Setting Standards for Green Neighborhoods

Recent successes with green buildings have spurred new efforts to make whole neighborhoods more sustainable and environmentally friendly. But is the attempt to develop a "green neighborhood" stamp of approval just an industry marketing gimmick? The pilot projects chosen in New York City -- including Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn, Willets Point in Queens and the Columbia expansion in upper Manhattan -- raise some serious questions about how green these proposed neighborhoods will be.

The national push for green buildings has been aided by the United States Green Building Council, a group with over 12,000 member organizations and 70 chapters. It includes real estate developers, environmental organizations and professionals. The group's aim is to promote the development of energy-efficient, healthy and environmentally friendly buildings. The council operates the voluntary LEED certification system that rates buildings as Certified, Silver, Gold and Platinum (the highest). Its Web site states that it "emphasizes state-of-the-art strategies for sustainable site development, water savings, energy efficiency, materials and resources selection, and indoor environmental quality." It describes the rating system as "a practical rating tool for green building design and construction that provides immediate and measurable results for building owners and occupants."

The Limits of 'Approved' Buildings

There are only 15 LEED-certified buildings in all of New York City. Ten are in Manhattan and, to the credit of city government, three belong to public agencies. This accounts for not even 1 percent of new buildings in the city. The cost of certification and the need to plod through the council's numerical rating system make it a non-starter for many developers, especially small and medium-sized firms. Non-profit and public developers can participate in the program only when they have the money and staff to navigate the rating system. While LEED may apply to existing buildings, interiors and community facilities, eight out of the 15 projects in the city are for construction.

Beyond all that, some experts have expressed concern that LEED certification is too narrowly focused on individual buildings and does not take into consideration the relationship of the building to the urban environment. After all, individual buildings can be environmentally friendly while at the same time contributing to destructive patterns such as suburban sprawl, displacement of viable communities and demolition of sound buildings and communities.

With that in mind, the Green Building Council recently developed standards that look beyond buildings to communities and urban regions. The new LEED for Neighborhood Development standards address these concerns. In theory, this is welcome development for New York City, where certification has too often been used as a way to market high priced real estate development and to protect buyers from the city's environment rather than helping to improve it. Now, combined with New York City's new green building law (Local Law 86) and new city building regulations, the certification standards for neighborhood development could begin to turn the gray city green.

The neighborhood development standards were developed by the Green Building Council along with the Council for New Urbanism and Natural Resources Defense Council. These national groups have played an important role in the critiques of sprawled suburban development and auto dependence. So the rating system gives developers points for: Smart Location and Linkage (30 points); Neighborhood Pattern and Design (39 points); Green Construction and Technology (31 points), and Innovation and the Design Process (6 points). In effect, the system favors development in built-up areas that have access to mass transit, projects that would reduce auto-dependence (i.e., "transit-oriented development") and designs that connect projects with surrounding areas and encourage walking.

Standards for the Big City

As admirable as these standards are and as successful as they might be in fighting sprawl in the suburbs, they run into problems when applied to New York City. Mass transit is just about everywhere in much of the city. A lot of new luxury megaprojects in Manhattan and Brooklyn are located near mass transit, but will not make any significant contributions to the improvement of service and so will increasing the demand on already over-burdened systems. Furthermore, these projects serve higher income residents, who are more likely to own cars than other New Yorkers, and the developers offer lots of parking to meet those residents' needs.

Six pilot projects in New York City are being used to test and develop the standards for LEED For Neighborhood Development. One, Melrose Commons in the Bronx, is being built in the context of a comprehensive community-based renewal strategy spearheaded by Nos Quedamos/We Stay, a local non-profit. The development strategy advocated by Nos Quedamos/We Stay focuses on community preservation, contextual development and truly affordable new housing. This is one among many grassroots efforts to bridge the gap between green building and local neighborhood development.

Citywide, the non-profit Home NYC provides a forum for such efforts, particularly for smaller buildings and in the outer boroughs where, after all, the vast majority of New Yorkers live. The most important virtue of such efforts is that they work with building owners and tenants and engage people in their local environments in the process of change. This is what is missing in most of the LEED pilot projects.

