As the Economy Worsens: Helping People Find Jobs

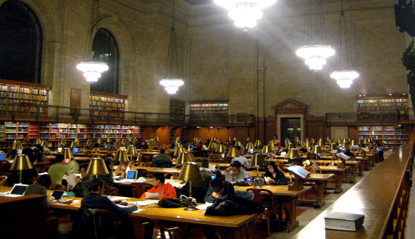

Photo (cc) Becky McCray

As Wall Street does tailspins and foreclosure signs spring up across town, New York City's labor market can seem daunting to all but the best connected. Somehow, though, amid the economic tumult, the city government is helping thousands of New Yorkers find jobs.

That unlikely trend is a product of the workforce-development system, a network of occupational training and counseling services that has historically been seen more as a welfare institution rather than an economic force.

Since 2003, the Bloomberg administration's Department of Small Business Services has sought to transform the system, one of the nation's largest, into a market-based employment network with broad-based training and hiring programs. Under the ambitious restructuring effort, job placements per quarter have grown from about 130 in mid-2004 to some 4,300 by late 2007.

Yet some workforce experts warn that the improvements have not erased structural issues -- from entrenched poverty to limited education to language barriers -- that keep many people out of work. As the system tries to promote job opportunity in underserved communities, it must contend with a dwindling budget and a strained social service system. Reflecting a nationwide trend, the state's workforce programs lost about $130 million in combined federal and state funds between the 2003-2004 and 2005-2006 program years, according to an analysis by the New York Association of Training and Employment Professionals and the New York-based think-tank Center for an Urban Future.

More fundamentally, the system faces the challenge of promoting economic equity while encouraging business growth. Julian Alssid, executive director of the Workforce Strategy Center, an organization that has worked in 22 states to revamp workforce-investment programs, said workforce development should straddle social responsibility and economic interests. "You kind of need to balance the two," he said. "The whole idea of this is you're both getting people out of poverty and growing the economy."

Unemployed in New York

Preliminary reports from the state Labor Department indicate unemployment in the city has eased somewhat in recent years, averaging about 5 percent in 2007. But patterns of joblessness reveal stubborn inequalities. According to 2003 data for the New York metro area, blacks and Latinos had unemployment rates of 12 and 9 percent respectively, compared with about 6 percent for whites. Unemployment among black youth aged 16 to 19 approached one third, compared to around one fifth of white youth.

Meanwhile, the occupations flagged by the Labor Department as having the highest employment prospects range from mechanics and electricians to community service administrators and nurses.

The workforce-development system was built to guide New Yorkers into that hodgepodge of career possibilities. The idea is that by serving as a link between people and the job market, the government can lift up both individual households and the economy's overall health.

Market Logic

Government has often addressed unemployment and business as distinct, even conflicting, policy arenas. But the Department of Small Business Services has sought to recast workforce investment as a business proposition.

"The underpinning of everything that we've done over the last several years was to make sure that any time we are providing workforce-development services, it is in context of very specific jobs that are in demand here in New York City," said Scott Zucker, deputy commissioner for workforce development at Small Business Services.

The city has revamped its Workforce1 Career Centers, one-stop hubs for career and job-preparation services, to place more New Yorkers in "growth occupations" in sectors like health care, retail and food services. The various organizations contracted by the city to run the centers, which are now located in each borough, market themselves as a hiring resource for employers, rather than simply a way-station for the unemployed.

"We want to give the employer a value proposition that says, 'If you work with us, you'll be able to recruit a better candidate than you'll be able to recruit through somewhere else, or doing it on your own," said Tim Ford, executive director of the New York City Employment and Training Coalition, which represents community-based organizations, community colleges and other entities involved in workforce development.

To build ties with businesses, the city has launched NYC Business Solutions Hiring & Training, which identifies and pre-screens job candidates in the Workforce1 system. The program also provides grants to businesses to help fund employee training.

On a smaller scale, the city's "sector-based initiatives," backed by public and private grant money, have launched pilot projects to prepare people for jobs in the biotechnology and medical fields. One program, run by the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, trains people for careers as certified radiology technicians, emergency medical technicians and paramedics.

Much of the growth in jobs through the workforce system has been spurred by big-name corporations, including AOL-Time Warner, FreshDirect and JetBlue. The Atlantic Terminal Mall in Brooklyn has partnered with the Brooklyn Workforce1 center to fill several hundred positions at chain stores like Target and Bath & Body Works, achieving a relatively high rate of successful applications. To take this further, the Workforce Investment Board, an oversight body with appointees from the public and private sectors, plans to establish a comprehensive workforce information service, which would offer current data about the job market and labor force to help employers and community groups track opportunities.

From the service provider's standpoint, Ford said, "it's viewing human capital as equally important as our infrastructure and other pieces of the economic development pie."

Filling Jobs

Yet workforce development's job gains are spread unevenly across the city. People with a basic education and job skills can find work relatively quickly through the system. Others -- like the immigrant with limited English skills or the single mother who reads at the fifth-grade level -- may benefit little from the programs, according to David Fischer, project director for workforce and social policy at the Center for an Urban Future. A recent study by the center found that the Workforce1 system has been able to assist just a small fraction of adults in the city who are unemployed or working poverty-wage jobs.

"If you're not basically employable when you walk into a Workforce1 center, the odds aren't very good that they're going to make you employable," Fischer said, "because the system isn't designed to do that."

While anemic funding is largely to blame, critics say, the problem is complicated by a lack of coordination among the various city agencies tied to workforce programming, such as the Human Resources Administration, which manages welfare services.

The path to "employability" has been slippery for Ketny Jean-Francois, a single mother living in the Bronx. She has been seeking steady work for about two years, but still struggles to scrape by with public assistance and a subsidized apartment.

Jean-Francois said she feels like she's fallen "way, way behind," reluctantly settling into unemployment limbo. "The longer you're on public assistance," she said, "the more you get disconnected from the workplace."

Human Resources' so-called "welfare-to-work" program has required her to take certain jobs to keep her benefits, forcing her to juggle short-term work assignments, child-care responsibilities and long-term goals. The jobs, including an office position at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and work with the sanitation department, have felt more like "serving as free labor" than preparation for real employment, she said.

The program did introduce her to LaGuardia Community College's new Workforce1 center, which offered resume workshops and job-search help. But she said the burden of her work schedule prevented her from taking advantage of those services.

The welfare regime also impeded Jean-Francois's most recent career move: job training in the nursing field. The welfare administration's review of her application for tuition sponsorship dragged on for months. She eventually found a free course on her own, but again had to petition for permission to take classes.

While she is completing her training, time constraints continue to cloud her job prospects. Her young son's subsidized daycare runs from the morning until 5:30 in the afternoon, and many of the positions she has looked into involve night shifts or odd hours.

Now an advocate with the economic-justice group Community Voices Heard, Jean-Francois hopes to forge her own welfare-to-work plan, without interference from the welfare bureaucracy.

"The people that are supposed to be helping you," she said, "they're more trying to keep you where you are."

Left Out

Many youth and immigrants remain far outside the workforce loop.

The Center for an Urban Future's study found a lack of funding for services aimed at so-called "disconnected youth," who are both out of school and jobless. Research shows that young people without work or educational credentials face chronic economic troubles later in life. Yet the center found that career-oriented services have reached only a tiny fraction of the approximately 200,000 youth in need. On top of recent deep funding cuts for youth employment services, the study cited weak coordination between youth workforce programs, managed by the Department of Youth and Community Development, and adult programs under Small Business Services.

