Preserving Social History on Roosevelt Island

Forty years ago, New York reacted to the loss of old Pennsylvania Station by passing a law to protect city landmarks. In this series, in partnership with Open House New York, New Yorkers with a stake in the physical city will argue the consequences of the law, the merits and drawbacks of the preservation movement, and what the future might bring. |

In April 1975, 2,000 new apartments opened on Roosevelt Island -- a tram ride away from the East Side of Manhattan. And so this April 25 marked the 30th anniversary of the current Roosevelt Island community.

But while many New Yorkers think of Roosevelt Island as a new community, for much of the 19th and early 20th century it played an important role in the life of the city. Much of this history was lost in the 1960s and 1970s, when the city was only beginning to recognize the value of preserving its history – and its old buildings. As attitudes and policies changed – with, for example, the enactment of the Landmarks Law that created the city Landmarks Preservation Commission – a handful of buildings were saved. Now, with the real estate market putting new pressures on the island, it is more vital than ever to preserve the history of this 147-acre piece of land in the East River.

For decades, Roosevelt Island, Blackwells Island, or Welfare Island -- whichever name you want to use -- was home to a penitentiary, workhouse, lunatic asylum, Metropolitan Hospital, City Hospital, and various almshouses. Goldwater Hospital, for victims of polio and other chronic diseases opened in 1939.

And so Roosevelt Island was key to our corrections history, our medical history, our social service history. It is the history of how people were treated and of what people thought.

Over the years, much of this has been forgotten because, as someone once said to me, these were not the golden years. The institutions on Roosevelt Island were not the kinds of places you glow about, but they did provide desperately needed services. In the 1940s, 10,000 people lived on the island, mostly in institutions. We should not forget them.

Designed by James Renwick, the lighthouse at the northern tip of Roosevelt Island helped ships navigate their way through treacherous waters. |

Roosevelt Island is also part of our architectural history. The works of Frederick Clark Withers, James Renwick, and Alexander Jackson Davis -- three very prominent architects -- are still visible on the island.

If the island had been developed 10 or 20 years later, the builders probably would have saved more of the structures. But in the 1960s and 1970s, many beautiful buildings were just bulldozed. The development corporation had the attitude, "when in doubt, throw it out." Their theory was that it is cheaper to build new.

And so we lost the city hospital, a large Versailles-looking building at the southern end of the island. The administration tore it down, in the early 1990s, but it could have been restored into a beautiful chateau-like building.

The Central Nurses Residence, a massive yellow brick dormitory built for nursing students and staff in the 1930s, was a perfectly good building that could have been converted to a different use, but the island administration decided to abandon it, because it interfered with vehicular traffic flow. And some beautiful houses at the northern end of the island could have been rebuilt.

Our landmarks are technically owned by the state of New York, meaning the city has little control over them. The other dilemma is that the government exempts themselves from any penalties and protection of abandoned landmarks. Thus, the Smallpox Hospital, a government building, has never been rescued by a municipal agency.

We are lucky that the developers saved at least the six historic buildings we have today. Without our 40 years of landmark legislation, these structures would almost certainly have vanished as well, But today all are on the National Register of Historic Places and on the state register and are designated New York City landmarks.

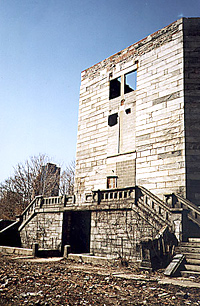

If you start from the southern tip of the island, you see the smallpox hospital designed by James Renwick in the 1860s. Back in the 19th century, this was about the only hospital where rich people went. Usually, poor people went to hospitals and died, while rich people were treated at home. But because smallpox was so communicable, even rich people who contracted it had to go to the hospital.

The Octagon once served as the entrance to the country's first municipal lunatic asylum but will soon link two wings of an apartment building. |

The building later became Riverside Hospital and then a school of nursing -- the third one in the United States -- until it was abandoned in the 1950s. For more than 20 years, the site remained closed to the public.

But some New Yorkers remembered the building, perhaps noticing it lit up at night when they drove along the FDR Drive. And so in 2003, when Open House New York featured it as one of its sites to visit, 400 people came on a single day to this landmark at the island's southern tip. In 2004m more than 700 people again visited the site in two days of Open House New York.

They saw a building in terrible condition. In winter, as water freezes and melts, cornice stones fall from the facade. But the building's grandeur shows through the flaws.

