homes that consistently report smoke detectors in industry surveys, Giles considers the number pathetically low.

"We think and recommend that every home should have an alarm," he says. "We also recommend that every furnace system be checked by a professional before you turn it on for the winter."

Getting that message out in any sort of a consistent manner is no easy task. New York state law mandates carbon monoxide detectors in all one- and two-family houses, condominiums, and co-ops built after January 1, 2002, but in a city like New York City, where the vast majority of buildings predate this cut-off, it falls on tenants to police their own dwellings. Even with printed warnings on heaters and furnaces, however, Touger estimates that a full third of the emergency cases that demand treatment in his unit stem from faulty heating and ventilation systems.

"We certainly are eager to engage any type of public education this time of year, because a lot of the cases we see should have been preventable," Touger says.

The sad irony of carbon monoxide poisoning, however, is that it usually takes grisly incidents such as last month's triple suffocation to send local residents to places like the Forest Ave. Home Depot on Staten Island, where detectors sell for $26 and up. Once there, the dust-covered plastic encasing each detectors offers a quick testimony as to why many still call carbon monoxide "the silent killer."

How Carbon Monoxide Kills

The primary challenge in elevating carbon monoxide to the A-list of feared chemicals is the molecule's own insidious nature. A natural byproduct of any combustion process involving carbon-based fuel, carbon monoxide is generally present any time you have a steady flame. Gasoline motors, natural gas furnaces, charcoal grills, and propane space heater all contribute varying amounts of carbon monoxide to the atmosphere. In most cases, however, circulating air keeps the amount of carbon monoxide molecules below the 9 parts per million threshold set by the Environmental Protection Agency as a suitable safety standard.

During the winter, however, windows seal up, aging furnaces and ventilation ducts go back to work, and snow rises to block automobile tailpipes. As the number of escape routes diminish, the amount of carbon monoxide in the air can quickly accumulate, rising to unhealthy, even lethal levels. Early symptoms of carbon monoxide exposure include nausea, dizziness, and splitting headaches. All are signs of the brain expressing its extreme discomfort at the lack of oxygen coming in through the bloodstream, but because they share a similarity to common flu symptons which also hit this time of year, many go overlooked until too late.

"Carbon monoxide is hard to diagnose," says Touger. "You have to have a high index of suspicion, especially this time of year."

Carbon monoxide's insidious nature extends to the molecular level as well. Carbon monoxide and ordinary oxygen molecules share a similar structure. Hemoglobin, the molecule responsible for transporting oxygen in the blood, binds aggressively to carbon monoxide almost as if tricked. As more and more oxygen-carrying hemoglobin molecules become carbon-monoxide carrying hemoglobin molecules, the amount of oxygen that actually reaches the bodies oxygen-dependent tissues starts to plummet. Slowly but surely, the body's own respiratory system is tricked into betraying itself.

"If you give a red blood cell the choice between binding to carbon monoxide and binding to oxygen, it will favor CO over oxygen 200 to 1," says Tyrrell, summing up the grim calculus.

The primary purpose of Jacobi Medical Center's hyperbaric chamber, he says, is to simulate the high pressure of a scuba dive. Just as scuba divers experience altered blood oxygen concentrations chemistry at extreme depths, a patient breathing pure oxygen inside a pressurized chamber will experience a surge in bloodstream oxygen. More oxygen means a higher likelihood that carbon monoxide, when it finally dislodges from hemoglobin, loses its place to an in-rushing oxygen molecule. With nowhere else to go, the carbon monoxide is then flushed out of the patients system through ordinary respiration.

Simply put, hyperbaric treatment can tilt the 200-to-1 ratio back into a poison victim's favor. "It's the quickest way to get rid of CO," Tyrrell says, noting the chemical shorthand for carbon monoxide.

Next to home heating systems and improperly ventilated appliances, the most common culprit in most poisoning cases is the automobile. Dr. Bob Hoffman of the New York City Poison Center says a statistical analysis of carbon monoxide-related calls coming into his center reveals two yearly "spikes."

"The first spike is early winter," Hoffman says. "That's when everybody turns their heaters on for the first time. The first couple of cold days always make us nervous."

