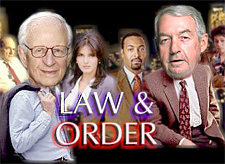

The DAs Of New York

Manhattan D.A. Robert Morgenthau (left) and Brooklyn D.A. Charles Hynes (right) superimposed in the foreground of a promotional photograph for the TV series. Gotham Gazette's Campaign 2005: |

Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau must hope that life does not imitate art. When the television series Law & Order debuted in 1990, the district attorney was Adam Schiff, a character modeled on real-life DA Morgenthau, who had already occupied the office for 15 years. Like his counterpart, Schiff, portrayed by Steven Hill, won acclaim and respect for his work. But in 2000, Schiff was replaced by a younger, female DA.

This was a departure from the real-life district attorneys of New York City, who have often been given what amounts to life-time tenure. Morgenthau, at the age of 85, is seeking his ninth term as Manhattan DA. But former State Supreme Court Judge Leslie Crocker Snyder, age 62, is mounting a credible campaign to unseat him. Perhaps she got the idea she actually has a chance from the goings-on on Law & Order; after all, she works as a consultant for the show.

In Brooklyn, Charles Hynes, the only other New York City district attorney up for re-election this year, also faces an especially tough battle, with as many as six opponents vying for his job.

The two races (the other three DAs will not face re-election until 2007) have put unusual attention on an office that lawyers -- and criminals – realize holds huge power but that most New Yorkers know largely from television series and mystery novels. Like the television DAs, the real ones must regularly deal with some of the hottest controversies of the day and cases “ripped from the headlines.” The DAs must also perform a complicated juggling act. They are supposed to be apolitical but must run for office as a party candidate. They must dispense justice fairly but know they can face harsh public criticism for failing to go after certain crimes or for failing to win convictions.

THE JOB

District attorneys serve as the top prosecutors and chief law enforcement officers in their counties, investigating and prosecuting violations of city and state law. In this capacity, the five New York City DAs –- one for each borough -– prosecuted almost 87,000 crimes in 2003, according to statistics compiled by the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services.

New York State created the job of a county prosecutor in 1796, although back then they were appointed. The position became an elected office following a constitutional convention in 1846.

(These positions, which enforce New York State statutes and New York City ordinances, should not be confused with the Office of the United States Attorney, which prosecutes federal crimes: There are four U.S. Attorneys in New York State, for the Eastern District, based in Brooklyn; for the Southern District, based in Manhattan; for the Northern District, based in Syracuse; and for the Western District, based in Rochester.)

Even in these days of comparatively low crime rates, enforcing the criminal laws in New York City represents an enormous and expensive undertaking. The DAs' budget, part of the overall city budget, totals about $188 million. Each office, except for Staten Island, employs hundreds. The Queens DA, for example, supervises about 260 lawyers.

Running such an operation, says John Pollok, a defense attorney who heads the Criminal Courts Committee for the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, requires that a person be a good administrator and a scholar who knows what the law is. Ideally he or she (all are currently men) should be apolitical.

The people who become DAs in New York City tend to hold their offices for decades, winning one four-year term after another. Indeed, no one can recall a single case of an incumbent, elected New York City district attorney ever having been defeated for re-election. In Manhattan, there have been only three elected district attorneys – Thomas Dewey, Frank Hogan and Morgenthau – since 1937. In Hogan’s bid for a ninth term in 1973, he beat back a stiff primary challenge, only to be admitted to the hospital suffering from a stroke and lung tumor two months later. He still won the general election in November -- but died soon after.

From most senior to most junior the current DAs are:

Robert Morgenthau (Manhattan):

In 1974, Morgenthau defeated Richard Kuh, who had been appointed to replace Hogan. He has not faced a serious challenger since C. Vernon Mason in 1985 and ran unopposed in 2001, when he was already 82.

Robert Johnson (Bronx):

A former criminal court judge, Johnson won election to the post following the death of long-time Bronx DA Mario Merola in 1988 and became the first black district attorney ever in New York State.

Charles Hynes (Brooklyn):

After coming to prominence for his role as special prosecutor in the Howard Beach racial murder case of 1986, Hynes, a former city fire commissioner and prosecutor, won election in 1989 when Elizabeth Holtzman left the DA’s office to become New York City comptroller. He has since tried for other office – running unsuccessfully for governor in 1998 – but has kept his Brooklyn post.

