The City Modifies Its Budget and Searches for Cash

Every year around this time, the city charter requires the mayor to update the budget, called a budget modification. It was during last year’s modification that Mayor Michael Bloomberg unveiled an 18.5 percent increase in property taxes. This year, there is nothing so dramatic.

The good news is that the modification suggests at least a slight improvement in the city’s economy; it includes nearly $500 million more in projected non-property tax revenues. This news is supported by the City Comptroller’s December economic reportthat says, “The city is showing clear signs of economic recovery.” The city still lags behind the national recovery, and job losses continue, but the gross city product grew in the third quarter of calendar 2003 by 0.3 percent, after 10 quarters of decline.

The sobering news is that even after a $3.4 billion increase in tax revenues this year, revenues will be nearly $1.9 billion short as early as next year, and there is a projected budget deficit for 2007 of nearly $3.9 billion.

And so, there is a new search for new revenue once again.

THE 2004 MODIFICATION

This year’s budget, only five months old, jumps to $45 billion, some $1.3 billion more than projected in late June. In addition to the $500 million increase in non-property tax revenue projections, the modification recognizes federal and state categorical grants of another $600 million. Since they are given for specific purposes, these grants generally do not help in reducing budget deficits.

The city will use most of its new revenues in two ways: The budget stabilization account – a reserve fund where the city can park dollars – gets over $400 million (which at least in the current long-term plan will be used to reduce the budget deficits in the next two years). This is in addition to $300 million already in the general reserve fund, for a projected year-end surplus of over $700 million. Another $200 million will be used this year as pay-as-you-go capital expenditures. This has the advantage of reducing capital borrowing and thus reducing interest payments. The mayor plans to repeat this annual expenditure in the three subsequent years.

Total salary, wage, pension, and fringe-benefit costs of the city workforce are up a little over $200 million, to $24 billion, while other-than-personal service projected costs (including Medicaid, public assistance, and contractual human services) are up about $500 million since June, to nearly $19 billion. These modest changes seem again, at least in broad terms, to support the mayor’s claim that he has been able to keep services stable.

BEYOND THE 2004 BUDGET

The mayor and the City Council created a good part of future budget shortfalls by making this year’s increases in personal income and sales tax only temporary.

The mayor’s tax revenue strategy last year was bold but sudden, effective but undemocratic. Both the property tax increase in November 2002 and the personal income and sales tax increases in June 2003 were last-minute proposals that made public (and city council) engagement impossible. Thus it is no surprise that this November modification contains no information about future strategies.

Tolls On Bridges

The mayor’s first ambitious revenue idea – the introduction of tolls on the city’s bridges – was floated in the early months of his administration. Strong opposition to that idea and his current reluctance to follow-up perhaps help explain the secret revenue planning since. But the Independent Budget Office’s October 2003 report, “Bridge Tolls: Who Would Pay? And How Much?” is a good reminder of how important those revenues could be to attaining structural balance in the city’s long-term financial plan. The IBO estimates that the city could raise nearly $700 million a year by tolling the East River and Harlem River bridges.

One big objection to tolling bridges, of course, is that a majority of the drivers (55 percent) are New York City residents. The report speaks to that worry by noting (in an admittedly rough estimate, based on a household survey), “Exempting city residents from tolls would reduce the annual revenues to a combined $308 million.”

In terms of numbers of users, the report shows that fewer than 300,000 New Yorkers (out of 8 million) drive across these bridges, about 3.7 trips per 100 residents. In terms of income, about 42 percent of all users of the bridges are either low to moderate-income city residents (under $50,000 household) or middle-income city residents ($50,000 to $100,000). The report points out that although the number of New Yorkers affected would be few (and some would take alternative mass transit), the impact would be much more concentrated than in the case of personal income and sales taxes.

Stock Transfer Tax

Another IBO study, “Reviving the New York Stock Transfer Tax: Revenues and Risks,” speaks to another big revenue option that has been proposed by some advocacy organizations, including the Working Families Party and the Fiscal Policy Institute. The city first imposed a stock transfer tax in 1966. It was phased out by 1981. If still in place, it would have produced $9.3 billion in 2003 for the city. The study traces the impact of reviving the tax, at half its 1970s’ rate. That would produce nearly $5 billion, if there were no “adverse reactions.”

In a best-case scenario, the study finds that the new tax would increase transaction costs by 23 percent, reducing trading volume on the New York and American stock exchanges by 18 percent. That would eliminate nearly 60,000 private-sector jobs. Since the increased revenue would fund almost 38,000 public-sector jobs, the net job loss would be 22,000. That translates into a net revenue gain of $2.9 billion for the city. The study concludes with another scenario with “significant downside risks” – where one-third of trading activity moves out of the city – and job losses in the city “could climb to 150,000 and net city revenue gains would fall to zero.”

One-Shot Deals – 1. Airport Lease Agreement

Given the imminent reduction in basic tax rates and a reluctance to tackle controversial revenue sources like the city bridges and Wall Street, the mayor has become more dependent on one-shot deal-making. The apparent long-delayed agreement on a new airport lease agreement between the Port Authority -- announced by Governor Pataki and Mayor Bloomberg in October -- is the prime example. It is worth $700 million in up-front money over the next two years, and nearly $100 million a year thereafter.

While there seems to be general acceptance among fiscal monitors of this deal (former Mayor Rudy Giuliani failed during his two terms to settle disagreement over Port Authority payments to the city under the old agreement), a deal that ties the city until 2050 has received surprisingly little public attention or review. The deal is nevertheless a key to the current four-year financial plan.

One-Shot Deals – 2. Borrowing-for-Cash With Battery Park City Authority

Another quiet deal built into the current fiscal year budget is the city’s agreement with the Battery Park City Authority, controlled by the governor, to borrow $150 million through the authority, primarily to provide cash to the city. This requires state legislative approval and mimics a similar borrowing-for-cash that former Mayor David Dinkins employed through the authority in the early 1990s when in a fiscal bind. In both cases, the city in effect pays the debt service, through reductions in excess Battery Park City revenues that would otherwise come to the city. (A related if forgotten story is that excess authority revenues were supposed to be used for affordable housing.)

One-Shot Deals – 3. Snapple

The mayor has now moved from behind-the-scenes, public-authority deal-making for cash to corporate/city deals. The mayor’s agreement with Snapple to provide certain beverages to the public schools and other city facilities has roused the opposition of both the City Comptrollerand the City Council, which held a long hearing on the deal on December 4. The Comptroller, who testified at the hearing, objects to the process, and several Council members objected both to the process and the substance of the Snapple agreements described by Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff.

The Comptroller, in his remarks, said that the city “can’t cut corners” and “must be above reproach” in the procurement process. Doctoroff later contended that the deal was not subject to city procurement rules, that it was a unique opportunity for the city to develop a profitable relationship with a brand-friendly company. Several representatives from other beverage companies charged that the competitive process was flawed and at least two said had they known the full potential of the deal, they would have bid more than Snapple.

The $166 million in anticipated revenues over five years is not insignificant, but as council member Bill Perkins pointed out, there are potential problems with “monopolistic opportunities” and using “kids as captives.” No one at the hearing asked how many water fountains there are in schools. After all, the deal, among other products, promotes bottled water for the students; thirty percent of the student cost for each bottle goes to the city. (Well, not quite. Actually, fifteen percent of the city’s share of that payment goes to Octagon, the private marketing firm that negotiated the Snapple deal for the city.)

It’s good to know that our children will be making their contribution to the city’s balanced budget.

Glenn Pasanen, former associate director of City Project, teaches political science at Lehman College of the City University.