The second spike comes after the first major snowfall. Drivers who fail to notice snow-blocked tailpipes often experience the initial symptoms of poisoning and call in seeking help. Such cases often don't require treatment once the victim has removed himself from an enclosed area. In the case of children exposed to carbon monoxide, however, automobile-related calls tend to be the saddest ones received at the poison center.

"A parent will put the child in a running warm car to keep it warm while he or she shovels out the tires," says Hoffman, relaying a scenario that plays out at least once a winter. "In the worst case, the parent mistakes the child's sudden unconsciousness for sleep, giving suffocation a better chance to occur."

Hoffman says his center has the budget and the media channels to get the message out. The only thing missing is the general sense of dread for these messages to tap into. Outside from the occasional tabloid headline, most New Yorkers can spend an entire year blissfully unaware of the menace lurking in their homes and cars. Even a city law mandating detectors in all homes, something Hoffman doesn't see coming anytime soon, would require a fatal accident or two to spur the proper outrage and enforcement.

"Every winter there's a lot of education both through the media and through the health commissioner's office: notices to check your boiler, check your heater, clean out the tail pipe in your car," Hoffman says. "Despite all that work, CO is the number one killer in terms of poisons, both in the city and across the nation."

Hoffman notes the recent suffocation deaths in the Bronx and expresses hope that, with the publicity such sobering events generate, the number of detectors in New York City homes will continue its slow climb.

"If any good ever comes out of anything, if you can save a couple lives because of these three, you've done a good job," he says.

Capital Budget

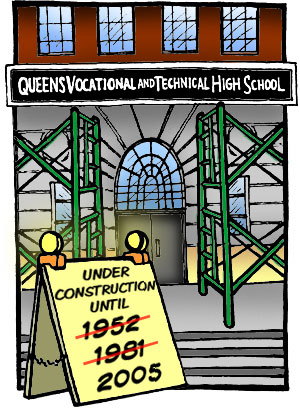

This year, Mayor Michael Bloomberg promised to do what the last eight mayors could not - build a new cafeteria and gymnasium at the Queens Vocational and Technical High School in Long Island City.

This year, Mayor Michael Bloomberg promised to do what the last eight mayors could not - build a new cafeteria and gymnasium at the Queens Vocational and Technical High School in Long Island City.

The school was first promised the new facilities back in 1948. However, decades of delay at the Board of Education, budget cuts, and debate among lawmakers over the mission of vocational schools stalled the project. For years, students have held gym classes outside, even in the winter.

Construction crews finally broke ground this summer and the new building is slated to open in September 2005. Mayor Bloomberg, who says he has cut school construction costs by a third, is now promising to complete other long-neglected school projects across the city.

Earlier this month, the mayor announced the most ambitious school construction plan in the city's history. He said he would spend $13.1 billion over the next five years to build 76 new school buildings for nearly 63,000 students. However, many doubt that the school construction plan will become a reality since half of the money must come from the state government in Albany.

The school construction plan is part of the city's capital budget. The capital budget, which totals about $6 billion a year, funds construction and repairs for the infrastructure of the city - the sewers, bridges, roads, subway lines, and wires and cables that keep the city running.

The capital budget, many experts say, is complicated, prone to cost overruns and delays, and largely ignored by lawmakers, the press and voters. It is also a delicate balancing act: spend too little and the city's infrastructure crumbles; spend too much and the city plunges further into debt.

"It is a real dilemma," said Preston Niblack of the Independent Budget Office. "The key is to find a sustainable level of spending. And we really haven't been able to do that."

WHAT IS THE CAPITAL BUDGET?

The city's capital budget is separate from the annual $44 billion operating budget, which covers daily expenses. The annual capital budget is approximately $6 billion; the city contributes $5 billion of it and the rest comes from state and federal aid.

By definition, a capital project involves the purchase, repair or construction of physical items that cost over $35,000 and must last for at least five years. Most of the city's capital budget goes to three areas: 33 percent goes to sewage and water systems, 20 percent goes to schools, and 20 percent goes to transportation. (See graphic for how capital money is spent.)