Meanwhile, language and culture gaps isolate many immigrants from rapidly growing areas of the economy, according to Pearl Chin, executive director of the Chinatown Manpower Project, which provides training services to immigrants. To match immigrants' needs and abilities, Chinatown Manpower's training tends to concentrate on entry-level jobs in the community -- often small-scale operations with low wages and no benefits.

"A lot of times, we just have to get them in there, just so that they can work and pay the bills and feed their family," Chin said. Now, she added, facing funding cuts and an impending recession, "we cannot even continue to train and place people in those jobs that are so important to their basic survival."

Measuring Progress

So how successful are workforce programs? It depends on how you define success. The federal Workforce Investment Act sets guidelines for evaluating programs based on the number of job placements and employment retention. But critics argue these measures tend to ignore individual progress in terms of career advancement and education.

Chin said the current workforce funding structure hinders service providers from offering immigrants the sustained support they need to move toward self-sufficiency. After they initially graduate from the program, she said, "we want that ability to get them back in and train them in additional skills or English, so that we can place them in a better job, because now they have experience. We don't have the means or the flexibility to offer that additional training."

Reform advocates also want to see tighter coordination within the workforce infrastructure. Currently, agencies serving businesses, welfare recipients and youth all have workforce-related initiatives, but generally operate separately and wrestle with their own budget issues.

The city acknowledges its work is far from finished. Small Business Services is now exploring new performance measures that consider issues such as job quality and advancement opportunities. And the mayor's interagency Center for Economic Opportunity has promised to address structural employment barriers more broadly through social supports and training initiatives.

Alssid of the Workforce Strategy Center said that while the recent reforms are a promising start, the creation of a comprehensive workforce system hinges on whether the next administration can push agencies and community stakeholders to cooperate effectively.

"Ultimately," he said, "what's needed is a negotiation among all of the key actors in the city-the youth-serving agencies, the adult-serving agencies, the community colleges and so on. What can we all do together to really move large numbers of people out of poverty and into family-sustaining careers?"

Â

On the City Budget, Agreeing Not to Disagree

Photo (cc)Wally Gobetz

Libraries, public schools and homeless services will be impacted by the mayor's recent budget proposal.

As national economic conditions continue to worsen, threatening federal and state budgets, prospects for balancing next year's city budget remain surprisingly upbeat. Neither the mayor nor the City Council seems inclined to fight over proposed budget cutbacks or tax decreases.

But some of the negative consequences from Mayor Michael Bloomberg's January financial plan, also known as the preliminary budget, are becoming clear. The Independent Budget Office's March analysis of the January plan and the New York City Council's recent response to it lay out both its immediate good and bad news. At the same time, the council's detailed proposal for a "rainy day fund" shows how the January plan fails to deal with the city's long-term budget problems.

The good news stems, first, from budget office and council projections that the January plan underestimated tax revenues for this fiscal year (2008) and next. The IBO estimates tax revenues this year to be $777 million higher than the mayor projected and $752 million higher in 2009. While not that optimistic, the council still projects higher tax revenues than the mayor -- $258 million this year and $392 million next. The council also has identified other revenues and savings that could provide a total of almost $1.4 billion in new resources.

The higher revenues, plus the use of big budget surpluses from previous years, means budget-balancing this year and next should not be too difficult. In fact, the council is comfortable enough with fiscal prospects to support both the mayor's retention in 2009 of this year's 7 percent cut in property tax and the $400 residential owner property tax rebate -- even though this will cost over $1.3 billion in lost revenues.

But the bad news is two-fold. First, the January plan includes some big service cuts and represents a rather dramatic reversal in such mayoral priority areas as public education, homeless services and libraries. Second, the January plan dodges the longer-term fiscal problems -- the annual deficits of $5 billion to $6 billion or more projected for 2011 and 2012 -- gaps a new mayor and a new council will face.

Across-the-Board Budget Cutting

The bulk of the mayor's budget-balancing for this year and next comes down to across-the-board cuts, 2.5 percent this year, and 5 percent next year. (The mayor's budget director suggested at a recent council hearing that Bloomberg might seek an additional 3 percent across-the-board cut for 2009.) The IBO report has an excellent rundown of what the first round of these cuts means.

In public education -- the mayor's biggest priority -- the plan cuts $180 million in the current fiscal year. Some 63 percent of that will come from individual school budgets. The impact on schools ranges from $10,000 to $447,000 per school, and averages $72,000 per school in 2008. The plan for next year is to cut $324 million, 69 percent of which will come from the schools.

The mayor could have difficulty implementing his cut in another priority area: homeless services. The city's efforts have been disappointing and, as a result, the cost of providing shelter to families has exceeded estimates. In the five years beginning June 2004, the city aimed to reduce the number of homeless families by two thirds. However, according to the IBO, the number of homeless families actually rose by 18 percent from a low in December 2005 to January 2008.

The cost of sheltering these families, projected at $314 million last June, had to be increased by $86 million in January. Although the family shelter population remains at the January level, next year's projected family-shelter costs are again $314 million. (The single adult shelter population reflects better news; it has decreased 23 percent from a high of 8,783 in January 2005 to 6,762 in August 2007.)

In both education and homeless services, the mayor has, more than mid-way through his tenure, shifted policies and administration in major ways not cited in the financial plan, or in the most recent preliminary Mayor's Management Report.

In education, regional administration has been abandoned, leading, the IBO reports, to the elimination of 472 jobs. Much decision-making has shifted to principals; new funding formulas for schools are supposed to give more dollars to more needy schools. The IBO also notes, that recent additional state education funding has been tied to new accountability requirements that the city must meet, such as class size reduction and expansion of pre-kindergarten classes.

In homeless services there are big shifts also, with services for single adults being re-structured and a new rental assistance program created with new rules and expectations. The IBO report is a first step in understanding and monitoring those shifts.

The Council Response: Cuts, Transparency and Reserves

Overall, the council supports the mayor's budget plan. Even in the face of more than $500 million in education cuts over 18 months, the council does not object to the level of cuts but only to their targets. Instead of some of the individual school cuts, the council would reduce the department's $3.17 billion in contracts with outside vendors in 2009, almost 9 percent higher than 2008's total. Bus contracts, for example, are going up over 11 percent a year, and the council urges rebidding of those transportation contracts. Overall, the council proposes a 4 percent across-the-board cut in education department contracts, saving $127 million next year.

The response does include some mild criticism of the mayor's breaking an agreement with the council to minimize friction over repeated over the mayor's repeatedly removing funding for council priority programs, knowing full well the council would restore that funding. The idea was to avoid the annual "budget dance," in which the council each year fights to re-fund favorite programs. Nevertheless, Bloomberg seems to have revived the dance. The council fears, for example, that the mayor will eliminate as much as 60 percent of the funding for six-day library services that was part of the June 2007 agreement.

What may, unfortunately, get lost in the council response is its most detailed and interesting proposal yet to create a rainy day fund, a key to preventing future budget crises. The developing flap uncovered by the New York Post last week over the council's use of non-existent organizations to hide internal budget reserve accounts is (at best) an embarrassment. It would be a shame if the revelations overshadow a fundamental question the council has had the courage to raise: how to create a reserve fund (a rainy day fund) that would become part of the regular budget process, stabilize long-term planning, and make the use of budget surpluses more transparent.

As part of its argument for the new fund, the council has a useful new analysis of recent budget-balancing and how the current use of "rollover surpluses" can distort the city's fiscal condition. Every year since 1981, the city has ended the budget year with a balanced budget as required by state law. Often, though, it has only accomplished this through the use of a previous year surplus to pay for current-year expenses.