Richard Brown (Queens):

The former appellate court judge was appointed to his post by Governor Mario Cuomo in 1991, winning his first election to the office five months later.

Dennis Donovan (Staten Island):

The first Republican DA in the borough in 50 years, Donovan was elected in 2003 after incumbent Democratic DA William Murphy decided not to run again. Donovan formerly worked as a narcotics prosecutor in the Manhattan DA’s office and served as deputy borough president.

POLITICAL ISSUES

Like judges, these DAs hold an unusual position in the political landscape. They run for office on a party line, raise money for campaigns and seek endorsements from unions and political clubs. But a code of conduct limits just how political they can be. They cannot belong to a political club, endorse candidates or speak at political functions.

Yet they must frequently make decisions on some of the leading political controversies of the day.

They must choose what types of crime to pursue. Crime may be down but there is still far too much of it in New York for DAs to go after every offence – from spitting on the sidewalk to prostitution to insurance fraud.

A lack of money and staff complicates the decisions. New York DAs saw their budgets cut by 12 percent between 2001 and 2004, according to the New York Law Journal, although no budget cuts are proposed for this year. The cuts mean fewer lawyers –- a decrease of 18 percent in Queens -- and thus fewer prosecutions as well.

A decision on whether and (and how) to prosecute a case can be extremely volatile. Over the years, critics have complained, for example, that the city prosecutes drug use in low-income minority neighborhood far more aggressively than similar drug use on Wall Street.

Police shootings pose a particular quandary for prosecutors. They work with, and rely upon, the police. But many in the city demand that the police be brought to justice, particularly in cases where race plays a role.

Choosing the charge, and therefore the possible penalty, also can be fraught with controversy, particularly if capital punishment comes into the picture. From 1995 to 2004, when New York had a capital punishment law, district attorneys had a fair degree of discretion about whether to seek the death penalty. The New York DAs varied widely in their use of the authority.

Hynes and Brown both sought the death penalty in a number of cases. Morgenthau never did, opposed to it on principle, and never suffered any political consequences for his position. But when Bronx D.A. Johnson refused to seek the death penalty in the case of Angel Diaz, who was accused of killing a police officer, Governor George Pataki removed Johnson from the case, bringing in then State Attorney General Dennis Vacco to handle to prosecution. (Diaz committed suicide before the case could come to trial.)

Today, following a Court of Appeals ruling that found the law to be unconstitutional, New York has no death penalty. Most of the candidates for DA this year expect it to remain that way, although Republicans in the State Senate have said they will try to force a vote on the issue.

DRUG LAWS

No issue has focused as much attention on the political role of district attorneys as the so-called Rockefeller drug laws. By limiting a judge’s discretion in setting sentences, the laws put more power in the hands of prosecutors. As enthusiasm for the laws dwindled over the years among a wide cross-section of New York's public and public officials, many district attorneys remained staunch supporters. "We don't support reduction in sentencing," Robert Carney, president of the New York State District Attorneys Association said in 2001. "If you take the minimum away, it removes the leverage that prosecutors have to obtain pleas and information about drug trafficking networks. We've solved murder cases using these laws." The DAs' position, some say, kept the laws intact.

But last fall saw a shift. In Albany County, longtime DA Paul Clyne, a strong supporter of the drug laws, was defeated in the Democratic primary by David Soares, a proponent of reform who went on to victory in the general election. In his primary campaign, Soares distributed flyers reading, “Paul Clyne supports the failed Rockefeller Drug Laws that cost taxpayers $550 million every year. Paul Clyne supports the Rockefeller Drug Laws that cost young people their futures.”

“The Soares victory in Albany was a wake-up call to a lot of district attorneys,” former State Senator John Dunne, who once supported the drug laws but now opposes them, told the New York Law Journal. “They have to run every four years, and this is an issue that’s not going to go away.”

Following the Albany election, Morgenthau, who had already supported reform, reportedly urged Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver to change the Rockefeller laws. And the legislature did finally change some of the sentences. But most of the New York’s DA candidates this year say they favor further reform of the laws, including more provisions for treatment, giving judges more discretion in setting sentences and harsher laws to go after so-called drug kingpins. Morgenthau has not commented on last year’s changes.

THE MANHATTAN RACE

Former Supreme Court Justice Leslie Crocker Snyder does not explicitly mention Robert Morgenthau’s age when she discusses why she thinks he should leave office; she calls for “a DA’s office for the 21st century” with “new vision” and “new energy.”