Imaging and computer work indicates that the hospital would need millions of dollars in repairs to stabilize it. No one has come up with an economically feasible plan to restore the building. Most likely, it will become a kind of stabilized ruin.

A kinder fate has befallen Strecker Memorial Laboratory, a charming Withers and Dickson Romanesque structure. Built in the 1890s, this medical research facility sat fallow for almost 50 years. Then the Metropolitan Transportation Authority decided to use the building for a power conversion substation for the train lines that run beneath the island. electricity station. The agency restored the building's exterior and installed equipment inside. It opened five years ago and remains in beautiful condition, an example of how creative thinking can save an old building.

As you go up Main Street, you see Blackwell House, a gray wooden farmhouse built in 1796 by the Blackwell family when they owned the island. In the 1970s, when the island was developed, architect Giorgio Cavaglieri completely restored the building. Unfortunately, the people who ran the island in the 1990s leased Blackwell House to tenants who did not take care of it. Now, we are in the final steps of obtaining the long promised state funds to do repairs and hope to reopen the house as a community building and preserve this building for the future.

The next landmark is the Chapel of the Good Shepherd, an 1889 brick and brownstone chapel designed by Frederick Clarke Withers, who also designed Jefferson Market Courthouse. Originally, the chapel served the residents of the city home or almshouse, which at one time, was home to between 2,000 and 3,000 poor and homeless people. Restored, also by Cavaglieri, in 1975, the church is used by both the Episcopal Church and the Catholic Church. It is also our largest community meeting space.

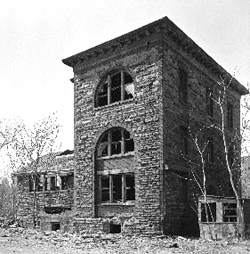

The Octagon offers a more complicated story. Built in the 1840s, it served as the first municipal lunatic asylum in the country until 1895 when it became Metropolitan Hospital. As a young writer, in 1843, Charles Dickens visited the asylum and wrote about the listless, mad people cowering in the hallways. As a reporter for Joseph Pulitzer's New York World, Nellie Bly, whose real name was Elizabeth Cochrane, had herself committed to the asylum for 10 days in 1887. She then wrote a scathing expose on the horrible conditions, which did succeed in improving it a little.

During this period, the Octagon functioned as the entrance to the asylum, with two wings coming off of it, creating an L-shaped building. Now the wings are gone, but the octagonal entrance is being completely restored. Two fairly modern-looking new wings will hold about 500 apartments. They have already added four floors adjacent to the Octagon -- the landmark Octagon. And some people do not see the merit of saving any of it. Recently, I was at the Octagon building and the construction site manager said to me, "Why didn't they just tear that down a few years ago?"

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority saved Strecker Memorial Laboratory when it renovated the 1890s building for as a power conversion substation. |

Putting modern wings on a landmark building is not an ideal solution. But at least a small piece of the original building, including a recreation of the beautiful interior staircase in the dome, remains. The exterior will be an exact copy of the original, since it is a landmark structure.

And in some sense, visiting the Octagon to get a sense of its history resembles going to Rome. When you go to the Coliseum, you don't see lions or people being slaughtered. You have to use your imagination. Sometimes, small fragments make people think about what was in a place and what went on there.

And last but not least we have the lighthouse, also designed by Renwick, which has been repaired and restored. Only 53 feet tall, it was built in 1876 to light the way at the tip of the island because the river's swirling currents are very treacherous.

While we celebrate these buildings, challenges remain. Raising money for the projects is always a problem. And today's real estate market could also affect the island, home now to some 10,000 people. About 1,200 people will move into the new wings of the Octagon. The Southtown development is supposed to include nine buildings. Plans to put affordable housing there now are in doubt. The landlords would like to see resident of 2,000 original affordable apartments lose their subsidy and rent the building at market rates. It has become a gold rush.

If you come to the island on a summer late afternoon or evening, parents and kids are sitting in the park outside the chapel. We have beautiful little cul-de-sacs and little grassy areas. They are empty because people like to be in public spaces. They like to be on the street. Developers and urban planners often do not seem to understand that. And people like our old buildings. They like to sit outside of Blackwell House and the little park next to it. The lighthouse park also is very popular. These landmark structures are somehow more comfortable than the concrete of our 1970s design.