If we look simply at current-year revenues and current-year expenditures alone (i.e., "the operating budget"), in 10 of the last 27 years the city spent more than it brought in during the fiscal year, averaging operating deficits of more than $2.6 billion a year. In 17 years there were operating surpluses, some exceeding $4 billion. What the council proposes is a state-legislated reserve fund - a "rainy day fund" - where surplus funds would be put away in good times and from which funds could be drawn in bad times.

When economic conditions improve, the council proposes the city implement a reserve fund that would "equal 12.5 percent of expenditures, thus providing a cushion for the inevitable next cyclical downturn in the city's economy." That would mean a reserve fund of about, say, $7.5 billion with a $60 billion budget, roughly what the 2009 budget will be. The council sees such a fund as giving it an equal role with the mayor in using annual surpluses: "Establishing such a fund would bring these reserves into the regular budget process and result in greater transparency," the budget response states.

The rainy day fund proposal deserves action as well as discussion. Unfortunately, action is unlikely this year. The IBO and council analyses of the mayor's financial plan suggest that both the mayor and council are anxious to keep things simple this year. New tax revenues, across-the-board spending cuts and holding on to tax cuts may well make for a relatively easy budget. The big problem, however, is that there is no commitment by either the mayor or the council to a long-term strategy for budget stability.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Ten Reasons We Don't Have the Economy We Thought We Had

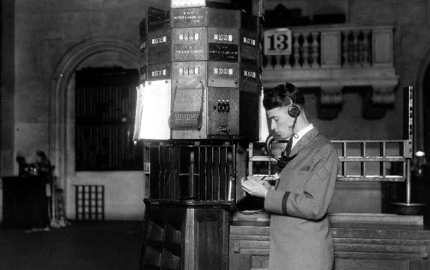

A telephone operator at the New York Stock Exchange, 1928. from the Library of Congress

It makes sense. The news that insurance losses from sub-prime mortgages exceed the losses stemming from Hurricane Katrina gives us an appropriate name for the mess we find ourselves in: an economic Katrina. We always believed that our government would protect us from such a disaster, but boy, were we wrong.

Heeding the call of the current Business Week, "Waking up to the Recession," let's rub the sleep out of our eyes and count the ways today's economy is not the one we thought we had. For this task, the economist in us will need all 10 of our fingers.

1. The Federal Reserve dropped the ball big time.

George Bush's friend "Brownie" (former Federal Emergency Management Agency chief Michael Brown) must have been in charge of the Federal Reserve. Under chairman Alan Greenspan, our nation's "non-political" guardian of the financial system stood by while banks and other lenders jettisoned any sense of prudence and "irrational exuberance" overtook the housing market. The Federal Reserve acted as though it believed that deregulation meant no regulation. Its officials watched in awe while Wall Street bankers developed ever-exotic financial instruments - ABSs, CDOs, CLOs, CDSs and who knows what else - allowing financiers to trade risks back and forth for more fees. These investments built a sub-prime pyramid on a foundation of ever-rising housing prices.

Other "innovative" forms of money-changing proliferated as long as the pyramid went on pyramiding and banks were willing to lend to super-leveraged hedge fund speculators. Whatever we might have expected of "regulators" like the Bush administration's Securities and Exchange Commission, we had thought that the Federal Reserve itself would do financial fire prevention and not just financial fire fighting.

2. Outlandish Wall Street bonuses really aren't good for New York

New Yorkers used to cheer every year that holiday bonuses on Wall Street broke the old record. The conventional wisdom had it that more spending by bankers would slosh around the local economy, and city and state treasuries would be flush with tax receipts to pay for schools, the subway and public hospitals. Now, though, we have learned that big bonus payouts can mean the economy is about to go off a cliff because bankers and brokers do not get those bonuses for helping the American economy create good jobs, new companies or new products. Instead, they rake in those bonuses for finding new ways to generate fees and feed unsustainable speculation.

3. The "You're On Your Own" economy does not apply to giant banks.

In his book, "All Together Now, Common Sense for a Fair Economy," economist Jared Bernstein described how in the YOYO economy, you're on your own to sink or swim. When you fall down or get knocked down, don't expect government to help you get back on your feet. This left millions of middle class workers who lost manufacturing jobs, their health insurance and pensions to fend for themselves. But now we see that if a giant bank (think Bear Stearns) falls on hard times (after its ultra-high stake bets went bad), the government rolls out the plushest safety net you could imagine. It spares no expense -- and does not even ask the bankers who made those bad wagers to return their multi-million dollar emoluments.

4. Credit card debt is no substitute for broad-based wage gains.

Consumer spending drives the U.S. economy, accounting for over two thirds of Gross Domestic Product (the national economic yardstick). Used to be, the economy grew and workers' wages grew, allowing families to put food on the table and a roof over their heads, and still have some money left over to save for vacation, college or retirement. For most workers, wages are no higher today after adjusting for inflation than they were in 2000. To maintain consumption, American families have resorted to trillions of dollars of home equity debt and credit card borrowing. It didn't feel like that would be sustainable for long, and it wasn't.

5. Low unemployment wasn't all good news.

A low unemployment rate once meant that most people had jobs, and if you lost yours, you could find another within a reasonable period of time. That is no longer the case. Now, it means that many people have simply given up. In New York State, for example, enough adult men, particularly black men, dropped out of the labor force in this decade to account for about a percentage point decline in the unemployment rate. They dropped out because the prospects of getting a decent job were almost nil. Also, more of those officially unemployed have been out of work for longer than six months than at the start of previous recessions.

6. Sub-prime lending did not give us record home ownership.

In recent years, economic Panglossians touted what they thought was record home ownership, citing it as proof that a rising tide lifts all boats. Instead, we have had a Tsunami of sub-prime lending. It has created a situation where the equity that American homeowners have in their houses is the lowest since records began being kept in the 1940s, With tens of thousands of mortgage foreclosures already underway or on the way, let's check the homeownership rate in New York City in two or three years.

7. Government spending, it turns out, is pretty useful.

Under the last four presidents, "government spending" usually has been treated like some kind of Evil Empire to oppose or at least rail against. Even the one Democrat among them, Bill Clinton, abandoned his campaign's "Invest in People" agenda that called for expanding infrastructure and other "putting people first" government spending to concentrate on reducing the deficit.

So what happens when the economy suddenly turns south? Politicians embrace a big boost in federal spending to cushion the downturn. This year probably will see another round or two of federal stimulus spending because there's no quick economic rebound in sight. It seems we need government spending after all. And if we had a more thoughtful system of government-funded investment in our physical and social infrastructure , complete with safety nets for people and not just giant banks, our economy wouldn't be so vulnerable to a Wall Street meltdown in the first place.

8: A college education might not get you a good job after all.

"Get a college education, get ahead." That's so "20th century." Now, we know that for most kids who are not from wealthy families, the only thing a college education definitely will get you is a mountain of student loan debt. The global economy is sending millions of white-collar jobs overseas. The Labor Department projects that, even 10 years from now, two thirds of the jobs in our economy will not require a four-year college degree. Since 2002, the real median wage for New York workers with a bachelor's degree or higher fell by 6 percent. Getting a college education is still a good idea, but somebody needs to think about how we get more good jobs in this economy. The challenge is how can policy makers use a combination of carrots and sticks to get businesses to create more demanding and better paying jobs.