Carbon Monoxide, The Silent Killer

When James Tyrrell dreams of a white Christmas, it isn't your usual Bing Crosby, Currier & Ives fantasy.

Director of the Jacobi Medical Center's Hyperbaric and Underseas Medicine unit, New York City's primary treatment center for carbon monoxide poisoning and smoke inhalation, Tyrrell knows firsthand what a nightmare the year's first major snowstorm can be.

"Last year, at one point, we counted 26 patients for carbon monoxide poisoning within a single 24 hour period," he says.

How so many patients ended up in the Bronx hospital's submarine-shaped pressure chamber is, of course, the real nightmare. Unlike lead, asbestos, and radon -- much-publicized household toxins that do their damage primarily through long term exposure -- carbon monoxide needs only a few minutes to ambush its victims. Odorless and colorless, it is a stealth killer that avoids the environmental and public health spotlight almost as easily as it evades the eyes and nostrils.

When carbon monoxide does finally make an appearance, however, the results tend to be cringe-inducing.

For New York City residents, the first cringe of the winter season came early this year. On Nov. 21 Bronx firefighters responding to an emergency call in the Morris Heights section made a grim discovery. When they got to the house of Patrick Williams, 26, they found Williams, his two month old daughter Patricia and his 54 year-old mother Erna Dennis all lying dead, victims of suffocation. According to a Daily News story filed the next day, the family's electric service had been cut off by Con Ed for nonpayment, and the family was relying on a gasoline-powered electric generator for power. Fire crew found the generator, sitting idle with an empty tank, in an attached garage.

Noting the lack of a carbon monoxide detector in the house, New York Fire Department inspectors have little doubt that the improperly ventilated generator and its resulting fumes were the chief culprit behind the deaths, says Battalion Chief John Salka, commanding officer of the responding fire units.

"If you don't have a smoke detector, there's a small chance you might smell the smoke in time," says Salka. "If you don't have a carbon monoxide detector, your chances of smelling carbon monoxide fumes in time are literally zero."

According to an August, 2002 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Assocation, carbon monoxide suffocation accounts for 2,000 American deaths each year. Local totals are hard to come by, but Dr. Michael Touger, a specialist at the same hyperbaric unit, says his facility treats the most severe carbon monoxide-related cases in the metropolitan area and handles up to 150 emergencies each year.

Many of those emergencies, including the Nov. 21 Bronx emergency that sent a surviving family member to Jacobi Medical Center's hyperbaric chamber, could have been easily avoided with the help of a home carbon monoxide detector. Unfortunately, getting those detectors into homes has been a slow-going process.

Ken Giles, a spokesperson for the Consumer Product Safety Commission in Washington, D.C., estimates that less than 15 percent of American homes have a carbon monoxide detector somewhere on the premises. Comparing that to the 93 percent of American homes that consistently report smoke detectors in industry surveys, Giles considers the number pathetically low.

"We think and recommend that every home should have an alarm," he says. "We also recommend that every furnace system be checked by a professional before you turn it on for the winter."

Getting that message out in any sort of a consistent manner is no easy task. New York state law mandates carbon monoxide detectors in all one- and two-family houses, condominiums, and co-ops built after January 1, 2002, but in a city like New York City, where the vast majority of buildings predate this cut-off, it falls on tenants to police their own dwellings. Even with printed warnings on heaters and furnaces, however, Touger estimates that a full third of the emergency cases that demand treatment in his unit stem from faulty heating and ventilation systems.

"We certainly are eager to engage any type of public education this time of year, because a lot of the cases we see should have been preventable," Touger says.

The sad irony of carbon monoxide poisoning, however, is that it usually takes grisly incidents such as last month's triple suffocation to send local residents to places like the Forest Ave. Home Depot on Staten Island, where detectors sell for $26 and up. Once there, the dust-covered plastic encasing each detectors offers a quick testimony as to why many still call carbon monoxide "the silent killer."

How Carbon Monoxide Kills

The primary challenge in elevating carbon monoxide to the A-list of feared chemicals is the molecule's own insidious nature. A natural byproduct of any combustion process involving carbon-based fuel, carbon monoxide is generally present any time you have a steady flame. Gasoline motors, natural gas furnaces, charcoal grills, and propane space heater all contribute varying amounts of carbon monoxide to the atmosphere. In most cases, however, circulating air keeps the amount of carbon monoxide molecules below the 9 parts per million threshold set by the Environmental Protection Agency as a suitable safety standard.

During the winter, however, windows seal up, aging furnaces and ventilation ducts go back to work, and snow rises to block automobile tailpipes. As the number of escape routes diminish, the amount of carbon monoxide in the air can quickly accumulate, rising to unhealthy, even lethal levels. Early symptoms of carbon monoxide exposure include nausea, dizziness, and splitting headaches. All are signs of the brain expressing its extreme discomfort at the lack of oxygen coming in through the bloodstream, but because they share a similarity to common flu symptons which also hit this time of year, many go overlooked until too late.

"Carbon monoxide is hard to diagnose," says Touger. "You have to have a high index of suspicion, especially this time of year."

Carbon monoxide's insidious nature extends to the molecular level as well. Carbon monoxide and ordinary oxygen molecules share a similar structure. Hemoglobin, the molecule responsible for transporting oxygen in the blood, binds aggressively to carbon monoxide almost as if tricked. As more and more oxygen-carrying hemoglobin molecules become carbon-monoxide carrying hemoglobin molecules, the amount of oxygen that actually reaches the bodies oxygen-dependent tissues starts to plummet. Slowly but surely, the body's own respiratory system is tricked into betraying itself.

"If you give a red blood cell the choice between binding to carbon monoxide and binding to oxygen, it will favor CO over oxygen 200 to 1," says Tyrrell, summing up the grim calculus.

The primary purpose of Jacobi Medical Center's hyperbaric chamber, he says, is to simulate the high pressure of a scuba dive. Just as scuba divers experience altered blood oxygen concentrations chemistry at extreme depths, a patient breathing pure oxygen inside a pressurized chamber will experience a surge in bloodstream oxygen. More oxygen means a higher likelihood that carbon monoxide, when it finally dislodges from hemoglobin, loses its place to an in-rushing oxygen molecule. With nowhere else to go, the carbon monoxide is then flushed out of the patients system through ordinary respiration.

Simply put, hyperbaric treatment can tilt the 200-to-1 ratio back into a poison victim's favor. "It's the quickest way to get rid of CO," Tyrrell says, noting the chemical shorthand for carbon monoxide.

Next to home heating systems and improperly ventilated appliances, the most common culprit in most poisoning cases is the automobile. Dr. Bob Hoffman of the New York City Poison Center says a statistical analysis of carbon monoxide-related calls coming into his center reveals two yearly "spikes."

"The first spike is early winter," Hoffman says. "That's when everybody turns their heaters on for the first time. The first couple of cold days always make us nervous."

The second spike comes after the first major snowfall. Drivers who fail to notice snow-blocked tailpipes often experience the initial symptoms of poisoning and call in seeking help. Such cases often don't require treatment once the victim has removed himself from an enclosed area. In the case of children exposed to carbon monoxide, however, automobile-related calls tend to be the saddest ones received at the poison center.

"A parent will put the child in a running warm car to keep it warm while he or she shovels out the tires," says Hoffman, relaying a scenario that plays out at least once a winter. "In the worst case, the parent mistakes the child's sudden unconsciousness for sleep, giving suffocation a better chance to occur."

Hoffman says his center has the budget and the media channels to get the message out. The only thing missing is the general sense of dread for these messages to tap into. Outside from the occasional tabloid headline, most New Yorkers can spend an entire year blissfully unaware of the menace lurking in their homes and cars. Even a city law mandating detectors in all homes, something Hoffman doesn't see coming anytime soon, would require a fatal accident or two to spur the proper outrage and enforcement.