I love Roosevelt Island. It's a small town, people caring about each other, people knowing each other, sitting around and schmoozing. It's almost like the old days. And our six historic buildings contribute to that feeling. They tell us about our past and they add character.

Judith Berdy is president and historian of the Roosevelt Island Historical Society

Zoning Instead of Planning in Williamsburg and Greenpoint

Once again, the city is zoning without a plan.

About five years ago, after hundreds of meetings and more than a decade of work, community groups in the Brooklyn waterfront neighborhoods of Greenpoint and Williamsburg reached consensus on plans to revitalize their decrepit industrial waterfront. The Greenpoint and Willliamsburg 197-A Plans (after Section 197-a of the City Charter that allows communities to submit plans for official approval) proposed a mix of low- to mid-rise housing more or less like the three and four story buildings in the neighborhood, so it would be affordable to tenants in this working class neighborhood. This kind of contextual development became more critical as the neighborhood began to face intense development pressures. The 197-a plans proposed that the mix of industry and housing be brought down to the waterfront, but without the noxious industries like waste transfer stations that have concentrated in the area in recent years. And they wanted public access to the waterfront. The Department of City Planning studied the community plans, made a lot of changes, and then the plans were approved by the City Planning Commission and City Council.

The massive rezoning of Greenpoint and Williamsburg that the City Council just approved bears little resemblance to the community plans. Ever since the City Council voted for the Greenpoint and Williamsburg plans in 2001, they have failed to lift a finger to implement them. City agencies went into hiding. There were no budget requests to create public access on the waterfront, no initiatives to preserve industry, and no new housing. Instead, the city turned the other way as developers illegally converted industrial properties to unaffordable lofts, and did little to stop the legal conversions.

Now the City Planning Commission and City Council have approved a sweeping rezoning of the industrial waterfront that opens the way for 10,000 units of high-rise housing, conversion of industrial properties to residential use, and a 54-acre waterfront park. The final rezoning does have some elements that meet plan objectives, but they are in there because community activists fought a long, hard battle with the city from the first day the proposal was launched to get some affordable housing, lower the towers on the waterfront, protect industries, and guarantee public access to the waterfront.

But community activists aren’t uncorking the champagne. The distance between the rezoning and the community plans is still gaping. Brooklyn’s Community Board One and the Brooklyn Borough President voted against the rezoning, and Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum opposed it. In the end, the city made a few concessions that help relieve the pain: thirteen mostly industrial blocks were taken out of the rezoning to protect the industries, five more acres of park were thrown in, and future developers got more incentives to create affordable housing units. But while the end result may be applauded by Manhattan Mike Bloomberg, it’s left many disappointed souls on the other side of the East River.

Rezoning Without A Plan

The Greenpoint-Williamsburg rezoning follows the city’s well-established policy of using zoning instead of planning to govern land use policy. In many cities and towns across the country, it’s just the opposite. The legal basis for zoning is usually some kind of reasonable plan: government develops a plan and shapes the zoning to fit the plan. This is elementary land use planning. In New York City, ever since the City Planning Commission refused to approve the city’s first and only master plan in 1970, planning itself has become an idle pastime -- at both city-wide and neighborhood levels. The bulk of the officially-sanctioned (197-a) plans, and scores of other community plans, have been produced by community planners with little help from the city. To the extent that the city produces plans at all, they are usually studies aimed at justifying zoning changes, not comprehensive proposals that look at all city policies that affect the economic and social livelihood of communities.

Mixed Use and Industry

According to Mayor Bloomberg, the rezoning “protects the fabric of inland neighborhoods, preserving their mixed-use character, preventing noxious, heavy industrial uses and further out-of-scale development.” This is done mostly by establishing mixed-use zones where housing and industries can coexist. The problem is that the city’s “MX” zones are set up in a way that individual landowners make the decision about whether housing or industry will prevail. Now, if you owned a plot of land in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood like Williamsburg and you have a choice of getting rent from residential tenants that is five times the amount you could get from industrial tenants, which way would you go? The end result of this “mixed use” zoning will be de facto conversion of viable industrial properties for use as housing. The MX zones in Greenpoint-Williamsburg actually replace the Northside Special Mixed Use District and Franklin Special Mixed Use District, which did a pretty good job since the 1970s of stabilizing this classical mixed-use neighborhood because they limited the options of residential developers.

