Rent Regulation

To hear the most adamant landlords and their supporters tell it, rent control has just about destroyed New York

City, denying real estate developers the opportunity to build affordable housing for a reasonable profit.

To hear the most adamant landlords and their supporters tell it, rent control has just about destroyed New York

City, denying real estate developers the opportunity to build affordable housing for a reasonable profit.

Tenants and their advocates believe just the opposite, that rent regulation has saved the city. It has enabled New York to remain a magnet for the young and the gifted and the hopeful, and protected the average New Yorker from the greed of the real estate industry.

The two sides have been making the same arguments for several generations, in a conflict that has seen many battles. Some New Yorkers wonder if one side has already won. How can anyone say that rents are regulated now, when an apartment can triple in rent when it becomes vacant, and a crummy one-bedroom apartment in Manhattan can go for $2,400 a month?

On the other hand, many New Yorkers who live in rent-regulated apartments — and rent regulation still covers slightly more than a million apartments in New York City, or about half of the city's total number of rental apartments — cannot seem to believe that all regulations might actually come to an end.

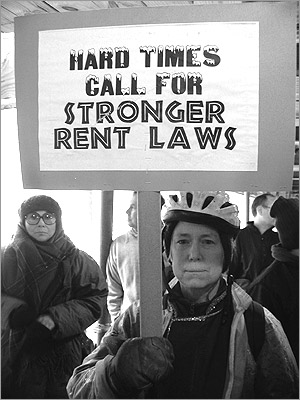

But that threat is real, tenant advocates say — Republicans in the New York State Legislature tried to abolish it six years ago — and, with the current rent regulations set to expire in June, they have mobilized their forces to preserve and strengthen the laws. (See related story.)

A CITY OF RENTERS

New Yorkers have a uniquely proprietary attitude toward their apartments. Elsewhere in the country, middle class people buy big houses with lawns. New Yorkers hope for a sunny window to rent. Other Americans live in apartments until they settle down and acquire a spouse, a kid, a dog — and a house. Many New Yorkers do their settling in their apartments; some two-thirds of New Yorkers are renters.

At the same time, housing costs are notoriously high here. The average New Yorker currently spends almost 30 percent of income on rent, including gas and electricity. More than a quarter (27 percent) of renters spend half or more of their income on rent, according to a 1999 census housing and vacancy survey.

It is not surprising, then, that rent regulation remains one of the hottest issues in New York, with people on both sides holding fiercely to their positions. Landlords and advocates of a freer market for housing say rent controls reduce tax rolls and discourage new construction.

"With 1.1 million rent-regulated apartments, the city is a showcase for the distorting effects of controls," wrote Peter Salins of the Manhattan Institute. He cited "a minuscule vacancy rate, middle-class families trapped in apartments too small for their needs, wealthy retirees paying a pittance for three bedrooms and virtually no new construction to relieve the strain and to upgrade the housing stock."

Tenants counter that rent control was instituted to protect renters from being exploited. "The rent laws were enacted to eliminate unfair bargaining advantages that landlords have over all consumers who are forced to shop for apartments in an overheated market," wrote Timothy Collins, a former executive director and counsel for the city Rent Guidelines Board. "The law was designed to ensure that a landlord could not charge $1,200 for an apartment that — in a normal market — would rent for only $800."

Collins and other tenant advocates say the drive to loosen rent regulation or to do away with it springs more from the political power of the real estate industry than from the merits of a free market argument.

A LONG HISTORY

While rent regulation may have particular immediacy in crowded, expensive 21st century Manhattan, people have sought to regulate the housing market for centuries. The movement gained momentum in the early 1900s. "Because housing markets, like labor markets, are often anarchic and unstable, the trend throughout the century, learned through bitter experience, has been to subject them to government regulation and intervention in order to try to assure some degree of public peace and justice," Ron Lawson wrote in his book, "The Tenant Movement in New York City, 1904-1984."

Faced with a housing shortage and high rents after World War I, the state legislature enacted laws allowing tenants to legally challenge "unjust, unreasonable and oppressive" rent hikes. These laws stayed on the books until 1928.

In 1943, the federal government's World War II Office of Price Administration largely froze rents in New York City. Tenants organized to preserve the protections after the war, and in 1947 New York established a state rent regulation system controlling rents on all residential buildings constructed before 1947. Today, only about 60,000 apartments remain under that old rent-control law.