The other pilot projects are mostly large-scale developments that displace local people and businesses. The communities surrounding these developments have raised serious questions about the proposals and challenge whether they should be built in the first place — not a question that the rating system addresses. None of the projects is a good example of a long-term community-supported strategy.

Among the six pilots, at least three raise serious questions about whether the ratings are really anything more than self-promotion for developers -- who, after all, voluntarily agreed to take part in the pilot and, as with all LEED projects, put up the money to do so. The New York chapter of the Green Building Council includes among its sponsors some of the largest developers in the city, such as Related, Tishman Speyer and Silverstein Properties.

Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Yards is being promoted as "transit-oriented development," even though the project's environmental impact study found it will encourage auto use. In addition, while the developer says it may build LEED-certified buildings, the environmental review showed that the project will leave most of the area in permanent shadows.

Similarly, the city's project for Willets Point would create an isolated enclave, unconnected to Corona and other Queens neighborhoods, and set a bad precedent for brownfields cleanup by displacing viable businesses. Columbia University's West Harlem project would also create a separate enclave and faces strong opposition from local residents and businesses. Are these the right models for green neighborhoods?

The missing element in these three pilot projects is community planning -- engagement with residents and businesses to find ways to improve the quality of life, whether through new construction or preservation of the existing built environment. City government has an instrument for planning at the neighborhood level but it is atrophied from lack of use and often abused. Since the City Charter was revised in 1989 to permit community plans, only eight have been approved. In place of comprehensive neighborhood planning, City Hall proposes either large-scale developer-driven projects or projects by individual city agencies.

This could be addressed through a rating system for community planning comparable to LEED. It is hard, though, to imagine how the city would comply with such standards. Mayor Michael Bloomberg's long-term sustainability plan, PlaNYC 2030 is mostly a city-wide plan and did not include any significant involvement by the city's 59 community boards or the thousands of community-based organizations.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.Â

Expanding Wi-Fi Beyond Manhattan

Municipal wireless may be struggling in other cities, but New York City's Wi-Fi cloud is growing steadily. In addition to the fee-based access points in Starbucks, McDonald's and other venues, various civic groups continue to deploy wireless hotspots in parks, apartment buildings and lower-income neighborhoods. Late last year, CBS announced it would start offering an advertising-supported wireless Internet service in a tourist-heavy swath of Midtown. But there are many steps the city could take to promote these efforts, especially as it works to promote Internet access across the five boroughs.

Manhattan's Wi-Fi activity was on full display at a recent hearing of the New York City Broadband Advisory Committee, held at the Manhattan School of Music. The Downtown Alliance, NYCwireless, the New York Public Library and Harlem Wireless all spoke about their successes using wireless to promote economic development and increase quality of life.

The previous meetings of the committee, held in the Bronx and Brooklyn, featured little discussion of Wi-Fi beyond its availability at the Brooklyn Public Library, which now has Wi-Fi access in all of its facilities. Most of New York's Wi-Fi projects are in Manhattan, so it's no surprise that the recent meeting, held in that borough, featured a more extensive discussion of Wi-Fi and what steps could be taken to spread this important Internet access tactic to the other boroughs.

Strategies to Expand Wireless

Dana Spiegel of NYCwireless presented a number of recommendations on how to do this, including developing a fund to give grants of $10,000 or so to associations that want to offer free wireless but don't have the capital to launch the project. Once up, maintenance costs for Wi-Fi are fairly low, Spiegel said.

His organization has set up hotspots in a number of public parks. Since NYCwireless relies on host organizations to pay the startup and maintenance costs, the hotspots are concentrated in parks with well-funded support groups, such as Bryant Park. Similarly, business improvement districts that lack the resources of the Downtown Alliance cannot follow that group's lead in setting up public hotspots in lower Manhattan.

Spiegel also suggested streamlining the Parks Department process for approving such projects. And, since Wi-Fi access points still need to connect to the Internet, Spiegel recommends building new, publicly accessible infrastructure to reduce bandwidth costs.

Michael Lewis spoke about his Wireless Harlem Initiative, which is currently testing hardware to use in delivering Wi-Fi access throughout the neighborhood. He is frustrated by the city's Mobile Telecom Franchise process, which governs access to light poles and other city assets where he could mount wireless routers.

