Flaws In The Screening Process For Foster Parents

The last of the children have departed. The house is empty. And you realize as you sit half listening to the television news that the years of changing diapers, wiping runny noses, and attending school field trips weren't all that bad. You liked being a parent. And you've come to realize that you have room in your heart and home for more children.

That is the story of most foster parents, according to Nicki McNeil of New Alternatives for Children, one of 42 agencies with whom the city contracts for foster care.

"Parenting is something they feel they do well and that they love to do," McNeil says. "They want the satisfaction of watching a child grow up."

But this is not the picture being painted by critics of the foster care system, who point to the latest tragedy as proof, the death of eight-year-old Stephanie Ramos. Stephanie was found dead earlier this month in a garbage truck. Police say her foster mother, Renee Johnson, placed Stephanie's 28-pound body in a garbage bag. As the Times reported, Johnson "has told the police that she panicked when the girl died. She is being held on charges of unlawfully disposing of a body and tampering with evidence. Law enforcement officials have said her home was filthy - covered with vermin and fecal matter - and are investigating whether neglect played a role in the child's death."

The question critics are asking is: How did this person become a foster parent?

THE SCREENING PROCESS

Becoming a foster parent does not look easy. One must be certified. The applicant must provide a medical report, income tax return, and three personal references. He or she must also be fingerprinted, undergo a criminal background check, and participate in a 10 week parenting training program, MAPP (Model Approach to Partnerships in Parenting).

Each person must also be assessed for personal motivations and life style, as well as the overall living conditions, during a "home study" which, says the Administration for Children Services, can take up to several months.

For all that, though, "it is an inherently flawed system of substitute care," charges Hank Orenstein, the director of the Child Welfare Project within the Office of Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum. The flaws, critics say, can be found in key areas of the screening process.

IN IT FOR THE MONEY?

Shortly after it was established in 1996, the Administration for Children's Services quickly set out to overhaul the child welfare system, focusing on what the agency calls neighborhood-based services. "Our aim is to place children close to home, so they can maintain social, cultural, identity ties, attend the same school, go to the same doctor," says agency spokesperson Mcclean Guthrie.

Designed to remedy one challenge, the shift to neighborhood placement may have created yet another.

Since many of the children who come into foster care are from low income areas, the agency began looking for foster parents who were from the same areas. And people from low incomes are more likely to be attracted by the stipend and other funds provide to cover the child's expenses.

To weed out those who might be in it for the money, the agency requires proof that a potential foster parent's income, whether from work or public assistance, at least covers their own expenses.

IS THE WHOLE HOUSEHOLD SCREENED?

When conducting the home study, the agencies aren't just interested in the home itself which must meet basic physical and safety requirements, but the hearts and minds of its inhabitants.

"A good foster care agency should screen for genuine, caring, and empathetic foster parents, and should get to know them as human beings," says Orenstein. And that means everybody in the home.

"Everyone is interviewed separately," says McNeil. And all family members living in the home who are over the age of 18 including the potential foster parents must be fingerprinted and processed through the State Central Register for Child Abuse and Maltreatment (SCR).

As for those under the age of 18, "they don't look closely at minor children in the home," says Orenstein. The law prohibits anyone from conducting a criminal background check on a minor.

THE SCREENERS

The screening process is only as good as the person who does the screening, and the caseload of caseworkers in New York City is well above the national average, which may explain why there is a 40 percent turnover in caseworkers.

PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTING?

Being a foster parent, like being social worker, is quite stressful.

"They might be relatively stable today, but a month from now, they might have some crisis," says Orenstein.

McNeil agrees. "Many are working full time. They may have someone who dies. They have to deal with their own grief while dealing with the child."

Sound psychological testing can help to determine who is mentally and emotionally fit to care for a foster child in both good times and bad.

One agency, New Alternatives for Children, which places children with severe medical and physical disabilities, requires that potential foster parents undergo psychological testing.

"Every prospective foster parent meets with our psychiatrist. It helps us help parents decide if this is for them. It helps us rule out possibilities of problems down the road," says Dr. Arlene Goldsmith, executive director of New Alternatives.

It is not certain whether Renee Johnson underwent psychological testing.

Though foster care agency executives like McNeil believe that most foster parents are "good hearted people who want to care for children," critics like Orenstein see a system that removes children from their parents for neglect, and places them "in a situation that's not any better.