In the face of rising rents in 1969, New York City enacted rent stabilization, which extended regulations to buildings with six or more units constructed after 1947. This system today covers at least a million apartments. (One result is a confusion over terminology. Some people refer to "rent control" to mean both the earlier rent control system and the later rent stabilization. Others insist that it is important, and more accurate, to make a distinction between the two, and when talking of both of them together, to say "rent regulation.")

Both rent control and rent stabilization officially exist in response to a housing shortage, and would terminate if the number of vacant apartments in New York City ever rose above five percent of the total housing in the city, which has never happened, according to the official survey.

Concern about housing abandonment, a growing problem at the time, prompted the city to weaken rent regulation in 1971, permitting larger rent hikes. The state legislature also instituted so-called vacancy decontrol, which removed vacant apartments from rent regulation.

Rent regulations for all apartments thus seemed doomed. Tenants and their supporters contended that the changes sent rents skyrocketing and were driving people out of the city. In response, the legislature ended vacancy decontrol in 1974.

Observers differ over how much effect the regulations actually have on rents. Barbara Elstein Katz, a retired analyst with the Department of Housing, Preservation and Development, has calculated on behalf of the New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition that the median monthly amount that tenants pay to landlords for rent-regulated apartments in the city is $640, while for unregulated it is $1,090 — 70 percent more.

Landlord advocates say this is not true, that there is less than a $150 difference. According to Dan Margulies, executive director of Community Housing Improvement Program (CHIP), a trade association for apartment building owners, the median unregulated rent in 2002 was around $850.

The discrepancy is because Marguilies includes the small mom-and-pop buildings (buildings with fewer than six apartments) in his calculation, and Katz does not.

CHANGES IN THE SYSTEM

|

CHALLENGING RENT HIKES Under rent regulations, tenants can appeal to the state Division of Housing and Community Development, claiming that their rent is too high. But such a challenge requires detective work. Vivian Dee, head of the Park West Village Tenants' Association in Manhattan Valley, has become an expert. Last year, for example, she helped two tenants who thought they were being overcharged on rents for their separate apartments. Looking over two canceled checks the landlord had provided as evidence of improvements made to the apartments, Dee noticed something odd. "The date of the check was the same. . . . The amount of the check was the same. The number of the check was the same," she recalled. "I was overjoyed." Dee was delighted because the identical $14,550 checks bolstered the tenants' call for a rent reduction. The owners had claimed that the full amount of the check was for only one apartment. A quick look at other checks revealed that this was not the only time the same check had been used as alleged proof of work for more than one apartment. "It was a mistake," said Santo Golino, a lawyer for the landlords, P.W.V. Acquisition. "I think we've fully explained it satisfactorily" for the state. Golino declined to give that explanation. Park West Village, huge high-rise buildings, between West 97th and 100th Streets, near public housing projects, was built with government help as affordable housing. The tenants' association advises new tenants to check to see if their rents are legal. The new Park West Village tenants have won a number of their cases at the state housing division, but the landlords are appealing most of the decisions. Linda Anderson, a college professor and single parent of a 6-year-old son, had been paying more than half of her net salary for her $2,400-a-month apartment at Park West Village. When she looked into her new apartment's rent history, she discovered, "Lo and behold, to my amazement, the rent had been increased" from $935.95 to $2,400. While the landlord claimed $50,000 in work had been done on the apartment, the cabinets do not align, and the paint and plaster are uneven. In the bathroom, tiles are cracked, and paint has dribbled down onto the tiles. She now pays less than $1,200. Anderson said, "I felt like I had really once tested out the system and challenged it and heard that my voice was heard" |

While rent control survives, the state has whittled away at it over the last decade.

Rent controls are "almost like a drug. We all grew up in that kind of environment," said Joseph Strasburg, president of the Rent Stabilization Association, which represents property owners. "We cannot end it overnight."

But tenants see an effort to phase it out. A law passed in 1993 allowed landlords to add one-fortieth of the costs of any improvement they made to a vacant apartment to the rent charged the next tenant. In 1993 the City Council and in 1994 the State Legislature decontrolled rents on vacant apartments renting at $2,000 a month or more if the new occupants' household income was $250,000 for two consecutive years.