She faults Morgenthau for putting too much focus on white-collar crimes, which, she says, in many cases could be better handled by federal prosecutors or by the state attorney general. Instead she would shift some of those resources into establishing new initiatives in city schools and in dangerous public housing projects where, she said, there is a lot of crime and people are afraid to report it. She would also focus more on Washington Heights, where language barriers and geographic distance from lower Manhattan keep many residents from getting the law enforcement they deserve. And she would create an anti-terrorism bureau to analyse information the DA's office has found in the course of drug and other investigations and pass it along to the appropriate federal agency.

Morgenthau has argued that the sharp decline in crime in Manhattan -- down more than in any other borough by some counts -- has freed up resources for white collar-crime.

Although he declined to be interviewed for this article -– on the grounds that he did not have the time and that Snyder has not yet formally declared her candidacy –- he has given a number of interviews in recent months partly in an effort to allay concerns he is too old for the job. “I can’t deny my age, but I’m in perfectly good health,” he told the Daily News. “I bicycle, I sail, I work out on the treadmill.”

Morgenthau is waging a vigorous campaign. He has raised more than $1 million (some of it left over from earlier elections) won endorsements from many Manhattan political clubs and from unions not connected with law enforcement, such as Local 1199 of the Health and Hospital Workers Union.

Snyder once served in the DA’s office, where, she says, she was the first woman allowed to try felony cases, including homicides, and founded and led the Sex Crimes Prosecution Bureau. As a Supreme Court judge, she presided over a number of cases involving dangerous drug gangs. She is not only a consultant to Law & Order; she has appeared in several episodes as a judge.

Although she concedes her attempt to oust Morgenthau will be “a tough race,” she thinks she can win it. “No one has ever scrutinized this [Morgenthau’s] office before,” she said. To advance her cause, she has raised at least $890,000 (including $300,000 from her law firm colleagues) and won support from former U.S. Attorney Mary Jo White, who chairs her campaign, and noted civil rights lawyer Richard Emery, as well as 10 law enforcement unions.

But rightly or wrongly, some view Morgenthau as an icon. “The idea of running against Robert Morgenthau is equivalent to running against J. Edgar Hoover as head of the FBI, if there had been an election for that post,” Michael Hardy, who considered challenging him in 2001, told the New York Law Journal in September of that year.

THE BROOKLYN RACE

Unlike Morgenthau, with his patrician background and apolitical image, Hynes is viewed as a tough political fighter -- too tough some say. Looming over the contest are allegations of widespread political corruption in the borough.

In many respects, this year’s race began in 2001, when Sandra Roper, a largely unknown lawyer, challenged Hynes. She captured almost 40 percent of the vote.

“I was shocked that 37 percent of the people in this community did not support me,” Hynes said, adding that he blames himself for not having spent more time with the citizens of Brooklyn. “It’s the old story,” he said, quoting the late Tip O’Neill, "People will not just vote for you -- people want to be asked.”

Since then, Hynes said, he has spent more time in neighborhoods, at churches, synagogues, senior centers, playing basketball with fifth graders. And he thinks that he has mended fences.

But the candidates running against Hynes see more serious problems, including mismanagement of the office, misuse of resources, poor decisions about which crimes to emphasize, and abuses of power. They all said they could win. “Anybody can be beaten,” said one opponent, State Senator John Sampson.

The challengers so far are:

Braxton Freddie Fenner:

A Brooklyn native, he was admitted to practice as an attorney in 1996.

Arnold Kriss:

A former assistant DA, Kriss also served as a lawyer for the police department. He has been in private practice in Brooklyn for more than 20 years and since 1996, has been counsel for the not for profit corporation that runs the San Gennaro Feast in Little Italy.

Mark Peters:

He worked for five years for the state attorney general, including serving from 2001 to 2004 as chief of Eliot Spitzers’s Public Integrity Unit, which prosecutes political corruption. He is also a former president of Brooklyn's Community School Board 15.

Sandra Roper:

Originally a pharmacist, Roper became a lawyer in the late 1980s, first working for Legal Services and then opening her own practice. She has done extensive work for the NAACP. After her unsuccessful run in 2001, prosecutors charged her with having pilfered legal fees from a former client. The criminal charges were dropped last month after a trial ended in a hung jury – and Roper agreed to refund the money.