9. Having succeeded in keeping wages down, the White House is doing all it can to push prices up.

The Bush administration would not let the 200,000 new employees at the post-9/11 Transportation Security Agency join a union, and it tried to scuttle even minimal labor standards in the Gulf Coast reconstruction effort.

At the same time, though, the administration has made a number of moves sending prices, particularly energy prices, ever higher. It turned over federal energy policy to the oil companies and blocked better fuel efficiency standards. The Iraq war has helped keep the oil-rich Mideast unsettled and oil supplies down, both ingredients for $110 a barrel oil. Its efforts to promote biofuels, like ethanol, have helped push grain prices to record levels. Thanks to this, we have much higher energy and food prices to go along with the recession.

10. Ever-higher trade deficits do matter.

Many Americans have wondered whether importing a lot more than we export really is a good thing if it means that American workers lose their jobs and, as a result, communities across the country lose their people. Nonetheless, as major leaders in both political parties touted the benefits of "free trade," many other Americans thought this was the necessary price to pay for a global economy.

Now more people are beginning to question the free trade faith. Not only did the U.S. lose 3 million manufacturing jobs from 1998 to 2003, but we didn't get any of them back in the recovery from 2003 to 2007 (in fact, we lost almost another million during that "recovery" period). That never happened before.

People see that the sky-high prices they pay at the gas station are going to finance the world's tallest buildings and world-class museums in tiny undemocratic, oil-exporting Mideast kingdoms. People worry about the safety of toys they buy for their kids, the food they feed their pets and the medicine they take themselves. At the same time, the country spends so much more on things we import than the rest of the world spends on U.S. exports that mountains of U.S. dollars are piling up in China and oil-exporting countries. So when Wall Street banks needed fresh infusions of capital to stay afloat, the only places to which they could turn was countries from which we buy our imported oil and manufactured goods. It's no wonder more and more Americans are asking to see (not to mention share in) the benefits from the global economy.

The Wall Street recession (a.k.a. this economic Katrina) may really be a "teaching moment," as they say. It does seem like the economy we thought we had doesn't exist, or at least doesn't exist anymore. At least we should know that when bonuses start to shoot up again on Wall Street, it's time to start worrying.

By the way, it's unofficially official now: The economy is in recession. Not only do 71 percent of the economic forecasters in the Wall Street Journal's survey say that, but economist Martin Feldstein declared it a recession last week. He is one of the handful of members (and the most publicly prominent) of the group at the non-governmental National Bureau of Economic Research that officially makes that call, when they get around to it.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute (www.fiscalpolicy.org). He has been studying and writing about the New York economy since he landed in New York City a quarter century ago.ÂThe Tough Budget Choices Ahead

The Independent Budget Office's annual report, http://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us "Budget Options for New York City," comes along at a useful time. With a near or actual recession unfolding and tax revenues declining, it's pretty clear that big budget troubles lie ahead.

But how far ahead? The good news is that there is time to anticipate the worst scenarios. Revenues will be higher than anticipated, according to Independent Budget Office director Ronnie Lowenstein's recent testimony before City Council. This, she said, not only assures a balanced budget for next year, fiscal 2009, but reduces the estimated 2010 budget deficit to a "relatively modest $2.1 billion," far less than the $4.2 billion deficit projected in the mayor's January financial plan.

This gives Mayor Michael Bloomberg another 21 months to establish his fiscal legacy and, unlike his predecessor, Rudolph Giuliani, leave his successor with a structurally sound financial plan.

So it's the 2011 and 2012 deficits -- estimated by the office to be $4.8 billion and $5.1 billion, respectively -- that remain cause for alarm. The state deputy comptroller for New York City's March report, in fact, says the 2011 and 2012 deficits could be as high as $6.6 billion and $6.1 billion. The big problem, as the city comptroller's March report notes, is that in those years the city will no longer have huge annual budget surpluses from previous years to help balance the next year's budget.

Courses of Action

To confront this, the Independent Budget Office offers a range of options that would save or raise $100 million or more. They fall into three general categories: workforce changes, raising revenues and shifts of fiscal burden from city to state.

Each brings its own political problems: Workforce savings generally mean lower worker wages and/or benefits, as well as more work for public employees; shifting fiscal burdens from city to state requires approval by the state; and tax changes hit influential, higher-income taxpayers. The report takes no position on any of the options; rather, it simply provides arguments for and against each one.

Longer Hours, Lower Pay

Extending work hours and cutting benefits for the city workforce would save nearly $1.1 billion a year in 2011 and 2012. Having city employees work 40 hours a week instead of the 35 or 37.5 hours they're currently on the job, would eliminate 7,000 positions and save $456 million. Requiring workers to pay 10 percent of their health insurance premiums - they now pay nothing - would slash $508 million. A 10 percent reduction in supplemental services (dental, vision, prescription drugs, etc.) would cut another $100 million. All these "savings" would have to be negotiated by the city with the public-sector unions.

These plans might win favor with taxpayers-but would no doubt be strongly opposed by the unions. Two additional options, though, might get many taxpayers angry.

One, estimated at saving $300 million, would institute "pay-as-you-throw" trash collection. Owners and renters would be charged by the volume of their trash, much as they now pay for water and sewer services. Adding two students to all general education classes in city public schools would save $177 million.

Raising the Income Tax

With the exception of the post-9/11 2002 fiscal crisis, which prompted a $3 billion tax increase package, the trend in the city and state for the past decade has been to reduce taxes. So one key option in the report would simply raise the income tax rate on higher income New Yorkers, while still keeping it somewhat below rates in effect from 2003 to 2005 and in most of the 1990s.

The budget office lays out a series of interesting progressive options for the income tax, highlighting how un-progressive it has become. (In a progressive income tax, the higher one's income, the higher the tax rate.) Establishing two new rates above the current top rate of 3.65 percent would raise $619 million in 2012.

The new top rate, for joint filers with $225,000 or more in taxable income, would be 3.92 percent; the second top rate, for joint filers' taxable income over $450,000, would be 4.20 percent. Only 7.8 percent of all city taxpayers would pay more personal income tax under this option.

An alternative would lower rates for those in the lower-income levels as well as raise rates for high earners, with a top rate at 4.20 percent. With this option, which would raise $470 million in 2012, 76.8 percent of all tax filers would get a tax cut in calendar 2009. Both of these options would require state approval.

Then there is the commuter tax, eliminated in 1999 by a Republican governor, a Republican State Senate and a Democratic State Assembly. If restored, that 0.45 percent tax on wages and salaries earned in the city would raise an estimated $835 million in 2012.

The Independent Budget Office report offers a second, more progressive commuter tax option that would raise $470 million in 2012. It would tax commuters' wages in the city at a rate from 0.97 percent to 1.22 percent.

Any commuter tax would require state approval.

Looking at Other Taxes

Several other tax revenue and tax reform ideas would also require state approval. Three property tax options would not only raise up to $400 million a year, but would make the city's property tax system more equitable. One would raise the cap on assessments of houses, which currently gives people who have houses a tax break denied those who live in condos or co-ops.

A second takes away a break for co-op owners. Unlike house and condo owners, they currently do not have to pay a mortgage recording tax when the property changes hands. And a third measure would revise the city's co-op and condo property tax abatement program, which currently favors many owners of high-end apartments.

Compared to personal and property tax options, the options for business contributions to revenue enhancement are quite modest. The three biggest ones would raise a total of about $650 million. These are: imposing the sales tax on capital improvements that are now exempt from it; eliminating the insurance industry's current exemption from the city general corporation tax; and doing away with a cap in the general corporation tax that affects about 44 corporations.