In 1997, the New York State Legislature extended the rent stabilization law for another six years — or at least that is what many New Yorkers believed. From the apartment owners' point of view, the 1997 law fixed a flawed system. From the tenant point of view, it created injustices (pdf file) and threatened the very existence of rent regulation. Republicans such as Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno now are willing to let the current law stand — testimony, some observers say, to just how weak that legislation is.

The 1997 law included vacancy decontrol for so-called luxury apartments, costing $2,000 or more a month, regardless of the new tenants' income. Landlords discovered all they need to decontrol the rent on an apartment is for it to become vacant.

Landlords can immediately increase the rent on a vacant apartment by at least 20 percent—more if the departing tenant had lived in the apartment for more than eight years. The landlord can also add to the monthly rent one-fortieth of the cost of any repairs made to the home.

If the rent was $1,000 when the tenant moved out, "the rent immediately goes to $1,200. The landlord gets that without a lick of work," explained Michael McKee, associate director of New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition.

Then, McKee continued, "The landlord asks himself, 'How much do I have to spend to get the rent up to $2,000?' The answer in this case would be $32,000, because the landlord can add one-fortieth of the costs of improvements to each month's rent — forever."

So, McKee said, the landlord puts in new floors, wiring and other things, and "the apartment is forever de-regulated."

Landlords don't even need to document that they have actually done the work unless a tenant challenges the rental price.

Landlords say these rent hikes are fair. "I don't think landlords generally are responsible for what somebody will pay if they want to live in a particular area," said Margulies of the Community Housing Improvement Program. "I used to live on Upper West Side, and I couldn't afford it so I moved. This is apparently a foreign notion to most New Yorkers: There is no God-given right to live where you want to live."

Owners and tenants dispute how many apartments have been deregulated to vacancy decontrol. Owners say no more than 50,000 or 55,000 units. Tenants say 99,000.

When a building becomes a co-op, rental units in the building are decontrolled as soon as the current tenant leaves.

"We calculated that at the present rate of deregulation, half the universe will be deregulated in seven to nine years," said McKee. "In 10 to 15 years, if we don't get vacancy decontrol repealed, there will be no rent regulations at all. There will be so few [rent-regulated] tenants [that they] will no longer have the political ability to get the laws renewed for another period of time, which is clearly the real estate strategy."

As tenant advocates see it, the 1997 law has resulted in tens of thousands of high-rent tenants living without right of tenure and without even a right to renew their leases. "Taking steps against the landlord for code violations and repairs could result in the anomalous situation of people moving into high-rent apartments and being afraid" to complain, McKee said.

Suspecting that they might be paying illegal overcharges, hundreds of tenants call Tenants & Neighbors, McKee said, but often tenants in de-regulated apartments are not willing to take action. "People say, 'If I file and lose, he won't renew my lease.'"

The 1997 law also requires that tenants seeking to challenge rents do so within four years of the hike. This four-year statute of limitations is "one of the greatest reforms" of the 1997 law, said Strasburg. Otherwise, he said, new owners could be penalized and forced to pay huge amounts in back rent and damages. "We're not talking about sophisticated owners," he said. "We are talking small property, not deep pockets."

Tenants, however, say the four-year limit can reward landlords who commit deliberate fraud.

Despite the 1997 laws, tenants still have the right to challenge rent hikes—and some succeed.

McKee advises new tenants not to question the status of the apartment before they move in. But immediately after that, the tenant should check the apartment's rent history with the borough office of the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal. If the rent skyrocketed but it looks like extensive renovations have not been done on the apartment, the tenant might have grounds for a rent reduction. Tenant organizations say they often need to hire an engineer to estimate the actual costs of the work and to document that claimed improvements were not made.

THE REVISED CODE

Other state actions have further eroded tenant protections. In December 2000, the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal revised the rent Stabilization Code. Advocates for both tenants and owners agree it helps owners.

One of the most widely publicized provisions could allow owners to evict tenants who charge roommates more than a "proportionate share" — usually half the rent. The code, which has many provisions, also lets landlords increase the rent when a tenant moves out, even if the tenant was there for less than a year. Owners can collect a rent surcharge from tenants who installed their own washing machines, dryers or dishwashers. Owners who want to evict a tenant so they can use his or her apartment for their immediate family can now consider in-laws immediate family.

With these changes, "the executive branch, meaning [Governor George] Pataki, turned the state housing division from an incompetent but fair agency to an incompetent pro-landlord agency," said Sam Himmelstein, a lawyer who represents tenants. "I've seen apartments go overnight from $1500 to $10,000. Who's that helping?"