Where The Money Goes: NYC $49 Billion Capital Budget For the Next Ten Years

|

Every other year, the city issues a ten-year strategy that outlines the needs and goals for construction and repair over the next decade. Each year, the mayor presents an annual capital budget that proposes what should be built in the coming fiscal year and the three following years. A more detailed report of what is currently being built or repaired, called the capital commitment plan, is issued three times a year. (See Capital Budget Components sidebar below.)

Unlike the operating budget, which is funded largely by taxpayer money, most of the money for the capital budget comes from debt, usually through the sale of bonds. This debt must be repaid over decades to come.

"The rationale for using debt to pay for capital projects is that future generations will use and benefit from them, and so they should pay part of the bill," said Douglas Offerman of the Citizens Budget Commission.

Each year, the borough presidents are given a small portion of the capital budget to spend in their borough. The amount is based on population and the size of each borough. For example, Manhattan receives about $11 million and Queens receives about $28 million a year.

MISSING THE BIG PICTURE?

The capital budget goes through a long approval process and community boards, city agencies, the City Council, the borough presidents and the mayor all have input.

Still, the capital budget is often overlooked for a number of reasons. First, it deals with infrastructure, things like streets, sewers, and tunnels that most New Yorkers take for granted and notice only when they break.

Some argue that the capital budget process is further complicated and obscured by government bureaucracy. The 59 community boards meet each fall to determine neighborhood priorities, but critics argue that they often just pick from a list of projects presented to them by the city. The City Council used to hold separate hearings on the operating budget and the capital budget, but now the two fiscal plans are covered in one hearing. Long-term needs are often overshadowed by immediate budget issues.

"It should be a dynamic, planning oriented process," said Richard Anderson of the New York Building Congress. "But it comes across now as a paper process, with various city officials going through the motions."

In addition, the capital budget does not receive the same press attention given to the annual expense budget battles when every lawmaker and interest group in the city fights for their piece of the pie. Last June, the day after the capital budget was approved, it earned just a few sentences in New York City's five daily newspapers.

Finally, the capital budget deals with the long-term projects that can take decades to complete and can often run over budget or be delayed. Only a third of the money authorized each year is actually spent during that time frame. The rest is carried over into the next year and the completion date for projects are postponed.

"Capital budgets are unpredictable," said Joe Weisbord of Housing First, who urges funding for housing construction. "One way to manage the budget is to slow down a project or roll the money from one year to the next. But these decisions have serious consequences for the long-term needs of the city."

BRINGING HOME THE BACON

One of the few times New Yorkers actually hear about the capital budget is when politicians hold "ground breakings" or "ribbon-cuttings" on a new project.

Each of the 51 New York City Council members can request money for specific capital budget projects, and they represent some of the few tangible accomplishments a council member can point to come election time.

Last year, Bronx Councilmember Oliver Koppell lobbied for money to design a new library at John F. Kennedy High School, and to improve the libraries of three other schools. Queens Councilmember Joseph Addabbo Jr. requested $500,000 to build a skateboard park in Rockaway. And Brooklyn Councilmember Erik Dilan allocated more than $1 million for a youth center in Bushwick.

|

Two years ago, Brooklyn Councilmember Diana Reyna requested more than $1 million to build a new bathroom in Sternberg Park in Williamsburg. The budget item was approved, but the project was delayed in the city's process of soliciting bids from contractors. Dates for the start of construction were postponed three times, and work still has not begun.

"It is not just a matter of getting the funding approved, but continually monitoring the administration to make sure that the project is moving ahead," said Karl Camillucci, chief-of-staff for Reyna.

During a difficult fiscal crunch, local politicians say they sometimes find their pet projects slashed from the budget. Last year, for example, City Council members said the mayor eliminated capital money for library improvements and used it to plug a hole in the operating budget. The Office of Management and Budget said this is not true and all changes are agreed to by the administration and City Council staff.

STATE OF THE CITY

After the fiscal crisis of the 1970's, the city's infrastructure was in bad shape as many repair projects were delayed and new construction was abandoned.

The East River bridges became a poster child for municipal neglect. Repairs to the Williamsburg Bridge ended up costing about $600 million, some $400 million more than it would have if routine repairs had been made when needed.

During the 1990's, as the city's economy improved, the government spent more money - about $6 billion a year - to get its systems in working shape, or the technical term, in a "state of good repair."

But every improvement or new project is paid for with borrowed money and will cost New Yorkers for decades to come.

