Police Whistleblowers

Eleven years ago, Detective Investigator Jeff Baird thought the people in power would protect him.

His testimony exposing misconduct within the Internal Affairs Division was a key part of the Mollen Commission. Baird told city officials how officers within his division would create secret files designed to hide evidence that pointed to corruption and misconduct within the department.

“I was only interested in positive change,” said Baird, 49. “I didn’t think the retaliation would come.”

But the retribution that followed would last the rest of his career—and beyond. Baird was shunned by many of his fellow officers and harassed by others. Transfers to different units quickly stalled a once promising career, according to Baird, who also said there was even a warning that his life was in danger.

Baird was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder by his psychologist and applied to receive a special accident disability pension. The police medical board disputed this, however. The case went to court, with city lawyers arguing that Baird only deserved ordinary benefits.

In April, a Manhattan judge sharply criticized the city for denying Baird’s claim, calling its arguments “pitiful.”

"In short, NYPD subjected [Baird] to an insidious 'death of a thousand cuts' in retaliation for his work on the Mollen Commission, with the Medical Board's refusal to even address the cause of his condition being the last gash. This the court will not condone.,” Judge Louis York reportedlysaid in his ruling in favor of Baird. The city is appealing.

Baird’s story is not unique, as other officers who have sought to expose misconduct within the police department have similar tales. Through the years there has been much talk about how to make police whistleblowers feel safe when coming forward to talk about misconduct and corruption. In a recent inquiry, however, a whistleblower has yet again come forward with claims of being subject to retribution rather than thanks.

The VIPER Division

Sgt. John Marchisotto, a supervisor in a Staten Island unit of the VIPER division, which is in charge of monitoring all surveillance within public housing, has said he began writing memos and letters to department leaders in January outlining how officers routinely watched movies or slept while on duty. During this time he also charged that a female supervisor sexually harassed him.

In April, it was reported that Internal Affairs was investigating how a recording of a March suicide taken by the VIPER division wound up on a website. Later that month, the City Council held hearings to examine VIPER, and Marchisotto spoke out against the division. He also spoke to television reporters and held a press conference outlining his allegations.

In City Council hearings, a housing supervisor admitted that many officers monitoring surveillance cameras in housing developments have pending criminal or administrative charges. Manhattan borough president C. Virginia Fields called for more stringent controls on the VIPER unit. The police department has since pledged to review its staffing policies.

Meanwhile, Marchisotto faces three departmental charges related to a WABC news report.

In that report, Marchisotto said he had already faced some retribution. Marchisotto said a group of officers angrily came to his home late at night, and that the department, claiming that he was mentally disturbed, has taken away his guns and placed him on restricted duty.

"You report misconduct, serious misconduct, or anything in the police department they will try to make you look like you're crazy. They will try to discredit you as a complainant and they're pretty good at that," Marchisotto told Channel 7. Police say Marchisotto abused his authority as a supervisor and shouldn’t have videotaped inside his unit. Several stories have cited anonymous and high-ranking police sources that call Marchisotto a chronic malcontent. But in a May press conference, Marchisotto stood with New York State Assemblyman Keith Wright (D-Manhattan), the chairman of the assembly's sub-committee on public housing. Wright said in a press conference that “on the surface of it” the charges against Marchisotto look “quite bogus.”

Also standing by Marchisotto is Lt. Eric Adams, spokesman for 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care.

“The police department did not bring or file any internal charges on any of the men John mentioned,” noted Adams. “No charges handed out against them—yet the discipline was taken against the whistleblower.”

Marchisotto could not be reached for this story. Police did not respond to a list of faxed questions.

Blue Wall of Silence

“We need to protect whistleblowers as best we can,”said Norman Siegel, a civil rights attorney and former head of the New York Civil Liberties Union. Siegel has offered his services to Marchisotto.

The city has a whistleblower law on the books designed to protect those that expose wrongdoing, but, even if strengthened, such a law will not eliminate retaliation towards whistleblowers, said Siegel. He suggests a unit should be set up within the Public Advocate’s office to protect whistleblowers across all city departments (Siegel has run for the Public Advocate).

