Neighborhood Banking Is About To Change

Imagine this: You walk to the corner store with your paycheck loaded on an electric card and slip it into an ATM-like machine. You take out a short term, high interest loan, download $60 into a savings account, transfer 40 bucks to your checking account, pay your electric bill, send fifty dollars to your sister who lives overseas -- and, oh yes, purchase that George Forman grill you’ve been eyeing. Finally, the machine spits out $31.35, coins and all, in cash that you requested. You do all this with one swipe of the card.

What is so tellingly futuristic about this scene is not the technology – we’re pretty much already there. It’s the virtual walls you just crashed through which, for now at least, separate various forms of financial and commercial transactions.

No walls have arguably been more impenetrable than those between banks and check cashing stores, more politely known as financial service centers. Like the kind of neighborhoods they are associated with, check cashers have operated for years on the other side of the tracks from bank branches, kept apart by regulatory boundaries and divergent business cultures.

But lately, driven by new technologies and a growing appreciation for the enormous, untapped profit and market opportunities in low-income neighborhoods, maverick providers of traditional banking services and check cashers have been taking pages from each other's playbooks and, in some cases, even collaborating. This experimentation will not only shape the course of neighborhood banking in New York and nationwide, but also redefine who and what is considered part of the banking mainstream.

Different Worlds

Commercial banks, thrifts and even most credit unions have long looked down their noses on check cashing operations, and, by extension, the predominately low-income people who use them, concluding there was either too little profit to be gained, or too much respectability to lose, in this gritty business.

On the other hand, check cashing operations, which offer products and services like money orders, pre-paid debit cards, utility payments and remittances, dominate certain inner city turfs by deliberately shunning the alleged white collar elitism of the banking industry. The 660 check cashing centers in New York specialize in serving customers in search of a simple financial transaction, rather than the institutional relationship sought by retail bankers.

Despite their different worlds, a few banks, such as Chase and Banco Popular, have over the years attempted modest, fairly low-impact, forays into check cashing or have, on occasion, purchased check cashing operations. Yet none have brought non-traditional financial services into the core of their business or have used these so-called “fringe” services to link customers to banking products.

Outside New York, however, some banks have been testing check cashing services in their branch lobbies alongside traditional teller lines and are creating new financial service prototypes.

Pioneering In The Bronx

Taking careful note of developments in areas such as California and Ohio, the Checkspring Community Corporation, headquartered in the Bronx, currently has a bank charter application pending in New York State. If its charter is approved, Checkspring will be poised to introduce a more fully integrated bank/check casher business model, the likes of which the New York City market has never seen.

Some of this territory has already been traveled through a collaboration between RiteCheck, a prominent check cashing chain, and Bethex Federal Credit Union, both of which serve low-income populations in the Bronx. In 2001 they piloted a program in which members of Bethex accessed their accounts through RiteCheck storefronts and cashed their checks at RiteCheck for free or at a reduced fee (In PDF Format) . The program worked so well that RiteCheck is expanding it to include partnerships with several new credit unions.

As options for electronically transmitting cash increase, and use of the traditional check diminishes, check cashers are trying to find new ways to engage customers and add value to their lives. In May of this year the Financial Services Centers of America (FiSCA), the trade association for check cashing operations, announced the roll-out of a “revolutionary”, “All Access” Savings Program, which promises to provide “underserved Americans greater access to mainstream financial services” by giving check cashing customers the ability to make electronic deposits in federally insured, interest bearing, savings accounts.

7-Eleven and Wal-Mart In On The New Trend

While a few industry watchers I talked to in New York see these developments as more or less isolated events, Jennifer Tescher, the Director of the Chicago-based Center for Financial Services Innovation, views them as part of a certifiable industry trend and realignment. She insists that “the entire financial services industry is dramatically changing in ways that weren’t even possible five years ago”.

Tescher points to the rise of the non-bank sector in financial services as an indicator of how segmentations within the financial services universe are dissolving. In 2003 the nation’s largest convenience store chain, 7-Eleven, using their own “virtual commerce” technology, placed kiosks in a thousand of its convenience stores machinesthat enabled customers to conduct ATM transactions, cash checks to the penny, purchase money orders, send wire transfers and pay bills.

