Community Development Under A Kerry Administration

Joe Kreisberg, president of the Massachusetts Association of Community Development Corporations, recounts an incident that happened two or three years ago that defied political logic.

At that time Senator John Kerry had brought together a group of community folks in Massachusetts trying to jumpstart daycare centers and joined them with successful business people and other stake holders.

Kerry was trying to help care providers develop skill sets that would enable them to push through regulatory red tape and other obstacles that were blocking good faith efforts to build neighborhood day care institutions.

"I remembered thinking‚" Kreisberg said, "why is Kerry doing this? He is never going to run on these issues."

Kreisberg will never know for sure, but he was forced to conclude that Kerry had undertaken this project "because it was important to him and that he understood that he could use his position to make things happen."

At a time when the rhetoric of both presidential campaigns has focused mostly on the war in Iraq, the health of the national economy and various so-called character issues, Kreisberg hopes this experience represents an omen for a Kerry administration in the event Kerry is elected president.

The fact that you will never hear Bush, Kerry or any presidential media coverage specifically use the term "community development‚" makes it necessary to determine independently how that neighborhood-based universe of concerns -- housing, small business development, job development and social justice policy -- is addressed by each candidate. Last month this topic page examined one of President Bush's signature community development initiatives, "Opportunity Zones"

This month I will attempt to project how community development in New York would be affected by a Kerry White House.

Low-Income Housing Advocate

A significant policy difference between Bush and Kerry is in the area of housing.

Although both candidates offer ways to promote homeownership among low income people, Kerry has promised to maintain funding for the low-income housing program, HOPE VI, and the Section 8 voucher program, two targets of Bush budget cuts

Massachusetts-based fair housing and small business development advocates who have worked with Senator Kerry in the past describe a man who was personally engaged in the issues, well informed and a reliable ally on important legislation affecting low- and moderate-income communities.

Thomas Callahan, executive director of the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance says Kerry has for the most part been a leader in bringing not-for-profit and for-profit forces together in Massachusetts to build affordable housing.

Massachusetts has in fact been a model in this regard, partly because of its success in providing subsidies to developers to build affordable housing, even mixed income housing in the suburbs.

As an example of what Kerry is capable of, Callahan points to Kerry's co-authorship of the National Affordable Housing Trust Fund Act, proposed legislation that would take FHA surpluses and establish a permanent fund for housing production.

According to local observers, the bill is building momentum and stands a decent chance of eventually becoming law.

"The Trust Fund would have a tremendous impact on states like New York‚" where the cost of affordable housing production is so prohibitively high, advises Callahan. "Kerry was there‚" Callahan insists, championing and pushing this legislation "from the beginning."

Small Business Development's Ranking Member

A visit to the Kerry for President website and a look at his community development-related positions reveals a fairly wide range of thinking and policy development that was not always obvious from the debates or from his stump speeches.

Many people would be surprised to find out, for example, that John Kerry promises to raise the minimum wage from $5.15 to $7.00 by 2007; expand unemployment insurance to cover more people, provide more benefits for people between jobs and help laid off workers receive job training; protect workers' rights to organize a union; and strengthen whistle blower protections for "speaking truth to power."

Promising to usher in a "new era of opportunity‚" for small businesses and micro-enterprises, Kerry also says he will create a $170 million investment fund designed to make billions in capital and equity available to small business, including micro-enterprises with five or fewer employees and revenues under $500,000; establish tax credits to help offset the start-up costs of pension plans; provide tax credits that cover employer's share of payroll expenses; and help new venture firms provide financing and technical assistance in low-income communities.

In fact, one of Kerry's strongest community development credentials is that he is a ranking member of the U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship.

Mark Barbash, the director of the City of Columbus Ohio's development corporation, manages a Small Business Administration micro enterprise lending program and other loan programs for small businesses (Disclosure: City of Columbus Mayor Mike Coleman is a strong Kerry supporter).

Prior to his city job, Barbash used to lobby for increased federal support for micro businesses and small businesses in Washington on behalf of a small business development trade association.

