Bridging Mass Transit's Budget Gap

In 1982, Richard Ravitch, then chairman of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, cobbled together $8.5 billion in city, state and federal financing to fund an MTA Capital Plan that helped turn the troubled system around.

On April 8, Gov. David Paterson announced that Ravitch would have the rare opportunity to try his hand again. This time, Ravitch will not be serving in an official MTA capacity but as the head of a blue ribbon panel of business, civic leaders and economists charged by the governor with recommending ways to patch the $17.5 billion hole in the MTA's $29 billion Capital Plan.

When the New York Sun asked Ravitch about his appointment, he said, "I am not sure it is anything but a Sisyphean task, but I will undertake it with energy and enthusiasm," an appropriate response considering that he has pushed the MTA's budget boulder uphill before, and today it's low on the slope once again.

The Capital Plan

The MTA's 2008- 2013 Capital Plan was released in late February, 18 months ahead of schedule, in accordance with the deal that formed the New York City Traffic Congestion Mitigation Commission, the panel that recommended congestion pricing. Many of its specifics, including use of revenues from congestion pricing, are now moot because of the state legislature's failure to approve the plan to charge people to drive in Manhattan. The capital plan, though, still stands as a fairly accurate predictor of the MTA's financial needs for system maintenance, improvement programs, completion of current expansion projects and expansion to provide new capacity.

The Capital Plan consists of three funding tiers. The first tier, the Core Program, allocates just over $20 billion to address the agency's core needs including bringing the systems to a state of good repair, normal replacement and system improvement. The vast majority of tier 1 funding, about $15 billion, would go to NYC Transit, with around $2.6 billion going to the Long Island Rail Road, $1.8 billion to Metro North, and $400 million to MTA buses.

The second tier allocates $5.5 billion for existing expansion projects like phase one of Second Avenue Subway construction, the Fulton Street Transit Center, the South Ferry Terminal and regional investments that would maximize the benefits of expansion projects.

The third tier focuses on new expansion projects, allocating $3.2 billion for computer-based train control and more cars on the 7 Line, Penn Station Access, phase 2 Second Avenue Subway construction and Jamaica Station improvements.

Meanwhile, rising construction costs have opened up a $3 billion gap in the 2005-2009 Capital Plan.

The MTA's financial situation extends beyond construction and equipment budgets, however. An analysis of the July four-year Financial Plan by New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli shows several items straining the budget. These include the debt service on bonds issued during the Pataki administration to finance past Capital Plans as well as the rising costs of healthcare and pensions, and the economic downturn. DiNapoli's report predicted that the operating budget deficit will grow from $965 million in 2008 to $2.1 billion by 2011.

Paying the Bill

To cover all these costs, the MTA has four potential funding sources: fares from subway, bus and commuter-rail riders; city, state and federal government contributions; an increase in existing taxes dedicated to transit, like the mortgage recording tax; and new revenue streams slated for transit, such as congestion pricing.

An increase in all four of these sources will almost certainly be needed if the MTA wishes to maintain the level of service, reliability, cleanliness and safety that 8.5 million daily riders have grown accustomed to and if the agency hopes to expand and improve the system.

The agency will almost certainly, however, have to raise fares more sharply than it did a few months ago if it hopes to keep up with the rate of inflation and balance the operating budget. DiNapoli, in his analysis, reported that the MTA has proposed another 5 percent fare increase for January 1, 2010. That said, it is very unlikely that the MTA will look to fare increases or fare backed-bonds to fund the Capital Plan.

Increased support from the city, state and federal government is always on the MTA's agenda. Former Gov. Eliot Spitzer had made it clear that he planned to fully fund the MTA's Capital Plan, although he never offered details on how he would do that. Paterson has been less explicit, though there are rumors in advocacy circles that another transportation bond act may be in the state's future.

On the federal level, in his State of the MTA Address, Sander pointed out that China spends 9 percent of its gross domestic product on infrastructure, while India aims to boost its spending from 3.5 percent to 8 percent in the coming years. The United States spends less than 1 percent of its GDP on infrastructure.