A year later Wal-Mart raised the bar. Wal-Mart offers check cashing, money orders and wire transfers while also providing banking services in “Wal-Mart Money Centers”. Some analysts believe Wal-Mart, which targets low-income customers and is the world’s biggest retailer, is trying to create a physical and psychological, environment for the customer in which banking, alternative financial services and shopping are collapsed into a single retail experience.

A Gold Rush In Low-Income Financial Services

The sudden “discovery” of the low-income financial services niche by retailers and mainstream bankers is propelled by the explosion in the alternative financial services industry. The lure of this market comes at a time when banks are finding intensified competition in middle class, suburban markets. Meanwhile, branch presence in low income areas has been steadily declining over the last thirty years. One quarter of Black and Latino families, as well as 25 percent of all American families making less than $20,000 per year, don’t have bank accounts.

The very idea of a “fringe” economy is somewhat misleading. About a quarter of the nation’s gross domestic product reflects unreported income and a study conducted by Social Compact, which promotes business investment in inner city communities, estimates that Harlem, a poster child for fringe financial services, has a $1 billion cash economy. And as low income families look for ways to move cash around, check cashers are there to serve them. The alternative financial services industry is racking up an estimated $200 billion in transactions annually.

Of course alternative financial services are widely viewed as exploitative of poor people, particularly in states where there is a lack of regulatory restraint. Customers have very little opportunity to save and build assets using alternative financial services, and whereas banks have some semblance of a mandate to give back to communities where they do business because of the Community Reinvestment Act, check cashing operations have no such obligation.

But in the end, financial service centers are so compelling to their customers because they provide convenience and a wide range of options, with few questions asked: Money orders function as checking accounts. Where banks place holds on checks, check cashing offers immediate liquidity. Pre-paid debit cards, otherwise known as stored value cards, can facilitate everything from long distance phone calling and credit card purchases, to bill paying and, now, even limited-service savings accounts. The fact that check cashers charge, some say, unreasonable fees, is in a way no different that what low-income people expect from a bank or any other kind of capitalist institution doing business in the â€hood.

The Filene Research Institute, which studies issues affecting the future of credit unions, believes so much in the future of alternative financial services that it has created a program that counsels credit unions on how to offer check cashing products. Citing what they see as the declining relevance of credit unions, thrifts and banks in certain areas, Filene issues a stern warning to depositories of all stripes: Begin adopting the ways of the check casher or perish.

Some banks have clearly seen the writing on the wall.

Union Bank of California (UBC) owns and operates over 50 hybrid financial service outlets, in which check cashing services are offered in banks and stores, and banking services are offered in check cashing locations.

KeyBank, just one of many enthusiastic UBC disciples across the country, has created “KeyBank Plus”, a separate product (and teller) line designed especially for low-income customers without bank accounts. Officials from KeyBank maintain that, once a customer enters a Plus branch, Key creates conditions that will prompt that customer to establish a long term - and higher profit margin – relationship.

“The banking industry has done an amazing job of sending messages of exclusion through its product design and minimum balances.” says Edna Sawady, chief operating officer for community development at KeyBank. “At banks many customers fear that they won’t qualify for something…In check cashing lines you don’t run the risk of being rejected”.

Rising Challenges and Criticisms

Regulatory agencies will be challenged to catch up to, much less stay ahead of, these changes because the fundamental elements that help us make distinctions between financial services industries -- the deposit, the check, the branch, credit -- are themselves moving, morphing targets.

Pre-paid debit cards, for example, are exploding in popularity and operate in a virtually unregulated environment. As pre-paid debit cards are used to perform traditional banking functions, like checking, what classifications and regulatory jurisdictions will be applied to monitor and standardize their use?