Barbash was impressed with Kerry's grasp of "mind-numbing detail‚" and recounts giving testimony before Kerry's committee and finding Kerry to have a "good grounding on not just the SBA programs, but the difficulties that businesses face on the ground...He had a good understanding of what it took to run a small business; he understood that it wasn't just about capital and sometimes the best decision was not to go into business."

Kreisberg, who has also testified before Kerry's committee, said that Kerry distinguished himself at hearings because "he listened and actually made responses based on what people said."

Kreisberg points out that Kerry was a sponsor of the Prime Act which authorizes the Treasury Department's Community Development Financial Institutions Fund to provide support to micro-enterprise organizations and micro-entrepreneurs.

Furthermore he confirmed that Kerry was "very aggressive about getting loans to small business‚" as distinct from Bush who has not made access to capital a significant part of his small business development policy.

Perhaps most importantly, Barbash remembers Kerry talking a lot about workforce development and "investing in technology which can take ideas and move them into production."

According to Ken Adams, president of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, issues like these have as much resonance in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and Sunset Park as they do in Barbash's Columbus, Ohio. A Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce membership survey revealed that finding sufficiently trained and educated workers is a major concern for small business owners. Other insurance-related issues that have appeared on the campaign trail – the high cost of liability insurance, employee health plans and workers' compensation – are also the kinds of problems that small business owners in Brooklyn say they are expecting government to help solve.

Larry Vivola, co-CEO of the family-run ravioli manufacturing and franchise company, Fratelli Ravioli, says that health care and liability insurance are his two highest costs after salaries.

Fratelli Ravioli, which has eight full-time staff people, has endured a more than doubling of its liability insurance premium in the last two years and its health insurance premiums have risen thirty to forty percent every year for the past three years.

Gilbert Rivera, the founder of Park Avenue Building and Roofing Supplies, cited the same problems. He pointed out that his company's employee health insurance premiums have jumped from $90,000 to $220,000 over a five year period.

Although Kerry and Bush offer slightly different approaches, they both call for tort reform and have taken aim at reducing health care costs for small businesses.

In particular Kerry has proposed refundable tax credits for up to 50 percent of the cost of health care coverage for small businesses and their employees. Rivera, a self-proclaimed undecided voter, says that these insurance issues will play as important a role in the way he votes as his feelings about the war in Iraq.

Consumer Protector

Perhaps what most distinguishes Kerry's community development positions is his promotion of consumer policies designed to protect low-income people, such as his support for national legislation to fight predatory lending practices and his opposition to the weakening the Community Reinvestment Act. (Recently the FDIC made the news by proposing to relax the obligations of a large number of financial institutions under the Community Reinvestment Act.)

Although he sometimes wished it was "higher on Kerry's priority list‚" Thomas Callahan says that Kerry was a reliable ally to those seeking to defend the Community Reinvestment Act from routine attacks by policy makers and the financial services lobby.

Callahan's recollection was that it "was always a no-brainer‚" for Kerry to support the reinvestment act.

Reality Check

For those who believe in traditional liberal models of community development, which combine resources to lift people out poverty with a proactive social justice agenda, Kerry has always embodied the right politics.

And yet, there is reason to question how committed Kerry will be to this political legacy, especially since observers have watched his national campaign downplay his more left-leaning tendencies and appeal to the more moderate areas of the electorate.

Also, with a soaring budget deficit and Kerry promising tax cuts to the middle class, Bush's most credible criticism of Kerry is that it will simply be impossible for Kerry to pay for all his social largess.

Most importantly, with the war in Iraq, national security, health care reform, social security and other high profile demands on what would be his international and domestic agenda, it's pretty safe to say that some of Kerry's campaign proposals will be crowded out and never see the light of day.

Callahan admits that Kerry will have a much more difficult time in Washington, especially with a Republican congress, than he did in Boston, but Callahan refuses to make any predictions.

"It's hard to know. He's been a senator, not a chief executive.

He hasn't had to make tough budget decisions.‚"

Callahan holds out hope for initiatives like the Affordable Housing Trust Fund which would work "with an existing program, use surplus revenue and not require additional spending."