John Sampson:

A former staff attorney for the Legal Aid Society, Sampson was elected to the New York State Senate in 1996. He represents the 19th Senatorial District, which encompasses Canarsie, East Flatbush and parts of Brownsville, Crown Heights and East New York. He also continues to work as an attorney with a private law firm.

Paul Wooten:

A Brooklyn lawyer now in private practice, he has served as an assistant DA, counsel to the New York State Black and Puerto Rican Legislative Caucus; and first deputy counsel for the 1989-90 New York Charter Revision Commission. During his career, he has handled class action cases involving Brooklyn, as well as criminal cases.

They tend to express similar criticisms of Hynes. “The management and focus of that offices has been lost, said Sampson. “The current DA has shown he is no longer interested in the job,” said Wooten.

Kriss and Sampson charge that the office has lost 39 percent of its assistant DAs in the past four years and that that has hurt its ability to get convictions in criminal cases and to bring cases to trial in a timely fashion

While they concede that all DAs in the city have lost staff due to budget cuts, they allege that Hynes has exacerbated the situation by having a top-heavy staff and, at times, hiring the wrong people. They cite, for example, his appointment of Howard Golden to a $125,000 a year post in the DA’s office after Golden quit as Brooklyn borough president because of term limits.

“He’s more interested in hiring politicians than prosecutors because he’s more interested in politics than prosecution,” said Peters.

In particular, they say Hynes has not done enough about white collar-crime. To Peters, that means auto insurance fraud. Wooten and Sampson cite predatory lending and identity theft as well.

Hynes denies he has neglected this area but, when asked to cite his accomplishment, tends to mention areas other than prosecution. These include an effort to fight hate crimes and drug abuse by having assistant DAs speak in elementary schools, encouraging drug treatment as an alternative to jail and trying to reduce repeat offenders. “The easiest thing we do is put people in jail, “ Hynes said. The difficult thing is prevention.”

Underlying the race are allegations that corruption is rife in Brooklyn, particularly its courts. So far, Hynes has indicted two judges and the leader of the Brooklyn Democratic Party on corruption charges. But many say this is too little, too late. “All of a sudden he gets the epiphany that there’s corruption going on,” said Sampson. “It’s like Rip Van Winkle.” “You can’t wait for a person to knock on your door and tell you about a crime that’s occurred,” says Kriss.

But Hynes says you do. “You’ve got to get lucky,” he said. “Judges and other politicians are very careful about how they commit corrupt acts.”

In particular, Hynes has not brought any changes explicitly related to the “selling” of judgeship in Brooklyn – a practice many believes is widespread.

“Just wait,” he said.

The race promises to be a rough and tumble battle. A sense of that came in a lengthy Harpers magazine article last fall that accused Hynes, who it depicted as a current day political boss, of unfairly targeting political opponents for prosecution and for using an incorrect voting address. After Hynes threatened a libel suit, the Magazine allowed him to respond in February.

A comment by Hynes that he would “cause pain” to political challengers prompted expressions of outrage from opponents who said they viewed it as another indication that the DA would fight dirty to keep his post. Meanwhile his opponents also freely lob accusations of impropriety and cronyism.

Gotham Gazette's Campaign 2005:

Brooklyn District Attorney

Manhattan District Attorney

Other Articles

First Real Challenge in 20 Years for Manhattan District Attorney

(2/24/05) New York Times

My Journey with the Rockefeller Drug Laws

(2/7/05) Gotham Gazette

Death Penalty

(January 2005) Gotham Gazette Opponents of New York's death penalty law, which was declared unconstitutional last year, see it as a major civil rights issue -- and don't expect to see it reinstated.

Rockefeller Drug Law Reform and Drug Courts">

(January 2005) Gotham Gazette More and more advocates are seeing drug courts as an option that offers some tangible answers to a difficult problem.

Meet the New Boss: Man vs. Machine Politics in Brooklyn

(December 2004) Harpers

DA Hynes's Response to Christopher Ketcham's article

(February 2005) Harpers

The People’s Prosecutor

(9/21/04) The Village Voice

The impacts of last year’s defeat of the incumbent DA in Albany.

Happy 85th Birthday, Bob Morgenthau

(7/26/04) New York Magazine

RELATED LINKS

Staten Island District Attorney

Office of the New York State Attorney General

US Attorney's Office Southern District of New York

(covers Manhattan and the Bronx)

US Attorney's Office Eastern District of New York

(covers Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island)

Protecting Whistleblowers: The New York City False Claims Act

Bracha Graber, a social worker in the city for almost three decades, say she was appalled by the way the city's child welfare agency was falsifying records for foster care services, recording visits to children that never occurred in order to bilk the federal government out of millions of dollars. She sent an anonymous letter to the Commissioner of the Human Resources Administration - anonymous, because she feared that otherwise she might lose her job. Then, she met with officials from the office of both the state and the city comptroller. But her allegations, she says, were ignored. And so she sued, under a law called the Federal False Claims Act.

