An Escape from Reality

William Glackens, 1912, oil on canvas.

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

On September 11, 2002, feeling an obligation to quietly commemorate the events of one year before, I set aside an hour to think about why I love New York. Central Park, the only backyard I have ever known, seemed the perfect place for such ruminations, so I settled down in Strawberry Fields and looked around. The park, as it turned out, was the absolute wrong place for me to celebrate the city. Complete strangers were smiling at one another! People were walking slowly, strolling even. This was not my New York. Sure, cabs were still racing through the 86th Street transverse and I spotted more than a few giant rats, but somehow, like magic, things were different in the park. That is exactly what I’ve loved about it, though, throughout my 20 years growing up here: The park offers me a place where the city rules are temporarily lifted.

Perhaps the change in rules was most apparent when I was young, because it was literal then. I did not have to hold my mother’s hand for fear of being "taken," there were no real streets to cross after looking both ways, and so I was pretty much free. In warm weather, I had the "ancient playground," where I filled my shoes and socks with sand within ten seconds of arriving. I had mountainous rocks to scale and Balto the brave medicine dog to inspire my adventures.

In the winter, there was sledding to do. Nothing else in Manhattan can offer a 5-year-old such abandon as flying down a hill, spinning in a saucer, until she runs out of steam or hits something. Nothing.

As I got older, and the intellectual and social pressures of New York began to pile up, I enjoyed the physical challenges offered by the park. For a respite from term papers about transcendentalism and music theory classes, I struggled to bike up the "big hill" on 110th Street without giving up and walking. And if the boy I liked at school turned out to prefer my best friend, I could always try to rollerblade down the hill by the "Stuart Little" pond without slowing down (I never quite mastered that). These days, my escapes from the fast-paced city involve trying to jog around the reservoir without being passed by anyone over 70 years old.

For me, the park is about suspended reality. For groups of middle schoolers at 1 a.m. on a Friday night, some controlled substance laws are temporarily forgotten (or so I hear). For young couples on an afternoon picnic, the complications of serious relationships are ignored for a while.

I now attend a college out west, where the whole enormous campus might as well be called a park. I can take pleasure in outdoor activities there, but something is missing. Without the nearby noise of 5th Avenue and the cerebral Metropolitan Museum, the park would not be so different, and without that contrast, the magic might be lost.

Sarah Lustbader, a NYC native and a student at Stanford University, is the 2003 Lenore Chester Searchlight intern for Gotham Gazette.

Recycling Revived

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg, as part of the last-minute budget negotiations with the City Council, agreed to resume plastic recycling (suspended a year ago), end the suspension of glass and yard waste recycling in 2004, and bring back Christmas tree recycling (suspended last fall), it was a decisive reversal from 18 months earlier, when the mayor’s elimination of these programs from the city’s program sparked outrage among recycling advocates, and seemed to spell a gloomy future for recycling in the city.

"The battle was tough, but we won the war," observed City Councilmember Michael McMahon of Staten Island, chairman of the council's committee on sanitation and solid waste, and a staunch recycling proponent.

Future battles remain. One twist in the current resumption of plastic service is an awkward every-other-week pickup schedule proposed by the Department of Sanitation. According to the recent City Hall agreement, that schedule will remain in effect from the first of August to the first of April, 2004, at which point, normal weekly service is expected to resume. Despite ongoing grumbles over institutional sandbagging, most city recycling advocates and their allies in the recycling industry are willing to look past such temporary obstacles and bask in the newfound resiliency of their movement.

Since the passage of Local Law 19, the 1989 ordinance that ordered the Department of Sanitation to set up a city-wide recycling program, recycling advocates and department of sanitation officials have butted heads over how to turn coins and bottles into cash. From the sanitation department’s perspective, recycling has put a consistent drain on both manpower and equipment. From the recycler's perspective, the sanitation department's own Soviet-like mania for one-size-fits-all solutions has made it difficult to tailor the city's recycling in a way that would make it more economically productive.

"It almost seems that whenever there was a decision that needed to be made, they made the wrong decision," says Marjorie Clarke, co-chair of the New York City Waste Prevention Coalition. "You begin to wonder: This can't totally be happenstance."

The end result, from the recycling view, has been a decade-long two-steps-forward, three-steps-back process that leaves proponents habitually wary whenever money comes into the conversation. That wariness has translated into strategies designed to stress the environmental benefits of recycling in a city that rarely sees those benefits firsthand.