When it comes to strengthening consumer protections, Sarah Ludwig, executive director of the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Project, is more skeptical, mainly because she would hold a Kerry White House to a higher standard in tackling what she believes is this generation's civil rights issue.

Ludwig views community development essentially as a process of capital and wealth redistribution.

Financial services in this country, in her opinion, represent a "rigged system‚" that has allowed low-income areas to be over-run with debt and credit abuse and where nearly every consumer protection enacted since the New Deal has been dismantled.

Ludwig believes that these issues "resonate with Kerry and that he won't shy away from the complexity of the issues, but that corporate accountability is not something that he talks about.‚" Referring to interests as disparate as insurance companies, mortgage bankers, payday lenders and the securities industry, Ludwig doubts if "Kerry has what it takes to stand up to the financial services lobby and say we have to restore meaningful laws around consumer protections."

Kreisberg recognizes that a "quantum leap‚" in many of the areas that Kerry is concerned about is "only going to happen when they are at the top of his hit list and right now that's not the case.‚"

But despite these forecasts, community development advocates and voters in poor neighborhoods may find some comfort in the story that Kreisberg tells about the aspiring day care providers and business people who were brought together by Kerry in Massachusetts a few years ago.

Kerry confounded Kreisberg's expectations by taking on a low-profile cause where there was little political capital to be gained.

As Kreisberg recalls "He seemed to care enough and understand about what life is like in low-income communities even though it is below the political radar screen."

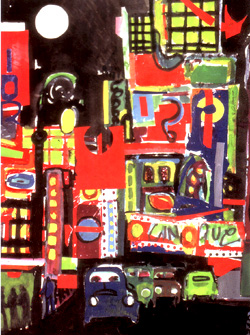

Times Square: 100 Years of Pleasure and Dissipation

|

Romare Bearden, Midtown, on exhibit at the Whitney. It Happened In 1904 |

Not long ago I visited Vienna. As soon as I arrived, I walked to the plaza at the center of town, the Stephansplatz, dominated by the dark mass of St. Stephen’s Cathedral. I was standing, or so I imagined, in the historical center of Europe – at least the Europe of 1900. It was very quiet. The Stephansplatz -- like the Place des Vosges or the Piazza della Republica or Belgrave Square -- is a serene place set aside for pedestrians, for all the great European capitals were fully formed long before the advent of the automobile. Standing there, I couldn’t help thinking of another square, which a melancholy bard named Benjamin De Casseres once described as a “ganglion of streets that fuse into a traffic cop.” I was thinking, of course, of Times Square, the crossroads of New York – of the planet, in its own estimation.

There may be some great popular tunes about the Stephansplatz but, somehow, I doubt it. The whole world knows Times Square, and not only through songs but through shows and movies and electric signs and radio and TV. And while other mythic urban places have about them the solemn grandeur that comes of tragedy and bloodshed, Times Square is a place associated only with pleasure and dissipation, even if at times the dissipation has had an ominous edge. Since 1904, when the subway opened up, when the Times Tower was completed, and when Mayor George McClellan officially gave the neighborhood its name – Times Square has been the world’s preeminent good time place.

We can trace Times Square’s destiny back to 1811, when a commission appointed by New York’s Common Council published an astonishingly audacious plan to tame the rocky wilds on Manhattan into a grid of streets. The commissioners noted that they had considered the use of “circles, ovals and stars” but had concluded that since “a city is to be composed principally of the habitations of men, and that straight-sided right-angled homes are the most cheap to build,” New York would have no such embellishments. The only exception to the city’s unvarying rectilinearity would be the diagonal stretch of Broadway, too prominent a thoroughfare to be erased.

From the beginning, New York’s entertainment district had tended to cluster around Broadway simply because the street was broad and ran more or less up the middle of the island. The city developed northward, and the development of new residential and retail neighborhoods tends to push the theaters, bars and restaurants farther up Broadway. By the 1860s, the city’s first theater district came into being at Union Square, where Broadway crossed 14th Street and a large waste area had been turned into a park. The juncture of Broadway and 14th Street came to be known as the Rialto because show people passed through it all day and night.