Every year, a significant portion of the city's annual expense budget goes to debt payments, the interests and principal on outstanding debt - and this amount grows each year. In 2002, the city paid $3.8 billion in debt payments. The Independent Budget Office estimates it will rise to $5.5 billion or nearly 20 percent of all tax revenue in the city by 2008.

Eventually, debt payments cut into services like senior citizen centers, library hours, and the number of teachers in the classrooms.

"Every dollar spent on debt service is a dollar that you don't spend on the day-to-day expenses of the city," said Douglas Offerman of the Citizens Budget Commission.

Today, facing another fiscal crunch and rising debt payments, the city is once again looking to cut costs.

But just keeping the city running is a monumental challenge. New York's infrastructure is old, it takes a beating from its 8 million residents, and it is still in need of billions of dollars in repairs. More than 40 precent of the capital money spent over the next ten years - some $17 billion - will go just to keeping the city's bridges, schools, streets, parks, and sewers in working shape.

CRITICAL ISSUES IN THE CAPITAL BUDGET

Education

Courts/Public Safety

Housing

In December of 2002, Mayor Bloomberg presented a plan to build or renovate 65,000 homes over the next five years. It represented the most significant housing proposal, many said, since 1986 when Mayor Ed Koch promised to build some 100,000 new homes.

While many housing advocates praised the mayor for his vision, they warned that the city's capital budget for housing was being slashed. The city's most recent ten-year capital strategy proposes cuts of $1 billion over the previous plan. The mayor hopes to offset the cut with federal funds from the Housing Development Corporation and the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, but this money does not fill the gap.

"We are facing the worst housing crisis in 50 years," said Joe Weisbord of Housing First. "Even with the mayor's plan, we are back to spending less [in the capital budget] than we planned to in 2002."

Parks

Capital funding for parks has remained fairly constant in recent years. However, parks advocates warn that the capital budget is being used to make up for cuts to the annual operating budget. For example, parks workers who do regular maintenance are being laid off, causing equipment to deteriorate more quickly. The city then makes up for this by ordering a capital overhaul, sometimes as soon as five years after the previous one.

"The parks department has to rely on capital money to replace equipment, rather than paying for ongoing maintenance," said Stephanie Elson of New Yorkers for Parks. "This will cost the city more in the long run, especially when you consider the interest being paid on the debt."

Sanitation

Since the closing of the Fresh Kills landfill in Staten Island in 2001, the cost of disposing of the city's 36,000 tons of daily trash has risen.

Over the next four years, the city plans to spend approximately $1.2 billion, a 21 percent increase over the past, to improve the city's marine transfer stations. The stations are located on the city's waterways, where the waste will be loaded onto barges and shipped to train stations that haul trash out of state.

Sewers And Water

Nearly a third of the capital budget goes to pay for sewers and water systems. Over the next four years, the city plans to spend $7.5 billion, more than $2 billion than it did over the same time period in the past. The city is investing billions in pipes and water mains because they crack and break hundreds of times a year. Some of the city's pipes were built 150 years ago.

One of the most costly projects is the massive water tunnel 3, which will bring drinking water from upstate reservoirs into the city. When the tunnel is completed in 2020, it will cost an estimated $6 billion. The tunnel construction began in 1969 and has been halted several times because of a lack of funds.

Debt for construction on sewers and water mains is backed by bonds from the Municipal Water Finance Authority and New Yorkers' monthly water bill.

Transportation, Roads, Bridges

Over the next ten years, the city estimates that it will have to spend $9 billion to maintain roads, bridges, tunnels, and mass-transit. As in the past, most of the money goes to big infrastructure projects like maintaining bridges. In fact, repairs to roads and bridges consume 84 percent of the transportation capital commitments. Street resurfacing will cost an estimated $2.3 billion over the next 10 years, an increase of 13 percent.

Between now and the year 2013, the city will contribute $748 million to the New York City transit capital budget, which pays for new subway cars and track repairs.

However, projects like the Second Avenue subway, the new lower Manhattan transit hub, and the extension of the 7 train into the west side of Manhattan are not included in the city's current plan.