That unwillingness to tread the bottom line proved a major handicap, however, in the wake of September 11. Faced with a huge budget deficit, Mayor Bloomberg bought into the Department of Sanitation's plan to save the city $56 million a year by ceasing plastic, aluminum and glass recycling.

"We have two recycling programs," said Bloomberg at the time. "One that works and one that does not." He was distinguishing between profitable paper recycling and unprofitable non-paper recycling.

A June, 2002 budget compromise saved aluminum but consigned plastic and glass to oblivion.

Reforming the Ranks

Talk to most city recycling advocates, and one event from the past year stands out. In November the Citywide Recycling Advisory Board (CRAB) and the Center for Economic and Environmental Partnership (CEEP) joined together as hosts of an industry roundtable at the downtown campus of Pace University.

A national summit for recyclers, consumers of recyclable commodities and industry lobbyists, the event represented the first major attempt to solicit outside help in driving home the economic sustainability of recycling.

"The city needed more education," says Clarke, a roundtable organizer during her tenure as chair of the Manhattan Citizen's Solid Waste Advisory Board (SWAB). "I figured that other cities were doing well. All we needed to do was bring in the information."

Clarke and her fellow organizers had little difficulty getting people to show up. In questioning both the financial and environmental merits of civic recycling, Mayor Bloomberg had in effect challenged the entire industry.

"New York is a bellwether for other programs across the country," notes roundtable attendee John Burgiel, national director of solid waste management for RW Beck. A Florida-base consulting firm, RW Beck has helped cities such as Denver, Cincinnati and Buffalo structure their recycling programs.

Burgiel and others would like to remind city officials of the great big market lying just beyond the five boroughs. Instead of going for the bulk discount, paying waste haulers to take both trash and recyclables, attendees proposed pushing the city into the role of auctioneer, selling off its plastic, aluminum and glass franchises to the highest bidder.

To get an idea of how it works, look no further than Visy Paper, a local subsidiary of Australian recycling giant Pratt industries. In 1995, Visy snuck its way into a city recycling contract by forging a deal with the Economic Development Corporation. In exchange for building a 200,000 square foot paper processing facility on Staten Island, Visy won itself a piece of the city paper stream. The facility opened in 1997, a year after Rudy Giuliani announced the impending closure of Fresh Kills. Since then, Visy has ramped up production, recyling 150,000 tons of city paper into corrugated boxes each year and paying $7 a ton for the privilege.

In other words, instead of the city having to pay companies to dump its trash – at a cost of at least $70 a ton – the city is being paid for the trash. Because of this, the arrangement with Visy translates into more than $11 million in savings for New York City taxpayers. On June 23, Visy and the mayor's office announced an ambitious 100,000 square foot expansion of the company's Staten Island facility to boost production even further.

A company called Hugo Neu has also forged ties with the city government. A major steel recycler, the New Jersey-based company offered to recycle the steel from the World Trade Center. It has since taken on a larger steel recycling contract with the city. Encouraged by the profitability of that enterprise, company executives made a play for New York City aluminum and plastic as well, offering to pay the city $5.10 per ton.

Considering that another company had put in a bid to charge the city $68 to get rid of that same material, Hugo Neu’s offer was one the Department of Sanitation could hardly refuse.

"This is not just an economic issue," said Hugo Neu general manager Robert Kelman at a May speech to the New York League of Conservation Voters. "This is a moral imperative."

What Next?

Moral imperatives aside, Hugo Neu's aggressive bidding has revived the image of recycling as a cost-effective enterprise. It has also prodded other local recyclers to seek their own portion of the city's mammoth recycling stream.

Carmen Cognetta, counsel to the council committee on sanitation and solid waste, hopes to speed the momentum.

"Recyclers used to be hesitant to deal with the city because they didn't get a good reception," Cognetta says. "I think once people see [the Hugo Neu bid] working, it will encourage more people to bid in the future."

One company eager to line up for city recyclables is Manhattan-based Sprint Recycling. Maite Quinn, the company’s managing director, says the market value for high quality paper runs well above the $7 per ton Visy currently pays for mixed paper and cardboard. If the city could find a way to segregate paper by type, it would boost profits even further.

"[New York] is not working as hard as other cities at getting the markets that do exist," she says. "We just put in a bid of $33 a ton for Jersey City's paper."

Another outcome of last year's roundtable has been a growing buzz over so-called "pay as you throw" funding systems. Under such a system, the city charges residents for trash pickup but not for recycling. In San Francisco "pay as you throw" has spurred the expansion of recycling streams in the realm of organic waste and kitchen compost. The city currently recycles half its waste, compared with New York City's 20 percent recycling rate in 2000-2001.