And 10 years after the Mollen Commission recommended it, Baird would like to see an independent agency with enough power to oversee the police department. The Commission to Combat Police Corruption was created as a result of the Mollen Commission, but that group has been criticized for being irrelevant. It went for more than a year-and-a-half in the Bloomberg administration without any board members.

Efforts to create a powerful agency with oversight authority failed largely due to staunch opposition from then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. Occasionally, the police department has sought to take extra steps to protect whistleblowers and make the department more welcome to criticism. In 1998, then-Commissioner Howard Safir talked publicly about creating ways to reward whistleblowers. But Baird no longer trusts the police to police themselves.

“There’s never going to be any real reform within the police department because they crush people like myself who come forward,” said Baird.Â

Withholding Rent While On Welfare

New York’s highest court, the Court of Appeals, has determined that a tenant whose rent is paid in whole or in part by New York City’s Human Resources Administration – welfare -- cannot withhold payment to her landlord even if there are dangerous violations in the building.

In the case entitled Matter of Notre Dame Leasing, LLC v Alexandria Rosario, the tenant, Alexandria Rosario, lives with her husband and young children in a Queens apartment building owned by Notre Dame Leasing. In January 2000, Notre Dame, the landlord, commenced a Civil Court summary nonpayment proceeding, claiming that $1,454.43 in rent was due for October 1999 through January 2000. The amount demanded was Rosario’s portion of the rent for four months; the balance had been paid by the city. The tenant’s defense to the nonpayment was that she withheld rent because of conditions that were “dangerous, hazardous or detrimental to life or health.”

Rosario was relying on a 1962 Social Services law known as the Spiegel Law (named for Sam Spiegel, a lower East Side Assemblyman who sponsored the legislation). Records of New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development showed that there were 33 Class B (hazardous) and C (immediately hazardous) violations in the building. The landlord established that some of these had been dismissed, but there were still leaks, electrical wiring violations, and broken windows, according to the tenant’s attorney, Carl Callender of New York Legal Services in Queens, who argued the appeal. Attorney Denise May, of Pennisi Daniels & Norelli, LLP, a firm that represents landlords throughout the city, says the violations were either corrected but not removed from the city agency’s computer, or they were tenant-generated violations such as gates on windows or refusal to grant access to the apartment.

However, none of that was addressed by the Court of Appeals. The single issue decided by the court’s majority was that Rosario could not avail herself of the protection of the Spiegel Law, because the tenant herself had withheld rent, rather than the Human Resources Administration having withheld it, even though the agency has the power to do so. Judge Albert Rosenblatt, writing for the majority of judges, agreed with the landlord’s attorneys, saying, “The tenant contends that she should be able to invoke this defense [the Spiegel Law] whenever there is a qualifying violation in her building, regardless of whether the â€appropriate social services agency’ -- here the HRA -- has first withheld rent on that basis. We conclude that the structure, language, history and legislative intent of the Spiegel Law negate the tenant’s interpretation.”

According to Judge Rosenblatt’s opinion, “The legislature did not intend to make this defense available to individual tenants when public welfare officials themselves recognized no imperative to suspend payment.” The judge wrote, “In an action for eviction or unpaid rent, tenants claiming a breach of warranty of habitability... or who seek an abatement of rent ... for a “rent impairing” violation must nevertheless deposit with the court the amount of rent sought to be recovered.”

All of the Court of Appeal judges agreed that the legislature’s intent in enacting the Spiegel law was to end the state’s “subsidizing of landlords who abuse and exploit welfare tenants, but nevertheless receive guaranteed monthly rent checks,” and to “attack the â€jugular vein’ of the slumlord by temporarily withholding payments of rent until hazardous and dangerous violations are cleared.” The Spiegel law was to “establish that public funds should not be used to further the continuance of any building which is substandard,” and “to correct the anomalous condition wherein one municipal department seeks to prevent slum and dangerous conditions from being maintained at the same time that another governmental unit is financially rewarding such maintenance.”