Political Pitfalls

If restoring the commuter tax seems a political stretch, two other options in the report could prove even more problematic.

One would shift city funding of Medicaid to New York State. New York City's share - about $5.8 billion in 2008 -- of Medicaid funding is by far the largest share of any local government in the country. In most states the state covers the non-federal share of Medicaid. Under the plan laid out by the budget office, to offset some of the state's new Medicaid costs, New York City would shift half its sales tax revenue to the state. But the city would still come out ahead, reaping a net savings of over $2 billion a year.

There is some recent precedent for such a swap. The state now picks up any increase beyond 3 percent in annual city Medicaid expenditures and recently assumed the local share of the Family Health Care program. According to the state deputy comptroller's March report, this has saved the city $937 million in 2008 and 2009.

The other hot issue in the report calls for tolling of the East River and Harlem River bridges. To help understand the technical and political questions surrounding this, the Independent Budget Office has a separate "Bridge Tolls: Who Would Pay? And How Much." It envisions one-way-only tolls of $8.30 on the East River bridges, and $3.80 on the Harlem River bridges. If city residents were exempt from paying the tolls, the annual revenue from the fees would dip from $830 million to $376 million. This has been floated in the past but could gain more traction with the mayor's congestion-pricing transportation plan on the political table.

The big-money options in report are not all-inclusive. There are other large tax and workforce actions available, including dropping the current 7 percent property tax cut in the January financial plan, further across-the-board cuts or laying off city workers. That usually is the last step in city fiscal crises, but to take only one example, eliminating 8,000 city jobs with an average $60,000 in wages and benefits would save the city about $500 million a year.

Those are the hard political choices ahead. In real budget decision time, the mayor has less than 15 months to tackle them, not only to keep the city on sound fiscal ground but, not incidentally, to set the Bloomberg fiscal legacy.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

After the Boom: Looking Ahead to Tougher Times

Images courtesy of Stock.Xchng and Evan Raskob

While the exact predictions vary, almost everyone agrees the palmy days of budget surpluses and bulging city coffers are coming to an end. Facing declining revenues, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has said the city needs to trim $1.5 billion from its budget over the next two years. As part of this, he instituted mid-year cuts in the city schools, prompting protests from some students and parents.

The news from Albany could be even grimmer. With 20 percent of the state's tax revenues coming from Wall Street, cutbacks seem inevitable. Already Governor Eliot Spitzer has called for scaling back increases in state aid to city schools. He has proposed some new spending initiatives, but many experts say his budget projections are far too rosy.

It is against this backdrop that the city's 2009 municipal elections are beginning to take shape. Five people - three City Council members, a member of the State Assembly and a borough president - have already announced their intention to run for city comptroller. Whoever wins this election - and succeeds William Thompson, who is term limited (and almost certain to run for mayor) will pay a key role in plotting New York's fiscal future. The city's chief financial officer, the comptroller invests its employee pensions funds, audits city agencies and makes recommendations on city programs and spending.

Gotham Gazette asked the five declared candidates for comptroller to offer their views on what policies New York City should adapt to confront the new fiscal reality.

(Note: Other politicians are considered likely to enter the race. We limited ourselves, however, only to official announced candidates.)

Â

Preparing for the End of the Boom

After five years of booming development and growth, the economy is at a crossroads. The crisis in the housing and credit markets is expected to result in a slowdown in growth nationally this year and in lower city tax revenues and jobs generated by our financial services industry.

If elected city comptroller I will fight for policies that support these goals and manage the city's fiscal affairs so that the maximum resources are available to attain them.

Protecting City Pension Funds

As financial advisor to the city's five pension funds, the city comptroller carries the immense responsibility of producing the best possible investment returns on the $112 billion of assets currently in the funds. The failure to do so not only hurts future payouts to retired city employees but can also increase the city's annual contributions to the funds (which are projected to reach more than $6 billion in each fiscal year from 2009 to 2011). While investment returns have been stellar in recent years, the economic downturn poses a significant hazard to the funds and the city's fiscal health.

Through my role as a trustee of the New York City Employee Retirement System for the last six years, I have become intimately aware of the complex decisions involved in investing in global financial markets and am prepared to take on the role of financial advisor. One of the first actions I would take as comptroller is to direct more staff and resources to this function of the office to meet the challenges posed by current economic conditions. I would also continue and accelerate Comptroller William Thompson's policies of protecting our pension investments through shareholder rights initiatives.

Debt and Infrastructure Policies

The city is facing a debt burden that will increasingly restrict our ability to pay for school, housing and economic development initiatives, and other pressing capital needs. This burden will only intensify in an economic downturn. As comptroller, I will advocate for solutions to this problem that include, among other things, increased "pay-as-you-go" financing and a harder look at what capital projects really need to be financed.

Sound Budget Policies

The current law that allows city budget surpluses to be rolled over only into the next fiscal year and not beyond masks serious imbalances between our revenues and expenses and deprives the city of the chance to salt away money during the good years.

In the bad years, the city has often resorted to "one-shot" infusions of cash that only exacerbate future budget deficits. The city needs authority to establish a rainy-day fund, in addition to the city's retiree health care trust fund, that can be tapped for general expenses during the kind of economic downturn we are about to face. While it is not the function of the comptroller's office to create budget policy, I will work for statutory changes that would allow us to create such a fund and avoid the use of one-shots.

Contract and Program Accountability

The comptroller's power to review and audit city contracts and agencies is essential to ensuring a well-managed, efficient city government. During an economic downturn, it is even more important that the city comptroller require city vendors to deliver what they promise and city agencies to eliminate wasteful spending.

As Bronx borough president, I have led the charge in the development of green, energy-efficient buildings in the borough and will vigorously support the movement to more energy-efficient city facilities. I will also continue Thompson's push to increase the accountability of businesses receiving city tax subsidies from the New York City Industrial Development Authority.

A Housing Crisis

The city comptroller's office also plays a limited, but important role in providing direct services to constituents and weighs in on policies having a major effect on city residents. Of particular concern to me is the sub-prime mortgage debacle and the increasing loss of Mitchell-Lama housing in the city. In the Bronx, I have been leading an effort to better coordinate information and services among the various institutions that provide assistance to Bronx homeowners unable to make the payments on their sub-prime mortgages.

As comptroller, assisting homeowners to keep their homes will be a top priority. I will use the bully pulpit to demand that the federal, state and city governments expand their housing programs in the city and create new financing options that help city residents remain homeowners.

I believe that by addressing these issues we can continue to grow a stronger economy and improve the lives of all New Yorkers.

Adolfo CarriĂłn, a Democrat, has served as Bronx borough president since 2002.

Â

Three Steps to Keep the City's Economy Moving

With a sluggish national economy and recession looming, New York City faces a potentially perilous economic future. Because of this, next year's election is so important. While the media's attention will be largely focused on the race for mayor, it is the position of comptroller that can have the most direct impact on the strength of city finances for years to come.

The authority of the office, which includes the power to audit city agencies as well as investment oversight of the $106 billion pension fund, brings with it an immense amount of responsibility. The next comptroller will play a critical role in protecting the solvency and economic vitality of our City.

The situation confronting the next comptroller will depend in large part on the duration and depth of the looming recession. It will take bold vision and creativity to lessen the financial impact on the city and get the engines of our economy moving again. As comptroller, I will push for a three-pronged strategy to: maintain our core tax base, streamline government services to tighten spending and invest in the future.