*******

RELATED LINKS

• Capital Commitment Plan 2004

• Adopted Capital Budget 2004

• New York City's Ten Year Plan 2004-2013

• Guide to the Capital Budget from Independent Budget Office (in pdf format)

Lessons For

A year ago Mayor Michael Bloomberg put the finishing touches on a city budget that forced some $6 billion of deficit-reduction actions. That bold fiscal success - based mostly at the last moment on an 18.5 percent increase in property taxes - is in sharp contrast to the mayor's political loss with his three city charter proposals in the election this month. Yet the release of the city comptroller's annual financial report this month is a reminder that the mayor's budget balancing last year has worked remarkably well. At least in broad budget terms, city services in the 2003 fiscal year (ending June 30, 2003) remained stable - in spite of the severe economic and fiscal crises caused by national and city recessions, the World Trade Center attack, and a previous administration's tax cuts.

At the same time, buried in the comptroller's report and the sad little 2003 Charter Revision Commission exercise are some lessons for more democratic fiscal management. A public distaste for mayoral hubris seems to have fired up opposition to the nonpartisan election ballot question. But the defeat of the obscure ballot questions 4 and 5 reined in other dubious mayoral power grabs as well. Question 4 would have expanded mayoral discretion in city contracting, yet the city comptroller's new annual report cites several contracting problems - particularly in information technology procurement -- that suggest more, not less, outside monitoring. And question 5, an odd mayoral wish list of expanded powers, included the elimination of the preliminary mayor's management report (discussed in October's Finance column). Yet the comptroller report suggests current management can't even count potholes accurately.

Budget Stability and Services

The comptroller's report reflects the depth and vision in last November's budget modification. The property tax increase meant a full-year, recurring $1.7 billion revenue boost, helping the city to end the 2003 fiscal year with more than a $1.4 billion surplus. The carry-over of that surplus to the current year served as a big stabilizing factor. Political acceptance of the property tax increase -- and the new personal income and sales tax rates added in June 2003 for the current fiscal year's budget -- may or may not be evident in the recent council elections, but none of the re-elected incumbents seems to have suffered for their votes for new taxes.

The payoff for the revenue initiatives is clear in the comptroller's report. In several large service areas, budgets were stable or up substantially in 2003. If the budget numbers for fiscal year 2001 (i.e., the full fiscal year before September 11) are compared with those in fiscal 2003 (the first full fiscal year after September 11), the results range from an 18 percent increase in public education spending to just over a one percent increase in public safety and judicial spending:

· 2003 education spending was up 18.4 percent to $14.5 billion.

· Health spending rose to $2.7 billion from $2.3 billion, up 16.3 percent.

· Social services spending went to $9.8 billion from $9.2 billion, up 6.8 percent.

· Public safety expenditures hit $8.8 billion, up 1.2 percent from $8.7 billion.

Money, of course, does not guarantee services. But the few available numbers suggest stability and even some gains. The increase in education dollars is apparently largely the result of delayed salary increases. The number of full-time pedagogical staff, for example, was stable over the two years, although the ratio of students to pedagogues was up fractionally (11.2 to 11.6). As for educational performance results, indicators are few: the percentage of pupils meeting and exceeding standards in English language arts rose over two years nearly one percentage point in grade 3 (to 43 percent) but lost 1.2 percentage points in grade 8 (to 32.5 percent!).

In health, there are even fewer numbers in the comptroller's report. At the city's municipal hospitals, the number of billable outpatient day and emergency room visits was down slightly (from 5.7 million to 5.65 million, or just under one percent) from 2001 to 2003 - arguably a small improvement. There are also few statistics in social services. The number of persons receiving public assistance dropped from 497,100 in 2001 to 421,500 in 2003 (over 15 percent). Since 1994 the number of recipients is down 719,100, or 63 percent. (Neither the semi-annual mayor's management reports nor the comptroller's report can say where the former recipients are today.)

In the public safety area, the comptroller's statistics on service delivery point out that from 2001 to 2003 the number of uniformed officers decreased from 38,630 to 36,120 (- 6.5 percent). Nevertheless, the mayor's management report for 2003 (in pdf format) shows that major felony crimes fell by more than 14 percent during the same two years - an interesting opportunity for productivity analysis in a $3.5 billion agency.