The Rialto kept moving northward. By the 1880s, the entertainment district had reached the junction where Broadway crossed 23rd Street at the base of Madison Avenue. The area immediately around Madison Square, a lovely park, was New York’s most refined shopping district. The lowlife beckoned from Sixth Avenue, where the elevated railroad carried New Yorkers of lesser ilk; bars and brothels, clustered along the side streets. But the worlds appear to have mingled relatively little.

The theaters moved up to where Broadway crossed Sixth Avenue, known as Herald Square, and continued onward; by 1893, Oscar Hammerstein, a cigar magnate, had built a great ocean liner of a theater in the prodigious gloom of 44th Street, just beyond the point where Broadway crossed Seventh Avenue.

|

View of a crowd gathered at Times Square in 1944. |

Times Square was the pool into which this vast new life emptied. The rich man went to the “lobster palaces” and the arch revues staged in the roof gardens, while the poor man paid a quarter to hear an immigrant like himself belting out a ballad in a vaudeville show.

At a time when new institutions like the department store and the office building were throwing men and women, rich and poor together as never before, Times Square was the ultimate leveler. And as we know from students of culture like Lewis Erenberg and Ann Douglas, this mixing and leveling gave a democratic, hybridized charge to music and dance and theater; the jeunesse doree of Fifth Avenue swung their hips and shoulders to ragtime dances that had bubbled up out of black culture.

And traffic. Times Square was not a “square,” a place carved out of the urban fabric, but the fabric itself, a gorge that traffic squeezed through in a great rush before disappearing out the other side. It was the city into its pure state, nature having been obliterated down to the last blade of grass. The Times Square character lived and died inside an asphalt triangle. Times Square gave birth to a race of men – and some women – for whom nature, and “naturalness,” was a con, and the only real life was the one made by men in buildings.

Times Square came increasingly to feel like a village, intricate and inbred, furnished with a complete set of folkways, mannerisms and habits of speech. We miss it now, of course – not the characters themselves but the sense of mythological possibility. Bulldozers chased the ghosts out of Times Square; or rather pornographers and drug dealers and loony street people chased them out first, and then the bulldozers cleaned up the mess.

|

The New Amsterdam Theater |

But whenever I despair, I remind myself that Times Square has had many incarnations over the last century; this one doesn’t have to be the last. Perhaps when the new paint starts to chip, even this Times Square will gain some power over our imagination.

James Traub is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and author of “The Devil’s Playground: A Century of Pleasure and Profit in Times Square.”

This article is excerpted from the spring 2004 issue of “The New-York Journal of American History, “ the semiannual publication of the New-York Historical Society.

Forgetting - and Remembering - the Slocum

The centennial of the General Slocum disaster provides an opportunity to ask a probing question: how did a disaster which claimed the lives of 1,021 people in the nation's largest metropolis become an all-but-forgotten footnote to history? By far the nation's most deadly peacetime maritime disaster, it was also New York's deadliest day before September 11, 2001. Yet whenever I asked anyone to name Gotham's worst calamity, I invariably got the same answer: the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911. That tragedy actually claimed far fewer lives (146) than the Slocum.

The story of the General Slocum tragedy begins in the thriving German neighborhood known as Kleindeutschland, or Little Germany, on Manhattan's Lower East Side. One of its sanctuaries, St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church on East 6th Street, held an annual outing to celebrate the end of the Sunday school year. The congregants usually chartered an excursion boat.

Wednesday, June 15, 1904, the day of the outing, dawned a beautiful spring morning. Shortly before 10 a.m., the General Slocum pulled away from its pier. It chugged up the East River, gradually increasing speed. Hundreds of children jammed the upper deck. The adults socialized while a band played German favorites

Then disaster struck. As the ship passed East 90th Street, smoke started billowing from a forward storage room. A spark, most likely from a carelessly tossed match, had ignited a barrel of straw. By the time crewmen notified Captain William Van Schaick – fully 10 minutes after discovering the fire – the blaze raged out of control.

