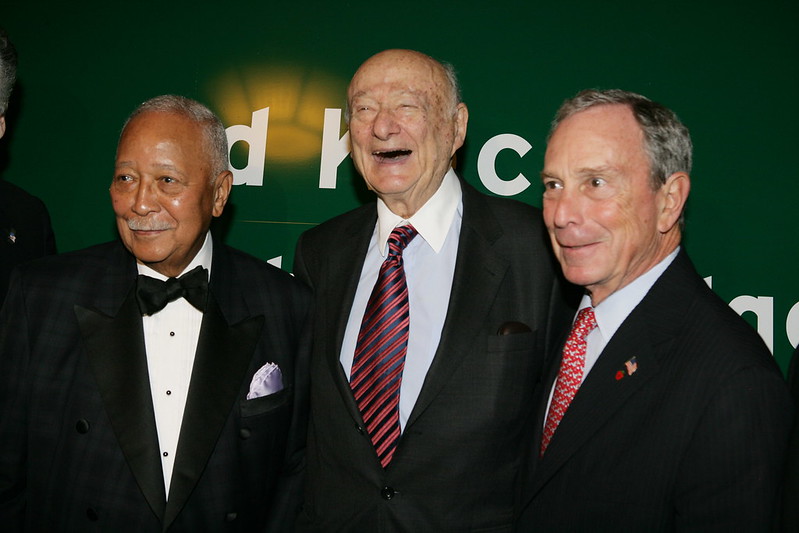

Mayors Dinkins, Koch, Bloomberg (photo: Kristen Artz/City Council)

This is part two of a two-part reflection. Read part one, on searching for New York's soul in literature, here.

By most informed estimates, Fiorello La Guardia stands out as the most admired mayor in the history of New York. That, in itself, tells us something about what New Yorkers expect of their leaders and their city. La Guardia is associated with the progressive ideal that society, through government, has a moral obligation to take care of people who are most in need, people like those who appear in the literature of Diaz, Baldwin, and Kwok.

He carried his message to Washington, and was among those who persuaded President Franklin Roosevelt to launch a New Deal that would rescue the country from a devastating Depression by building infrastructure, public housing, and an ambitious social safety net. That partnership between La Guardia and Roosevelt became a defining formula of progressive governance, holding that the federal government has a crucial role to play in equipping cities and states to meet the needs of their most vulnerable constituents.

That generous instinct was evident in New York before the New Deal. As far back as the 1920s, Governor Al Smith and Mayor Jimmy Walker invested in public works to produce jobs and created public housing to provide subsidized apartments for working people. But the other side of New York that James Baldwin wrote about was also evident then. During La Guardia's tenure, NYCHA consciously chose to segregate housing. The Little Flower was caught off guard in 1935 when rioting broke out in Harlem to protest racism, discrimination, police brutality, and inadequate services. Even in its finest moment, New York progressivism was compromised on issues of race and class.

Progressivism — or mainstream liberalism, as it was called then — would stay on a moderate and steady course beyond the middle of the twentieth century. Mayor Robert Wagner, son of the New Deal Senator, built schools, hospitals and more housing. He breathed life into the municipal labor movement by granting collective bargaining rights to public employees and recognizing their unions. Like La Guardia, Wagner also channeled a limited amount of patronage to Black political leaders. But his gestures on race would prove inadequate. As demands for Black Power replaced the more moderate language of civil rights leaders, a quickened momentum for change outpaced the gradualism of mainstream liberal Democrats whose political base was dependent on white ethnic coalitions.

Mayor John Lindsay embraced an egalitarian and compassionate agenda more aggressively that any of his predecessors. His support of neighborhood government accelerated the political incorporation of Black and Puerto Rican activists. He was the first chief executive to openly oppose discrimination against women and gays. He capitalized on President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs that provided social services to people suffering from poverty. When federal funding to cities became diverted to the Vietnam War and New York’s economy began to buckle under pressure from declining revenue and increasing costs, Lindsay and the inclusive, compassionate liberalism he stood for became a target of a growing conservative backlash. Locally, even newly empowered municipal unions, whose workers advanced progressive demands on economic issues, would occasionally push back when asked to make concessions to Lindsay’s racial agenda.