Vincent Grippo, chief of staff for the city's Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications pointed out that the department does have designated zones with lower fees, including most of Harlem, precisely to promote construction in those areas. The initial fee is $10,000 in the selected areas compared to $50,000 in most of the city and $100,000 in Manhattan below 96th Street. But Lewis contends that the fees were set up for cell phone providers or other big commercial efforts and represent a significant barrier for neighborhood initiatives like his.

Your Neighbor's Internet

The most common form of wireless Internet sharing is from neighbor to neighbor, where an in-home signal spills over through walls and windows, but this has several drawbacks. First, in most cases, it violates the Internet Service Provider's terms of use. (Some boutique providers like Speakeasy or Bway.net are more open-minded about their sharing policies.) Second, it usually involves using an unencrypted connection, which means private Internet traffic can be picked up by anyone in the area. And, third, it relies on neighbors who have a broadband connection and a wireless router.

Even though the city cannot condone breaches of providers' terms of use, it could seek to encourage neighbor-to-neighbor sharing. Rich MacKinnon, who built up Austin Wireless to a community of nearly 100,000 users by working with businesses and government agencies that could legally share their networks, suggests seizing the moral high ground. "In order for a city to ethically encourage neighbor-to-neighbor sharing, it needs to identify neighborhoods that are demonstrably under-served and identify broadband-enabled neighbors within that area or in neighboring areas," he said.

The city could work with broadband providers like Time Warner, Cablevision, and Verizon to establish "open zones" in the parts of the city with critically low broadband access where neighbor-to-neighbor sharing would be condoned. Unfortunately, City Hall is in the middle of video franchise negotiations with those providers, which means they are prohibited from discussing broadband with them because of the different way the federal government regulates the two services, according to Grippo.

But that shouldn't prevent non-governmental efforts to promote neighbor-to-neighbor sharing and educate people on how to operate an in-home hotspot securely and legally.

A Wireless Network

Beyond individuals' desire to access the World Wide Web, the city has a vested interest in getting people online, since it will advance Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plans to move many city services, including 311, online. This is why Andrew Rasiej, a member of the Broadband Advisory Committee who ran for public advocate in 2005, finds it disappointing that the half-billion-dollar NYC Wireless Network (NYCWiN) the city is constructing will not be open to the public, even though could well be among the most robust such networks ever constructed.

The original specifications for the network called for it to support multiple, simultaneous transmission of full-motion video or large files from and to anywhere in the city, real-time tracking of all city vehicles and control of traffic lights, continuous monitoring of air and water purity, transmission of patient vital signs from ambulances to receiving hospitals, and reliable voice communications to back up radio and cell phone signals. The network is operational in Manhattan below Canal Street. The information technology department expects the contractor, Northrop Grumman, to have the entire city covered by spring. The initial purpose is to serve the police and fire departments, but many other government agencies will eventually have access.

NYCWiN is not technically Wi-Fi, since it will use licensed spectrum. Wi-Fi operates over a portion of the airwaves that the Federal Communications Commission has designated as unlicensed, or open to the public for use with any approved device. Nevertheless, in non-emergency conditions, NYCWiN will have a lot of unused capacity that could help civic projects keep their bandwidth costs down, as Dana Spiegel suggested.

Rasiej also thinks the public could use citywide wireless access to contribute to government functions, perhaps by spotting potholes or suspicious activity. "There's still a firewall where elected officials understand that government is there to serve the people, but they don't think people can serve themselves," he said.

Rasiej is confident a wireless network can be made secure for shared use by both the police department and the public. Nicholas Sbordone, director of external affairs for the department of information technology, disagrees. "It needs to work the first time every time," he said because the network is for emergency situations where every second counts.

The city will release the results from the Broadband Advisory Committee hearings and extensive research conducted by Diamond Consultants. The release will include a plan for getting everyone in New York City full access to the Internet. As Diamond's team leaders have said Wi-Fi is by no means a silver bullet, but it can play an important role in a city's broadband strategy.

Joshua Breitbart is policy director for People's Production House.