"When a child dies it's a lightning rod, says Orenstein. "Tragically, some children die. But there are a lot of others that are not having a healthy or happy time. "

Carla Thompson is a Brooklyn-based journalist.

Welfare Reform

Nicole Thomas, a 29-year-old mother of two, has been on and off welfare for years. With a tenth-grade

education and a resume that includes jobs in fast food and retail, she knew she needed more education to find the kind of steady job that would enable her to support herself and her family. But when Thomas told city welfare officials she wanted to fulfill

her mandatory 35-hour per week work requirement by attending a GED (high school equivalency) program, they informed her she could attend classes only two days a week, and had to spend the other three days working as a receptionist at a nursing home.

Frustrated that the city's inflexibility would more than double the time she needed to get her GED, Thomas left the welfare-to-work program and started an internship at Families United for Racial and Economic Equality ("FUREE"), a grass-roots organization

that supports increasing welfare recipients' access to training and education. While she worries this may jeopardize her welfare grant, she hopes to pass the high school equivalency examination soon and then find a job so she can leave welfare permanently.

Nicole Thomas, a 29-year-old mother of two, has been on and off welfare for years. With a tenth-grade

education and a resume that includes jobs in fast food and retail, she knew she needed more education to find the kind of steady job that would enable her to support herself and her family. But when Thomas told city welfare officials she wanted to fulfill

her mandatory 35-hour per week work requirement by attending a GED (high school equivalency) program, they informed her she could attend classes only two days a week, and had to spend the other three days working as a receptionist at a nursing home.

Frustrated that the city's inflexibility would more than double the time she needed to get her GED, Thomas left the welfare-to-work program and started an internship at Families United for Racial and Economic Equality ("FUREE"), a grass-roots organization

that supports increasing welfare recipients' access to training and education. While she worries this may jeopardize her welfare grant, she hopes to pass the high school equivalency examination soon and then find a job so she can leave welfare permanently.

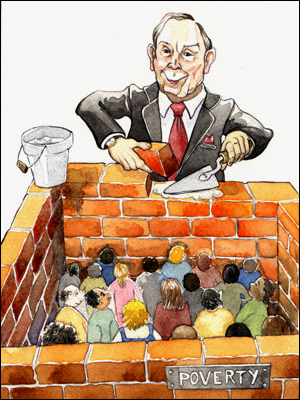

The lives of people like Nicole Thomas were supposed to get easier, not harder under Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Unlike his predecessor, Mayor Bloomberg seemed to understand the importance of addressing barriers to employment rather than single-mindedly trying to reduce the welfare rolls. Advocates talked optimistically about the mayor's more open-minded approach to welfare reform.

But the Bloomberg administration has since reversed course, taking aim at programs to increase welfare recipients' access to education, training, and permanent jobs. That the mayor has done so through litigation is particularly ironic in light of his frequent criticisms of advocates for pressing their claims through the courts.

Last year, the mayor sued over a transitional jobs program law that would have required the city to create 2,500 jobs for welfare recipients at government agencies and not-for-profit organizations for one year to help them make the transition to permanent employment. The suit did not attack the program's merits, but claimed it was "preempted" by existing state legislation granting authority over jobs programs to the city's top social services official, a Bloomberg appointee. In May, a state court judge ruled in the mayor's favor and invalidated the law.

The mayor recently returned to court to challenge the Coalition for Access to Training and Education law, also known as CATE, passed by the city council in April over his veto. This law represents the culmination of efforts to create a viable alternative to dead-end workfare assignments. It allows welfare recipients to satisfy welfare work requirements, which can reach up to 35 hours per week, by engaging in education or training activities, including college classes, GED programs, vocational training, adult literacy, and ESL courses. Previously, participation in these activities remained within the discretion of city welfare officials, who often resisted any alternatives to typical job search and workfare assignments. The mayor's legal complaint does not challenge the basic assumptions behind the law but rather boils down to a turf dispute with city council over who should determine welfare policy.

Experts widely agree that education and job training provide the best opportunity for people to leave welfare for lives of independence and self-sufficiency. Eighty-seven percent of welfare recipients in New York City who graduated from a four-year college stayed off welfare. While conservative policymakers tout the value of even the most menial labor, typical workfare assignments like sweeping streets and cleaning parks rarely lead to permanent employment in today's high-tech, service-oriented economy. In New York City, over 75 percent of employers require at least two years of college for any entry level job. Also, work requirements have previously served as a tool to cut people from the rolls for missed appointments or other forms of supposed non-compliance. While the rolls have dropped significantly in the city since the late 1990s, it is far from clear that welfare reform has actually reduced poverty. Education, along with employment skills and child care assistance, remain leading barriers to permanent employment. Of those remaining on welfare in New York City, over 50 percent lack a high school diploma or GED.

When Ramona Ledesma, who is originally from the Dominican Republic, applied for welfare she felt she understood better than anyone what had prevented her from finding a permanent job. But welfare officials immediately forced her to split her time between a workfare program and job-preparation classes. It never occurred to them, she recounted in her testimony before the city council, that the first step to prepare her for work was to enable her to learn English. To make matters worse, her case was closed twice due to administrative error, requiring her to start the process from the beginning each time.

In part, Mayor Bloomberg's rigid view of work requirements reflects a broader shift at the national level. Even before President Bill Clinton promised to "end welfare as we know it," the federal government had been seeking to reduce dependency by shifting the emphasis from welfare to work. A 1988 federal law imposed a comprehensive scheme of mandatory work requirements on welfare recipients, though the law also favored training and education programs over workfare. The real change came with the welfare reform act of 1996, formally entitled the "Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act." This act replaced the federal entitlement to cash assistance with a block grant to states and imposed a system of strict work requirements on recipients. While it permits states to choose whether college courses and other education programs can be applied towards an individual's work requirement, the act simultaneously prohibits states from counting those individuals in satisfying their mandatory overall state-wide participation rates.

Federal law still allows for innovative programs like the city's access to education and training law because at most 50 percent of the total welfare recipients in a social service district must currently participate in a work program -- and less if, as in New York, a state has earned credit for reducing its overall caseload by a specified level. Still, as a result of changes in federal law and the city's response, the number of welfare recipients in college has declined from over 25,000 in 1995 to under 5,000 today.

Despite the new jargon about "personal responsibility," trying to solve poverty by making poor people work is hardly innovative. Under the poor laws of seventeenth century England, assistance was limited to the "deserving" poor, a category consisting mainly of the old and infirm. Able-bodied indigents who refused to work could be convicted of vagrancy, confined to a workhouse, or publicly whipped. This moralistic and punitive view of poverty helped shape the development of welfare in America. According to Mimi Abramovitz, a professor at the Hunter College School of Social Work and expert on social welfare policy, opposing measures like the access to training and education law, "punishes single mothers for being single mothers." Although today's "work first" initiative portrays itself as inculcating welfare recipients with a good work ethic, it fails to provide the corresponding skills, education, and access to permanent jobs they need to succeed.

Then there is the old unwritten rule that those receiving public assistance must remain worse off than those with jobs. If welfare benefits were competitive even with minimum-wage salaries, so the argument goes, people would lose their incentive to work. By extension, single mothers would be getting an unfair advantage over the working poor if they received a free government handout while taking college courses or learning English as a second language.

Making welfare recipients work rather than improving their access to training and education has a further advantage, at least to the private sector. "By increasing the competition for unskilled, low-wage jobs, work requirements help keep wages down and labor costs low," says Abramovitz.

Mayor Bloomberg, who ordinarily opts for pragmatism over ideology, has recently adopted conservative slogans about the uplifting value of work that bear little relation to the hard evidence about workfare programs. A recent report by the Brookings Institution observes that only nine percent of those who enrolled in New York City's main workfare program found unsubsidized employment.

The mayor has expressed concern that local training and education laws could place the city in jeopardy of losing federal welfare dollars if work requirements are tightened when Congress takes up reauthorization of the 1996 act later this year. Yet the access to education and training law itself explicitly avoids that problem by requiring that participation rates remain within existing mandates. Nor does the city's current fiscal crisis justify the mayor's opposition towards the transitional jobs program, which was overwhelmingly funded by the federal and state government, with the city contributing only $4 million of the total estimated $50 million cost.

While work requirements have become a permanent part of the American welfare system, true reform will rely not on slogans but on innovative policies that address the real obstacles to permanent employment confronting welfare recipients.

Jonathan Hafetz is a public interest lawyer formerly with the Partnership for the Homeless

The Mayor's Plan To "Streamline" Social Services

In the relief at Mayor Michael Bloomberg's decision to restore some of the cuts he originally proposed to social services, the spotlight has shifted off proposals that may influence the field long after next year's budget is forgotten.