The fiscal crisis of 1975 that brought the city to the brink of bankruptcy was a major turning point. A spirit of generosity gave way to an emphasis on austerity. Major service cuts and layoffs fell most severely on the most vulnerable people, who were disproportionately Black and Puerto Rican. Mayor Ed Koch epitomized the transition as New York transformed itself from a kinder to a meaner city.

On the one hand, Koch had initiated the most ambitious housing program since the depression; on the other, he was capable of inflammatory rhetoric that fanned the flames of racial animosity. Violent crime reached historic levels. Even David Dinkins, the city’s first Black mayor, could not resist demands for more police protection. Crime did dramatically drop under Mayor Rudy Giuliani, but in the process a disproportionate number of Black and Latino men were put in jail.

Michael Bloomberg continued Giuliani’s aggressive approach to policing with his controversial “stop and frisk” policy that was found racially discriminatory by a federal court. The billionaire mayor represented a new form of liberalism, or as some would call it, “neoliberalism.” As a philanthropist and mayor, he supported issues like same sex marriage, gun control, and environmental protection – the roots of which could be traced back to the Lindsay administration. Yet, Bloomberg’s embrace of New York as a “luxury item” betrayed assumptions that took root during the fiscal crisis, which held that New York’s survival would depend on attracting wealth and rewarding privilege.

Retention deals filled with tax breaks and other financial incentives for corporations reached new heights of absurdity. Bloomberg also rezoned one-third of the city to make it ripe for development. As a result, many neighborhoods that once provided comfortable homes for working class and poorer people started to disappear as casualties of a gentrification process that displaced long-time residents in favor of those with more wealth.

Bill de Blasio’s election in 2013 marked another turning point. Running on a “Tale of Two Cities” platform, de Blasio was the candidate in 2013 most willing and able to directly confront the Bloomberg legacy. Not since John Lindsay had any candidate taken on the issue of police brutality so directly. More importantly, he opened up a conversation in New York on economic injustice that would distinguish the progressivism of the new century from the old liberalism of the past, and demonstrated that it could win votes. In the meantime, national Democrats like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren had begun a campaign that would eventually move their party off the middle ground it had occupied since the Clinton administration, whose policies contributed to the most severe polarization of wealth in the free world.

Governor Andrew Cuomo did not go along with de Blasio’s plan to finance his signature pre-kindergarten program by raising taxes on the rich, or any of the mayor’s redistributive tax proposals for that matter. De Blasio did ensure an end to “stop and frisk” abuses and worked with a more progressive City Council to pass a number of pro-labor initiatives involving a “living wage” and expanded health benefits.

Although nowhere near peak levels of the 1980s, violent crime is on the rise again in New York and it has taken center stage in the 2021 primary election battle. Tensions with the police remain high in communities of color.

City politics finds itself in a rather odd place these days. Donald Trump is out of the White House and Joe Biden, a seasoned moderate, seems to be taking cues on economic policy from progressives like Senators Sanders and Warren, who Democrats once wrote off as too extreme for comfort. The country may be on the verge of having a new New Deal.

In the meantime, crime and economic development (rebranded as economic recovery) seemed to take over the conversation among candidates for mayor in New York. Little has been heard about the economic justice issues that once helped elect de Blasio. There has been discussion about the urgent need for more affordable housing; but half the eight leading Democrats running for mayor did not support increasing taxes on rich people who have gotten richer during the pandemic.

Did New York ever recuperate from the shock of the 1975 fiscal crisis? Has it lost its progressive soul? When the question is posed to me by my students, my first reaction is to say “No.” If they push me further, I admit I could not continue doing what I do if I did not keep telling myself that. When I think about it further, I return to the essay we read together by John Lewis, published days before his passing, where he explained how the recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations gave him faith in their generation and persuaded him that they can “Redeem the Soul of the Nation.” I hope he is right.

***

Joseph P. Viteritti is the Thomas Hunter Professor of Public Policy at Hunter College. His more recent books on New York include, The Pragmatist: Bill de Blasio’s Quest to Save the Soul of New York and Summer in the City: John Lindsay, New York and the American Dream.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.