Keeping Our Tax Base

When New York has faced financial crises in the past, we have seen our core taxpayers -- working families -- driven from the city. No new spending program or bold initiative will be possible if we lose our working families, the heart of New York City. A New York without public school teachers, police officers, firefighters or sanitation workers is not what we want to become. If we are to remain a viable, dynamic, thriving city, we must protect our urban middle class.

As I travel throughout the city, the number one question I am asked is how the sub-prime housing crisis will affect New York. Current trends in the real estate market suggest that Manhattan should remain safe for now, but we need to protect ourselves. It is the residents of the four boroughs outside Manhattan, where most of New York's working families live, who are most vulnerable

The crisis already has had a direct impact on many New Yorkers, from families losing their homes to financing for larger commercial projects proving much more difficult. Nationwide, the domino effect from the sub-prime fiasco is spreading from banks to credit markets to bond insurers to municipal bond ratings, which could devastate the entire financial services industry.

The first step in addressing the concerns of working families is to assist New Yorkers in weathering this. While homeowners throughout the country will need substantial assistance at the federal level, New York can work quickly with major banks and lenders to shore up the housing market here by guaranteeing portions of existing mortgages in exchange for extensions in favorable introductory rates. This will help settle the New York real estate market and send a clear message to affected residents that our city is fighting for them.

Because public education is the cornerstone of the urban middle class, the second key component of keeping our tax base is through a strong public school system. While the jury is still out on many of the Bloomberg administration's education reforms, thanks to the hard work of our teachers and principals, we are seeing signs of progress. In difficult budgetary times, the classroom must remain one of the last places where we cut funding. Instead, we should focus any funding reductions on the Department of Education itself.

Streamlining Service

City government must tighten its belt and evaluate how government services can be provided more efficiently. The first step for the next comptroller will be to use the audit authority of the office to make sure our money is being spent wisely. Comptroller William Thompson has focused on auditing city agencies and making them work more efficiently, a practice that the next comptroller should continue as the city's fiscal watchdog.

In building on these efforts, the comptroller should not only use this authority to streamline city agencies, such as the Department of Education or the Department of Buildings, but also act as an advocate for New York City with Albany. For example, with recent questions on fare hikes and wasteful spending, it is clear that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority needs to be examined regarding providing for fairer treatment to New York City residents. I pledge to fight for the interests of New York City to ensure that every dollar we send to Albany is well spent.

Moving Forward

With our tax base shored up and our budgetary belts tightened, we must work to get the engines of the city economy moving again. The next comptroller should think creatively on how to take advantage of certain economic challenges to turn them to our advantage. For example, the weak dollar abroad has made New York an attractive option for foreign investment. As residents of the financial capital of the world, New Yorkers should embrace globalism and encourage foreign investment to capitalize on the weakened dollar. Americans have sent enough of our jobs overseas. Let's get some of that global investment back and use it to put New Yorkers to work.

While we work to keep New York at the forefront of the global economy, we have to take steps to encourage businesses to remain and grow in the city. An easy first step would be to eliminate the city sales tax, an immediate boost to the retail economy. In addition, the city must develop initiatives for new businesses to move to New York, employ our residents and pay wages that will not only employ but also train workers for advancement.

As Wall Street cools off and construction slows down throughout the city, forward-looking government leaders would be wise to invest in long-term infrastructure projects. These public works projects will keep the momentum of the economy going and keep workers employed. It could also be smart shopping, taking advantage of reductions in construction costs due to slowing commercial activity. Should the private sector slow down due to financing difficulties, opportunity will be ripe for the city to take advantage of lower costs and frontload needed capital projects. This will jumpstart portions of the economy, keep people working and be more cost-efficient in the long run. As a much-needed result, these capital projects -- improved roads and bridges, upgraded sewers and new schools -- will help build a better-running city.

While our City may face a difficult road ahead, New Yorkers have always met challenging times with the strength and perseverance that define who we are. I entered public service more than a decade ago because I wanted to be part of building the future of the City I grew up in and love. I have been so humbled in serving the people of my district in the Assembly, on the City Council, and all of New York as Chair of the Land Use Committee. As we confront this next set of challenges, I hope to be part of building a New York that we can all be proud of as the next Comptroller of New York City.

Melinda Katz, a Queens Democrat, has served on the City Council since 2002 and heads the Land Use Committee.

Â

How to Deal with Declining Revenues

The past several months have been chaotic for most municipal economies in the nation, New York City included. And Mayor Michael Bloomberg's preliminary budget reflects this worsening economic picture. I believe the single biggest challenge facing New York City in 2008 is how to maintain current spending demands on less tax revenue - the fuel that keeps the furnace burning.

There are two issues that severely threaten our revenues, both of which I discuss often as chair of the City Council's Finance Committee. The first is the risks to Wall Street profitability, something most other cities need to worry about only tangentially. Despite starting off 2007 on a strong note - Office of Management and Budget reports that New York Stock Exchange member firms gained more than $8 billion in profits in the first two quarters - the credit crisis that developed over the summer has weakened portfolios.

New York City relies so much on Wall Street profits primarily because it greatly impacts the taxes we collect on income, including bonuses, and on employment generally.

Although bonuses are expected to remain rather steady due to strong performances in early 2007 and strength in sectors unrelated to the credit crunch, we expect an overall drop in financial sector wages. Additionally, the budget office reports that several financial firms have announced or are likely to announce layoffs and reduced staffing, leading to an expectation that financial sector employment will shrink by about 12,000.

The Housing Crunch

The second major risk to the city's revenues is the declining local real estate market. Although this past year the local housing market has been stronger than that of most cities, consumer confidence, lower overall employment and other factors have increased housing supply.

The Office of Management and Budget estimates that single-family home sales will drop about 20 percent in 2008 and that co-op and condo sales, which reached an all time high this past year, will fall measurably.

So with the decline in the city's finances, led by Wall Street instability and a worsening housing market, what can Bloomberg do to steer the city clear of the economic downturn? What wisdom can I or anyone else recommend to stem the downward slide? The answer to both questions is: not much.

A Sneeze to Turn Into A Cold

The plain truth is the city's economy is not exempt from a law of economics: For every up, there is a down. The other plain truth is that mayors have no real control over the duration of these economic cycles.

One of the few things mayors can do, and what Bloomberg is already doing, is working to limit how deeply the city feels the effects of the downturn. This is principally done by tightening spending to maintain a balanced budget. Bloomberg has reduced city spending in the current fiscal year and in the next. I'm not happy with all the cuts, and I've vowed to fight the most unpalatable ones. These include cuts made to the Runaway and Homeless Youth program, geriatric mental health and the Autism Initiative, a $1.5 million program I created last year that lends educational and emotional support to affected children.

Another of the few things mayors can do, particularly during a recession, is, of course, raise taxes to make up for revenue shortfalls. Bloomberg did this by way of raising property taxes during the 2001 recession. None of us at City Hall want to do that this time around.

It remains to be seen how much worse the economic scenario gets before this option becomes a viable idea. Just as Bloomberg has said, the next few months will shed light on the many tough decisions ahead. In the meantime, I've said often that a tax increase is on the table only as a last resort.

Not Looming, But Here

So, you'll notice I've used the "R" word. Some cities have already been claimed by recession. Many analysts say Detroit, with its rate of housing foreclosures in the double digits and its high unemployment, is already in recession. San Francisco, Cleveland, and Miami are a few others being watched closely for symptoms of acute recession. Is New York City soon to join the list? The city is in an economic downturn, to be sure, but based on the current data, I don't think we'll fall into actual recession.