Â

Daniel Doctoroff's Legacy

Daniel Doctoroff, the energetic and affable deputy mayor for economic development and rebuilding, announced in early December that he is resigning after six years in that post. The press and others immediately reacted with talk of a legacy comparable to that of Robert Moses, the 20th century master builder who developed many of the city’s roads and bridges, public housing, and parks. Mayor Michael Bloomberg stated that Doctoroff’s development projects, unlike those of Moses, were not linked to the bulldozing of neighborhoods.

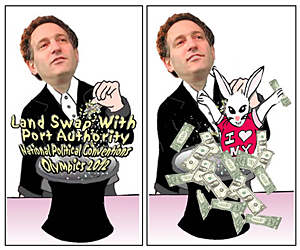

Doctoroff’s other admirers pointed to major development projects that took shape under his mandate as evidence that the deputy mayor had overseen an urban “renaissance” – Hudson Yards and Midtown West, the rebuilding at Ground Zero, the Bronx Terminal Market, new stadiums for the Yankees and the Mets, and proposals for Willets Point in Queens, the Columbia University expansion and Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn. While Doctoroff’s efforts to bring the 2012 Olympics and a professional football stadium to the city ultimately failed, his record as an indefatigable advocate for growth and development is unmistakable. His detractors no doubt breathe a sigh of relief that many more of his grand visions are far from becoming reality. The New York Times, the Observerand other local papers talked of a mixed legacy.

The Moses Analogy

Whatever Doctoroff’s accomplishments may be, the comparison to Moses is a stretch, and the talk of Doctoroff legacy premature by decades. Moses spent over half a century building public infrastructure while Doctoroff spent little more than a half-decade promoting mostly private commercial and residential development. Moses built enormous amounts of low- and moderate-income housing while Doctoroff’s affordable housing program has not been robust enough to prevent a net loss in affordable units. Moses developed broad citywide plans and strategies for his projects, Doctoroff relied heavily on zoning changesto spur private market growth. Moses of course thrived at a time when public subsidies for development were abundant, while Doctoroff worked at a time when development was expected to be initiated by the private sector with the government serving as facilitator, junior partner and deal broker. Making any judgment about Doctoroff’s legacy would be premature until the full impact of his projects and initiatives on the lives of New Yorkers can be assessed. Doctoroff made many proposals -- particularly his major one, the redevelopment of Midtown West -- that he himself claimed would take several decades to reach fulfillment. Much can change in that time. Also, it will be difficult to separate Doctoroff’s legacy from that of the mayor with whom he worked so closely.

Communities and Neighborhoods

There is one major striking similarity between Moses and Doctoroff – they both claimed a monopoly on grand visions and overlooked the diverse ideas emerging from the city’s neighborhoods. Doctoroff reached out to civic leaders and neighborhood groups in a way that Moses never did. But rather than encouraging a two-way dialogue between City Hall and those who might oppose its decisions, Doctoroff's outreach usually resembled a public relations campaign to sell people on decisions that were already made. According to Greenpoint/Williamsburg community activist Phil DePaolo, when the city was pushing its waterfront zoning in that area, “Doctoroff met just with the groups that would get housing and not with others.”

The mayor’s claim that Doctoroff, unlike Moses, spurred development without bulldozing neighborhoods is only partially true. Unlike Moses, Doctoroff did not enjoy the huge largesse of a federal urban renewal program that would have enabled him to buy up private property. In today's era of privately initiated development schemes, real estate developers for the most part have to do their own land assembly and bulldozing. The public sector's role is to approve the rezoning to make the development possible, and Doctoroff was more than willing to do that.

By standing by without intervening, Doctoroff gave the city’s blessing to a number of major projects in which the Empire State Development Corporation, a state authority, promised to use its powers of eminent domain to bulldoze residential and industrial properties. Forest City Ratner’s Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn and the Columbia expansion in West Harlem are the most notable of these projects. In Willets Point, Queens, the city itself proposes to use eminent domain to displace 225 businesses and 1,800 jobs in favor of a hotel, convention center, and giant commercial and residential complex. Any claims that Doctoroff promoted development without displacement must ignore the secondary displacement that occurs when large-scale private development forces rents and property values so high that people cannot afford to stay in their neighborhoods.