"Even after Albany and City Hall resume making significant contributions to the MTA Capital Program, it still won't be enough," Sander said, "We must join other national transit providers to persuade Washington to pitch in and provide a much higher level of federal support."

Increasing transit-dedicated taxes and fees will certainly be a big part of the equation. The economic slowdown, though, makes this a daunting task. The MTA will require increases in several transit-dedicated taxes and fees like the mortgage recording tax, the petroleum business tax and vehicle and license registration fees, to simply compensate for money lost, let alone to generate billions of more dollars.

Looking for Money

The heart of any Capital Plan funding strategy, then, in large part may be focused on identifying new transit-dedicated revenue streams. A 2004 report by the Regional Plan Association titled "Financing Options for the MTA Capital Program" looks at possible sources of revenue. It considers a few possibilities

--Traffic pricing, such as the congestion pricing plan: With the State Assembly having refused to even vote on Mayor Michael Bloomberg's proposal to charge a fee to drive in Manhattan during the work week, this seems off the table for the time being. However, according to Marc Shaw, former chair of the Traffic Mitigation Commission, Ravitch has not taken the option off the table.

--A gas tax: As gasoline prices have risen, some politicians, notably presidential candidates John McCain and Hillary Clinton, have called for doing away with the gas tax. Raising it in the current political climate appears unlikely.

--A commuter or payroll tax: The commuter tax, which raised $325 million the last full year it was collected, has popped its unpopular head out of the water repeatedly since it was drowned in 1999 by Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver. Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Kathryn Wylde of the Partnership for New York City, the Queens Civic Congress and others have at various times all floated the idea, but the general consensus is that the commuter tax is a non-starter in Albany.

Acknowledging this, the Regional Plan Association report suggests that the commuter tax could be refashioned into a mobility fee or payroll tax that draws on more earners and employers and is openly dedicated to transit. Based on 2000 income data, a 1 percent tax on wages after the first $50,000 could generate $820 million annually.

Looking Ahead

Tough times for the MTA mean tough times for the city and tough times necessitate tough measures. That could mean anything from service cuts to further construction delays to double-digit fare hikes to layoffs.

For now, we'll have to wait and see what revenue-generating proposals Ravitch's Commission recommends, what the 2009-2014 Capital Plan looks like and whether the economy warms, cools or stays where it is.

Despite the tough times, seasoned transit advocates are hopeful. "I'd be deeply depressed if we hadn't managed" to fund the capitol plan since 1982 said Gene Russianoff of the Straphangers Campaign. "If there is anyone who can find the funds needed to keep fixing transit now, it's Ravitch."

Graham T. Beck is the managing editor of Transportation Alternatives' StreetBeat, and a freelance writer. He lives in Brooklyn. Â

Bridging New York's Transit Gap

large cities such as Taipei and Bogotá.

While U.S. cities such as San Diego and Las Vegas have recently rolled out bus rapid transit, New York can learn more from the experiences of cities in the developing world cities, such as Curitiba, Brazil, and Bogotá, Colombia. Like the emerging megacities of the south, New York urgently needs better transportation for a dense population that already embraces mass transit - and a solution that can be implemented quickly and cost-effectively.

In other US cities, transportation wonks debate whether bus rapid transit, or BRT, a series of measures to move buses faster and reduce waits, can make buses sufficiently attractive to attract upscale riders and/or spur transit-oriented development. In much of the country, what transit there is consists of conventional bus systems that are underfunded, often ill-managed and, as a result, used only by people too poor, too old or too disabled to drive. Planners trying to popularize transit in car-dominated cities fret over whether BRT has enough cachet to overcome the stigma attached to buses and the people who ride them.

In New York, though, our challenge isn't attracting enough riders to make transit viable - it's providing enough transit to handle what is already an overflow customer base, not to mention the million new riders that PlaNYC anticipates. The epic saga of the Second Avenue subway illustrates a hard truth - building new subway lines in New York City is too slow and costly to address a meaningful share of our need.