When the city and state settled the case in 1998, she received $4.9 million of the $49 million (the rest went to the federal government.) "The amount was important to the lawyers," she says. "I never did it for the money."

Now some city officials want to see the city enact a local version of the same law that enabled Graber to come forward. The New York City False Claims Act, passed by the City Council but so far neither vetoed nor signed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, would allow whistleblowers who report fraud to file a civil suit on behalf of the government, earning up to 30 percent of any settlement. The law would focus on fraud among contractors working for the city.

The bill's proponents predict an influx of cash to city coffers. It could also mean more scrutiny of the city's vast network of human services contractors, where fraud can not only lead to cost overruns, but inadequate care for those who need it most. The bill's critics say that the cash incentive could lead to nuisance suits that are indistinguishable from extortion. Graber says that the best thing the law would do would be to protect whistleblowers from getting fired.

Widespread Fraud

Though Graber's lawsuit helped to correct the deficiencies of the city's system of foster care, two recent investigations make it clear that this kind of troubling fraud persists.

In January, the Department of Investigation announced the results of its investigation into foster care provider St. Christopher's Inc., a non-profit based in Dobbs Ferry, which resulted in the cancellation of a three-year, $86 million contract(In PDF Format).

The investigation began when whistleblowers tipped off the department that the child care agency was falsifying child records to fare better at an annual audit done by the city. Now, another foster care agency is reportedlyunder investigation for a similar falsification of records.

The New York Timesrecently ran a lengthy, three-part series scrutinizing Prison Health Services, a private health care agency with a three-year, $300 million contract from the city to care for inmates at city jails. The agency comes under fire from ex-employees and state investigators for poor quality of care, including understaffing practices such as having doctors sign in at certain jails to meet staffing quotas, but work at another jail, or having administrators sign in as doctors without seeing any patients. "The practice is clearly fraudulent," one anonymous ex-employee told the paper, and The New York Times reported whistleblower lawsuits against Prison Health Services elsewhere.

It is in just such cases that the Federal False Claims Act has come in handy. In 2003, a federal official speaking about nursing home regulation testified before Congress(In PDF Format) that, "If resident care is so poor that it effectively represents a failure to provide care, the Federal False Claims Act can be invoked," citing 20 settlements in nursing home cases since 1996, one of which involved criminal charges related to falsifying records in an attempt by a nurse to cover up wrongdoing.

Protecting Whistleblowers

The city already has city employee whistleblower law, but some say it does not go far enough When Graber asked a colleague to contact the Department of Investigation to ask about whether her name would leak out if she came forward, she was told 'Honestly, we'll try to keep it in confidence, but it will probably come out.' City law today requires the Department of Investigation to make "reasonable efforts" to keep city employee whistleblowers' names confidential if they request anonymity.

But for Graber, the lawsuit under the Federal False Claims Act seemed to be the best alternative because "the important thing about that law is it protects you from losing your job."

The current city employee whistleblower law today makes retaliatory action illegal, but some say it does not provide enough protection to prevent an employee from being fired.

A New York False Claims Act, say its supporters, would make it easy for the whistleblower to sue and collect damages, the threat of which keeps most employers from firing whistleblowers. "We have to make sure that their bravery doesn't end up with them losing their livelihood or being subject to some mistreatment," said Evan Thies, communications director for the author of the New York City False Claims Act, Councilmember David Yassky.

Pros And Cons Of The NY False Claims Act

Proponents of the bill cite the city's massive contracts budget(In PDF Format) and predict that the city would gain more than $30 million every year, as more whistleblowers come forward to report false claims.

But the bill, and the federal law on which it is modeled, make some critics cringe. Greed can easily overwhelm any sense of justice, critics argue. A Forbes magazine cover storyin its March 14th issue criticized whistleblowers who spend their time documenting fraud rather than trying to stop it.

The dollars involved are astronomical at the federal level, with the federal government recovering over $12 billion in civil fraud cases since the legislation was passed in 1986. Medicare and Medicaid fraud make up the majority of winning and settled cases filed under the Federal False Claims Act. In 2003, $1.7 out of $2.1 billion recovered was related to health care fraud.