"Every winter there's a lot of education both through the media and through the health commissioner's office: notices to check your boiler, check your heater, clean out the tail pipe in your car," Hoffman says. "Despite all that work, CO is the number one killer in terms of poisons, both in the city and across the nation."

Hoffman notes the recent suffocation deaths in the Bronx and expresses hope that, with the publicity such sobering events generate, the number of detectors in New York City homes will continue its slow climb.

"If any good ever comes out of anything, if you can save a couple lives because of these three, you've done a good job," he says.

Capital Budget

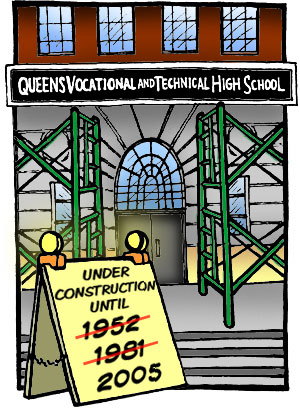

This year, Mayor Michael Bloomberg promised to do what the last eight mayors could not - build a new cafeteria and gymnasium at the Queens Vocational and Technical High School in Long Island City.

This year, Mayor Michael Bloomberg promised to do what the last eight mayors could not - build a new cafeteria and gymnasium at the Queens Vocational and Technical High School in Long Island City.

The school was first promised the new facilities back in 1948. However, decades of delay at the Board of Education, budget cuts, and debate among lawmakers over the mission of vocational schools stalled the project. For years, students have held gym classes outside, even in the winter.

Construction crews finally broke ground this summer and the new building is slated to open in September 2005. Mayor Bloomberg, who says he has cut school construction costs by a third, is now promising to complete other long-neglected school projects across the city.

Earlier this month, the mayor announced the most ambitious school construction plan in the city's history. He said he would spend $13.1 billion over the next five years to build 76 new school buildings for nearly 63,000 students. However, many doubt that the school construction plan will become a reality since half of the money must come from the state government in Albany.

The school construction plan is part of the city's capital budget. The capital budget, which totals about $6 billion a year, funds construction and repairs for the infrastructure of the city - the sewers, bridges, roads, subway lines, and wires and cables that keep the city running.

The capital budget, many experts say, is complicated, prone to cost overruns and delays, and largely ignored by lawmakers, the press and voters. It is also a delicate balancing act: spend too little and the city's infrastructure crumbles; spend too much and the city plunges further into debt.

"It is a real dilemma," said Preston Niblack of the Independent Budget Office. "The key is to find a sustainable level of spending. And we really haven't been able to do that."

WHAT IS THE CAPITAL BUDGET?

The city's capital budget is separate from the annual $44 billion operating budget, which covers daily expenses. The annual capital budget is approximately $6 billion; the city contributes $5 billion of it and the rest comes from state and federal aid.

By definition, a capital project involves the purchase, repair or construction of physical items that cost over $35,000 and must last for at least five years. Most of the city's capital budget goes to three areas: 33 percent goes to sewage and water systems, 20 percent goes to schools, and 20 percent goes to transportation. (See graphic for how capital money is spent.)

Where The Money Goes: NYC $49 Billion Capital Budget For the Next Ten Years

|

Every other year, the city issues a ten-year strategy that outlines the needs and goals for construction and repair over the next decade. Each year, the mayor presents an annual capital budget that proposes what should be built in the coming fiscal year and the three following years. A more detailed report of what is currently being built or repaired, called the capital commitment plan, is issued three times a year. (See Capital Budget Components sidebar below.)

Unlike the operating budget, which is funded largely by taxpayer money, most of the money for the capital budget comes from debt, usually through the sale of bonds. This debt must be repaid over decades to come.

"The rationale for using debt to pay for capital projects is that future generations will use and benefit from them, and so they should pay part of the bill," said Douglas Offerman of the Citizens Budget Commission.

Each year, the borough presidents are given a small portion of the capital budget to spend in their borough. The amount is based on population and the size of each borough. For example, Manhattan receives about $11 million and Queens receives about $28 million a year.

MISSING THE BIG PICTURE?

The capital budget goes through a long approval process and community boards, city agencies, the City Council, the borough presidents and the mayor all have input.

Still, the capital budget is often overlooked for a number of reasons. First, it deals with infrastructure, things like streets, sewers, and tunnels that most New Yorkers take for granted and notice only when they break.

Some argue that the capital budget process is further complicated and obscured by government bureaucracy. The 59 community boards meet each fall to determine neighborhood priorities, but critics argue that they often just pick from a list of projects presented to them by the city. The City Council used to hold separate hearings on the operating budget and the capital budget, but now the two fiscal plans are covered in one hearing. Long-term needs are often overshadowed by immediate budget issues.

"It should be a dynamic, planning oriented process," said Richard Anderson of the New York Building Congress. "But it comes across now as a paper process, with various city officials going through the motions."

In addition, the capital budget does not receive the same press attention given to the annual expense budget battles when every lawmaker and interest group in the city fights for their piece of the pie. Last June, the day after the capital budget was approved, it earned just a few sentences in New York City's five daily newspapers.

Finally, the capital budget deals with the long-term projects that can take decades to complete and can often run over budget or be delayed. Only a third of the money authorized each year is actually spent during that time frame. The rest is carried over into the next year and the completion date for projects are postponed.

"Capital budgets are unpredictable," said Joe Weisbord of Housing First, who urges funding for housing construction. "One way to manage the budget is to slow down a project or roll the money from one year to the next. But these decisions have serious consequences for the long-term needs of the city."

BRINGING HOME THE BACON

One of the few times New Yorkers actually hear about the capital budget is when politicians hold "ground breakings" or "ribbon-cuttings" on a new project.

Each of the 51 New York City Council members can request money for specific capital budget projects, and they represent some of the few tangible accomplishments a council member can point to come election time.

Last year, Bronx Councilmember Oliver Koppell lobbied for money to design a new library at John F. Kennedy High School, and to improve the libraries of three other schools. Queens Councilmember Joseph Addabbo Jr. requested $500,000 to build a skateboard park in Rockaway. And Brooklyn Councilmember Erik Dilan allocated more than $1 million for a youth center in Bushwick.

|

Two years ago, Brooklyn Councilmember Diana Reyna requested more than $1 million to build a new bathroom in Sternberg Park in Williamsburg. The budget item was approved, but the project was delayed in the city's process of soliciting bids from contractors. Dates for the start of construction were postponed three times, and work still has not begun.

"It is not just a matter of getting the funding approved, but continually monitoring the administration to make sure that the project is moving ahead," said Karl Camillucci, chief-of-staff for Reyna.

During a difficult fiscal crunch, local politicians say they sometimes find their pet projects slashed from the budget. Last year, for example, City Council members said the mayor eliminated capital money for library improvements and used it to plug a hole in the operating budget. The Office of Management and Budget said this is not true and all changes are agreed to by the administration and City Council staff.

STATE OF THE CITY

After the fiscal crisis of the 1970's, the city's infrastructure was in bad shape as many repair projects were delayed and new construction was abandoned.

The East River bridges became a poster child for municipal neglect. Repairs to the Williamsburg Bridge ended up costing about $600 million, some $400 million more than it would have if routine repairs had been made when needed.

During the 1990's, as the city's economy improved, the government spent more money - about $6 billion a year - to get its systems in working shape, or the technical term, in a "state of good repair."

But every improvement or new project is paid for with borrowed money and will cost New Yorkers for decades to come.