The answer to that question depends on where you stand in the rent battles of New York.

Related Article:

The Battle Over Rent Regulation by Sam Roseme

Midtown West Side Story: A Conversation With Robert Moses

Â

I had a dream the other night that Robert Moses, the city's famous master builder of the Twentieth Century, came back from the dead to visit New York. Yes, the long-reviled Moses who bulldozed neighborhoods and replaced them with expressways and high rises; who built parks and parkways in the suburbs; who re-shaped New York for the car. (See Robert Caro's The Power Broker on the Land Use book list.)

Moses came back when he saw Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plan for "Midtown West," the area of Manhattan once known as Hells Kitchen.

Midtown West would basically bring an end to Hells Kitchen, the historic rough-and-tumble working class neighborhood on the west side of Manhattan. This is the neighborhood where West Side Story took place, where generations of immigrants lived, where tens of thousands of New Yorkers still make their home. It's a neighborhood that's been depleted of its population over the last century, cut up by giant renewal projects like the Jacob Javits Convention Center, the Port Authority Bus Terminal, Lincoln Center, and the access ramps to the Lincoln Tunnel. Decades ago, the northernmost part of Hells Kitchen was renamed "Clinton" in efforts to distinguish it from its notorious past.

The plan includes a stadium to be built over the west side rail yards that would be a keystone in the 2012 Olympics, should New York City win the world competition for that event. It also involves extension of the number 7 subway line. The city would give developers hefty zoning bonuses to encourage high rise development in two core areas. A "mixed use" district would incorporate some of the remaining low- to mid-rise residential, commercial and industrial uses. New office buildings would be allowed in the adjacent garment district, where there are now strict limits on new construction. Running through Midtown West and lining the Hudson River waterfront would be an open space network. The plan for Midtown West is basically the same as the one put out by the City Planning Department almost two years ago, and design principles released by the department last fall.

WALKING WITH ROBERT MOSES

In my dream, Moses was walking the streets of Hells Kitchen - sorry, Midtown West - with me. I don't know where he went after he died in 1981, but I guess they didn't have limos there. (When he was the planning czar of New York City, Moses wouldn't be caught dead walking anywhere.)

Moses told me he came back because he was so happy that Hells Kitchen was finally going to be wiped off the map, just like all the other neighborhoods he got rid of while he engineered the city's massive urban renewal programs.

"What do you like about the mayor's plan?" I asked him.

"Well, first of all he did it my way," Moses said of the new mayor. "Didn't listen to those people who live there. What do they know anyway? You have to think big and think about the future! You want to expand midtown to the west, just do it! How do you think we got Lincoln Center?"

"But tens of thousands live and work here," I said.

"Look at this neighborhood, it's such a mess you might just as well start all over again. You've got the Port Authority Bus Terminal with all those monster buses, all those ugly parking lots, the access roads to the Lincoln Tunnel, the rail yards, a bunch of small warehouses and industries. And there sits the lonely Javits Convention Center. Who would want to live here or even visit with all this noise and pollution? The mayor's got the right idea. Change its name from Hells Kitchen to Midtown West. Turn it into a high rise business district. Get the people off the ground."

MIXED USE

"But this area between Eighth and Ninth Avenues is supposed to be for mixed use," I said. "What do you think about that, Bob? You were always for the separation of uses."

"That's what happens when everybody reads Jane Jacobs and all that garbage about a fine-grained mixture of uses," Moses replied. [see The Death and Life of Great American Cities on the Land Use book list]. "They start muttering that stuff and pretty soon they believe in it. But if you read the city's plan (and I always do my homework) what they're really doing is converting it to a mid-rise and high-rise residential district by letting people build new apartment buildings. That will jack up rents so that none of the small businesses will stay. So it won't be 'mixed use.' The planners are just being clever, God bless them.

"The same thing with the Special Garment District," Moses continued. "That district, on the east end of Hells Kitchen, was set up to protect the garment industry. The planners know the special district rules are only there to protect those jobs, which aren't really good jobs like those in the finance and banking sectors. So the city's going to allow high rise offices to be built there. That's going to encourage speculation and create political pressure to drop the special district protections. You understand that's not the way I got rid of industry. I would just go in with my urban renewal powers, take the land, knock everything down and start all over again. But these planners don't have the courage it takes. They just follow the big private developers and hide behind the zoning rules. I did everything with strong public authorities."