Financial service entrepreneur Joe Coleman of RiteCheck, a co-engineer of the RiteCheck/Bethex collaboration, is leery of banks encroaching on his territory. He thinks RiteCheck and credit unions like Bethex, whose products are designed for low-income people, have a future together because “we have the same customers”

New York poses its own particular restrictions for check cashers. One notorious service that is popular throughout the country, pay day lending, a type of short term, very high interest loan, is illegal in New York. More importantly New York requires that licensed financial service centers cannot operate within 3/10 of a mile from one another and cannot charge a check cashing fee exceeding 1.5 percent of the check’s face value.

But ultimately, it is the low profit margin on fringe financial services (Coleman calls it “1 million people with a dollar”) that is most daunting to institutions who don’t measure success by the number of live bodies in their lobby. Even Joy Cousminer, president of Bethex and Joe Coleman’s collaborator, acknowledges this tension. “Check cashers lose less money on a bad check than on a slow line. With us, it’s exactly the opposite.”

Cousminer also doubts that banks are actually interested in building relationships with poor people and believes banks are in fact keeping their check cashing and banking customers distinct and separate.

Whether banks using integrated bank-check cashing services are making money on the check cashing side, or through the “migration” of customers to the bank side, or both, is unclear. At least one of the bank representatives I spoke to refused to disclose that information. What is clear is if Checkspring, or any other New York bank, faithfully follows the UBC and KeyBank strategy, and doesn’t mind masses of poor people in its lobby, it stands a fighting chance of turning a profit after a few years. UBC has been at it for thirteen years and Keybank is preparing to expand its program dramatically. Once one bank pulls it off in New York, others might follow.

Not everyone thinks this a good thing. Sarah Ludwig, executive director of the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Projectfears that banks will, in trying to turn a profit, give shorter shrift to the goal of building a bridge between the underserved and asset-building opportunities. “We’ve got this massive problem of low-income people needing essential financial services,” says Ludwig, “but now banks are starting to provide services that not comparable to the services that are provided” in middle class areas.

For Ludwig, and many other advocates who are highly critical of the check cashing industry, alternative financial services are a symptom of the problem, not a solution. “The fringe products that banks offer will look cleaner and meet regulatory standards, but the bottom line is they are still inferior products…There is an unequal, two-tiered financial services industry…We shouldn’t try to serve the low-income market in a way that perpetuates this segmentation.”

Coleman shrugs off this criticism. “In banks there is a middle class prejudice. They want to sign you up. They think everybody wants to be like them...I know we are helping people. We are helping them build their lives.”

Mark Winston Griffith, a founder of the non-profit Central Brooklyn Partnership and a fellow at the Drum Major Institute for Public Policy, has been in charge of the community development topic page since its inception in 2003.Â

Restoration on Eldridge Street

|

Forty years ago, New York reacted to the loss of old Pennsylvania Station by passing a law to protect city landmarks. In this series, in partnership with Open House New York, New Yorkers with a stake in the physical city will argue the consequences of the law, the merits and drawbacks of the preservation movement, and what the future might bring. |

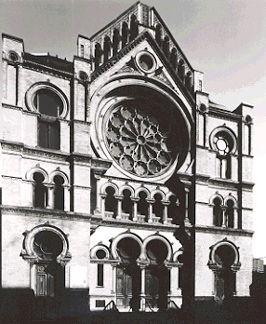

When Gerard Wolfe, then a professor at New York University, first entered the main sanctuary of the Eldridge Street synagogue in the mid 1970s, he found a time capsule. The 19th century Lower East Side building still served as a synagogue but, over the years, as the size of the congregation dwindled, the worshippers had moved downstairs and shuttered the doors to the main area.

Wolfe, who was writing a book about the synagogues of the Lower East Side, discovered a space both spectral and spectacular. Cobwebs extended between the building’s hand-painted pillars. Old prayer books were scattered among the pews. Decades-old prayer shawls remained hidden in special compartments of the benches intended for the tallisim. Newspapers, from the 1940s, opened to the sports pages, lay on seats, a clear reminder of the people who attended services and would perhaps sneak a look during the rabbi’s sermon.