Every year, a significant portion of the city's annual expense budget goes to debt payments, the interests and principal on outstanding debt - and this amount grows each year. In 2002, the city paid $3.8 billion in debt payments. The Independent Budget Office estimates it will rise to $5.5 billion or nearly 20 percent of all tax revenue in the city by 2008.

Eventually, debt payments cut into services like senior citizen centers, library hours, and the number of teachers in the classrooms.

"Every dollar spent on debt service is a dollar that you don't spend on the day-to-day expenses of the city," said Douglas Offerman of the Citizens Budget Commission.

Today, facing another fiscal crunch and rising debt payments, the city is once again looking to cut costs.

But just keeping the city running is a monumental challenge. New York's infrastructure is old, it takes a beating from its 8 million residents, and it is still in need of billions of dollars in repairs. More than 40 precent of the capital money spent over the next ten years - some $17 billion - will go just to keeping the city's bridges, schools, streets, parks, and sewers in working shape.

CRITICAL ISSUES IN THE CAPITAL BUDGET

Education

Courts/Public Safety

Housing

In December of 2002, Mayor Bloomberg presented a plan to build or renovate 65,000 homes over the next five years. It represented the most significant housing proposal, many said, since 1986 when Mayor Ed Koch promised to build some 100,000 new homes.

While many housing advocates praised the mayor for his vision, they warned that the city's capital budget for housing was being slashed. The city's most recent ten-year capital strategy proposes cuts of $1 billion over the previous plan. The mayor hopes to offset the cut with federal funds from the Housing Development Corporation and the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, but this money does not fill the gap.

"We are facing the worst housing crisis in 50 years," said Joe Weisbord of Housing First. "Even with the mayor's plan, we are back to spending less [in the capital budget] than we planned to in 2002."

Parks

Capital funding for parks has remained fairly constant in recent years. However, parks advocates warn that the capital budget is being used to make up for cuts to the annual operating budget. For example, parks workers who do regular maintenance are being laid off, causing equipment to deteriorate more quickly. The city then makes up for this by ordering a capital overhaul, sometimes as soon as five years after the previous one.

"The parks department has to rely on capital money to replace equipment, rather than paying for ongoing maintenance," said Stephanie Elson of New Yorkers for Parks. "This will cost the city more in the long run, especially when you consider the interest being paid on the debt."

Sanitation

Since the closing of the Fresh Kills landfill in Staten Island in 2001, the cost of disposing of the city's 36,000 tons of daily trash has risen.

Over the next four years, the city plans to spend approximately $1.2 billion, a 21 percent increase over the past, to improve the city's marine transfer stations. The stations are located on the city's waterways, where the waste will be loaded onto barges and shipped to train stations that haul trash out of state.

Sewers And Water

Nearly a third of the capital budget goes to pay for sewers and water systems. Over the next four years, the city plans to spend $7.5 billion, more than $2 billion than it did over the same time period in the past. The city is investing billions in pipes and water mains because they crack and break hundreds of times a year. Some of the city's pipes were built 150 years ago.

One of the most costly projects is the massive water tunnel 3, which will bring drinking water from upstate reservoirs into the city. When the tunnel is completed in 2020, it will cost an estimated $6 billion. The tunnel construction began in 1969 and has been halted several times because of a lack of funds.

Debt for construction on sewers and water mains is backed by bonds from the Municipal Water Finance Authority and New Yorkers' monthly water bill.

Transportation, Roads, Bridges

Over the next ten years, the city estimates that it will have to spend $9 billion to maintain roads, bridges, tunnels, and mass-transit. As in the past, most of the money goes to big infrastructure projects like maintaining bridges. In fact, repairs to roads and bridges consume 84 percent of the transportation capital commitments. Street resurfacing will cost an estimated $2.3 billion over the next 10 years, an increase of 13 percent.

Between now and the year 2013, the city will contribute $748 million to the New York City transit capital budget, which pays for new subway cars and track repairs.

However, projects like the Second Avenue subway, the new lower Manhattan transit hub, and the extension of the 7 train into the west side of Manhattan are not included in the city's current plan.

*******

RELATED LINKS

• Capital Commitment Plan 2004

• Adopted Capital Budget 2004

• New York City's Ten Year Plan 2004-2013

• Guide to the Capital Budget from Independent Budget Office (in pdf format)

Lessons For

A year ago Mayor Michael Bloomberg put the finishing touches on a city budget that forced some $6 billion of deficit-reduction actions. That bold fiscal success - based mostly at the last moment on an 18.5 percent increase in property taxes - is in sharp contrast to the mayor's political loss with his three city charter proposals in the election this month. Yet the release of the city comptroller's annual financial report this month is a reminder that the mayor's budget balancing last year has worked remarkably well. At least in broad budget terms, city services in the 2003 fiscal year (ending June 30, 2003) remained stable - in spite of the severe economic and fiscal crises caused by national and city recessions, the World Trade Center attack, and a previous administration's tax cuts.

At the same time, buried in the comptroller's report and the sad little 2003 Charter Revision Commission exercise are some lessons for more democratic fiscal management. A public distaste for mayoral hubris seems to have fired up opposition to the nonpartisan election ballot question. But the defeat of the obscure ballot questions 4 and 5 reined in other dubious mayoral power grabs as well. Question 4 would have expanded mayoral discretion in city contracting, yet the city comptroller's new annual report cites several contracting problems - particularly in information technology procurement -- that suggest more, not less, outside monitoring. And question 5, an odd mayoral wish list of expanded powers, included the elimination of the preliminary mayor's management report (discussed in October's Finance column). Yet the comptroller report suggests current management can't even count potholes accurately.

Budget Stability and Services

The comptroller's report reflects the depth and vision in last November's budget modification. The property tax increase meant a full-year, recurring $1.7 billion revenue boost, helping the city to end the 2003 fiscal year with more than a $1.4 billion surplus. The carry-over of that surplus to the current year served as a big stabilizing factor. Political acceptance of the property tax increase -- and the new personal income and sales tax rates added in June 2003 for the current fiscal year's budget -- may or may not be evident in the recent council elections, but none of the re-elected incumbents seems to have suffered for their votes for new taxes.

The payoff for the revenue initiatives is clear in the comptroller's report. In several large service areas, budgets were stable or up substantially in 2003. If the budget numbers for fiscal year 2001 (i.e., the full fiscal year before September 11) are compared with those in fiscal 2003 (the first full fiscal year after September 11), the results range from an 18 percent increase in public education spending to just over a one percent increase in public safety and judicial spending:

· 2003 education spending was up 18.4 percent to $14.5 billion.

· Health spending rose to $2.7 billion from $2.3 billion, up 16.3 percent.

· Social services spending went to $9.8 billion from $9.2 billion, up 6.8 percent.

· Public safety expenditures hit $8.8 billion, up 1.2 percent from $8.7 billion.

Money, of course, does not guarantee services. But the few available numbers suggest stability and even some gains. The increase in education dollars is apparently largely the result of delayed salary increases. The number of full-time pedagogical staff, for example, was stable over the two years, although the ratio of students to pedagogues was up fractionally (11.2 to 11.6). As for educational performance results, indicators are few: the percentage of pupils meeting and exceeding standards in English language arts rose over two years nearly one percentage point in grade 3 (to 43 percent) but lost 1.2 percentage points in grade 8 (to 32.5 percent!).

In health, there are even fewer numbers in the comptroller's report. At the city's municipal hospitals, the number of billable outpatient day and emergency room visits was down slightly (from 5.7 million to 5.65 million, or just under one percent) from 2001 to 2003 - arguably a small improvement. There are also few statistics in social services. The number of persons receiving public assistance dropped from 497,100 in 2001 to 421,500 in 2003 (over 15 percent). Since 1994 the number of recipients is down 719,100, or 63 percent. (Neither the semi-annual mayor's management reports nor the comptroller's report can say where the former recipients are today.)