The captain looked to the piers along the East River but feared he might touch off an explosion among the many oil tanks there. Instead, he opted to proceed at top speed to North Brother Island, a mile ahead.

The increased speed fanned the flames. Passengers began to jump overboard. Most did not know how to swim and drowned. The inexperienced crew provided no help. Neither did the life jackets, which were rotten and filled with disintegrated cork. Those who put them on sank as soon as they hit the water. Wired in place, none of the lifeboats could be dislodged.

When the boat finally beached at North Brother Island, it was almost completely engulfed in fire. The General Slocum left a grisly wake. The boats that followed it plucked a few survivors from the water but found mostly the lifeless bodies of the ill-fated passengers. The fact that they were young children only added to the horror. Rescue workers wept openly. When they finished counting the bodies, the death toll stood at 1,021.

The tragedy provoked widespread outrage, as survivors told of incompetent crewmen, useless fire hose and rotten life preserves, while questioning why the captain took so long to bring the steamer ashore.

Seven years later, the Triangle Shirtwaist factory burned and replaced the Slocum as the city’s great fire. Both fires killed mostly female immigrants, and aroused public wrath over callous corporate negligence. But the Triangle fire supplanted the Slocum tragedy in New York’s memory, even with its 85 percent lower death toll. Why?

First, the Triangle fire occurred during a time of intense labor struggle. Only a year earlier, tens of thousands of shirtwaist makers had staged a strike for better wages, hours and conditions. When 146 of them lay dead, there was no question as to who was to blame. This conclusion was reinforced when the public learned that the factory owners had locked the exits to keep the women at their machines.

Additionally, the Slocum tragedy was a “concentrated tragedy.” The majority of those killed were from a single parish and living within a 40-block area. Although their fellow New Yorkers were horrified by the tragedy, only a few were directly affected.

World War I also contributed to the forgetting process. Anti-German sentiment eradicated sympathy for anything German, including innocent victims of the General Slocum fire.

Finally, we must consider Gotham’s relentless pursuit of all that is new. “The present in New York is so powerful,” writer John Jay Chapman noted, “that the past is lost.” Indeed, within the city’s four centuries of history, only a handful of traumatic events are well known, chief among them the Draft Riots of 1863 and the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire. Perhaps, then, the real question is not why the Slocum fire is so little known but why the Triangle fire has been raised to such mythical status.

Whatever the explanation, the General Slocum never disappeared entirely. In 1922, the story achieved a bit of immortality when James Joyce included a half-page reference to it in his monumental work, Ulysses. In 1934, the Slocum gained a different sort of immortality in the film Manhattan Melodrama. It opens with a stunning re-enactment of the fire as a set-up for a story about two orphaned boys. In 1954, the New-York Historical Society mounted a small 50th-anniversary exhibit about the Slocum fire.

It was the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, that brought a renewed interest in the Slocum tragedy. Although one event was a willful act of destruction and murder and the other a tragedy born of negligence, greed and bad luck, there are many parallels. The most obvious was the profound shock and horror felt by the people of New York.

Another parallel was the selfless heroism exhibited by both uniformed personnel and everyday people on the scenes. Although no rescuers died in the Slocum fire, many risked their lives so that others might live.

A final parallel concerns the effort to build fitting memorials to the victims. Behind these initiatives lies a three-fold goal: to honor the dead, to provide the living with a place of contemplation and to ensure that society never forgets what happened.

Yet, the actual memory of traumatic events like the Slocum fire lives on only in the hearts and minds of those who experienced them. The only real memory of the Slocum fire died with the last living survivor. It will exist for succeeding generations, not as a memory but as a cautionary tale of greed and carelessness and a story of unspeakable loss and extraordinary courage.

Edward T. O’Donnell, associate professor of history at the college of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, is the author of “Ship Ablaze: The Tragedy of the Steamboat General Slocum.”

This article is excerpted from the spring 2004 issue of “The New-York Journal of American History,” the semiannual publication of the New-York Historical Society.