And yet the grandeur of the sanctuary remained intact. The sanctuary’s exquisite (if deteriorated) stained-glass windows, hand-painted murals, and Victorian fixtures signaling the importance of the structure for its Jewish immigrant founders.

And yet the grandeur of the sanctuary remained intact. The sanctuary’s exquisite (if deteriorated) stained-glass windows, hand-painted murals, and Victorian fixtures signaling the importance of the structure for its Jewish immigrant founders.

Wolfe’s discovery marked the beginning of a restoration project, still going on 30 years later, that serves as a model for other historical houses of worship in New York City and throughout the country.

SYNAGOGUE AND STATE

Under the leadership of leading preservationists and community activists, including Roberta Brandes Gratz, an urban critic and journalist, the Eldridge Street Project was founded. This group wanted to save the building. They also wanted to open this historic treasure to the public in the immediate community and beyond.

They faced daunting challenges. Unlike many other historic sites around the city, the synagogue was not about to be torn down and had not been vandalized. But it was in danger of falling down. The roof leaked, threatening the interior. The cellar had filled in, and a stair tower collapsed.

The city of New York does not give money to houses of worship for fear of violating the constitutional restrictions on state aid to religious institutions. Some foundations are also reluctant to aid religious groups. And so, it was very important to establish an educational and cultural center serving a diverse constituency. Today, the congregation -- officially called Congregation K’hal Adath Jeshurun with Anshe Lubz -- owns the building. The congregation is several dozen strong, a stalwart group committed to the continued spiritual life of the building.

The city of New York does not give money to houses of worship for fear of violating the constitutional restrictions on state aid to religious institutions. Some foundations are also reluctant to aid religious groups. And so, it was very important to establish an educational and cultural center serving a diverse constituency. Today, the congregation -- officially called Congregation K’hal Adath Jeshurun with Anshe Lubz -- owns the building. The congregation is several dozen strong, a stalwart group committed to the continued spiritual life of the building.

The restoration is the responsibility of the Eldridge Street Project, the non-profit non-sectarian group formed in 1986. Under a memorandum of understanding, the congregation controls all the religious aspects of the synagogue, while the project oversees the restoration – included related fundraising – and the cultural life of the building. The project runs educational and cultural programs, as well as tours, for some 20,000 visitors a year.

Whenever a church or synagogue asks us for advice about how to restore their site, we tell them the first step is to create a separate 501-C3 (tax exempt) organization to make a clear distinction between the religious life of the building and the historical or educational functions. While few, if any, groups are identical to us, some are similar. The Cathedral of St. John the Divine is one. In some parts of the country, particularly the South, where the Jewish community is fast disappearing, not-for-profit organizations have taken over synagogues and restored them as museums or for other projects. In these cases, though, there is no congregation anymore.

In recognition of our public service, the city provided first program support and more recently capital support for the restoration of our landmark building. There was little resistance to public money coming to us. Norman Siegel, then executive director of New York Civil Liberties Union, called the funding “constitutionally suspect,” but that was about it. The city funds served as a rallying point for us to get other support.

The city was largely responsible for the most recent phase in our restoration -- the creation of a new cellar. Much of the area was filled with dirt, so workers had to excavate it while, at the same time, supporting the building -- an engineering feat. The city money, matched by private donations, was particularly welcome because private donors often do not want to pay for plumbing or mechanical systems. Now we can turn our attention to the most beautiful aesthetic parts of the restoration.

Another interesting example of the sensitivity of a sacred site receiving public funds arose in connection with funds received from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Commission rules bar it from supporting a capital project that includes religious iconography. Several years ago, we approached them for funding for our roof project. This turned out to be tricky as the finials mounting the roof feature elegant Stars of David. Eventually, we found a clear stretch of work without the stars and received a $25,000 grant from the commission.

Another interesting example of the sensitivity of a sacred site receiving public funds arose in connection with funds received from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Commission rules bar it from supporting a capital project that includes religious iconography. Several years ago, we approached them for funding for our roof project. This turned out to be tricky as the finials mounting the roof feature elegant Stars of David. Eventually, we found a clear stretch of work without the stars and received a $25,000 grant from the commission.