Even if money were no problem, few of the major rail projects on the boards would do much to make our commutes faster or less crowded. The extension of the Number 7 train extension is typical - it's about enabling development on the far West Side, not about improving the lives of the people packed onto that train today.

Transit-starved in a Transit-rich City

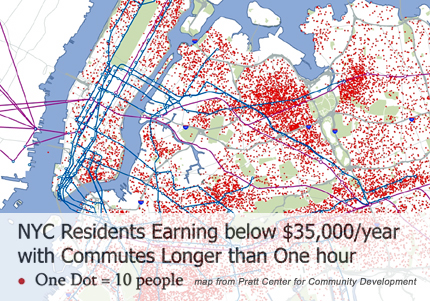

Meanwhile, three quarters of a million New Yorkers now travel over an hour each way to work. Two thirds of these commuters are on their way to jobs that pay less than $35,000 per year. These are folks who live at the far ends of subway lines or in places the subway doesn't go, or who commute to places the subway doesn't connect them to.

Rising housing costs have forced many low- and moderate-income people out of neighborhoods with good access to transit - such as Harlem, Williamsburg, Jackson Heights, to name a few -- to places like Soundview, East Flatbush, East Elmhurst and many others from which it's a bus ride or maybe two bus rides to the closest subway.

Another factor is where the jobs are. While jobs in the financial and creative sectors are concentrated in Manhattan, low- and moderate-wage employment in services, the trades and manufacturing is dispersed across the city. Most New Yorkers work in the same borough they live in, but unless that borough is Manhattan, this translates into long transit trips to work. An intra-borough trip that might take 20 minutes by car can take 45 minutes or more by bus because buses are slow and connections are poor.

As a result, poor transit access restricts economic opportunity. Workers with less than a college degree already struggle to find a limited universe of jobs that are a match for their skills; that universe is further reduced when they consider only jobs within a manageable commute from transit-poor neighborhoods. And opportunities for advancement through education are likely to be confined to the unaccredited colleges and trade schools that cluster around outer-borough transit hubs.

Long commutes also undermine family and community life. Low-wage workers seldom have the flexibility that allows higher-earning parents to juggle school and community meetings, get kids to after-school activities, doctor visits, etc., and handle the inevitable emergencies. When workplaces are an hour away from home, school and childcare, it's hard to find time for more than the most basic parenting tasks.

Many of New York's public housing developments are transit-deprived. Robert Moses, in particular, tended to build projects in isolated areas where land was cheap and local opposition was minimal. The Master Builder may not have cared whether his tenants had access to jobs, education, and services -- so to this day, tens of thousands of public housing residents remain stranded far from the nearest subway line.

BRT and Neighborhoods

As Phase 1 of the Second Avenue Subway inches toward completion, nobody in Morrisania, Canarsie or South Jamaica is holding their breaths waiting for the train to come in. But bus rapid transit -- "a subway running above the ground on rubber tires" could be in place relatively quickly and cheaply. Full BRT - with protected lanes, traffic signal prioritization and off-board fare payment - can move people at speeds and volumes that dramatically shorten travel times over long routes. Moreover, BRT will be accessible from its inception - to wheelchair users, seniors and everybody who has trouble climbing stairs - while the goal of providing access at every subway stop is still many years away. BRT will create an efficient no-transfer option for hundreds of thousands of people whose mobility is now limited to the radius a conventional bus can cover at a speed of 7.9 miles per hour.

Though dedicating lanes to buses presents a political challenge, BRT complements plans to reduce car use by making more efficient use of street space. There are a number of ways to ensure that the lanes are used by buses and buses alone. The lanes can be physically protected, but license plate cameras on the buses themselves are a more elegant solution -- letting the buses themselves nab the drivers who infringe on their space. However, enforcement cameras face an uncertain fate in the state legislature, where Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver has thus far resisted pressure to authorize additional red-light cameras in the city.