In the public safety area, the comptroller's statistics on service delivery point out that from 2001 to 2003 the number of uniformed officers decreased from 38,630 to 36,120 (- 6.5 percent). Nevertheless, the mayor's management report for 2003 (in pdf format) shows that major felony crimes fell by more than 14 percent during the same two years - an interesting opportunity for productivity analysis in a $3.5 billion agency.

Another section of the comptroller's report that is useful for measuring budget effects is the one on contracting. It shows that between 2002 and 2003, service contract expenditures (on everything from computer and child welfare services to legal and youth services) rose almost seven percent, from $6.66 billion to $7.02 billion. Most of the categories of health, social, and human services included here show little change. But there are some big-dollar exceptions to the status quo:

· Contracted homeless-family services were up 35 percent, to $297 million.

· Contracted individual homeless services went up 9 percent, to $148 million.

· Contracted employment services were up nearly 14 percent to $339 million.

· Contracted day care services were down 14 percent, to $331 million.

Contracting

The votes against ballot questions 4 and 5 were slightly less harsh than the vote against nonpartisan elections (64 percent and 66 percent against, respectively, vs. 70 percent). But they were also questions obviously of much less interest, with about 100,000 fewer people voting on 4 and 5 than the 471,000 who voted on question 3. The low turnout for the ballot questions (less than 13 percent of registered voters, according to The New York Times post-election figures) and the 100,000 non-responses on questions 4 and 5 among even those dedicated folks should be a signal that constitutional change is too important to trust to mayoral-driven summer exercises.

Coincidentally, the release of the comptroller's annual report provides some evidence that the few hardy souls who voted down expanding the mayor's contracting powers (#4) and eliminating the mayor's preliminary management report (#5) did the smart thing. For instance, the comptroller found that a $28 million amendment to an $84 million IBM contract "was beyond the scope of the original contract and accordingly required a new procurement. This contract is symptomatic of a greater procurement problem in which large computer contracts are written with vague scopes of work, loosely supervised, and not graded for performance. The Comptroller's Office is closely monitoring such contracts."

As baseball- and football-fan mayors look to new city subsidies for sports teams, it's always useful to keep in mind comptroller audits of these teams. Most recently, the comptroller found the New York Mets owed the city $4.6 million in rent because they "understated revenue by $18.8 million and overstated deductions by $35.4 million." The newest team in town, the Staten Island Yankees, is already following the big-league practices: The minor league Yankees owed the city Economic Development Corporation "$373,517 for various items including electricity, fees or signage revenue, and late payment charges." The audit also found "internal control weaknesses."

An audit of one of the Human Resource Administration computer systems -- its Auto Time System -- "found that the system was incomplete and cost $24.8 million, $15.2 million more than the initial contract amount." Nor did the audit see any way that $15.7 million in anticipated savings would be realized.

The Mayor's Management Report

The vote against ballot question 5 means, among other things, that the preliminary mayor's management report lives. This is a slightly awkward situation, since the mayor made it clear he thinks the document is not worth the trouble. What might invigorate the use (and value) of the February report is closer cooperation between the mayor and the City Council, the report's charter-mandated recipient. As noted in our October Finance column, the Council under Speaker Peter Vallone was an aggressive participant in the management-report process. The council held separate hearings and issued in-depth analyses, complete with extensive recommendations for the next round. Over the past two years, both these council efforts have been abandoned.

If the mayor and the council need any evidence to get back to serious work on the reports -- the best test of mayoral accountability -- the city comptroller's report is again a useful guide. A section summarizing some " Service Delivery/Program Performance" audits notes, for instance, that "an audit of [Administration for Children's Services] disclosed that the agency does not adequately monitor its 493 contracted day care centers."

Then there are the potholes. Potholes have often been the most visible (and most embarrassing) measurement of a mayor's management skills. The mayor's management reports keep records of potholes and repair operations, but look at what the comptroller found:

"Audit of [Department of Transportation] found that the agency lacks a useful standard for measuring the performance of its pothole repair operations. [The agency] took an average of 57 days - ranging from one to 2,494 days (seven years) to complete 1,774 sampled pothole repair ordersâ€|and some repairs are counted more than once in theâ€| pothole productivity figures."

Whether it's potholes, failed computer systems, the whereabouts of 719,000 former welfare recipients, or education performance standards, there is need for information, analyses, and self-examination in city government. We have budget stability for the moment, but particularly with no strong economic turnaround in sight, the city would gain from a higher standard of accountability in its work and its reports. The ballot voters had it right.

Glenn Pasanen, former associate director of City Project, teaches political science at Lehman College of the City University.

Shrinking Accountability: Proposed Changes To The Mayor's Management Report

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has taken a second step in his quiet plan to diminish the role of the city charter-mandated mayor's management report, the city's key tool for judging mayoral performance. The September management report for fiscal year 2003 (in pdf format) reflects the first step, the slimmed-down text he introduced a year ago. The second step is the mayor's charter revision commission's August proposal to eliminate one of the two annual management reports. This proposal (in pdf format) is buried among several unrelated changes in ballot question #5 for the November 4 election.

The commission's proposal is disingenuous and anti-democratic. It misreads the intent of the charter mandate, shrinking its accountability mechanisms rather than enhancing them. The key question, which the mayor and commission sidestep, is what the two annual reports are supposed to do. The City Council argued for years that Mayor Rudy Giuliani ignored the fundamental role of the management reports. Now Mayor Bloomberg repeats that error. Together, the two annual reports are supposed to link budgets to service delivery. Accountability stems from knowing what each dollar in the budget buys. Without the budget-service links, we are left with widget-counting.

In proposing the elimination of the February report, the charter revision commission argues, for example, that it is outdated, ineffective, and too expensive. Because the commission does not offer any new ideas on how performance will be measured in the single annual report, it is simply arguing that less is more. Furthermore, the current, streamlined September mayor's management report is not a good model. It has some virtues - neighborhood statistics, five-year trends in data, internet accessibility, concise agency mission statements, for example - but it is weak in such basic management-reporting areas as budget targets, timely data, and productivity measurements.

THE 2003 MAYOR'S MANAGEMENT REPORT

The September report is a useful guide to city policies and services, particularly at the neighborhood level. There are local maps, indicator definitions, data-saving and manipulation devices, and a lot of information. This permits much "customizing" of the data and should be a valuable asset for managers, community service advocates, and researchers.

But the report's weaknesses outweigh its new accessibility. One major limitation is the lack of any mayoral overview. There is no introduction, no summary, and no prospective vision. Rather, there are over 200 "critical objectives" in city agencies (the first: "Reduce smoking and the illness and death caused by tobacco use,"and the last: "Encourage the contribution and use of donated materials.") These broad, bland objectives are followed by similarly brief "performance highlights," and then occasionally useful "performance reports."

True, there are some clues to the mayor's priorities. The Human Resources Administration, a $6 billion agency, is clearly not a priority, with only three broad critical objectives ("Provide public assistance, food stamps or medicaid benefits to eligible individuals and families|.") and only three and a half pages of performance reports on those objectives.

The Department of Education, a $12.5 billion agency now under the direct control of the mayor, gets a little more attention - 12 critical objectives ("Increase attendance" is the first; the last is "Work with the School Construction Authority to design, construct, modernize and repair durable, functional and attractive education facilities, on schedule and within budget.") followed by seven and a half pages of performance reports. Unfortunately, 24 of the 46 major performance indicators (52 percent) have no 2003 information, so that the most recent data on such matters as graduation and drop-out rates are 15 months old.