Being designated a city and national landmark has also propelled us forward The city landmark recognizes the architecture, while the National Historic Landmark designation is both about the architecture and the building’s significance as being representative of immigrant religious structures. Receiving national designation is a real challenge, as you must explain in detail why your site is either the only one of its kind or a platonic ideal of a phenomenon. Much of our fundraising has been through national direct-mail appeals – many to people who have a tie to the neighborhood or see this site as a kind of portal to their ancestors’ Jewish experience. To these people, designation as a National Historic Landmark has been very meaningful. It serves as a kind of vetting.

A LOWER EAST SIDE STORY

Certainly, this building has been enormously significant both in this neighborhood and to the East European Jewish experience in America. In 1886, when construction began on the building, most synagogues on the Lower East Side were shtetla, small storefront synagogues for people from a single city. But Eldridge Street was unique -- a cosmopolitan congregation of people from all over Eastern Europe.

It was the first grand structure in the neighborhood, taking 10 months and about $100,000 to build. The members constructed a building that dominated the block. This was the first time they could worship openly as Jews so they put Stars of David on the façade. And because many of them worked in factories and lived in dark tenements, they placed windows on every side of the building to beautifully illuminate their synagogue.

Some of the Eldridge Street synagogue founders had been in America for a while already. They had arrived in the 1850s -- before the major wave of East European Jewish immigration in the 1880s and 1890s – and had established themselves.

As many as 1,000 families belonged. They ranged from very wealthy members to people who could not afford the dues. We know from minute books that some people paid $2 for their seat, and some paid $200. It is and was an Orthodox house of worship so the men and the women sit separately.

As many as 1,000 families belonged. They ranged from very wealthy members to people who could not afford the dues. We know from minute books that some people paid $2 for their seat, and some paid $200. It is and was an Orthodox house of worship so the men and the women sit separately.

Until the 1920s, this was a very vibrant congregation. Then, the immigration laws changed, so the immigrants stopped arriving. At the same time, everyone who lived on the Lower East Side wanted to get out. The Jews left for the Bronx, Brooklyn and even the Upper East Side. With no new Jewish immigrants arriving to replace them, this and other congregations got smaller and smaller.

Some of our visitors are disappointed the area is not still Jewish. But this is a story of immigrant success. The East European Jews wanted to leave the neighborhood, and they were able to.

REDISCOVERING THE SYNAGOGUE

Despite the changes, a congregation always remained at Eldridge Street. But it could not maintain the building’s grand main sanctuary and so, at some point, probably in the 1950s, the members closed the doors and stopped coming upstairs to the main synagogue.

Today, the building boasts a new slate roof. The cellar has been dug out. Air conditioning and ventilation systems have been installed, while the crumbling stair tower, now rebuilt, will house an elevator. But the synagogue’s striking architectural details, including rose windows, 70-foot ceilings and a velvet-lined ark, remain. So far, the project has raised about $8 million of the estimated $12 million need for the renovation. At time progress has been slow-going, but the restoration is currently moving ahead, and we anticipate completion by early 2007.

And the building is once again open. Children, adults, and families come to learn about Jewish history, the immigration experience and architecture and historic preservation. They represent all cultural backgrounds (For a schedule of tours, click here)

BOTH EGG ROLLS AND EGG CREAMS

Many people visit because of nostalgia or because the Lower East Side was the gateway place for their families. Others come to see the space and learn about the American immigrant experience, particularly the East European Jewish experience.

Many people visit because of nostalgia or because the Lower East Side was the gateway place for their families. Others come to see the space and learn about the American immigrant experience, particularly the East European Jewish experience.

Amid all the educational programs the Eldridge Street Project offers – some focusing on architecture, others on the East European Jews in the United States – we also work to reach out to the synagogue’s neighbors, many of whom are first generation Chinese immigrants. The Eldridge Street Project’s relationship with these residents testifies to the continuing immigrant experience in New York.