"'Pay as you throw' is a way to provide dedicated funding," says Robert Haley, recycling coordinator at San Francisco's Department of the Environment. "Come bad times or a budget crisis, you don't have to cut back recycling for lack of money."

Granted, San Francisco and New York are more than a continent apart when it comes to size, waste-stream burden and local markets for recyclable materials. Still, to get a hint of the future, New York reyclers can look to Canada's largest city, Toronto. Like New York, Toronto experienced the closure of its main landfill in the mid-1990s. Currently, the city exports about a fifth of its solid waste to Michigan. Through a combination of pay-as-you-throw and private contracts, the city is hoping to boost its recycling rate to 60 percent by 2006 and 100 percent by 2010.

"New York has challenges," says Lawson Oates, manager of Toronto's Solid Waste Management Division. "But it also has economies of scale that can be built in. That's an important factor."

Lawson, who also attended last November's roundtable, says he came away with a new respect for New York's waste stream. He recalls waking up at 3 a.m. to the sound of beeping sanitation trucks and workers clearing the enormous mound of garbage backs piled outside his hotel.

"I suddenly realized that nine floors wasn't as far up as I thought it was," Oates says.

Oates was equally surprised by the amount of manual labor that went into moving that waste stream. Oates says his own department has managed to boost productivity and rein in labor costs through wheeled bins in high density portions of the city. To stave off labor trouble, Oates' department has made sure to include union leaders in each step of the planning.

"With the four day work week, the union was wary but they eventually came on board," Oates says. "As a result, we've achieved economies and introduced some savings into our collection system."

Getting similar concessions out of the Department of Sanitation might be unlikely at the moment, but Oates' success has encouraged New York City planners to think creatively. Herein lies the final benefit of the recent waste management crisis: It has punctured the cultural hubris of a city used to viewing the outside world from a distance.

"For whatever reason, we have this mantra: We're New York. We're bigger than anybody. There's no other place we can learn from,'" Clarke says. "If you really think about it, half of New York is no different from any other large city. Only in Manhattan do you hit the problems most other cities never face."

Bloomberg: Savior or Shmendrik?

So how much credit should be given to Mayor Bloomberg, the man who, intentionally or unintentionally, forced the city's decades-old recycling program to prove recycling's economic sustainability?

For Resa Dimino, president of the Grass Roots Recycling Network and co-moderator of last November's roundtable, the answer is "not much." Dimino doesn't buy into the growing argument that the mayor's threat to suspend glass, plastic and even aluminum pickup in early 2002 was simply a case of managerial "tough love." Instead, she sees it as a costly example of brinksmanship in a city where residents have yet to experience the routine of a steady recycling program.

"I would argue that it would have been smarter to keep the program in place and go through the same kind of process," she says. "Instead, the city government just chose to ignore things until they reached crisis mode."

Others, such as McMahon, however, are willing to give the mayor the benefit of the doubt.

"I give the mayor credit in that he's the first mayor who admitted that recycling is a good idea for the environment and we can make it work financially," McMahon says. "Of course, we had to force feed him that a little bit. But in the final analysis he's doing the right thing by recycling."

Sam Williams is a NYC journalist.

Compstatmania

When 57-year-old Alberta Spruill died after a botched police raid on her Harlem apartment in May, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly reacted immediately. Kelly apologized for her death, Bloomberg spoke at her funeral, both men promised an investigation. And, in a response that has become familiar in New York, the police department vowed to look at the numbers -- in this case to create a database with information on police raids conducted as the result of search warrants. The police department, like so many other city agencies and city governments, was hoping that another thorny problem could be solved by using yet another variation of Compstat.

When 57-year-old Alberta Spruill died after a botched police raid on her Harlem apartment in May, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly reacted immediately. Kelly apologized for her death, Bloomberg spoke at her funeral, both men promised an investigation. And, in a response that has become familiar in New York, the police department vowed to look at the numbers -- in this case to create a database with information on police raids conducted as the result of search warrants. The police department, like so many other city agencies and city governments, was hoping that another thorny problem could be solved by using yet another variation of Compstat.

In 1994, Police Commissioner William Bratton launched Compstat, a program that used hard data and stepped-up accountability to try to stem lawlessness in the city. It was, said George L. Kelling and William Sousa in a paper for the Manhattan Institute, "perhaps the single most important organizational/administrative innovation in policing during the latter half of the 20th century."

