(photo: Metropolitan Transportation Authority/Patrick Cashin)

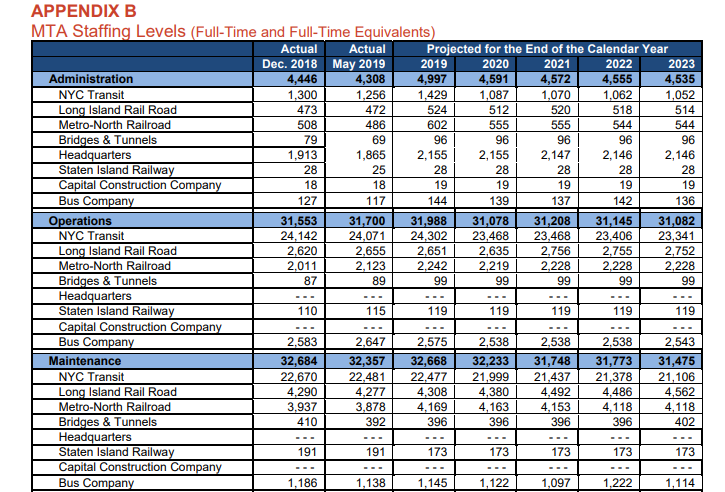

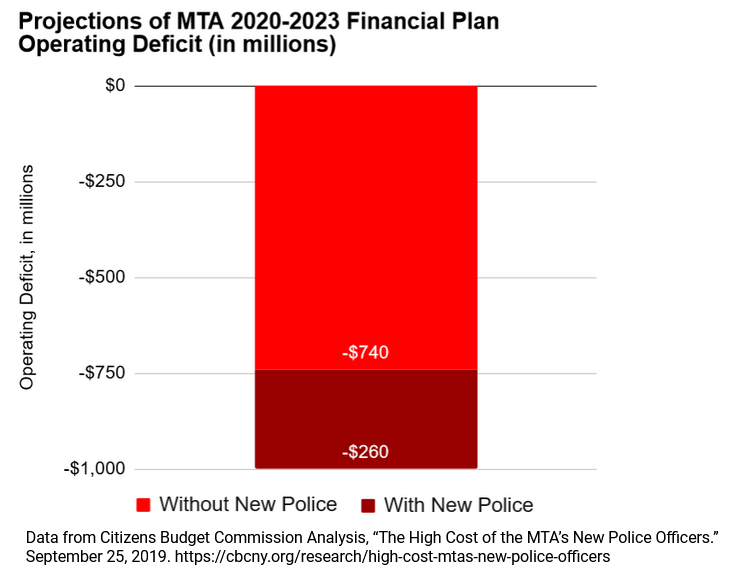

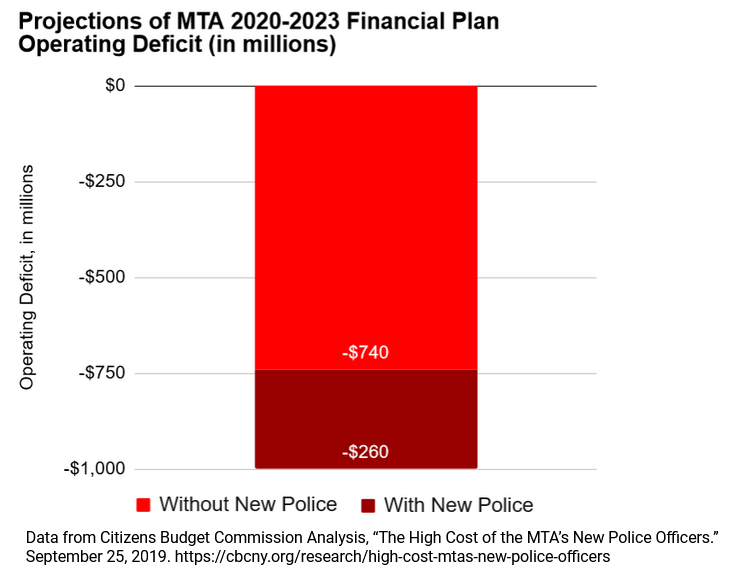

MTA Chair and CEO Pat Foye says the transit authority’s operating budget is in “dire” condition and independent budget watchdogs are alarmed its deficit is growing to unmanageable levels. Citizens Budget Commission estimates the MTA will be $740 million in the red in 2023 -- and this does not include new debt payments for the new, massive $51.5+ billion 2020-2024 capital plan. Separately, NYPD data shows subway crime is down 3% from last year, and Police Commissioner James O’Neill says the subway, which carries 6 million passengers a day, averages only six major crimes a day.