One of the most obvious agencies for judging mayoral performance is the Department of Sanitation, where the closing of the Fresh Kills landfill has resulted in huge new costs. But the three pages of performance reports are uninformative, with new detail provided about snowfall and salt used last winter, but little about current and prospective costs of trucking 12,600 tons of waste out of the city daily. Several cost-per-ton indicators have no 2003 data nor any targets for fiscal year 2004. (The agency says changes in policy during the year have delayed estimates.) The nearly 40 percent increase in sanitation costs (now $1 billion a year) in just four years would seem to call for a fuller analysis.

The September report also falls victim to the widget-counting data that Rudy Giuliani loved. The number of pages actually increased by 36 percent over last September's report, largely due to the inclusion in each agency of the number of calls into the agency on the new 311 phone line. We now know, for instance, that there were 7,228 calls to the Department of Transportation about "dangerous" ("priority") potholes and 6,360 calls about (not dangerous? non-priority?) other potholes reported during a 4-month period ending June 30. What's the point? But there is minimal current and prospective cost data about road repair costs, and one big success in 2003 - 89 percent of potholes filled within 30 days - prompts a planning target for 2004 of only 65 percent.

BALLOT QUESTION #5: VOTE NO

The 2003 charter revision commission has posed three ballot questions for the November 4 election. Question #3 is the widely discussed nonpartisan election issue. Question #4 makes adjustments to the city's contracting process. Number 5 is entitled "Government Administration," and includes four unrelated changes:

· expand mayoral authority over the city's administrative law practices

· permit the Conflicts of Interest Board to increase penalties

· change the structure of the Voter Assistance Commission

· "require annual publication only of the Mayor's Management Report. The Preliminary Mayor's Management Report would no longer be required."

Since the current charter mandate on the management reports is about mayoral accountability, it is disingenuous to call the change "administrative." This is a proposed change about the reporting responsibilities of the city's highest elected official and the public's access and use of that information. It is an important question that deserves more than the brief attention it received in the mayoral-dominated charter revision commission.

The Commission in its final report gives three reasons for the elimination:

· "it is no longer necessary as a result of technological advances which allow for greater public accountability.

· it is not an effective means of assessing or improving agency performance; and

· it is relatively expensive to produce without a lot of 'bang for the buck' in terms of reporting on the delivery of citywide programs and services."

This is a rather lame rationale, a mix of throwing the baby out with the bathwater and saying the mayor can't produce a cost-effective report, a curious admission of managerial defeat.

The speaker of the City Council, Gifford Miller, strongly opposes the elimination of the February report. (The council will hold a hearing at City Hall on Question 5 on October 16, 2003, at 10 am.) The council position is important because the management reports are directed to the council, and the council is currently mandated to hold agency hearings on those reports and issue its own findings. During the Giuliani years the council aggressively used the mayor's management report hearings to question agency spending and make the case for enhanced performance indicators. One of its reports (In PDF format) from March 2001 illustrates the importance of the February preliminary mayor's management report:

"The Charter clearly intends the [preliminary mayor's management report] to relate performance measures to proposed budget appropriations so that the council, its mandated recipient, can consider what agencies have accomplished or produced with the resources allocated, and the effect of budget proposals, during the budget process.The [preliminary mayor's management report] otherwise falls far short of achieving its intended purpose|.

"Absent a precise delineation of the link between specific appropriations (past or proposed) and programmatic performances, the [mayor's management report] fails to provide the legislative body with the information it needs in order to assess the results of prior funding decisions and determine appropriate funding levels for the future." The elimination of the February management report also eliminates the charter mandate of council hearings and reports. The council would, according to the commission, retain its council oversight powers (Sections 28 and 29 of the charter) and, therefore, by implication, could choose to continue such hearings and reports. But that, of course, substitutes political discretion for constitutional mandate.

In a city whose constitution already gives its mayor extraordinary power, particularly on budget matters, any enhancement of those powers is worth examining closely, particularly when so clearly prompted and packaged by the mayor himself. The City Council and public in general are too often out of the budget loop, and they need all the information, analysis and power the city charter can give them.

Glenn Pasanen, former associate director of City Project, teaches political science at Lehman College of the City University.

To Keep People In New York City, Cut Costs

|

Leaving New York While some New Yorkers are leaving the city, citing bad schools, high housing costs or the daily stresses of urban life, analysts debate whether the exodus is anything alarming or unusual, and what to do about it. Why New Yorkers Are Leaving: The City Is Too Expensive by E.J. McMahon City Schools and Housing Are Inadequate by David Kallick New Yorkers Who Left: Rondrae Hunter A Frustrating Apartment Search Allison Woods Struggling with Strollers and Schools David Bassine Fear of Terrorism Stefan Kochi Bad for Business |

If you want to keep people in New York, the first thing you have to do is to reduce the staggeringly high cost of staying here. The single biggest factor driving that cost is a crushing state and local tax burden.

We have become so used to hearing about New York City’s high taxes that we have become sort of numb to it. But consider these statistical tidbits:

• New York’s overall tax burden is by far the highest found in any of America’s largest cities.

• Despite relatively low residential property taxes, the overall tax burden on New York City homeowners is the highest in the state.

• For households with incomes of $100,000 a year (middle class by New York standards) the combined state and local tax burden is 32 percent higher than the average for major cities.

• The commercial property tax is absolutely out of sight, reaching nearly $10 per square foot for prime space in midtown Manhattan. The only city that comes close is Chicago. In most other major cities, it is less than $5. In New Jersey, it is $3.

• The combined state and city personal income tax rate this year will reach a maximum of over 12 percent – highest in the nation, almost double the rate in New Jersey, and more than double the rate in Connecticut or Pennsylvania.

With the exception of the last item in the list, these comparative measures do not reflect the impact of the roughly $2.8 billion in city tax increases that have been enacted since Mayor Michael Bloomberg took office last year, or the $3 billion in state tax increases enacted by Albany this year.

Just because many New Yorkers do not directly pay these taxes, either because they are renters or because their incomes are below the median, does not mean they are unaffected by them. The impact of taxes is pervasive, rippling through every sector of the economy. High taxes ultimately drive down the number of new jobs created in the city and drive up the price of goods and services produced there.

Tackling this problem will require a constant, unrelenting effort to steadily bring down the cost of government at both the state and city levels. This is why it is so important for Mayor Bloomberg to continue pressing municipal labor unions for productivity concessions.

Beyond taxes, the most important factor driving cost is the price of housing in the city. This is a classic supply and demand problem, growing directly out of rent regulation and restrictive zoning and building codes. The answer is to stop treating housing as a socialized good, a government-funded entitlement. Clear away the dense thicket of regulatory barriers to building in New York, and let the market do the rest.

Beyond taxes and housing, improving city schools and doing even more to drive down the crime rate obviously are both crucially important to retaining residents. But if its economy is drowning in high costs, the city will lack the tax base to do those good things in any event.

E. J. McMahon is a senior fellow for Tax and Budgetary Studies, at the Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute.

Bad for Business

Stefan Kochi has lived in Boston since 2001. Leaving New York While some New Yorkers are leaving the city, citing bad schools, high housing costs or the daily stresses of urban life, analysts debate whether the exodus is anything alarming or unusual, and what to do about it. Why New Yorkers Are Leaving: The City Is Too Expensive by E.J. McMahon City Schools and Housing Are Inadequate by David Kallick New Yorkers Who Left: Rondrae Hunter A Frustrating Apartment Search Allison Woods Struggling With Strollers and Schools David Bassine Fear of Terrorism |

I moved from Albania to Boston in the early 1990s when the economy was just picking up. I had always wanted to move to New York, but there are dreams and then there is reality, so I stayed in Boston where the high-tech industry is very developed.