More than half of all cases involving a whistleblower also involve alleged fraud against the Department of Health and Human Services, according to the non-profit group Taxpayers Against Fraud.

In New York, Thies said that the law recognizes the difficulty the Department of Investigation has in investigating every lead on a false claim. In a 2002 report, "The DOI Must Do More To Protect Whistleblowers and City Employees" (in pdf format) an official from the Department of Investigation testified that the agency received an average of 8,500 complaints a year, many from whistleblowers. "It's just that they don't have the staff, or the time," said Thies. The new law would not overburden city lawyers, either, Thies said. While would-be whistleblowers must report their complaint to the city, "the idea here is that the city and taxpayers reap the benefits, but an independent party does all the work."

However, the bill includes language requiring the city to "diligently investigate" all complaints, and then allows city officials to decide case by case how many resources to devote. If the city decides to let outside parties do the investigative work, the success of a case might depend on the industriousness of the whistleblower and the willingness of the whistleblower's lawyer to devote resources to the case.

D.C. lawyer John Boese, a critic of the bill whose client roster includes construction agencies, universities and other government contractors who have been sued under the federal version of the law, spoke before the City Council last year, warning that the law will wind up costing the city, thanks to the cost of investigating claims. Boese also warned that the law, with stiff penalties for contractors, could lead to enough lawsuits to make honest contractors leery of doing business with the city. "To a whistleblower, it's a lot like a lottery ticket," Boese said, "whether you have a good case or a bad case."

Several states have enacted their own statutes. New York State Attorney General Elliott Spitzer has called for a state law.

If the New York City version is signed into law, the city would join Chicago as the only other city giving whistleblowers a chance to sue.Â

The Crime Rate: How Low Can It Go?

|

Nilma Rivas was walking with her grandson in East Harlem early one evening when a group of men in a car began shooting on the sidewalk. A stray bullet hit her in the leg, and she bled to death. She was 52 years old.

“People who knew what to do ran,” Jose Rivera, a resident who witnessed the shooting, told the New York Times. “Those who didn’t know what to do stood there.”

That was in November, 1993, a time when the newspaper could refer to random shootings as "numbingly common."

A dozen years later, Javier Llano, walking in that same neighborhood, is worried about crime too. But the crimes that engage Llano, the district manager of the local community board, are pickpocketing and the theft of items left in the cafeteria at Mount Sinai hospital.

In the decade after Rivas's killing, crime in East Harlem dropped 60 percent. The number of murders in the police precinct where Rivas died dropped from 37 a year to eight.

The story is much the same all over New York City, which has experienced a dramatic drop in crime for 15 years in a row now. In 1990, 2,245 were murdered; in 2004, there were 566 murders citywide. In 1990, 147,123 cars were stolen; in 2004, auto thefts in the city totaled 21,848. The Federal Bureau of Investigation now considers New York the country’s safest big city.

How did this happen? Why did it happen? Mayor Michael Bloomberg credits the policies of his administration and those of his predecessor, and is making the drop in crime a centerpiece of his campaign for re-election. But others offer different explanations. And some experts say that the drop in crime remains a mystery.

Most New Yorkers, though, are probably less interested in why crime has been dropping than in whether it will continue to do so. Some fear an inevitable reversal of the trend, and point to a recent increase in crime in several neighborhoods. (See related story in the Community Gazettes for district 3, Against the Tide, Crime Continues Rising in Chelsea)

With fewer resources allocated to go after crime, some say that the administration is putting itself in a tricky situation. If no one is sure why the crime rate has continued to decrease, how can they know that it won't start to increase? And if Bloomberg and his police commissioner are taking credit for keeping the crime rate down, how can they avoid the blame if it starts to go back up?

BLOOMBERG'S POLICIES

When he succeeded Rudolph Giuliani as mayor in 2002, Mayor Bloomberg vowed he would keep crime down while at the same time improving community relations. In making these promises, he was responding to the dual legacy of Rudolph Giuliani.

Many New Yorkers identified the decline in crime with Giuliani’s tough tactics. Giuliani saw lowering crime rates as his major goal in office, and adopted a relentless policing style to do so, combating minor, so-called quality of life offenses.