THE #7 SUBWAY LINE

"Bob, what do you think about the idea of extending the #7 subway line? You were never an advocate of mass transit."

"Well, it's only a little more than a mile. It's not like putting in a new subway line or putting more buses on the streets. If it helps develop the area, I can live with it."

"Bob, instead of spending a couple of billion dollars to build a mile of subway line, why not build a trolley (call it "light rail" if you will) from Times Square at one-tenth the cost?" There are many such proposals. "Then the city could really create a pedestrian-friendly midtown. They would divert traffic from midtown so trolleys could run all day and night from Times Square to the waterfront and Convention Center."

"You Ivory Tower intellectuals are all the same!" Moses exclaimed impatiently. "Trolleys died before I did. You can't interfere with the God-given right of every American to drive wherever they want and whenever they want."

"So you must like the city's plan to shut down all the parking lots in Hells Kitchen - excuse me, West Midtown - so developers can build high rises on them, and build parking garages with even more spaces." I said.

He nodded his head in agreement.

"But that will encourage more traffic in the area, not less," I said.

"Traffic congestion means the city's a success," said Moses. "Besides, the city can always build more highways and widen streets."

It's that kind of thinking that keeps more people from coming to the city, but I didn't want to get him mad. He clearly hadn't lost his faith in the ability to engineer the city out of its problems.

ZONING BONUSES

"Bob, what do you think about the city's idea of giving zoning bonuses to developers? They'll let them build up to 50 percent more than the zoning would allow if the developers give the city money to pay for public infrastructure improvements in the area. Neat idea, huh?"

"Hey, that's a good one," Moses replied. "You know, a trick like that worked in Battery Park City so it could work here too. Proceeds from all that upscale development in Battery Park City were supposed to go into a trust fund that was to finance low- and moderate-income housing. About half the money never got collected and no one knows what happened to the rest of it. Neat idea when you've got a budget deficit. Of course Mayor Bloomberg will have to cut something else to pay for the infrastructure in West Midtown. By then nobody will remember the zoning bonus."

THE STADIUM

"And what do you think about the stadium proposal?"

"This kind of thing still stirs my heart," Moses said. "When you had all that opposition to building a stadium on the west side of Manhattan, the city came up with the Olympics 2012 plan. A stroke of genius. The Olympics plan was really done my way, by the specialists and without all those noisy neighborhood people. So now the loud-mouth nay sayers have to make a case not only against a stadium but the whole Olympics Axis." (See the Olympic 'X'.)

PUBLIC HOUSING

"Bob, you built a lot of public housing," I said. "But there's no mention of low-income housing in the plan for West Midtown."

"I only built public housing because I had to put the people I relocated somewhere," Moses replied, "and besides the federal government paid for it. Today all the feds do is give tax breaks. Happily, most people in Hells Kitchen were already forced to move. West Midtown will have midtown rents, so there won't be any place for poor people. Hells Kitchen will be no more. That's progress!"

OPEN SPACE NETWORK

"Bob, the plan has this open space network running through it, and the waterfront access. What do you think about that?"

"Now this is a bit ridiculous," Moses said. "What they're proposing isn't open space, it's just a bunch of trees on the street and wide sidewalks for the tourists. You wanna see open space go to Jones Beach and the other great parks I built. They put a little walkway on the waterfront and call it a park! Anyway, I guess parks don't belong in the city."

I thanked Robert Moses for the exciting walk and the lesson in city planning. After I woke up I looked around for my copy of Jane Jacobs.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Planners Network Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

Lots Of New Plans; Any New Visions?

Lately lots of planning has been going on in New York City -- long-range planning, looking far into the future, envisioning what the city will be like in 10 or 20 years. Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently announced a broad plan for Lower Manhattan and a housing plan for the city. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation recently unveiled nine designs for the World Trade Center site and is getting ready to announce a master plan for the site. We also have an ambitious plan for the 2012 Olympics. And, though most citizens haven't heard about it, the Department of City Planning has a strategic plan. Even the media has the visioning bug. The New York Times asked twelve prominent New Yorkers on January 5 to look into their crystal balls. Civic groups have been leaders when it comes to looking into the future, as witnessed by the array of civic groups that have come forward to discuss rebuilding lower Manhattan after 9/11. Before the last mayoral election, civic groups went into high gear, hoping newly elected officials would heed their plans. Some were quite successful, like the long-range housing plan developed by Housing First!, a coalition of housing and development groups, and the plan for solid waste by the Consumer's Union/Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods, both of which formed the basis for recent policy initiatives in City Hall.