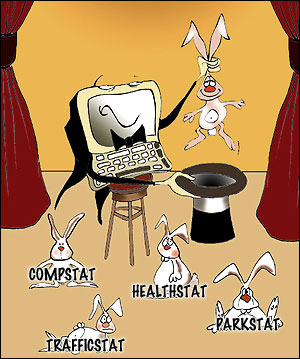

Officials in New York and elsewhere began copying it -- to fight crime but also to address many other problems as well. Soon, we had Healthstat and Parkstat and TrafficStat, and many more - with even more on the way.

Few seem to question whether there is a limit to the magic. But not everybody sees the trend as wholly positive. Indeed, some critics might go so far as to argue that Compstat actually played a part, albeit very indirectly, in Alberta Spruill's death.

THE BIRTH OF COMPSTAT

Collecting data and then mapping it has been used to identify trends and help find solutions since at least 1854, when a London doctor plotted the locations of more than 500 cholera deaths and saw that they clustered around one water pump. He had the handle of that water pump removed and ended the epidemic.

When William Bratton became police commissioner of New York City almost a century and a half later, he asked for a count of major crimes and where they occurred. A team of four police officers set to work transforming a rudimentary software program for small businesses into an elementary database with statistics about the seven crimes that municipalities must report to the Federal Bureau of Investigation -- murder, rape, robbery, felony assault, burglary, grand larceny and grand larceny auto. When the time came to save the file, one of the officers suggested naming it CompStat.

From this humble christening, something remarkable emerged. Police would enter crime reports into the computer system, which sorted them by type. Then officers pored over the weekly statistics to create maps and charts showing notable changes and emerging problem spots. Police department heads convened regular meetings to discuss the trends and strategies, inviting commanders from relevant precincts.

The sessions could be rough. As described by Craig Horowitz in New York magazine Jack Maple, the deputy police commissioner, "hammered every commander who came to a meeting unprepared. If robberies were up in the four-five that [commander] better have some suggestion to deal with it. Otherwise, he risked not only humiliation at the Compstat meeting but career derailment as well."

"In the Compstat meeting, people were accountable for getting the mission accomplished," said David Weisburd, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Maryland and the lead researcher on a Police Foundation study into the proliferation of Compstat. "The idea was, if you don't do the job, we are going to get rid of you, which was a radical idea. And if you do a good job, we are going to reward you." (The meetings are reportedly less contentious these days.)

But perhaps even more important than these meetings, write Kelling and Sousa, was the fact that Compstat spurred the development of local crime fighting strategies.

As Compstat evolved, crime fell sharply throughout the city, in all 76 precincts. The trend has continued. Overall, the serious crime rate (in pdf format) in 2002 was 65 percent lower than in 1993. For example, 2002 had 584 murders, compared to almost 2,000 in 1993.

Experts debate the true cause of that crime drop, pointing to the police department's pursuit of minor offenders during the Giuliani administration as well as demographic changes, the end of the crack epidemic and the strong economy. Some say that people in high crime neighborhoods, particularly young people, were angry at the violence and brought about the change themselves. Some critics note that other cities throughout the country also saw crime plummet in the 1990s - without Compstat.

Further, "the drop in crime [in New York] did not start in 1994," said Richard Holden (in pdf format), a professor of criminal justice at Central Missouri State University. Crime in the city peaked in 1990, Holden wrote, "and began its rapid decline from there. New York City was already in its fourth year of a dramatic downward trend in crime rates when it implemented its new approach."

"The data do not support a strong argument for Compstat causing, contributing to or accelerating the decline in homicides in New York City or elsewhere," criminologists John E. Eck and Edward R. McGuire have said.

But many officials and experts think, as Eli Silverman of John Jay College of Criminal Justice puts it, that Compstat "deserves some of the credit." The program received an Innovation in American Government Award, from Harvard's Kennedy School and the Ford Foundation, and officials in New York and beyond began looking for ways to apply it to other city scourges.

CHILDREN OF COMPSTAT

Over the past decade, especially in the past few years, city officials have implemented Compstat-like systems to address problems ranging from dangerous intersections to unruly inmates to negligent landlords.

First Compstat itself has evolved. "Compstat has changed over the years," said Detective Walter Burns, a spokesman for the New York City Police Department. "We've added different elements. The original concept was just dealing with precinct commanders. But one would come in and say, 'My problem is narcotics and I don't have a narcotics group. So bring narcotics into Compstat.' One says, 'I'm having a big problem with kids stealing cars.' Now auto theft is part of Compstat."