In 1998, a couple of partners and I created a business building Internet sites for start-up companies. When we decided to open an office in New York City, I moved there and rented an apartment on the Upper East Side.

From the very first time I went to New York I loved it. I saw the tall buildings and the big organizations behind them: JP Morgan, Time, you name it. I thought, "How do they do it, how do they go from an idea to a business that has lasted so long?" And the energy. New York City has the most energy of any city in the world, at least the ones I've seen. So when I moved to New York, I wanted to stay there for good.

My business was very successful, but then the market started to turn. The start-up market was getting dry, and large companies weren't buying, let alone buying from start-ups with uncertain futures. We had to close the New York office in summer of 2001. The Boston office lasted until 2002, when we shut that down as well.

My inclination was to sell my house in Boston and move to New York. But then I began talking to friends in New York. Everybody was lukewarm about the prospects for the economy. I thought if these people, who I had planned to rely on to start my life in the city and build another business, were not comfortable, the recession must be pretty bad.

So, I returned to Boston. I had a house there, I knew more people. Several were offering me jobs.

Now, back in Boston, I have started a new company with a couple of partners. It is doing well, but considering my experience, I am very cautious about declaring success or defeat. I have been to New York several times on business, and if the opportunity came, I would move to New York in a heartbeat. But I got married last month, so now there is one more factor -- my wife -- to consider. She doesn't think she would like New York, but that's what lots of people who haven't experienced the city think.

Stefan Kochi, moved to New York in 1999 and moved out in 2001.

Private Money for Public Needs

|

Smith's campaign raised more than $200,000, which went to provide parks, jobs for young people and to train the new parent coordinators for the Department of Education.

With the city budget tight but demand for services high, the Bloomberg administration hopes individuals, organizations and corporations will, like Smith and her readers, write checks to New York City. Leading the donors -– and urging others to follow his example -- is Mayor Michael Bloomberg. The billionaire "anonymously" gave $10 million to city cultural institutions suffering the effects of budget cuts and $5 million to help restore Gracie Mansion, the official mayoral home where he decided not to live.

But the mayor's efforts go beyond his personal largesse. He has put an unprecedented amount of effort into bringing private funds into city coffers, creating a revamped Mayor's Fund to Advance New York City, exploring corporate sponsorships and naming an official to market the city (see box). Earlier this month, he announced that the city had signed a five-year $166 million dollar deal with Snapple making its juices, ice teas, water and other drinks "official" beverages of New York City.

"Not in my lifetime has there been this level of concentrated expectation that the private sector will help basic city services," Kathryn Wylde, president of the Partnership for New York, a network of business leaders, told the New York Times.

Despite the obvious appeal of having millionaire corporate magnates pick up the tab for services that we all would otherwise have to pay for through higher taxes, some see pitfalls. Private money can come with strings attached and can vanish when the donor moves on to other interests. Further, since corporations and individuals tend to fund projects where they are located, private money may not be evenly distributed throughout the city.

In light of all this, warns Bonnie Brower, executive director of the City Project, a liberal public policy group, the move to private funding is "very, very much a two-edged sword, if not a dagger to our heart."

LOOKING TO THE PRIVATE SECTOR

As big government has fallen increasingly out of favor since the 1970s, politicians, policy experts and officials have sought alternative ways to deliver services. Many have turned previously public enterprises over to private corporations or non-profit organizations. So, for example, many homeless shelters in the city are run by private organizations, and the city contracts with private agencies to care for foster children. Former Schools Chancellor Harold Levy sought -- unsuccessfully - to have a private for-profit company take over some of the city's most troubled public schools, and former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani failed in his efforts to transfer some public hospitals and the Off Track Betting to private hands.

While Giuliani pursued such efforts, known as "privatization," Bloomberg has focused on the reverse: He wants private individuals and businesses to give money to public enterprises.

This is not a new phenomenon. One only has to look at name plaques on many facilities in city parks and at the City University to recognize that private philanthropy has long played a role in shaping public New York. The city sponsors Business Improvement Districts, in which money from businesses supplement city services such as cleaning streets. And libraries and parks actively seek contributions.

"New Yorkers have a great sense of philanthropy," says Rowena Daly of New Yorkers for Parks. In fact, many New Yorkers who grumble about paying taxes are then more than willing to pay an equal or greater amount in voluntary contributions to a city parks group or their local school parents association.

But Bloomberg has sought to take this to a new level, reflecting a combination of his own conviction, his personal record of giving, and the city's economic slump.

Encouraging private donation is "a big thing" for the mayor, says Mark Davies, executive director of the city Conflict of Interest Board. "It's something he is very interested in."

|

In line with this, Bloomberg has renamed Public Private Initiatives, a city controlled nonprofit started by former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. It is now the Mayor's Fund to Advance New York. Between January 2002, when Bloomberg took office, and this April, the fund raised $14 million; in the seven years between 1994 and 2001 it had brought in only $11 million, not counting contributions for World Trade Center victims. Liz Smith's money was channeled through the fund.

The most touted city fundraising effort has come in the public schools. Last year, Schools Chancellor Joel Klein named Caroline Kennedy Schlossberg to head the Fund for Public Schools, part of the Department of Education's new Office of Strategic Partnerships. Kennedy is supposed to drum up financial support and other help for the public school system and work to make sure private resources are used wisely. Shortly after her appointment, Klein said that the school system needed to harness the energy of the business and philanthropic communities and to make sure their contributions were put to good use. "Who can better accomplish this than Caroline Kennedy by her willingness to say, 'Yes I am behind this effort, I believe we can get an education for every child in New York, not just for some children'?" Klein said.

Since its highly publicized debut, the office has kept a low profile, but it played a role in organizing the September 24 Dave Matthews Band Concert in Central Park, which is expected to raise at least $2 million for city schools, including $1 million from America Online. And the office developed a partnership with The History Channel, in which, according to the New York Times, the cable channel will donate $1 million in scholarships, materials and staff hours. According to the New York Post, Kennedy has also "helped reel in" commitments totaling $49 million to fund a training academy for school principals.

Last week, Bill Gates announced the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundationwould donate $51.2 million to open 67 new small public high schools in the city. That money, however, will go not directly to the school system but to non-profit groups that will help create the schools.

(See related article on grassroots efforts to raise money for public schools.)

PARKS, LIBRARIES AND SECURITY

City Council has also taken up the private money cause.

In August, the council passed a bill to create an Adopt-A-Park program. Picking up on the success of private groups in raising money for Central Park, Prospect Park and other prominent parks, the measure would allow companies, organizations and individuals to adopt all or part of more modest neighborhood parks and playgrounds. Taking cognizance of a controversial proposal to allow corporations to get naming rights to a facility in exchange for supporting it (see box), the bill notes that "the program is not intended to rename any park property or structure, but to provide another mechanism whereby individuals, community groups, businesses and corporations can help the city preserve its precious land and recreational programs."

Parks advocates say they must resort to private funding because parks have been particularly vulnerable to budget cutters. "Over the past two decades, parks have been repeatedly cut in good times and bad," says Daly of New Yorkers for Parks. And certainly in this climate, she says, "we're not going to get more tax dollars for parks."