A few weeks ago, our annual egg roll and egg cream festival showcased the two communities – Chinese and East European Jewish -- that have lived or live today on this block. More than 1,500 people joined us for klezmer music, Chinese opera, and Jewish and Chinese folk music performances; Hebrew and Chinese scribal art, Yiddish and Chinese games, and, of course, kosher egg creams and egg rolls.

Last year, we presented a video installation featuring a 12-minute film projected at night through the synagogue windows. It included a 12-minute history of the synagogue and its neighborhood and images that explained what is happening today.

Eldridge Street encapsulates a piece of our history that is important to preserve. It is an architectural landmark, a place of historic importance in the city, a beautiful place. But, as the festival and the video project have demonstrated, what is even more amazing about the building is the new life it has taken on as a place where people can come together and learn about the past.

Amy Milford is director of public and community relations for the Eldridge Street Project.Â

NASCAR, The Largest Proposed NYC Sports Stadium Of All

Despite all the press about proposed new sports stadiums, many New Yorkers know surprisingly little about the largest one. Which one would have the biggest field, the most spectator seats, feature the biggest new retail mall, and sit on the largest redevelopment site?

Not the West Side Stadium, even if it hadn’t gone down to defeat through a mix of community organizing, Cablevision cash, and political pique. Not the Nets Arena at Forest City Ratner’s proposed Brooklyn Atlantic Yards (which received something of coronation recently from The New York Times, as if to reassure the public that this is still a developer’s town), even though the project’s 21 acres could wind up having as many as 6,000 units of housing and 200,000 square feet of retail space. Not the new Yankee Stadium, with its new lucrative luxury sky boxes, to be built on the site of Macombs Dam Park in the South Bronx.

The largest sports facility proposed for NYC right now is a NASCAR track on Staten Island. The track would seat 80,000 fans, watching cars race around a track three-quarters of a mile long, near a new 620,000 square foot big-box retail mall on a 675-acre site. The site, the former BATX oil tank farm located off the West Shore Expressway, south of the Goethals Bridge in Bloomfield, S.I., is the largest vacant industrial property in New York City (and the site of a gas tank explosion in 1973 that killed 40 workers).

Who Among Us Does Not Love NASCAR?

Blue-state, subway-riding New Yorkers -- who don’t feel the pressure that John Kerry did to be loved by American stock-car racing fans -- might be forgiven for knowing little about the fastest growing sport in the United States. NASCAR – the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing -- was founded in 1948 by Bill France, Sr. Several years later, he founded the International Speedway Corporation, which owns the racetracks. Stock car racing remained a largely Southern sport, with a limited audience, until the 1970s, when the R.J. Reynolds tobacco company became a lead sponsor, and the Daytona 500 became the first nationally televised stock car race. Still a family-owned business, NASCAR has annual revenues in the billions and is regularly cited as the fastest growing spectator sport in the United States.

The International Speedway Corporation, also owned by the France family, owns 12 of the NASCAR racetracks around the country (they recently opened tracks near Kansas City and Chicago). The ISC has been actively looking to expand into the northeast for a while. After deciding that an available site in the Meadowlands was too small, they set their sites on Staten Island. In December, the ISC and the Related Corporation (one of NYC’s largest real estate developers, whose recent projects include the AOL Time Warner Center and the Gateway Center mall in East New York) teamed up to buy the property for $110 million.

Traffic, Environmental, and Fiscal Lessons from the Gas Guzzlers

Since purchasing the site, the International Speedway Corporation has been hard at work to pre-empt local concerns about environmental issues and especially traffic. They have put forward an innovative traffic plan for the three races that would take place each year. There will be only 8,400 parking spaces for the 80,000 fans, and Staten Islanders will have priority for these. Everyone else will have to come by ferry (NASCAR says they’ll rent just about every available ferry in the region on race weekends), bus (from parking lots in New Jersey and elsewhere), and perhaps even a new light rail line. And fans shouldn’t count on driving anyway and parking on local streets. Every ticket will be tied to a means of transportation, and you won’t be allowed into the race any other way. NASCAR also promises to pay to widen the Goethals Bridge toll plaza and add new ramps to their site from the West Side Expressway.