On the face of it, Bloomberg’s basic policing philosophy is a continuation of Giuliani’s. Both administrations have focused on cracking down on minor crimes. Bloomberg immediately initiated Operation Clean Sweep upon coming into office to cut down on quality of life offenses. In its first two years, the operation totaled 20,000 arrests and 209 summonses.

Under Bloomberg, courts are not inclined to offer Desk Appearance Tickets – tickets for small crimes intended to move people through the system quickly – meaning that offenders are more likely to spend the night in jail.

The police department is also looking at ways to improve analysis of crime data, setting the stage for targeted operations that resemble those that Giuliani adopted citywide.

“They’re constantly working on being smarter, and putting people where the problems are, and having the data and the information to do it quicker,” said Eli Silverman, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Operation Impact, for example, is the administration’s major such effort. It uses computer-generated statistics to come up with troubled “Impact Zones”, which it then floods with rookie police officers. The administration notes that crime in these areas dropped 26 percent in 2004. It has moved its focus to a new set of areas for 2005.

Limits to Success?

In some cases, though, the idea of saturation seems to be pushed near its limit. While crime declined across the board last year, major felonies were up 2.1 percent on the subway, despite a nearly 40 percent increase in the number of arrests.

Over-reliance on the numbers has also been said to give the department tunnel vision. William Bratton, the police commissioner who established the major policing policies of the Giuliani administration, wrote that reliance on computer-generated statistics tends to reduce focus on things that cannot be measured easily (in pdf format).

The relentless pursuit of lower crime rates through increased police vigilance is also having an effect on the police officers themselves. During the Giuliani years, the pressure to lower crime was seen as reason for overly aggressive tactics; in recent years precincts having trouble bringing down crime through policing have reverted to creative manipulation of the statistics (and, in some cases, outright fabrication.)

Rank-and-file police officers are also without a contract. This, combined with pressure to continuously outperform themselves, has led to an all-time low in morale, according to police union president Patrick Lynch.

Improving on Community Relations?

The policing strategies that Bloomberg has inherited alienated a large swath of the city’s population during the Giuliani administration, particularly the young black and Hispanic men who were most likely to be the targets of crackdowns. They were also linked to high profile police killings and other acts of brutality like the killing of Amadou Diallo and the torture of Abner Louimathat marred the Giuliani administration.

At first glance, such tension has seemed absent from the Bloomberg years.

In truth, though, the number of complaints to the Civilian Complaint Review Board during the Bloomberg years has actually been higher than it was under Giuliani. It continues to rise. In the first six months of 2004 the number of complaints grew about 15 percent as compared to 2003, numbers that the police department dismisses as indicative of increased ease in filing complaints through systems like 311. Young black men are still more likely to file complaints than any other group.

Nor have the last three years been free of innocent victims: a police officer shot and killed Timothy Stansbury while he was walking across the roof of his grandmother’s housing development; Alberta Spruill was killed in her apartment building in Harlem during a faulty raid; a police officer shot and killed African immigrant Ousmane Zongo in a raid that some have criticized as reminiscent of the troubling excesses of the Giuliani years.

What has changed is that these events have failed to develop into widespread discontent. To many, this serves as a testament to the political skills of Bloomberg and Kelly. Their prowess in public relations, some say, has diverted attention away from what really amounts to more of the same.

“Part of the thing that galvanized people was Giuliani with this uncaring attitude, and Bloomberg has not done that,” said Angelo Falcon, president of the Institute for Puerto Rican Policy. “It’s still a serious problem in our communities. What has changed on the ground is that people aren’t paying attention in the same way.”

Others give the current administration more credit, saying that Kelly has cut back on the more aggressive stop-and-frisk tactics that were producing much tension while also reaching out to communities.

“What [Kelly] is saying is that police commanders should stay in touch with their communities, find out what the problems are, attend meetings,” said Edward Mamet, a retired police captain who now works as a police consultant. “It doesn’t have to be in a formal way. It’s a culture that has to be established.”

In East Harlem, says Javier Llano of Community Board 11, police officers not only meet with him, but also with local businesses and community organizations in a way that never happened under Giuliani. These meetings have inspired Llano, he says, to think of new ways to improve the burgeoning relationship between the police and the community.

On the other hand, developing closer relationships with local police officers has had at least one drawback. Officers have recently been coming to Llano with troubling news. Don’t be surprised if the crime rate starts going up, one warned him, because we can’t possibly make it go any lower.

WHY THE DROP IN CRIME?