Given the gaping budget hole -- which recently led to cuts in bus service on the B46 -- and the low crime rate, we wonder how the MTA justifies a costly increase in the size of its police force by 581 more officers and supervisors as first uncovered by Gothamist to address “quality of life issues.” This larger MTA force will cost the authority an additional $260 million more in operating costs over the next four years, as calculated by Citizens Budget Commission, and will force cuts elsewhere in the operating budget -- including, logically, in transit service.

The MTA should make a decision of this magnitude based on a transparent, data-driven analysis that shows why expanding the MTA police force is more worthwhile than expanding transit service -- or even preserving existing service. The MTA should explain to the transit riding public what an expanded MTA police force can do that the current 2,500 NYPD officers and approximately 300 redeployed MTA police officers patrolling the subways and buses are not doing.

Disappointingly, the decision to increase the MTA police -- which is widely believed to be at Governor Cuomo’s behest -- has been made in a fact-free zone. The reasoning used has also shifted from fare evasion to homelessness to worker and rider safety, or a combination of all of the above. The public discussions by some MTA Board members has consisted of anecdotes and unfounded assumptions on these issues, and MTA staff have not provided analyses that examine alternatives or even dig deeply into existing MTA data.

(Note to MTA Board: MTA police officers guarding a turnstile only pay for themselves if fare revenue at that station goes up by at least the cost of the officers stationed there. Can we see some actual data that supports the argument that spending $260 million over the next four years on more MTA police will increase fare revenue by that much? What about the four years after that, etc.?)

If one of the governor’s stated goals is to reduce the number of homeless people in the subways, let’s see some evidence that an expensive increase in the size of the MTA police force will or even can do that, or that spending large sums on more police is even the best way to do that. Again, where is the data showing a relationship between the number of police officers and homelessness in the subways?

What we are seeing with the MTA policing issue is the latest example of a once-respected public authority that has been politicized and compelled to spend huge amounts on political grandstanding rather than objective priorities. Just last month, the MTA’s $51.5+ billion capital plan was approved by its Board before it published a needs assessment that establishes detailed baseline costs for getting the system to a state of good repair.

Governor Cuomo has publicly called on the MTA to be more professional and efficient. We agree, but competent, professional management is fact- and data-driven, and does not make decisions based on the politics of the moment. The data here does not support almost doubling the size of the MTA police force from 783 to 1,364 -- especially given the “dire” budget.

Professional, fact-based thinking by the MTA Board and management would mean rejecting this unnecessary expenditure and recognizing there is a direct trade-off between more police and more transit service.

How Much Money Are We Talking Here?

According to Citizens Budget Commission, increasing the size of the MTA police force with 500 new officers and 81 supervisors for the new hires will cost $56.1 million in year one and $119.9 million in year ten. Over the 2020-2023 financial plan, the new officers will cost $260 million and push the MTA’s projected operating budget deficit of $740 million to $1 billion.

Reinvent Albany and other watchdog groups including Citizens Budget Commission, NYPIRG Straphangers Campaign, TransitCenter, and the Tri-State Transportation Campaign sent a letter to the MTA Board calling on the MTA to identify exactly how it will fund nearly doubling the size of the MTA police force without increasing its growing operating deficit. The groups specifically expressed the concern that an expanded MTA police force will reduce the MTA’s ability to maintain a high level of transit service -- its core responsibility.

The MTA still hasn’t said how it will pay for these officers, and what the true cost will be in terms of reductions in staff and service. Its next budget presentation is due at its November 14 Board meeting, and this is likely to be the first time this new expense shows up in its budget. The MTA Board will then approve a final budget at its December meeting, so it is not too late to reverse course.

The MTA’s Many Justifications for Increasing its Police Force

There are many opinions about having more police in the subways and buses. Some oppose over-policing and some are concerned about service cuts, while others believe more police will increase customer and operator safety.

For Reinvent Albany, what cuts across all of these issues is the consistent failure of the MTA -- or Governor Cuomo -- to make credible, fact-based decisions regarding major spending. The governor and the MTA have access to professional analysts, detailed data about operations and crime, and outside experts who could guide their decisions. Instead, this decision has been made without meaningfully using any of them.

We at Reinvent Albany are not criminologists or experts in homelessness or fare evasion. But we do believe in and know the value of data and rational decision-making. Given that the MTA hasn’t been allowed to do its homework, we are providing just some of the data and options that need to be examined before any decisions are made.