In addition, the International Speedway Corporation says they will preserve 245 acres of the site as wetlands (the site features heron and ibises). The new ferry docks on the site could be used by commuters during the work week. Local schools and not-for-profits will be able to use the track on the 300+ days per year when there is not race activity, and they are allowed to solicit in the stands on race weekends.

When lined up against NYC’s other mega-projects, Aaron Naparstek has written, “the Nascar track is in many ways the most innovative, thoughtful and urban-friendly … So, what does it say about the state of New York City urban planning and development that the toothless, beer-bellied rubes of Nascar are doing a better job of caring for our city than we are?”

One other feature distinguishes the NASCAR proposal from the Jets and the Nets: The International Speedway Corporation is seeking no public subsidies for their $550 million track, and it is likely they would even pay some real estate taxes – although it is still possible that the Related Companies will seek subsidies or city money for infrastructure for the mall.

Local Opposition Growing

Despite these innovative features, local sentiment has not been favorable. Last week, 40 Staten Island activists, including ministers and the leaders of civic organizations, gathered to form a united group to oppose NASCAR. They are hoping to form a broader umbrella group of civic organizations opposed to the project.

As a result of growing civic pressure, several elected officials have become more critical of the project. Republican South Shore Councilmember Andrew Lanza was quoted in the New York Times in May, 2004 as saying, “It’s an intriguing idea that we would like to explore further. At first you are concerned about the additional traffic and noise, but then you take a closer look at it, and you are only talking about a couple of events a year and you have a great facility that can be put to other uses.” By this March, however, Lanza said he was gearing up to intensify his opposition to the track. Democratic North Shore Councilmember Michael McMahon mused in December that with community benefits like a new high school and an indoor track & field complex, the project might be made to work for the community. But more recently he has been critical of NASCAR’s traffic assessment. And Republican Mid Island Councilmember James Oddo, who represents the area, has consistently expressed skepticism. Their opinions will matter -- since (also unlike the Jets and Nets) the project is not sponsored by the Empire State Development Corporation and will therefore have to go through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) which includes a vote by the City Council.

Residents and elected officials are concerned that while the track will start with 8,400 parking spaces, the ISC will find it unworkable and try to expand to more. NASCAR fans often come for the entire weekend (a good many in Winnebagos – current plans call for 635 RV parking spaces on site), so how will they get around while they are here? Others are concerned that even if race weekend traffic is managed, the proposed retail mall would cause more consistent problems on the West Shore and Staten Island Expressways, and on the Goethals Bridge.

In addition, because there are only three races per year, the track could be of limited benefit to the local economy. There will be construction jobs, and it will surely be good for Lois and Richard Nicotra, who have recently built a surprisingly successful hotel complex nearby. However, because the traffic plan will prevent people from driving, it is unlikely there will be much spillover to many area businesses. The big box retail stores are likely to be national chains, which won’t help local businesses, and which generally create lower-wage jobs.

But NASCAR suggests that other uses for the site could be even less desirable. The site is contaminated, and will require more than four million cubic feet of silt to raise the ground to a level that won’t be underwater in heavy rains. As a result, it is unclear if it would be appropriate for residential use. Staten Island residents have recently protested against what they see as overdevelopment, so many might frown on new housing there anyway. Some have called for a movie studio, but with the new Steiner Studios in Brooklyn already competing with Silvercup and Kaufman in Queens while the film industry is increasingly leaving the U.S. altogether, it is hard to see how a studio here would compete.

Whether Staten Island and New York City will be willing to go for the ''noise and speed and glory and death'' that is NASCAR (32 drivers have died in crashes) – as described in Jeff MacGregor’s new book, Sunday Money: Speed! Lust! Madness! Death! A Hot Lap Around America with Nascar – remains to be seen. One thing is certain, though. If the track is built, New York politicians running for national office will have less distance to travel to show their solidarity with American race car fans … so long as they don’t forget their ferry ticket.

Brad Lander is the director of the Pratt Institute Center for Community and Environmental Development Â