We might be lucky this time. One of the many things I've advocated for at the City Council is to use our surpluses in the smartest manner possible. Pre-paying some of our obligations, including placing $2 billion aside for retiree health expenses, when we had surpluses has proved helpful to us now.

Amid the doom and gloom there are some economic bright spots for the city -- including that our tourism industry is booming. We can thank our superb attractions and the weak dollar for that. NYC & Co., the city's tourism agency, predicts that the city welcomed a record 46 million tourists, many of them international visitors, in 2007. And all signs continue to point to similar tourism rates over the next couple of years.

A strong tourism industry plays a vital role in sustaining the city through the lean times, because it keeps hotel taxes, sales taxes and employment humming. There are also some sectors of the economy that continue to grow regardless of the current economic cycle. Demand and employment in both the education sector and health services sector remains strong.

The Comptroller's Role

Is there any role to be played by the city's next comptroller in ameliorating the effects of the ongoing downturn? The office of the comptroller is involved in the issuance of General Obligation bonds, setting the terms and conditions for all debt, analyzing contracts and auditing programs and agencies, and is the investment advisor and custodian of the city's pension funds. Within each of these responsibilities and in varying degrees the comptroller can join the mayor to also limit the effects of the downturn. Scrutinizing spending is one responsibility the comptroller can implement rather swiftly. I already do that in my role as chair of the City Council's Finance Committee.

Apart from official functions of the city's comptroller, there is a more nuanced yet potent function. As the finance specialist for the city, the comptroller is in an excellent position to advocate fiscal policy that would cushion the blow of economic downturns. One such policy I've consistently called for is the creation of a Rainy Day Fund, which requires state legislation. This savings account would be funded over a period of years with budget surpluses to aid the city during lean times.

A Rainy Day Fund would not only cushion services during downturns, but, assuming it would replace the current practice of rolling prior year surpluses into the next, it would also make the city adopt a budget that more accurately reflects our current financial status. Additionally, the comptroller can use his or her position to advocate for reduced reliance on non-recurring revenues to balance the budget, something that has occurred too often and will be untenable in coming years.

The final analysis for comptroller ought not rest on what he or she can do during tough times, because the official tools at his or her disposal are very limited. Rather, the analysis ought to rest on what skills the current and future comptroller possesses in order to understand and deftly manage the effects of economic downturns. As someone who has spent more than 20 years on and off Wall Street as an expert in municipal finance and who has served as chairman of the City Council's Finance Committee, I will bring to the comptroller's office a host of related experience.

David Weprin, a Queens Democrat, has served on City Council since 2002 and chairs the Finance Committee.

Â

Changing the Way the City Does Business

New York City is facing some tough economic times.

Everyone knows the basics by now: Foreclosures are way up; Wall Street has already begun layoffs, with more to come; and the debt crisis is not only roiling the financial markets, but is starting to affect the city's cost of borrowing. Virtually all economic analysts agree that in the near and medium-term, current forecasts for growth and revenue are likely to prove optimistic -- all the risk is on the downside.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's preliminary budget issued in January reflects these realities and prudently begins to adjust for the slump. But the real task for those of us who lead the city government is to take our current difficulties as an opportunity for much deeper rethinking of our budget policies.

There are many avenues to pursue, but I want to highlight five priorities: rooting out wasteful spending, eliminating corporate welfare, reforming the budget process, diversifying the city's economy and making our tax code fairer.

Cracking Down on Spending

We must be far more aggressive in reducing spending on programs that don't achieve their stated goals or that do so inefficiently. For example, I recently went after a poorly designed affordable housing program called "HomeWorks/StoreWorks," which cost the city more than $500,000 per apartment. After publicity exposed this boondoggle, the department of housing preservation and development terminated the program.

Sometimes government costs are inflated not just by inefficiency, but by actual fraud. To crack down on this, the City Council in 2005 passed a bill I authored called the "False Claims Act" that allows whistleblowers to initiate suits against contractors who have been ripping off the government. The bill was modeled on a successful federal statute that has been used to recoup funds from fraudulent defense contractors and health maintenance organizations. Unfortunately, the city's Law Department insisted on watering down the bill with a provision allowing the department to block the whistle blower suits-and the department has abused this authority by blocking every single suit initiated so far. The City Council's Finance Division estimates that, if properly implemented, the bill would save taxpayers $30 million a year. We should go back and reinstate the original, stronger bill.

Ending Corporate Tax Loopholes

We should also eliminate corporate welfare. Last year, I joined with Councilmembers Annabel Palma, Letitia James and others to repeal a loophole that allowed developers to put up new luxury buildings and pay no property taxes on them - the so called "421-a" law. That reform will bring in at least $500 million dollars over the next five years. The next step is to reform the Industrial and Commercial Incentive Program, a similar loophole for commercial development.

Of course, the single biggest example of corporate welfare is the proposed Atlantic Yards development. The Bloomberg administration has agreed to give the project's developer at least $100 million in direct subsidies, plus another $400 million to $500 million in tax breaks. In the current financial climate, this handout is impossible to justify.

Reforming the Budget Process

Beyond tightening spending and eliminating unnecessary tax handouts, we should also reform the budget process itself. City Council Speaker Christine Quinn has made great strides toward a more transparent budget, and we can build on her accomplishments.

We must break down the budget into specific spending items for each individual program, rather than grouping things in big lump sums, called initiatives. We should also end the practice of negotiating budgets behind the scenes and then simply holding an up-or-down-vote at the end of the day. Instead, each City Council committee should vote on the budget for the agency in its jurisdiction-and the committees should be permitted to add new spending only if they find offsetting cuts.

A More Varied Economy

We need to renew our focus on diversifying the city's economy. Turmoil in the financial markets only underscores how dependent we are on banks and investment firms. The financial sector will and should remain the heart of our economy, but city policy should be directed at helping other sectors grow as well. Our highly successful film production tax credit is a good example of an initiative that has created good-paying jobs for skilled and semi-skilled workers outside of Wall Street.

Another, similar opportunity is shipping. Instead of trying to squeeze out the city's remaining container ports, as the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey has misguidedly done, we should help them expand.

Taxing Income

Another urgent priority is to make the city's income tax fairer. The current downturn is hitting low-income families the hardest, and our first impulse should be to ease the pain. One concrete and immensely useful step would be to give tax relief to the city's working poor.

Astonishingly, more than 600,000 New Yorkers live in households that are too poor to pay any federal or state income taxes - but are nonetheless required to pay the New York City income tax. This is mostly due to the fact that the federal and state tax laws provide a far more robust Earned Income Tax Credit than does the city tax code. The Earned Income Tax Credit is one of the best innovations of progressive government - it rewards those who, in President Bill Clinton's words, "work hard and play by the rules." We should beef up the city's tax credit to put much-needed dollars into the hands of the city's working families.

The boom of the past few years has been good for the city, and we all wish it had continued. But it also allowed us to defer some difficult choices. In this, more challenging period we will have no option but to confront our structural budget problems.

With innovative and decisive leadership, we cannot just slog through the fiscal slump, but we can thrive despite it.

David Yassky, a Brooklyn Democrat, has served on City Council since 2002 and chairs the Small Business Committee.

Â

Bringing Insurance to Small Business

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn endorsed the creation of a citywide ferry service and an expansion of a small business insurance program in her State of the City address last week. Now advocates and stakeholders are weighing in, and - for the most part - appear to be praising the proposals.