To accept or reject this argument -- that the crime rate cannot possibly go any lower -- it helps to understand the debate over the causes for the unprecedented decline in crime.

Those trying to explain the drop in crime generally gather into two opposing camps.

On one side are those who believe that poverty, joblessness, and other social and economic factors drive crime rates. According to this view, the nationwide drop in crime during the 1990s was due mainly to the end of the crack cocaine epidemic and the strong economy. New York’s specific success was also credited to a rise in immigrants – who commit fewer crimes – and a drop in the number of young men – who commit more.

The other side of the debate argues that policing was what mattered most, and that New York City’s experience proves that. By adopting the broken windows theory and pioneering Compstat, the New York Police Department had developed new, more effective ways to combat crime.

The New York Police Department underwent major changes in the 1990s that continue to the present day. After increasing significantly in size, it embraced a new philosophy under Giuliani. The broken windows theory holds that unpunished minor offenses led to an atmosphere of disorder that would lead to more major crimes.

The department’s goal became to eliminate that atmosphere. To do so, it employed Compstat, a computer database that created detailed information about crime on a precinct-by-precinct basis. This was neither a technological innovation nor a a completely new idea; Compstat used off-the-shelf software to do something that police had long done by hand. But it allowed the department to do it faster, and it made precincts responsible for their own performances. In monthly meetings, traditional barriers to communication were eliminated.

“We had developed a method to reduce crime and disorder that would work in any city in America – indeed, in any city in the world,” wrote Police Commissioner William Bratton, who implemented Compstat and the broken windows theory in New York.

The ideas spread across the country, but not every city in America adopted them, and skeptics point out that many of these cities saw drops in crime as well. In the 1990s, cities like Boston, San Francisco, and San Diego saw crime drop significantly.

“Long derided by conservatives for its alternative crime policies, San Francisco registered reductions in crime that exceed or equal comparable cities and jurisdictions – including New York,” wrote the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice in a 2002 report (in pdf format).

Recent years have seen some of these successes reversed. At the same time, a fluctuating economy did nothing to reverse the crime rate. Some proponents of the arguments that social and economic drive crime rates were no longer convinced that these arguments gave the full picture.

Andrew Karmen, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Science and the author of New York Murder Mystery, a book about the nationwide decline in crime during the 1990s, points to continuing social factors – more high school students going to college, the continued boom in immigration – while also saying that the police department has been a significant factor.

But the failure of either major theory to explain fully the drop in crime leads Karmen to the conclusion that what is happening in New York is in need of examination outside of the usual argument between the two camps. He has been calling for a non-political commission to study the phenomenon so that policymakers will not be caught unaware when the trend reverses.

“I want to present the whole thing as a mystery and I want to claim that no one knows for sure why crime has dropped so sharply in New York,” he said, which makes it impossible to know when the trend will stop.

HOW LOW CAN THE CRIME RATE GO?

At various times throughout the last 15 years, experts have said that crime had reached its lowest possible level.

“Since you can never eliminate crime, you have to look at what is the satisfactory level of crime that we can tolerate,” said Mamet, the police consultant. Some think that 566 murders is close to the best that New York can hope for.

Whether a certain number of crimes constitute a high or low crime rate is, of course, relative. In the 1950s, 300 or 400 murders were accepted as the average; by 1996, the 1,000-murder mark was considered the “magic number” to beat.

"If at midnight of December 31 the homicide rate is below 1,000, you can bet the corks will be popping at City Hall.” Newsday writer Dennis Duggan predicted several weeks before the end of 1996.

There would hardly be celebration at the mayor’s office if there are anywhere near 1,000 murders this year, just as many European cities would be shocked to suffer from the "low crime rate" that New York enjoys today. The murder rate in New York City, for example, is calculated to be 6.9 per 100,000 people. By contrast, the murder rate in London is 2.4 per 100,000. And whatever the rate, the absolute number of murders in New York City last year was higher than any other city in the United States. Put it all together, and there were as many Americans killed in New York City between 1962 and 2002 as died in the Vietnam War. That doesn't sound very low.

Related Links

New York Police Department

Vera Institute of Justice

Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reports

Bureau of Justice Statistics: Overview of Homicide Trends in the US

Does Policing Matter? An Analysis of the New York City's Police Reforms (by the Manhattan Institute)

Shattering Broken Windows: An Analysis of San Francisco's Alternative Crime Policies (by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice)

Reconsidering the 'Broken Windows' Theory (an audio file by National Public Radio)

Â