While the city eventually removed 13 industrial blocks from the rezoning, according to Adam Friedman, director of the New York Industrial Retention Network, “these 13 blocks were pretty important but there are around 40 blocks that have significant job clusters.” Friedman praised the creation by the city of a $20 million fund to support non-profit business creation (which he attributes to the work of City Council members David Yassky and Diane Reyna, with the help of Speaker Gifford Miller), and the establishment of a 22-block Industrial Business Zone. However, he feels that there should have been “a more balanced mixed use policy.”

These concessions, while important, are probably not going to be enough to stem the decline of industrial jobs prompted by real estate speculation. One of the great advantages for small industries in this neighborhood is the linkages they form with each other because of their proximity. The rezoning will balkanize industry into shrinking enclaves. And since over 80 percent of local industries hire local residents, they will now have more trouble finding local help among the tide of yuppies. While the mayor touts “the creation of 11,000 construction jobs and over 600 permanent jobs over the next 10 years,” the construction jobs are obviously short-term and tend to benefit disproportionately skilled workers living outside the city. In fact, it has now become a common scene to watch the hard hats demonstrate at the mayor’s mega-project ceremonies before they get in their SUVs and drive home to the suburbs.

Finally, in a tacit admission that they didn’t plan before rezoning, the City Planning Department now agrees they will go back and study the industrial areas in the neighborhood to see how zoning can help them! Also on the list of things the city agrees to do is to help relocate businesses to the Brooklyn Navy Yard enclave -- not an encouraging note for the community that wants to maintain its mix of industry and housing.

Affordable Housing

Community coalitions fought the rezoning hard with the goal of mandating that 40 percent of all new housing units be affordable to low- and moderate-income households. What they got was a voluntary program driven by bonuses to developers that might make one-third of all units affordable. While this is better than the 23 percent the city originally proposed, to become a reality it all depends on a number of future events that may not happen. Meanwhile, the small group of waterfront landowners, and the much larger group of upland owners, are free to go ahead with development plans and tenants in the neighborhood will continue to face daily pressures to move.

“While we’re celebrating certain victories,” says Cathy Herman, director of Planning and Development for Los Sures, a local non-profit community development corporation, “we’re not completely content. Further market-rate development is a threat to the local low-income population.”

The new affordable housing depends entirely on whether or not developers will take advantage of the zoning incentives to build. Since the high density (R8) residential zoning that now goes into effect will give developers enough floor area to build profitable high-rise market-rate condos with precious waterfront views of the Manhattan skyline, there is good reason to doubt that much affordable housing will get built. Voluntary inclusionary zoning incentives have been in effect for decades in parts of Manhattan and have produced very few affordable units. Overlooked were proposals by the North Brooklyn Alliance, a coalition of some 40 groups, to make the affordability requirement mandatory, as it is in hundreds of other municipalities where it’s been successful. And no one in government ever raised the most fundamental question: Since the most dire housing need is among working people with modest incomes who make up the majority of Brooklyn households, shouldn’t the city’s goal be that the majority of the new units be affordable?

Over a third of the affordable units projected by the city would be on sites owned or controlled by the city and non-profit institutions. But these could be built without rezoning the rest of the neighborhood. While a few private owners of waterfront property make the big bucks, the public sector still takes up a big part of the burden.

There are some clear victories, however, for community advocates. The city lowered the base as-of-right floor area ratio (FAR) from 4.3 to 3.7; this means that developers won’t be able to build as much unless they take advantage of the inclusionary provisions. The city administration promised to support legislation in Albany that would make tax incentives available to local developers only if they provide affordable housing.

In yet another tacit admission that they didn’t do the job right the first time, the city now says it will go back and study how they can use contextual zoning to protect some residential areas. They also say they will now rezone the gigantic Domino Sugar Property (located on the Williamsburg waterfront). If they did planning in the first place, they wouldn’t have to keep zoning things piecemeal.

Perhaps the most blatant admission that the city is playing its usual catch-up game with development is the administration’s promise to monitor the needs for community facilities and services only after 25 percent of the expected development has already occurred. In other words, they don’t plan so the services are in place when people need them.

Waterfront Access and Open Space

The rezoning includes a Waterfront Access Plan that mandates public access along the water’s edge. In New York City, developers are only required to provide waterfront access in residential and commercial zones, not industrial zones, an unfortunate policy that only gives policy makers more of an incentive to push industry out.

In Greenpoint-Williamsburg, where 30 or 40-story towers will be going up along the waterfront, the problem is that the new housing will create a wall between the waterfront and the three or four-story walkups that dominate on the interior blocks.