In his Executive Budget, the mayor proposed to "streamline" city social services by moving a number of programs from one agency to another. The best publicized proposal involved reorganizing AIDS services, by folding the Mayor's Office for AIDS Policy into the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and contracting out case management services now done by the HIV/AIDS Services Administration. After well-organized opposition and civil disobedience, advocates have approached the City Council about making the AIDS office a permanent unit of city government.

But there are many other units and services that will still move from one agency to another under the plan. This restructuring is meant to save money, but its potential effects on city spending -- as well as on clients and the local economy -- are unpredictable. Since in New York City, only one percent of the social service workforce is on the government payroll, it is the nonprofit social service agencies -- which get nearly two-thirds of their revenue from government grants and contracts -- that are most worried about the restructuring.

"I don't get the feeling that the city has put a lot of thought into the restructuring," says City Project's Bonnie Brower.

EMPLOYMENT SERVICES

Under the mayor's plan, the Department of Employment would be eliminated, and its services transferred to the Human Resources Administration. Public services are shaped by the agencies that control them. When job training comes out of a welfare agency, it is managed by a staff used to making clients prove that they deserve public benefits. This is not the mindset needed to encourage unemployed and underemployed New Yorkers at every level of income and education to use job-related services-the mandated use of funding from the federal Workforce Investment Act, which pays for most job training contracts.

The one exception to this shift is the Summer Youth Employment Program, which would go to the Department of Youth and Community Development. Providers of summer youth employment services may prefer dealing with the youth agency to waiting out the Department of Employment's delays: 96 percent of that agency's contracts were registered late in 2002.There is a possibility that the city will decide to move adult employment services to the Department of Business Services instead, which would demonstrate recognition that a well-prepared workforce is an economic asset. However, the Department of Business Services managed only $25 million worth of contracts last year, and may not have the capacity to abruptly add at least four times that amount to its responsibilities.

HUMAN RESOURCES ADMINISTRATION

The Human Resources Administration would take over many tasks currently performed by other agencies. For example, it would take over substance abuse services from the Department of Health and Mental Health; would take over child support enforcement from the Administration for Children's Services; and would take over the tasks of determining who is eligible for subsidized day care services, assistance with heating bills, and a home care program.

The restructuring plan would thus give the Human Resources Administration control over who receives several services that are not targeted to welfare recipients.

THE ELDERLY

The 105 senior centers that are located in New York City Housing Authority projects, about one-fourth of those citywide, would become programs of the Housing Authority, rather than of the Department for the Aging.

Instead of dealing with the Department for the Aging, elderly people in need of home care and the Home Energy Assistance Program would deal with welfare workers, as would low-income working parents seeking affordable day care.

AFTER-SCHOOL PROGRAMS

After-school programs would be transferred to the Department of Youth and Community Development, from both the Administration for Children's Services and the Department of Education. If after-school programs move from the Administration for Children's Services, with only 61 percent of its contracts registered late in 2002, to the Department of Youth and Community Development, with 86 percent of its contracts registered late that year, they may face longer delays.

The Department of Youth and Community Development would have to manage a sharp increase in its volume of contracts, a prospect advocates find unsettling. The logistics of the after-school contract transfer are not clear: many providers have one contract covering both pre-school children -- whose care would remain under the Administration for Children's Services -- and school-age children, whose care would shift to the youth agency. "Now they're going to rip out the school-age part of it, and we're not being told how," says Susan Stamler, of United Neighborhood Houses, whose settlement house members run a variety of human services. "It's wreaking havoc among providers."

Stamler's agency has recommended that the city maintain the quality and comprehensiveness of any after-school programs transferred, and develop an orderly process before any transition begins. "We're extremely concerned about avoiding disruptions during the school year."

Irma Rodriguez of Forest Hills Community House points out that the two agencies operate differently. "DYCD programs are typically based on a calendar year. ACS is based on the parents' year. They [ACS] understand the dynamics of working parents and their schedules."

Amid all the technicalities, the human dimension of contracted services can be forgotten. Susan Stamler brings the discussion back to the purpose of city-funded after-school programs: "Parents need to know their children are getting safe, reliable care that they can get to in their communities." Anything less will mean streamlining has gone too far.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits. She is currently on the staff of Bronx Independent Living Services.