Another section of the comptroller's report that is useful for measuring budget effects is the one on contracting. It shows that between 2002 and 2003, service contract expenditures (on everything from computer and child welfare services to legal and youth services) rose almost seven percent, from $6.66 billion to $7.02 billion. Most of the categories of health, social, and human services included here show little change. But there are some big-dollar exceptions to the status quo:

· Contracted homeless-family services were up 35 percent, to $297 million.

· Contracted individual homeless services went up 9 percent, to $148 million.

· Contracted employment services were up nearly 14 percent to $339 million.

· Contracted day care services were down 14 percent, to $331 million.

Contracting

The votes against ballot questions 4 and 5 were slightly less harsh than the vote against nonpartisan elections (64 percent and 66 percent against, respectively, vs. 70 percent). But they were also questions obviously of much less interest, with about 100,000 fewer people voting on 4 and 5 than the 471,000 who voted on question 3. The low turnout for the ballot questions (less than 13 percent of registered voters, according to The New York Times post-election figures) and the 100,000 non-responses on questions 4 and 5 among even those dedicated folks should be a signal that constitutional change is too important to trust to mayoral-driven summer exercises.

Coincidentally, the release of the comptroller's annual report provides some evidence that the few hardy souls who voted down expanding the mayor's contracting powers (#4) and eliminating the mayor's preliminary management report (#5) did the smart thing. For instance, the comptroller found that a $28 million amendment to an $84 million IBM contract "was beyond the scope of the original contract and accordingly required a new procurement. This contract is symptomatic of a greater procurement problem in which large computer contracts are written with vague scopes of work, loosely supervised, and not graded for performance. The Comptroller's Office is closely monitoring such contracts."

As baseball- and football-fan mayors look to new city subsidies for sports teams, it's always useful to keep in mind comptroller audits of these teams. Most recently, the comptroller found the New York Mets owed the city $4.6 million in rent because they "understated revenue by $18.8 million and overstated deductions by $35.4 million." The newest team in town, the Staten Island Yankees, is already following the big-league practices: The minor league Yankees owed the city Economic Development Corporation "$373,517 for various items including electricity, fees or signage revenue, and late payment charges." The audit also found "internal control weaknesses."

An audit of one of the Human Resource Administration computer systems -- its Auto Time System -- "found that the system was incomplete and cost $24.8 million, $15.2 million more than the initial contract amount." Nor did the audit see any way that $15.7 million in anticipated savings would be realized.

The Mayor's Management Report

The vote against ballot question 5 means, among other things, that the preliminary mayor's management report lives. This is a slightly awkward situation, since the mayor made it clear he thinks the document is not worth the trouble. What might invigorate the use (and value) of the February report is closer cooperation between the mayor and the City Council, the report's charter-mandated recipient. As noted in our October Finance column, the Council under Speaker Peter Vallone was an aggressive participant in the management-report process. The council held separate hearings and issued in-depth analyses, complete with extensive recommendations for the next round. Over the past two years, both these council efforts have been abandoned.

If the mayor and the council need any evidence to get back to serious work on the reports -- the best test of mayoral accountability -- the city comptroller's report is again a useful guide. A section summarizing some " Service Delivery/Program Performance" audits notes, for instance, that "an audit of [Administration for Children's Services] disclosed that the agency does not adequately monitor its 493 contracted day care centers."

Then there are the potholes. Potholes have often been the most visible (and most embarrassing) measurement of a mayor's management skills. The mayor's management reports keep records of potholes and repair operations, but look at what the comptroller found:

"Audit of [Department of Transportation] found that the agency lacks a useful standard for measuring the performance of its pothole repair operations. [The agency] took an average of 57 days - ranging from one to 2,494 days (seven years) to complete 1,774 sampled pothole repair ordersâ€|and some repairs are counted more than once in theâ€| pothole productivity figures."

Whether it's potholes, failed computer systems, the whereabouts of 719,000 former welfare recipients, or education performance standards, there is need for information, analyses, and self-examination in city government. We have budget stability for the moment, but particularly with no strong economic turnaround in sight, the city would gain from a higher standard of accountability in its work and its reports. The ballot voters had it right.

Glenn Pasanen, former associate director of City Project, teaches political science at Lehman College of the City University.