PlaNYC2030

Perhaps the strongest argument for a Doctoroff legacy is PlaNYC2030, launched on Earth Day 2007. This long-range plan was clearly a priority for the mayor, but Doctoroff’s office played a central role in developing it. It is the first attempt at a strategic long-range plan in the city since the 1969 Master Plan, which was never approved. It is certainly too soon to assess the results of a plan that looks to the year 2030, but Doctoroff’s approach raises questions about how long the proposals will survive after he and Bloomberg check out of City Hall.

The emphasis on sustainability and environment in the 2030 plan seems to flow from a long-term vision of large-scale real estate growth. Not long before the 2030 plan was released, the city’s Web Economic Development Corporation released a study by former City Planning Commissioner Alex Garvin that projected a vision of future growth around major transit hubs and over rail yards, leading to the dubious premiseunderlying the 2030 plan that the city’s population would increase by one million people. The Garvin report also noted significant deterrents to growth – lack of quality public space, traffic congestion, and pollution – that would later become a major focus of the 2030 plan.

In the plan, Bloomberg and Doctoroff pushed the concerns about long-term sustainability to the forefront in strategic planning for the first time. But without the predicted growth what will happen to sustainability and environmental and public health objectives? And will the laudable environmental goals be achieved only in those areas targeted for new development?

Even more problematic, however, is the fact that the next mayor, and his or her deputy mayors, could easily discard or overlook the 2030 plan. Even if they formally acknowledge the overall goals of the plan, they can ignore many specific objectives and programs. While any mayor has the power to undo the actions of his of her predecessor, the way Bloomberg and Doctoroff devised the 2030 plan make its future especially risky.

The plan was the product of the mayor’s office and its consultants, not an open, public process of decision making. Instead of subjecting the plan to extensive discussion, debate and a vote, Doctoroff's staff made colorful presentations throughout the city, received comments on those presentations and rarely engaged in a back-and-forth dialogue. Certainly encouraging discussion, debate and votes by all of the city’s 59 community boards and the City Council might have been messy. The result, however, would likely have been a richer and more developed plan reflecting the visions of many more New Yorkers. This, in turn, would have left made many more people committed to its goals and objectives. While the plan might have taken longer to approve, it would have stood a better chance of getting implemented.

The deputy mayor’s tendency to favor public relations over community dialogue seems to have been central to his style. A community board member in Brooklyn, who asked to remain anonymous because she is looking for a job in the public sector, told me, “Even in the Giuliani administration, which wasn’t interested in talking with communities, we could talk frankly with some city officials, but with Doctoroff it was all show….It was all about him, his rezoning and his development.” This person noted that when Doctoroff first met with community representatives to promote the Olympics 2012 plan, he was much more open to discussion, perhaps due to the premium placed by the International Olympic Committee on having sites that would remain as lasting legacies after the games are over.

Doctoroff’s Future

Many press reports about Doctoroff’s resignation and new position as president of Bloomberg LP, the media company founded by the mayor, centered around potential conflicts of interest because of Doctoroff’s intention to remain involved in the Hudson Yards, Queens West and other large-scale developments that he helped to shape. City conflict of interest rules restrict the direct involvement former city employees (paid and unpaid) can have with projects they worked on while in government. While Doctoroff is waiting for a ruling by the Conflict of Interest Board, most commentators seem to have missed the more important issue.

The more serious question for city policy – and this is clearly a legacy question – is whether Doctoroff has successfully blurred the lines between public and private sector to the point that public officials at the highest levels no longer have to be held responsible for representing anything that might be vaguely denoted as the “public interest.” Doctoroff’s close personal ties to the CEOs of the city’s largest developers, who have benefited from rezonings, tax relief and subsidies from the city, may not strictly violate any laws, but when the discussions that matter and lead to policy decisions are made in the board rooms and not the community boards, the temptation to act in the interest of private developers is great.

In an interview with Dominick Carter of NY1, Doctoroff spoke proudly of the expanded “portfolio” of agencies that Bloomberg had placed under his command at the start of the mayor’s second term. But was this former investment banker thinking of the agencies under his mandate in terms of the banker’s bottom-line or the public official’s mandate to serve the city and its neighborhoods?

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.Â