But dissenting Judges Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick and George Bundy Smith, who were both judges in New York City before being appointed to the Court of Appeals, disagreed with the majority. “There is nothing in the provision requiring that the agency must act first to withhold rent on the tenant’s behalf,” they wrote. “The plain language of the statute permits a tenant to invoke the Spiegel law defense for nonpayment of rent, regardless of whether there has been a prior withholding of rent by the public welfare agency, here the New York City Human Resources Administration.” Going back to the Spiegel law’s history, the dissenters quoted, “[t]he legislature hereby finds and declares that certain evils and abuses exist which have caused many tenants, who are welfare recipients, to suffer untold hardships, deprivation of services and deterioration of housing facilities because certain landlords have been exploiting such tenants by failing to make necessary repairs and by neglecting to afford necessary services in violation of the laws of the state.... Allowing tenants to withhold rent themselves continues to further the purpose of the statute, especially in light of the present situation where public welfare officials apparently are not using their statutory power to withhold rent when violations are present. “

Still, May, counsel to the landlord, says “Social services or welfare will withhold the rent if they find dangerous conditions. But they never meant to give tenants a sword to control the money.” Tenants, she says, “now have more protections and can negotiate the system, which they couldn’t do in 1962 when Housing Court didn’t even exist. It’s Legal Services reawakening a statute that everybody had forgotten about.”

But the result of this opinion, says, Andrew A. Scherer, executive director of Legal Services of New York City, and the author of Residential Landlord-Tenant Law in New York, is that “people on public assistance in unsafe, unhealthy buildings, are not going to be able to avail themselves of a law designed to protect them.” Most low-income tenants do not have lawyers, and Scherer says “can neither negotiate the system nor assert sufficient pressure to obtain necessary repairs. The Court of Appeals decision ignores the plain language of the law and its statutory intent and guts a powerful tool for addressing deplorable housing conditions. Because Spiegel Law defenses specifically exempt rent from the deposit requirement of the Rent Regulation Reform Act of 1997, it was revived by the rent deposit law which forces tenants to deposit rents in order to litigate defenses to eviction proceedings. It makes it impossible for tenants to take advantage of something that was created for them.”

Both sides agree that tenants who receive welfare will not be able to withhold rent regardless of their housing conditions, but will have to rely on the city to do it for them.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

Why Is There A Plunge In Crime?

There is no doubt that from 1991 through 2002 New York City experienced a remarkable drop in crime. From an analysis(PDF Format) presented at a conference in Italy by two US Department of Justice statisticians in late 2003, one can see that no matter how one looks at it, crime dropped massively in New York City. Yet the popular explanation for the decline, favored by a former police commissioner and a former mayor and many crime specialists, no longer seems as convincing as it once did. How can we be sure that the "reported crime rate" is the real crime rate? More importantly, how do we know if the crime rate is truly dropping and how fast it is dropping?

Recently, Newsday uncovered some false counting of certain crime incidents in one precinct, while the police union claimed that the continuing decline was suspicious in light of some staffing reductions. The city dismissed these charges. (Read a discussion of this on Gotham Gazette's crime topic page.) This controversy points up a fact well known to those who deal with crime statistics: the "official crime" rate depends on crimes being reported to the police by the crime victims and accurately recorded.

GAUGING THE DROP IN CRIME

The FBI through their Uniform Crime Reportingsystem keeps track of crime statistics for eight selected offenses: 1) murder and non-negligent manslaughter 2) forcible rape 3) robbery 4) aggravated assault 5) burglary 6) larceny-theft 7) motor vehicle theft, and 8) arson.

Each police jurisdiction throughout the United States, including New York City, submits periodic data that gives reported crimes and arrests in these areas. Data from this system form the raw material for comparing crime rates in the major cities, and for tracking reported crime nationally.