Some critics worry that parks in affluent areas will be quickly adopted, while those in poorer neighborhoods will be neglected. City Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, Jr., chair of the parks committee and a sponsor of the bill, says he hopes this can be avoided. "The real focus is to help outer borough parks," says Addabbo, who is from Queens. He hopes city officials will approach corporations and organizations to urge them to help parks in less affluent communities. And, a provision that allows groups to provide labor to help their park -- a kind of "sweat equity program -- could also help parks in these areas. Finally, Addabbo says, if a disproportionate amount of contributions reach parks in rich areas, it could free up city funds for those in poorer places.

Like parks, libraries have proved particularly vulnerable to budget cutters and so have long sought private money. But this year, the libraries have stepped up their efforts, launching an Emergency Campaign for the Library that will try to raise $18 million over the next three years, including $4 million a year for the branch libraries in all five boroughs.

The fund drive will include what the library is calling a "take out, give back" campaign. As part of that, the New York Library will begin offering addressed envelopes at branch libraries for people to mail in contributions.

Even services almost all New Yorkers consider essential seek voluntary contributions. The New York City Police Foundation is soliciting money to improve police department technology.

But apparently there are limits. When the city announced plans to close firehouses last winter, efforts were launched to raise private funds to keep the companies operating. The mayor rejected the idea, and the fund-raising effort was abandoned.

PROS AND CONS

Many proponents of private funding do not claim it is an ideal solution, although some do see benefits in it. Getting funds from the police foundation is "just an easier, quicker way for us to fund things that we need," Police Commissioner Ray Kelly has said.

And others see private funding as a way to build community, to give New Yorkers a stake in the services they use -- whether it is the local park or the neighborhood school.

But generally, fund-raising campaigns for libraries, parks and schools argue that city money simply is not available, begging the question of whether, in a better world, it would be.

"It's a sign of the times," says Addabbo, noting that virtually every state in the country is suffering a budget crunch. When there is a sluggish national economy, he says, "these ideas...come about."

People are already highly taxed -– New Yorkers have seen sales, property and income taxes rise in the past 10 months -- but still want services: clean safe parks, art and music programs in schools, museums that are open and affordable, the latest best seller on the branch library shelf.

By paying for some of these things, private fund-raising, says Brower of the City Project, provides a "mechanism to avoid raising the most fundamental question, which is what does it cost to run the city of New York the way we want and need to have it run."

Brower sees a number of problems with increased reliance on private money. "It raises questions of distributing resources not by need but by salability or sexiness." And, she adds, "These gifts always have strings attached." In funding city services, corporations are buying access, if not outright control.

In an effort to make sure private fund-raising does not produce an ethnical quagmire, the Conflict of Interest Board has written an advisory opinion on solicitation of private funds by the city and by city affiliated not-for-profit organizations such as the Central Park Conservancy. This opinion, says executive director Mark Davies, attempts to strike a balance between not discouraging private contributions, while making sure that public access is not restricted and that public officials are not somehow coerced by the private sector. For example, it says that when officials solicit contributions, they must "make clear that the donor will receive no special access to city officials or preferential treatment as a result of a donation."

Another issue is whether the drive for private money will work. Ken Sherrill, a professor of political science at Hunter College, thinks that in the long run, it will not. "Private contributions are not going to provide adequate levels of these things" such as higher education, he said. "At some point, enough voters will become dissatisfied with the level of public services" to demand change.

And it is not just proponents of bigger government who see problems with private funding. By simply contributing to the current system, Sol Stern wrote in City Journal in 1999, business people and others help perpetuate a failing system. "Businessmen shouldn't be embarrassed to judge the schools by the same standards that make them successful in their own companies," Stern wrote. "If they don't, if they continue to insist that they are not 'in the business of reform,' they will become increasingly irrelevant to the 1.1 million children who presently have no choice but to rely on the public schools as they are."

For now, few in city government seem to be heeding such arguments from either the left or the right. They simply want the money. The New York Post recently reported that city officials had reached an agreement with corporate sponsors to pay the $75,000 bill for illuminating the decorative lights on the East River crossings. The city had flipped the off switch this summer, extinguishing the necklace lights that had twinkled on the city skyline since the 1970s. Getting them turned back on, one official told the Post, was "something City Hall worked very hard to do."

Additional reporting by Anne Sachs.

A Taxi Fare Increase?

What a difference being in the private sector makes, at least for transportation providers in New York City.

Before last November’s election, Governor George Pataki and his appointees on the Board of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) said that no fare increase was under contemplation. As every straphanger knows, the base fare increased by 33 percent, from $1.50 to $2.00, just six months later.

By contrast, taxicab owners, who represent the city’s largest privately operated transportation sector, formally petitioned the Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) for a 23.3 percent fare increase in November 2001. The commission held a hearing at the end of December 2001 but took no further action, even though soon after his inauguration Mayor Michael Bloomberg endorsed a taxi fare increase. The taxi industry resubmitted the petition this summer. To date, however, no hearing has been scheduled nor has Taxi and Limousine Commission announced a timeline for consideration of the industry’s request.

Thus, while the MTA was able to raise fares in a mere six months, the city has taken two years without deciding yea or nay on a taxi fare increase and the clock continues to tick.

Although the transit fare increase was controversial, the MTA’s reasoning was not particularly complex. MTA officials based the fare increase on the need to balance the authority’s budget and avoid major service cuts. There was a simplicity to the authority’s logic – higher costs mean higher fares.

The Taxi and Limousine Commission, on the other hand, is instructed by the City Charter to consider “all facts which in its judgment have a bearing on a proper determination” of whether to grant a fare increase. These range from fare revenues to “the return upon capital actually expended.” Thus, the commission has looked into a range of issues including changes in taxi operating costs, changes in ridership, the availability of drivers and fares in other cities. Unlike the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the Taxi and Limousine Commission lacks a clear focus for deciding whether to adopt or reject a fare increase.

It is particularly ironic that the commission itself was behind much of the increase in taxi operating expenses in recent years. The commission mandated that only new vehicles can be put into service as taxicabs, required the more-expensive stretch version of the Ford Crown Victoria, and insisted on expanded insurance coverage for the vehicles. These actions were long overdue and benefited the riding public. Yet when it comes time to underwrite the costs, the Taxi and Limousine Commission hesitates.

Not so at the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The MTA has also increased service (largely in response to rising ridership) and bought fleets of new rail cars and new buses. The MTA invested billions of dollars in the process, much of it paid for through fare-backed borrowing. No one questioned whether this spending needs to be paid for, either through fares or government subsidies.

One area where the private and public sectors both experience problems is with tracking of expenses and revenues. The MTA came under blistering criticism for hiding the true state of its finances, first painting an overly rosy pre-election picture of its finances and then drawing what auditors viewed as an artificially gloomy picture after the 2002 election.

The finances of taxi owners have often been fairly opaque, the picture complicated by the diversity of operations within the industry. But at least the MTA keeps records, however open to criticism. The Taxi and Limousine Commission, on the other hand, has not conducted its own analysis of taxi expenses or the need for a fare increase in nearly a decade. Until recently, TLC pointed to the city charter’s provision that the burden of proof for showing that current rates are “unreasonable” lies with the taxi industry. That is fair enough and industry figures submitted financial information to justify their fare request. But recently, the city decided to use a consulting firm to conduct an independent analysis of taxi industry finances. That step may be long overdue but it will further stretch out the process.

This sort of contrast between public and private transportation providers is evident not only with the fare issue but also with another big issue affecting both taxicabs and transit: the supply of service. The MTA has a well-developed methodology for assessing whether more buses or trains are needed on each route. MTA staff regularly observe levels of crowding on trains and buses; this information is feed into periodic reviews of service levels. Thus, when fare incentives, service improvements and other forces produced record-fast growth in subway and bus patronage, the MTA expanded service. Not enough, said critics, and not quickly enough, but at least someone was keeping track and taking some action.