At Cartridge World, a downtown Brooklyn firm that sells new and refurbished cartridges for photocopiers, printers and fax machines, the cost of health insurance for owner Geoff Wood’s three employees seemed sure t empty his pockets. When Wood initially looked into comprehensive health insurance plans, they exceeded $500 per employee per month.

Thanks to a health insurance program created for Kings County businesses by the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, Wood was able to get more affordable coverage for his employees, saving him more than 50 percent in premium costs. This made his employees not only happier, but healthier. According to Wood, his employees “were less likely to leave because they had good health benefits.” For Cartridge World this translates into increased employee satisfaction and higher productivity.

In a recent survey conducted by the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, an overwhelming majority of small businesses support universal healthcare and want to offer coverage to their employees.

The problem for owners like Wood and other Kings County businesses is that it can often be difficult to afford. But Brooklyn HealthWorks, the insurance program founded by the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, can provide an interim solution as the nation debates how we can cover more workers - whether through mandates or a free-market based system or a combination thereof.

And soon, small businesses in other boroughs will be able to reap the benefits, including attracting and retaining qualified employees.

Beyond Brooklyn

Last week in her annual State of the City Address, City Council Speaker Christine Quinn proposed an expansion of Brooklyn HealthWorks into Manhattan and Queens. Quinn’s speech balanced a call for continued fiscal responsibility with initiatives to stimulate the local economy, protect affordability and support New Yorkers.

Under the speaker’s plan, the city would subsidize premiums for businesses in Queens and Manhattan. Based on Brooklyn’s experience with HealthWorks, upward of 600 new businesses are expected to enroll in Manhattan and as many as 300 businesses will enroll in Queens during the first year alone. This equals an additional 4,500 New Yorkers with employer-based coverage. Citywide expansion is expected to follow and will further increase the number of New Yorkers with health insurance coverage. Since Quinn’s address, Brooklyn HealthWorks has received inquiries from small business owners and brokers in Manhattan and Queens - all looking to learn more.

A History of Health

In 2004, with the help of the New York State Insurance Department, the chamber created Brooklyn HealthWorks, a private-label Healthy NY insurance product. Brooklyn HealthWorks allows eligible small businesses in Brooklyn to offer affordable health coverage to their employees and dependents at lower premium rates than other small group plans because of premium subsidies made available by the state. Brooklyn HealthWorks currently covers approximately 180 small businesses, including more than 850 employees and their dependents.

Brooklyn HealthWorks builds on the success of Healthy NY by offering a plan that eliminates hospital co-payments that run between $500 and $900 per occurrence for Healthy NY plans. Brooklyn HealthWorks also does not dictate how much an employer must contribute to premiums. For Healthy NY, businesses are required to contribute at least 50 percent of the cost of individual coverage. Finally, Brooklyn HealthWorks provides coverage to independent contractors (1099 employees) who work at least 20 hours per week at small businesses that also cover traditional (W-2) workers.

The same eligibility requirements will apply for an expanded HealthWorks program: A business must have a location in the participating borough with 2 to 50 employees and have not provided comprehensive health coverage during the last year (or have contributed less than $75 per employee per month). Additionally, 30 percent of the company’s employees seeking coverage must earn $36,500 or less annually. For businesses that qualify, healthcare savings can be reinvested into employee training programs, promotion and the creation of new partnerships with other local businesses—all of which stimulates economic growth.

HealthWorks operates in partnership with Group Health Incorporated. Businesses with access to HealthWorks coverage are able to obtain care at over 142,000 provider locations throughout the tri-state area, all without the need for a referral. Some of the benefits included in the plan are physician services, hospitalization, prescription drug coverage up to $3,000 annually, maternity care, emergency services, and diagnostic X-ray and laboratory services.

The Brooklyn-based program has changed and grown over the years, but because of permanent funding streams – secured with the assistance of Brooklyn legislative leaders such as Assemblymember Joseph Lentol and Senator Martin Golden – it continues to flourish. We are confident HealthWorks will continue to address the affordability of healthcare for small businesses in Brooklyn and beyond.

Carl Hum is president and chief executive officer of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce. Â

Tax Breaks - Who Wins and Who Loses?

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's January Financial Plan for the next four fiscal years repeats the message of last October's budget modification: The economy is slowing, city tax revenues are down, and it's time to make budget cuts. The mayor balances the preliminary $58.5 billion budget for 2009 through agency spending cuts over the next 18 months and the use of surplus funds from last year. The four-year plan, however, projects deficits of $5.6 billion in 2011 and $5.3 billion in 2012.

Excessive cuts for commercial interests seem to have caught the attention of the City Council, if only in its recent near-unanimous vote to end the 25-year-old property tax exemption held by Madison Square Garden (a vote that is meaningless unless the state legislature and governor also act). Testimony at the council on the garden's tax break also called attention to much larger commercial tax breaks that also could use council review.

A variety of tax cuts and breaks - including the $400 property tax rebate - cost the city revenues. With no significant service initiatives or increases in the preliminary budget for 2009 - and education cuts that look like a major retreat from an earlier mayoral priority - it's a good time to look a little more closely at city tax breaks in general. Who wins, who loses, and what are the costs?

Billions of Breaks

The city's recently updated Tax Expenditure Report for fiscal year 2007 provides a useful window into the billions of dollars in city tax breaks - commercial and residential property taxes in particular.

Many seem likely to remain during the widely predicted economic downturn. The mayor's financial plan extends the big property tax cuts in the current fiscal year through all four years. Next year's property tax cuts -- the $400 rebate for homeowners and a 7 percent property tax rate cut -- will cost over $1.3 billion in lost revenues. This almost dollar-for-dollar underwriting of tax cuts with agency cuts in 2009 will presumably be controversial at the City Council, setting the stage for the annual "budget dance," in which the mayor diverts the council from larger issues by slashing council initiatives, which the council then fights to restore.

The city took in about $13 billion in property taxes in 2007. All the individual property tax breaks add up to $3.3 billion in lost revenues. This does not include the 7 percent rate cut, but does include the $256 million cost of the homeowner rebate, the $311 million property tax abatement for co-op/condo owners (a 1996 "temporary" council plan to narrow the property tax burden between those owners and house owners that keeps getting extended).

Business income and excise tax breaks added another $573 million in lost revenues (in 2004). The largest of these remains the $248 million that insurance companies saved because they do not have to pay any city business income tax.

Commercial Tax Breaks

At the January 7 City Council hearing on ending the Madison Square Garden $12 million property tax exemption - granted in 1982 when the Knicks and Rangers threatened to leave the city - Bettina Damiani, director of GoodJobs New York, an advocacy organization, asked the council to review much larger questions of tax expenditures (a technical term for tax breaks) granted by the city's Industrial and Commercial Initiative Program.

The tax expenditure report notes that 5,771 exemptions and abatements under this pogram cost $410 million in lost revenues in 2007. Good Jobs New York argues that the initiative program, which was intended to help small firms outside the core Manhattan commercial district now includes benefits for "some of the priciest commercial districts in the city," including $14 million in tax breaks in 2007 for properties in mid-town Manhattan.

These tax breaks rarely get any review. The 2007 tax expenditure report does not feature any independent comment by the Department of Finance, which publishes the report, and offers only a single "evaluation" of business tax breaks. That's a one-page summary provided by the mayor's Economic Development Corporation of its Local Law 48 report for 2006, which is supposed to track the costs and benefits of the development corporation's tax exemptions. This mini report makes two extraordinary claims.