Most crimes remain unpunished, and many remain unreported. This fact makes measuring crime very difficult. Complicating the matter further is the fact that the "official reporters" of crime statistics are those charged with finding and catching offenders, the police forces themselves. Often there is pressure to have a lower crime rate, which can cause crime to be unreported or reclassified. Murder, of course, is a special case. Most murders do end up being reported to the police. Also since murder results in death, each murder also creates a vital statistics record. Reporting of other crimes varies greatly. Petty thefts often go unreported. Some muggings, assaults and rapes also remain unreported. Automobile theft, because owners need the police report to make a claim is much more likely to be reported.

Researchers knew for years that much crime goes unreported to the police, while some police departments may be better at reporting crime than others. For these reasons, the US developed a measure of crime independent of police reporting. Since 1973, the Bureau of Justice Statistics has conducted a "crime victimization study," where residents 12 or older are asked to describe crimes for which they were the victim. New York City is one of the 12 cities where a special local survey is done.

COMPARING OFFICIAL AND SURVEYED CRIME

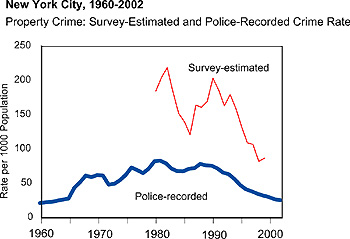

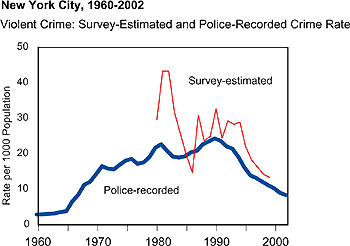

For New York City it is possible to compare official crime statistics with survey results for several years. The accompanying charts present data for property crime and for violent crime based upon both official and survey statistics. Looking first at property crime, in New York City the number of property crimes reported by the survey is much greater than that reported to the police. Indeed, in some years it is several times greater. Both the reported crime and the surveyed crime show a marked decrease in the 1990s. When one looks at violent crime one sees the same marked decline. However, a much higher proportion of violent crime than of property crime is brought to the attention of the police.

Not only has New York City's crime drop been significant and sustained, it also is corroborated with the decline in the crime survey. For murders, the decline is mirrored by that for homicide reported through the vital statistics system. New York City is now the safest large city in the US, the one with the lowest crime rate.

EXPLAINING THE DROP

Former Commissioner William Bratton and his late deputy Jack Naples along with former Mayor Rudy Giuliani had a ready explanation, their implementation of strategies based upon the so-called "Broken Windows" theory. The theory has been one of the most important in criminology. It was first proposed in an article published 20 years ago in The Atlantic Monthly, written by Dr. James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. The theory provided the intellectual foundation for a crackdown on "quality of life" crimes in New York City. Today, "broken windows" policing is endorsed by police chiefs across the country, its proponents sought out for lectures and consulting around the world. (Several books taking various perspectives are mentioned in Gotham Gazette round-up of crime books.)

Recently, this theory has been seriously challenged by a rigorous studycosting over $50 million carried out in Chicago by Professor Felton Earls of Harvard, and his fellow researchers, Robert Sampson also of Harvard, Steven Raudenbush of the University of Michigan and Jeanne Brooks Gunn of Columbia. Earls and his colleagues argue that the most important influence on a neighborhood's crime rate are neighbors' willingness to act, when needed, for one another's benefit, and particularly for the benefit of one another's children. And they present compelling and rigorous scientific evidence to back up their argument. "It is far and away the most important research insight in the last decade," said Jeremy Travis, former director of the National Institute of Justice. "I think it will shape policy for the next generation." Many find their work controversial. One of their original articles was attacked on the floor of Congress, while winning several prestigious awards by professional associations.

Dr. Wilson recently conceded that the "broken windows" theory lacked substantive scientific evidence that it worked. "I still to this day do not know if improving order will or will not reduce crime," Dr. Wilson, now a professor emeritus at the University of California, Los Angeles, recently told the New York Times. "People have not understood that this was a speculation." So crime continues to decline in New York City as it has for more than a decade, but we still do not know the reason why.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.