So these days lots of people are thinking about the future of the city. One of the more surprising turns is that even government is getting in on the act. In fact, there seems to be a shift in City Hall, small but significant, away from the short-term, narrow planning that has characterized government ever since the first fiscal crisis in the 1970s. This is especially notable at a time when the current fiscal crisis is pulling decision makers toward short-term solutions to plug holes in the budget.

Legacy of Fiscal Crisis

Unlike many other cities in New York State, New York City has never approved a broad, comprehensive master plan that could serve as a guide in making policy over a long period of time. It's probably just as well. New York City is too big, diverse and complex for a single plan. Would you want an all-powerful planning agency made up of technocrats in a downtown office drawing up blueprints for your neighborhood? Could they possibly understand the diverse realities and needs in this multi-cultural city with hundreds of diverse neighborhoods? That is why the only planning that makes sense in New York has to be based on the communities and involve the communities. There can still be a city-wide vision and a broad city-wide strategy, but it has to relate closely to the city's diverse communities.

Some argue that New York is already developed, so that much of what government has to do is manage the city, not dream up grandiose plans for the future. The problem with this argument is that even the most stable parts of the city are changing all the time. People's problems and needs change, and if government and neighborhoods can anticipate change they can also create it.

While it's probably impossible to have a single monolithic vision and plan for the future of the city, it does make perfect sense to have many. In fact, the city's charter recognizes this (in Section 197-a) and gives government and neighborhoods, through the community boards, the authority to develop a whole range of possible plans. According to the guidelines set out by the Department of City Planning, a plan can cover an area as small as one city block, a neighborhood of 100,000 people, or several neighborhoods. It can cover economic and social development as well as physical development.

Limited Visions

Despite the signs of progress, there is still a lot of short-term thinking amid the strategic planning. Too much of what passes for planning is akin to the kind of strategic planning done by corporations to mask what is basically short-term, bottom-line thinking.

City agencies do strategic plans, but they are limited to their own goals and priorities. They are developed internally, without citizen participation, and are limited to the functions the agencies serve. Agency plans can change abruptly when the mayor leaves office. Especially since term limits, really visionary, long-range thinking is impractical when the mayor, city council members and other elected officials barely serve long enough to learn how things work.

There are also many questions about the new wave of planning initiatives. Are the plans for lower Manhattan anything more than icing on the cake for big real estate deals? Are the plans for Olympics 2012 any more than a collection of mammoth public works projects aimed at spurring development on a few key sites? Are we witnessing a rebirth of the spirit of Robert Moses, the great master planner of the 20th Century who destroyed communities to build highways and high rises? Where, among all these plans, is the overall strategy for the city? Is it in the minds of the mayor and his aides, where it doesn't get debated in the messy process of formal plan approval where diverse communities can be heard? And amid all the big plans for changing the physical city, where are the strategies and plans to improve the quality of neighborhood environments, education, health care, employment, and affordable housing?

Department of City Planning

A newcomer to the city might wonder how the city's officials envision the future of the city, and they might, logically, go to the Department of City Planning (DCP). The Department of City Planning's Strategic Policy Statement outlines eleven priorities. However, they are the agency's priorities, developed by and for the agency, not necessarily priorities for all of us. Our newcomer might be disappointed that about half of them have to do with making changes in zoning regulations to promote new development – perhaps a worthy cause in some cases but obviously there is a lot more to the life of the city that zoning does not and cannot deal with. Zoning rules govern how land can be used, so they are of primary importance to developers. But zoning is an arcane system of regulations that only a few technocrats understand. It is not a plan, but is too often used as a substitute for a plan.

Our newcomer would also be disappointed that the Department of City Planning does not have many plans. In this city with hundreds of diverse neighborhoods, there are no more than a dozen or so approved community plans, and most of them were done at the initiative of the communities. The planning department's strategic policy statement goes beyond zoning when discussing a regional transportation agenda, public access to the waterfront, and the promotion of excellence in design. In these areas the department has made major advances in the last decade, including a waterfront plan, bicycle master plan, ferry plan, etc. Perhaps the new-found passion for planning that has infected the city will flourish anew in the Department of City Planning?

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Planners Network Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.