The City's First Steps

On March 25, Mayor Michel Bloomberg presided over the joint announcement of New York's first BRT route by Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan and Lee Sander, executive director of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Dubbed "Select Bus Service," it will replace limited-stop Bx12 service on Fordham Road/Pelham Parkway in the Bronx starting June 29. Most of the key BRT features are part of the package including off-board fare payment. Machines at bus stops will accept MetroCards or cash in exchange for a paper receipt. Following the example of many European transit systems, riders will be subject to random checks - but passengers will be able to board through front and rear doors, eliminating the bottleneck that forms as each rider swipes at the front door.

BRT-specific vehicles - low-floor buses with multiple doors - are still in the future, but the willingness of the transportation department and MTA to try "honor system" payment, as well as the department's painstaking work with local stakeholders to resolve conflicts around truck unloading and parking, signals a will to make this first route work. The more successful the initial BRT project is, Sadik-Khan reasons, the more communities will clamor for BRT to come to them as well.

Transit Funding without Congestion Pricing

Now that the state has failed to act on congestion pricing, when BRT will roll in the other boroughs is anybody's guess. The federal Urban Partnership grant that New York forfeited when the State Assembly did not vote on congestion pricing earlier this month would have funded a five-route pilot project, adding one BRT route each in Staten Island and Brooklyn, and two in Manhattan. (Resistance to the removal of some parking along Merrick Boulevard was so fierce that plans for a Queens route were put on hold, and a 34th Street crosstown route advanced in its place.) Of the $354 million in federal funds, $112 million would have paid for BRT.

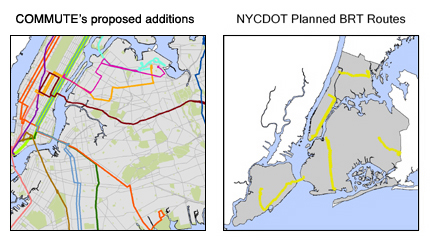

Meanwhile, a small but growing number of transit advocates and riders who know what BRT is are clamoring for more routes. COMMUTE! (Communities United for Transportation Equity), a coalition of community groups coordinated by the Pratt Center for Community Development, wants the BRT routes to cross bridges and connect the boroughs, making buses a more serious complement to the subway system.

The pilot program confined each route to its respective borough, so that the Rogers Avenue/Nostrand Avenue route in Brooklyn would serve a dense and underserved slice of East Flatbush, Crown Heights and Bushwick - but then dump passengers at Williamsburg Bridge plaza, presumably to elbow their way onto already full J, M and Z trains to get into Manhattan. Since the transportation department is already planning to put a dedicated bus lane on the Williamsburg Bridge, it would be logical to connect the Brooklyn BRT route to the also-planned First/Second Avenue BRT.

With both the one-time shot of federal funding and the projected $500 million per year in net revenues from congestion pricing off the table for the moment, BRT may be more important than ever. The MTA Capital Plan has, in words of Straphangers Campaign spokesman Gene Russianoff, "more hole than plan," with less than $12 billion of a five-year, $29 billion shopping list accounted for. As the rail and subway projects envisioned in that plan recede into the future, BRT makes more sense than ever. It will not prevent us from building light rail or subways in the future, but for now it makes intelligent use of the infrastructure we already have - our streets.

Joan Byron is the director of the Sustainability and Environmental Justice Initiative at the Pratt Center for Community Development.Â

How to Fix Our Transportation Woes -- Without the Fee

Anyone who has seen the horror movie "Carrie" knows that you can't turn your back on the screen until the credits have finished running. It is only with that reservation that I am willing to even consider life after the death of the mayor's proposal for congestion pricing.

On the day after the obituaries were written in New York's papers, word filtered down from Albany that the three men were still in a room and so the proposal could reach its bloody hand up from its grave. Despite such reports, it is my fervent hope that this bad idea has been laid to final rest by both houses of the legislature. Indeed, while the editorial writers rant at Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, it is clear that neither the State Assembly nor the Senate had enough votes to pass the plan.