In New York, Trafficstat was among the first offshoots to take off. Also run by the police department, the program tracked accidents, arrests for driving while under the influence and other moving violations.

The Department of Correction implemented the Compstat model with T.E.A.M.S., its Total Efficiency Accountability Management System, and decreased overtime payments while increasing prison safety. The jails on Rikers Island became among the safest prison facilities in the nation, according to a report (in pdf format) about Compstat by the Rockefeller Foundation.

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation developed Parkstat. City parks were regularly rated for cleanliness and safety, and department supervisors were called upon monthly to account for their park's rating and discuss ways to solve problems. The percentage of parks rated acceptably clean and safe by the department rose from 47 percent in 1993 to 86 percent in 2001.

In August 2001, the Giuliani administration announced the Citywide Accountability Program which asked all city agencies to develop programs that implement the essential elements of Compstat. The agencies would collect data about their work and hold regular meetings with managers to find solutions to the problems revealed by the data. Currently, 20 city agencies participate in the program and publish data on the internet, where one can track all sorts of city statistics, from the numbers of complaints against taxi drivers to the number of malfunctioning off-track betting machines.

More "children of Compstat" appear every day. For example, the Mayor's Office of Health Insurance has been re-focusing Healthstat, a program designed to help uninsured New Yorkers enroll in publicly funded health insurance programs. In the first 18 months, participating agencies enrolled about 340,000 eligible New Yorkers. There are still 1.6 million uninsured New Yorkers, about 900,000 of whom are eligible for public insurance programs.

The Department of Education's new Office of School Safety and Planning will use elements of Compstat for SchoolSafe, a program that will identify schools with the highest crime rates and implement action plans.

And the Department of Transportation has M.O.V.E., a performance management and accountability system that meets twice each month to examine measurements of each operation's performance and to review its function and workflow.

And proposals for more Compstat type programs keep coming.

"We've done Compstat, let's do Jobstat," wrote Mike Wallace in his book 'A New Deal for New York.' Using the same kind of targeted analyses that helped reduce crime, he argues, we can help manufacturers stay in the city and nurture new kinds of industries.

Others think the Compstat approach can improve education in the city. "Changing the behaviors and attitudes of the school system toward parents and community won't be as easy," one-time mayoral candidate Fernando Ferrer, now president of the Drum Major Institute, said. "That is why we proposed a Compstat-like mechanism for measuring the system's attempts to create meaningful relationships with parents and communities."

The Department of Homeless Services and the Vera Institute of Justice is gearing up for Homestat. The idea, says department spokesman Jim Anderson, is to examine the incidence of homelessness in various areas, as well as factors that may contribute to homelessness. The department hopes that a better understanding of factors contributing to homelessness will help it develop strategies to prevent homelessness, not simply try to house those already out on the streets.

The reaction to the death of Alberta Spruill provides more evidence of how much faith officials now put in tracking numbers. According to the New York Times, the Civilian Complaint Review Board had suggested as early as January that the police department track and store information on search warrants executed by police. Spruill's death apparently spurred the department to move to put the proposal into effect.

Some have even suggested a Compstat for city government as a whole. "Rather than casually assert that government is efficient, City Hall should create an Office of Continuing Reinvention to aggressively keep pursuing new streamlinings and efficiencies - a CompStat for all services," former Public Advocate Mark Green has suggested.

OTHER CITIES

Meanwhile, the idea has spread across the country. By 2000, a third of the country's 515 largest police departments had implemented a Compstat-like program, according to the Police Foundation study. Bratton, now chief of the Los Angeles police, has taken Compstat west with him, instituting it in America's second largest city last fall.

"That's an amazing diffusion of innovation," said David Weisburd, the lead investigator of the study. "I compared it to diffusion ranks of the fastest growing innovations, agricultural innovations and social innovations like birth control. Most innovations take a very long time to spread. This one, in comparison, was extremely fast."

The researchers at the Police Foundation believe that Compstat's popularity came from its top-down authority model. "Compstat emphasizes putting pressure on commanders," Weisburd said. "The drama occurs with the higher-ups."

Like their colleagues in New York, officials in other cities have created Compstats for other problems -- or a combination of problems. Baltimore, Maryland, has taken Mark Green's suggestion and implemented Citistat, which tracks city government as a whole. City agencies provide regular data about their work to a central office that analyzes the data and creates reports for the mayor.