The city believes that turning the required waterfront esplanade over to Parks Department’s jurisdiction will help prevent this privatization from occurring. But even though Parks maintains the space, it can still function more as a back yard for luxury high rises than an amenity available to the whole neighborhood. And many developers will be just delighted to have the city pick up the tab for liability, even though they will have to contribute to a fund to pay for the maintenance.

The Future Without A Plan

In sum, in exchange for a zoning bonanza that developers can cash in on now, the city is giving vague promises, not real plans with teeth in them, to Greenpoint-Williamsburg businesses and residents. A hand-picked Community Advisory Board involving city agencies and some community representatives is supposed to monitor progress. The city will go back to do more studies and more rezoning. The administration is committed to putting money in future budgets. But we’re now in an election year and term limits guarantees a new cast of characters after another four years. Ten years from now, with a whole new administration and City Council, and no legally binding mandates, will anyone remember the fine rhetoric, capital budget commitments, and pledges of concern? The fate of public waterfront access, affordable housing and industrial retention in Brooklyn may wither as all the local diners become espresso bars.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.Â

Pushing For A Rent Freeze

Recently, Mayor Michael Bloomberg told the New York Times that housing issues were now a priority for his administration. The issue, he said, was crowded out of the top of the list when he first took office because the city was facing a huge budget deficit and reeling from the terrorist attacks of September 11.

The cost of housing and homelessness are linked and the mayor’s new sense of urgency was reflected in a flurry of recent announcements on housing. In about a week’s span in April he announced a pledge, with City Comptroller William Thompson, to put $130 million of Battery Park City Authority revenues in a trust fund for affordable housing and announced plans to spend $472 million on supportive housing, $27 million on a renovation and rehabilitation project in the Bronx, and two initiatives to redevelop land in Brooklyn.

With all the focus on housing issues, however, he somehow missed one that is making headlines in all of the newspapers: The Rent Guidelines Board, which is deliberating on whether and how much to raise rents on close to a million apartments in the city. Advocates see it as a curious omission.

“The mayor has to take a position on this,” said Michael McKee of Tenants and Neighbors. “How long can he fail to utter the words â€rent stabilization’?”

At a press briefing after the board held its first vote on a rent increase – setting a range for increases on one- and two-year leases – the mayor again sought to distance himself from the board’s deliberations, staking out middle ground between tenants and landlords.

“Any raises will obviously be too much for tenants,” Bloomberg said. “Any raises will obviously be too little for landlords.”

The board voted 5-4 on the ranges: 2 to 4.5 percent increases for one-year leases and 4 to 7 percent on two-year leases. But it was the preliminary vote. Now, tenants will try to convince the public members to vote for lower rents and landlords will try to convince them to go for higher rents.

“It has nothing to do with the numbers and anybody who thinks it does, does not understand the Rent Guidelines Board,” McKee said. “It’s all about politics.”

McKee was referring to the board staff’s reportsthat reported increases in landlords’ costs at about six percent. While landlords’ costs have gone up, though, the economic situation for most New Yorkers has not markedly improved and, in fact, for many it has gotten worse. More people are spending more of their income on rent, real wages have fallen, homelessness is at record highs, and the number of people on public assistance has increased for the first time since 1993.

The mayor could and should act to prevent another increase in rents, advocates said, because of the affordability problems New Yorkers are facing. At a mayoral candidates’ forum in April, all of his Democratic opponents said they supported a rent freeze.

But Bloomberg apparently is not openly going to pressure the board.

“Well I didn’t tell them how to vote,” he said at the press briefing.

Marvin Markus, the chairman of the Rent Guidelines Board, said he did, however, consult with City Hall on the board’s deliberations.

“They’re interested in the economic impact,” Markus said after the preliminary vote. “I talk to them. I don’t talk directly to the mayor, but I talk to his people, yes.”

The board’s deliberations were considerably more heated than last year –- one man was arrested at the meeting for the preliminary vote and the start of the meeting itself was delayed for 30 minutes by frenzied protests. And tenant advocates are convinced that after more than three decades of rent increases, a rent freeze is a real possibility, even after the 5-4 vote for the range of increases.

“Additional public members have started to understand that affordability is an issue,” McKee said. But, he said, tenants have to make their voices heard at the board’s hearings in June before its final vote on June 21 to achieve a rent freeze.

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations.