Withholding Rent While On Welfare

New York’s highest court, the Court of Appeals, has determined that a tenant whose rent is paid in whole or in part by New York City’s Human Resources Administration – welfare -- cannot withhold payment to her landlord even if there are dangerous violations in the building.

In the case entitled Matter of Notre Dame Leasing, LLC v Alexandria Rosario, the tenant, Alexandria Rosario, lives with her husband and young children in a Queens apartment building owned by Notre Dame Leasing. In January 2000, Notre Dame, the landlord, commenced a Civil Court summary nonpayment proceeding, claiming that $1,454.43 in rent was due for October 1999 through January 2000. The amount demanded was Rosario’s portion of the rent for four months; the balance had been paid by the city. The tenant’s defense to the nonpayment was that she withheld rent because of conditions that were “dangerous, hazardous or detrimental to life or health.”

Rosario was relying on a 1962 Social Services law known as the Spiegel Law (named for Sam Spiegel, a lower East Side Assemblyman who sponsored the legislation). Records of New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development showed that there were 33 Class B (hazardous) and C (immediately hazardous) violations in the building. The landlord established that some of these had been dismissed, but there were still leaks, electrical wiring violations, and broken windows, according to the tenant’s attorney, Carl Callender of New York Legal Services in Queens, who argued the appeal. Attorney Denise May, of Pennisi Daniels & Norelli, LLP, a firm that represents landlords throughout the city, says the violations were either corrected but not removed from the city agency’s computer, or they were tenant-generated violations such as gates on windows or refusal to grant access to the apartment.

However, none of that was addressed by the Court of Appeals. The single issue decided by the court’s majority was that Rosario could not avail herself of the protection of the Spiegel Law, because the tenant herself had withheld rent, rather than the Human Resources Administration having withheld it, even though the agency has the power to do so. Judge Albert Rosenblatt, writing for the majority of judges, agreed with the landlord’s attorneys, saying, “The tenant contends that she should be able to invoke this defense [the Spiegel Law] whenever there is a qualifying violation in her building, regardless of whether the â€appropriate social services agency’ -- here the HRA -- has first withheld rent on that basis. We conclude that the structure, language, history and legislative intent of the Spiegel Law negate the tenant’s interpretation.”

According to Judge Rosenblatt’s opinion, “The legislature did not intend to make this defense available to individual tenants when public welfare officials themselves recognized no imperative to suspend payment.” The judge wrote, “In an action for eviction or unpaid rent, tenants claiming a breach of warranty of habitability... or who seek an abatement of rent ... for a “rent impairing” violation must nevertheless deposit with the court the amount of rent sought to be recovered.”

All of the Court of Appeal judges agreed that the legislature’s intent in enacting the Spiegel law was to end the state’s “subsidizing of landlords who abuse and exploit welfare tenants, but nevertheless receive guaranteed monthly rent checks,” and to “attack the â€jugular vein’ of the slumlord by temporarily withholding payments of rent until hazardous and dangerous violations are cleared.” The Spiegel law was to “establish that public funds should not be used to further the continuance of any building which is substandard,” and “to correct the anomalous condition wherein one municipal department seeks to prevent slum and dangerous conditions from being maintained at the same time that another governmental unit is financially rewarding such maintenance.”

But dissenting Judges Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick and George Bundy Smith, who were both judges in New York City before being appointed to the Court of Appeals, disagreed with the majority. “There is nothing in the provision requiring that the agency must act first to withhold rent on the tenant’s behalf,” they wrote. “The plain language of the statute permits a tenant to invoke the Spiegel law defense for nonpayment of rent, regardless of whether there has been a prior withholding of rent by the public welfare agency, here the New York City Human Resources Administration.” Going back to the Spiegel law’s history, the dissenters quoted, “[t]he legislature hereby finds and declares that certain evils and abuses exist which have caused many tenants, who are welfare recipients, to suffer untold hardships, deprivation of services and deterioration of housing facilities because certain landlords have been exploiting such tenants by failing to make necessary repairs and by neglecting to afford necessary services in violation of the laws of the state.... Allowing tenants to withhold rent themselves continues to further the purpose of the statute, especially in light of the present situation where public welfare officials apparently are not using their statutory power to withhold rent when violations are present. “

Still, May, counsel to the landlord, says “Social services or welfare will withhold the rent if they find dangerous conditions. But they never meant to give tenants a sword to control the money.” Tenants, she says, “now have more protections and can negotiate the system, which they couldn’t do in 1962 when Housing Court didn’t even exist. It’s Legal Services reawakening a statute that everybody had forgotten about.”

But the result of this opinion, says, Andrew A. Scherer, executive director of Legal Services of New York City, and the author of Residential Landlord-Tenant Law in New York, is that “people on public assistance in unsafe, unhealthy buildings, are not going to be able to avail themselves of a law designed to protect them.” Most low-income tenants do not have lawyers, and Scherer says “can neither negotiate the system nor assert sufficient pressure to obtain necessary repairs. The Court of Appeals decision ignores the plain language of the law and its statutory intent and guts a powerful tool for addressing deplorable housing conditions. Because Spiegel Law defenses specifically exempt rent from the deposit requirement of the Rent Regulation Reform Act of 1997, it was revived by the rent deposit law which forces tenants to deposit rents in order to litigate defenses to eviction proceedings. It makes it impossible for tenants to take advantage of something that was created for them.”

Both sides agree that tenants who receive welfare will not be able to withhold rent regardless of their housing conditions, but will have to rely on the city to do it for them.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

Why Is There A Plunge In Crime?

There is no doubt that from 1991 through 2002 New York City experienced a remarkable drop in crime. From an analysis(PDF Format) presented at a conference in Italy by two US Department of Justice statisticians in late 2003, one can see that no matter how one looks at it, crime dropped massively in New York City. Yet the popular explanation for the decline, favored by a former police commissioner and a former mayor and many crime specialists, no longer seems as convincing as it once did. How can we be sure that the "reported crime rate" is the real crime rate? More importantly, how do we know if the crime rate is truly dropping and how fast it is dropping?

Recently, Newsday uncovered some false counting of certain crime incidents in one precinct, while the police union claimed that the continuing decline was suspicious in light of some staffing reductions. The city dismissed these charges. (Read a discussion of this on Gotham Gazette's crime topic page.) This controversy points up a fact well known to those who deal with crime statistics: the "official crime" rate depends on crimes being reported to the police by the crime victims and accurately recorded.

GAUGING THE DROP IN CRIME

The FBI through their Uniform Crime Reportingsystem keeps track of crime statistics for eight selected offenses: 1) murder and non-negligent manslaughter 2) forcible rape 3) robbery 4) aggravated assault 5) burglary 6) larceny-theft 7) motor vehicle theft, and 8) arson.

Each police jurisdiction throughout the United States, including New York City, submits periodic data that gives reported crimes and arrests in these areas. Data from this system form the raw material for comparing crime rates in the major cities, and for tracking reported crime nationally.

Most crimes remain unpunished, and many remain unreported. This fact makes measuring crime very difficult. Complicating the matter further is the fact that the "official reporters" of crime statistics are those charged with finding and catching offenders, the police forces themselves. Often there is pressure to have a lower crime rate, which can cause crime to be unreported or reclassified. Murder, of course, is a special case. Most murders do end up being reported to the police. Also since murder results in death, each murder also creates a vital statistics record. Reporting of other crimes varies greatly. Petty thefts often go unreported. Some muggings, assaults and rapes also remain unreported. Automobile theft, because owners need the police report to make a claim is much more likely to be reported.

Researchers knew for years that much crime goes unreported to the police, while some police departments may be better at reporting crime than others. For these reasons, the US developed a measure of crime independent of police reporting. Since 1973, the Bureau of Justice Statistics has conducted a "crime victimization study," where residents 12 or older are asked to describe crimes for which they were the victim. New York City is one of the 12 cities where a special local survey is done.

COMPARING OFFICIAL AND SURVEYED CRIME

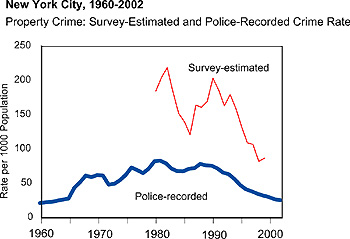

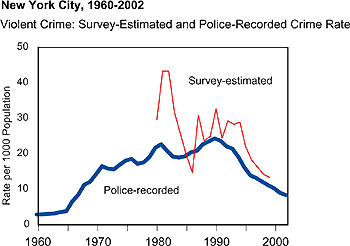

For New York City it is possible to compare official crime statistics with survey results for several years. The accompanying charts present data for property crime and for violent crime based upon both official and survey statistics. Looking first at property crime, in New York City the number of property crimes reported by the survey is much greater than that reported to the police. Indeed, in some years it is several times greater. Both the reported crime and the surveyed crime show a marked decrease in the 1990s. When one looks at violent crime one sees the same marked decline. However, a much higher proportion of violent crime than of property crime is brought to the attention of the police.

Not only has New York City's crime drop been significant and sustained, it also is corroborated with the decline in the crime survey. For murders, the decline is mirrored by that for homicide reported through the vital statistics system. New York City is now the safest large city in the US, the one with the lowest crime rate.

EXPLAINING THE DROP

Former Commissioner William Bratton and his late deputy Jack Naples along with former Mayor Rudy Giuliani had a ready explanation, their implementation of strategies based upon the so-called "Broken Windows" theory. The theory has been one of the most important in criminology. It was first proposed in an article published 20 years ago in The Atlantic Monthly, written by Dr. James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. The theory provided the intellectual foundation for a crackdown on "quality of life" crimes in New York City. Today, "broken windows" policing is endorsed by police chiefs across the country, its proponents sought out for lectures and consulting around the world. (Several books taking various perspectives are mentioned in Gotham Gazette round-up of crime books.)

Recently, this theory has been seriously challenged by a rigorous studycosting over $50 million carried out in Chicago by Professor Felton Earls of Harvard, and his fellow researchers, Robert Sampson also of Harvard, Steven Raudenbush of the University of Michigan and Jeanne Brooks Gunn of Columbia. Earls and his colleagues argue that the most important influence on a neighborhood's crime rate are neighbors' willingness to act, when needed, for one another's benefit, and particularly for the benefit of one another's children. And they present compelling and rigorous scientific evidence to back up their argument. "It is far and away the most important research insight in the last decade," said Jeremy Travis, former director of the National Institute of Justice. "I think it will shape policy for the next generation." Many find their work controversial. One of their original articles was attacked on the floor of Congress, while winning several prestigious awards by professional associations.

Dr. Wilson recently conceded that the "broken windows" theory lacked substantive scientific evidence that it worked. "I still to this day do not know if improving order will or will not reduce crime," Dr. Wilson, now a professor emeritus at the University of California, Los Angeles, recently told the New York Times. "People have not understood that this was a speculation." So crime continues to decline in New York City as it has for more than a decade, but we still do not know the reason why.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

May the Force Be With You

Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly |

When an operative for al-Qaeda named Lyman Farris came to New York, his plan was to take down the Brooklyn Bridge and derail some railway cars. But he looked at the heightened security in the vicinity of the bridge, and changed his mind; the “weather was too hot” to complete the operation.

This one incident was prevented, then, thanks to the counterterrorism policing work of the New York Police Department. Our successes in this area are usually a lot more difficult to measure.

We are now, of course, in a new era. When I came back as police commissioner in New York, having served ten years ago under Mayor David Dinkins, the biggest change for the police in New York was obvious -- the threat of terrorism. It has had an impact on virtually every decision the department has made.

But counterterrorism is just one of the "three C's" that the police department under the Bloomberg administration continues to focus on. We are also moving forward on crime reduction and community relations.

COUNTERTERRORISM

Since 9/11, the police department has taken serious steps to defend our city against terrorism.

We have put into place a counterterrorism bureau, really the first of its kind in the country, which now has 250 officers, and we have reformed our intelligence division.

We have identified people with language skills in the department and certified them. We now have certified 45 Arabic speakers -- more, we believe, than any federal agency that we’re aware of. We have even made them available to federal agencies. In addition, we have Urdu, Pashto, and Hindi speakers.

We have assigned detectives overseas – to Lyon, London, Tel Aviv, Toronto, Montreal, and Singapore. In March, we had someone in Madrid the day of the bombing on that city’s subway. Our world has gotten smaller, and we need information of any sort that’s going to help us better protect this city.

With the advent of the Iraqi war we’ve put in place something called Operation Atlas, which is an overlay security program for sensitive locations throughout the city. We have kept that program in place. Today, we have critical response vehicles that come into Manhattan every day from other locations in the city.

Average New Yorkers are also being more vigilant, and we ask people to continue to look at things through the prism of 9/11. Depending on what is in the news, our counterterrorism hotline averages from 30 to 60 calls a day. There are some very thoughtful calls, many about people taking pictures of infrastructure. We also get many bomb scares and powder droppers.

We log those calls in – we have a database where we log those calls. If that location shows up again, then we’re able to match it with previous calls.

There’s just a lot going on, and it’s an expensive undertaking. We believe it cost us close to $200 million for our counterterrorism programs in the city last year. We’re not getting enough money. In addition, a lot of this money is skewed towards equipment, and not structured for operational costs. We need money for operation expenses on an ongoing, day-to-day basis, not just for equipment.

CRIME PREVENTION

I believe that in certain areas, our counterterrorism tactics are benefiting our crime prevention efforts. On the subway, for instance, crime is the lowest it has been since it has been accurately recorded in the 1960s, which may be in part due to our aggressive counterterrorism efforts.

In other areas, we are looking to combine some of the things we’ve done in counterterrorism with our crime prevention programs, by doing things like incorporating our Hercules program into Operation Impact.

In Operation Impact, we took off across the city and identified locations, primarily based on shootings, that in our view would benefit from an infusion of uniformed police officers alongside officers from narcotics and from the warrant squad. We picked 21 such locations, and put two thirds of our police academy graduating classes from 2003 in these areas. As a result of that infusion of visible police officers crime went down 35 percent in those impact zones in 2003, with shootings down 50 percent. We are seeing the same numbers now in the Impact Zones for 2004.

Now this may not sound revolutionary, but at a time when we have 5,000 fewer officers than we had in October of 2000, this is the type of technique that enables us to continue to reduce crime. Crime rates are now down over three and a half percent this year, after dropping six percent last year, and five percent the year before.

To continue this trend, we’re establishing a crime information center, which will hopefully be functioning by the middle of this summer. We have already established a room at police headquarters; there will be screens that graphically depict crime and we ultimately intend to get that information on PDA’s, hand held devices. The intention is to gather information on a real time basis, digitally analyze it, and push it back out to the field as quickly as possible.

We will use this as an adjunct to Compstat, which is a valuable auditing tool that looks retrospectively at what commands have done to address crime. The police foundation has been very helpful in assisting to put this capacity in place, and obviously the mayor is very interested and involved as well. So that’s the next wave of crime fighting: information.

|

COMMUNITY RELATIONS

All members of the department are aware of the need to communicate with the public. Throughout their careers, we have them in service training. I think our community relations are better now than they’ve ever been.

But every day is a new day in New York, and when we make a mistake in this business, it costs people’s lives.

In the recent shooting of Timothy Stansbury in a Brooklyn housing project, the police department made a mistake, and we said so. It is the policy of this administration, if you make a mistake, to get the facts out as quickly as possible. That’s what we did in the Stansbury case, just as we did with terrible tragedy of Alberta Spruill, who died of a heart attack after several officers mistakenly raided her apartment. I think it cooled the environment.

If you have the facts and they’re obvious, you should get them out, but that is unusual. The Stansbury shooting in Brooklyn was a very simple case: there were two officers together, and one officer observed what happened. There were witnesses in terms of the tangential events that were going on that indicated right away that this was a mistake, so it wasn’t complex. Other shootings are more complicated; it all depends on the circumstance.

It is the nature of police work that we’re going to have tension with some communities because of what we do. We are sometimes the bearer of bad news. We give out traffic summonses, we arrest people, we use force, sometimes deadly force; it’s the nature of police business. People are not always going to love you in some places.

We’re not firefighters – everybody loves a firefighter.

So we have to work on community relations, and I think precinct commanders as a group do a tremendous job in fostering and understanding communications in the communities. We have 76 precincts, and the commanders of these precincts spend a large percentage of their time focused on fostering communication in their communities.

They know they have to do that.

BUILDING A FORCE

Other than terrorism, the biggest change since I left the department is the size of the organization. There has been a merger of the housing police force, the transit police force, all the school safety agents, and traffic enforcement agents. So the department increased significantly in size.

We now have about 51,000 employees.

Though the department has grown, the loss of officers to attrition is an ongoing issue in the police department. We have 5,000 fewer officers below our level in the fall of 2000, because of the budget situation that we find ourselves in. At this time, we have about 36,000 officers; we’re authorized to employ 37,000 officers. We’ll hire up to reach that number in July of that year.

Much of the current loss has its roots as far back as the 1970s. In 1975 there were layoffs in the department because of the serious fiscal crises. The department didn’t start hiring in a significant way until the 1980s. Those people are reaching their twentieth year anniversary, when they can retire at half pay. When police officers hit their twentieth anniversary, about 80 percent retire. Sergeants retire at about a 65 percent rate. So we know that we have to do a big job in recruiting additional people to the department.

Under Mayor Bloomberg, we’ve hired four large classes to address our attrition losses. We’re doing well with our recruiting, and our diversity is improving. The department is about 15 percent African American, about 20 percent Hispanic, and about 3 percent Asian. 16 percent of the department is female. We’re the city agency, I think, that best reflects the population of the city.

Attrition remains an ongoing issue. From recruiting to vetting to training new officers, it is a challenge. I think we’re doing that well. But those three C’s are what this administration is all about.

Raymond Kelly is the police commissioner of New York. This essay was adapted from comments he made at Baruch College.