"The charts, maps, and pictures tell a story of performance, and those managers are held accountable," said Matt Gallagher, director of operations for Citistat. Since the program was implemented, Baltimore has experienced a 40 percent reduction in payroll overtime, saving the city $15 million over two years, while taking on such indicators of urban blight as graffiti and abandoned vehicles.

Cities from Miami to Pittsburgh will soon implement similar programs.

The Compstat mania has gone so far that one proponent, Heather MacDonald of the Manhattan Institute has turned it into a verb. In a November 2001 Daily News column urging that Compstat techniques be used to track down terrorists, MacDonald wrote, "The FBI's anti-terrorism efforts should be Compstated in every city where the bureau operates."

NO MAGIC BULLET

Nobody has been heard suggesting that Compstat can root out members of Al Queda. But Eli Silverman, author of NYPD Battles Crime: Innovative Strategies in Policing says it makes sense for city officials to try to extend the Compstat model. "It''s not rocket science. It's fundamental management accounting," he says, adding, "if it's done right it can be very meaningful."

But he offers some caveats. When the system is introduced, it has to be explained to the organization. The basic information -- the numbers -- must be consistent. "The managers have to feel top management is serious about it," Silverman says, and management has to stick to it. The New York Police Department, he says, has done most of this. In particular, he says, the department "has been consistent about it. That's one of the secrets of its success."

Even Compstat's most ardent proponents concede that Compstat-style programs do have some downsides. "What is not counted tends to be discounted," wrote Dennis Smith and William Bratton in a Rockefeller Institute Report (in pdf format) that considered some of the unintended consequences of the New York City Police Department's Compstat.

Commanders tend to overlook other indicators of police performance, such as civilian complaints and patterns of police misconduct, including too-aggressive policing and a lack of respect for citizens. Critics say such an attention to the numbers helped create the aggressive police tactics of the late 1990s, leading to the killing by police of Amadou Diallo and frayed relations between the police department and many black and Hispanic communities. And, though relations have improved, some have suggested that the recent incident with Alberta Spruill is a continuation of the imbalance in police attitudes and values.

Sidney L. Harring, a professor of law at City University of New York Law School, and Gerda W. Ray of the University of Missouri-St. Louis, wrote in 1999, that as the police strove to increase arrests, they did not keep track of how many people they stopped and frisked on city streets. "That all of this scientifically structured, aggressive police work could be pulled off without even the most rudimentary data about its result reveals the hollow core of the social scientific foundation of New York City's highly managed policing. Compstat is no better than its flawed database," Harring and Ray said.

Indeed tracking systems are only as good as the numbers that guide them. Last month, police officials revealed that many felonies committed in the 10th precinct in Manhattan last year were improperly reported as misdemeanors, making the crime rate in the area appear lower than it really was. The department was investigating a former commander and a sergeant for downgrading crimes in the precinct, which includes Chelsea.

Police department spokesperson Michael O'Looney told the New York Times that the distortions were too small to have any impact on the Compstat statistics. But critics reportedly say that as crime has fallen, police commanders feel intensifying pressure to drive the numbers even lower. Since Compstat went into effect, "at least five police commanders have been accused of reclassifying crimes to improve their statistics, which are reviewed at sometimes contentious weekly Compstat meetings," William K. Rashbaum reported.

After Philadelphia began using Compstat, some police officials there also changed crime reports to make the areas under their command appear safer than they really were. "If a person was punched in the eye, it might have been written up as a hospital report, so it didn't reflect a crime had occurred," said Philadelphia police department Inspector Bill Colarulo, who said that checks and balances have since been put in place to avoid such fraud.

Even without such fraud, the system makes some managers uncomfortable. "Poor managers hate it, because there's no where to hide. You are constantly being questioned about what you are doing," said Gallagher of Baltimore's Citistat. But it is not just incompetent managers who have been bothered by the harsh tone of Compstat meetings and the constant attention to statistical details. Holden of Central Missouri University blamed Compstat (as well as low salaries) "for its share of the drop in officer morale."

Such concerns are increasing as the paramilitary management style of the police department is extended into traditionally collegial and collaborative realms, such as education.

But the biggest problem with Compstat, said Holden, may simply be that we expect too much of it: "Compstat has ceased to be a tool and has become a religion dominated by high priests."

It is a religion that, given Mayor Bloomberg's well-known enthusiasm for technology, will only increase in municipal acolytes, whatever the reservations of the unfaithful.