Nonetheless, the problems that this plan sought to address remain very real. Though in the end congestion pricing morphed into a plan that was just about the money, the initially stated goals were all laudable: reducing traffic congestion throughout our region, cleaning our air and raising the critical revenue to support regional transportation. That's how I define the goals, in any event.

The Truth About Transportation

As we roll up our sleeves and put some thought into these problems -- before we put the necessary energy into solutions -- we ought to acknowledge at least three critical truths about moving people in our area. The first is that it is a regional issue requiring a regional solution. We move people from both the city and surrounding counties to New York's central business district and to other places of business. The solutions -- and the burdens -- ought to be regional as well. And it would be nice if we didn't trip and fall over a state line and could include our neighbors from New Jersey in the process.

Second, until we reach the days of the Star Trek transporter, people will move about -- and need to move about -- by bus, by train and by car. The absence of any one of these three would cause the other two to collapse. No one of them alone can shoulder the burden of moving millions of people to diverse locations.

Third, someone has got to pay for it. The needed infrastructure for all buses, trains and cars is massive and in constant need of upgrading and repair. The corollary of that is that the method of paying for it has to be both fair and effective.

In the spirit of the musical "Oklahoma," now is the time for the cowmen and the farmers to be friends. Whether you commute by car, bus, train, ferry or bicycle, a sense of mutual goals has to emerge. And whether you were for or against congestion pricing, a sense of mutual cooperation and respect needs to develop, together with a measured sense of urgency.

Paying for It

There have been many alternative proposals that address the city's traffic and transportation problems that do not involve the objectionable practice of allocating access to the core of our city according to who can and who cannot afford it. I have offered mine, and it is a proposal with a decent level of support from my colleagues on the City Council. It might be a good starting point for discussion. It has nine key elements. Let me give you the highlights.

I am proposing a one third of one percent tax on business payrolls, to be paid not only by businesses in the City of New York, but by those in Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester and Rockland counties as well. (If only we could include suburban New Jersey...) That means that a business with an annual payroll of half a million dollars would pay an additional sum of $1,667. This tax -- and yes, I know that tax is a dirty word -- would raise over a billion dollars in its first year, more than the projected revenues from congestion pricing and the $354 million in promised federal aid combined. The money would go to support transportation infrastructure of all kinds, including our subways, buses and commuter rail, and would have to include a guarantee that it be used fairly in the nine counties paying it.

Other broad based taxes could do this as well. For example, the Assembly Democrats have proposed a millionaire's tax. The key is that the tax be regional and broad-based, be effective and be borne fairly throughout the region.

Clearing the Jams

There are creative ways to attack congestion, both long and short term, by looking at its root causes. In the short term, we can move some city agencies out of the central business district to outer borough neighborhoods along train lines. We can change the culture of the taxi cab industry -- cabs account for 39 percent of the vehicle miles traveled in the business district are traveled by cabs, with a third of all those miles being racked up while the taxis are empty and cruising for passengers. Let's put a taxi stand on almost every block of the central business district. Let's make them more attractive by blowing in some hot air in the winter and cool air in the summer- and then require that cabs only pick up passengers at taxi stands except in inclement weather and at night.

Let's finish the subway link to Staten Island that was begun in 1923, so that Staten Islanders can actually opt to take a train to work in lieu of a gasoline guzzling car or bus. And let's finally finish the mission for which the Port Authority was originally created: the construction of the Cross Harbor Freight Tunnel, which would take a million truck runs off the roads of our City each year. And yes, Maspeth, we can find a way to make that work for your neighborhood too.

Finally, we need to take the absolute world leadership in developing the infrastructure to support the use of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles. These zero-emission vehicles could be in our marketplace as soon as next year. But who would buy one if there is no place to re-fuel with hydrogen? White Plains has just signed on to an experimental program, but our city can truly lead the way.

For the past year, congestion pricing was the Holy Grail, but it turned to be a false prize. We still confront the goal of sustaining our transportation system, cleaning our air and reducing traffic congestion. There is much to do.

I am ready. Are you in, Mr. Mayor?

Lew Fidler, a Democrat, represents Brooklyn's 46th district on the New York City Council.Â