Crime

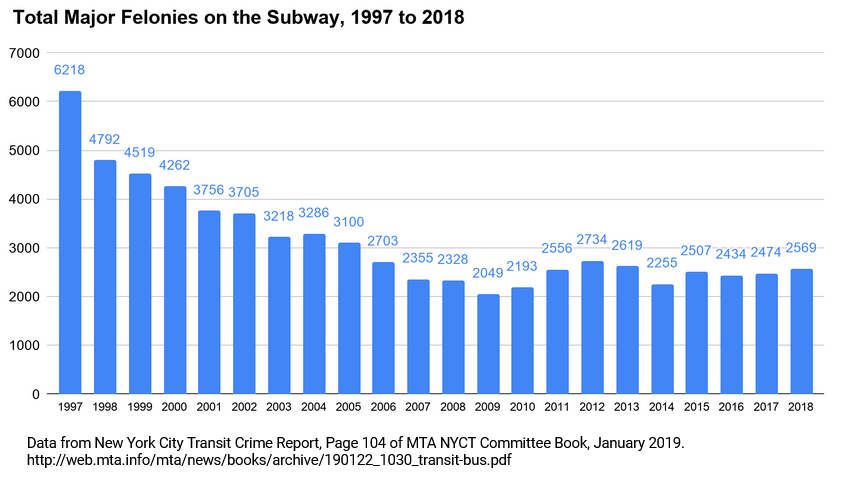

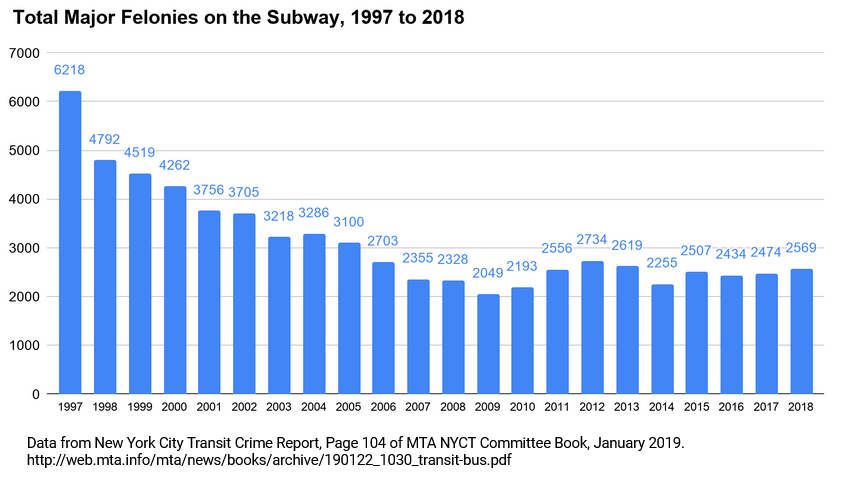

Crime on the subways is a clear area where perception and reality aren’t matching up. Governor Cuomo was recently blasted by the NYPD’s own leader for saying that crime in the subways is on the rise, with Commissioner O’Neill noting that the opposite is true. O’Neill instead said there has been a decrease in crime and “I absolutely disagree with Governor Cuomo’s characterization.” According to the latest stats from New York City Transit, total major felonies are down this year versus last (January-September) -- with 1,774 major felonies in 2019 and 1,799 in 2018.

Major crimes have dropped significantly since 1997, when there were 6,218 major felonies in the subways and buses. For the last four years, major felonies have numbered about 2,500 per year. It is worth noting the decrease happened during a period of increasing ridership: since 1997, annual ridership increased from 1.1 billion to nearly 1.7 billion.

Perception often colors riders’ feelings about crime rather than actual data, as noted in a New York Times piece from earlier this year on subway crime. Social media, for example, is one big driver of perceptions. In speaking with the Times, NYPD Transit Chief Edward Delatorre said that the number of crimes in the subway is so small that “one or two recidivist offenders can enter the system and throw the crime numbers out of whack.” (For scale, there were 95,883 major felonies committed in New York City as a whole in 2018, down from 184,652 in 2000.)

Where particular types of crime have increased yet overall major crimes are flat or decreasing, refocusing existing officers is a more reasonable approach than hiring hundreds of new ones. Two areas that have received considerable attention are hate crimes, which increased from 37 to 65 from 2018 to 2019 (January-September), and assaults against subway workers, which according to the transit workers union (TWU) increased from 61 to 85 when comparing the first eight months of 2018 to 2019.

Homelessness

The MTA recently released a 9-page “report” of recommendations from its Homelessness Task Force. To be clear, this is not a “report,” as there is no credible analysis: it is essentially a directive from the governor to the MTA. The "report," which came after repeated complaints by the Governor about homelessness on the subways, found a 20% increase in homelessness in the subways from 2018 to 2019. The total increase found from a January 2019 survey was from 1,771 to 2,178, an increase of 407 people. This single data point was then used as the sole justification for a directive by the task force to increase the MTA police force by 50%.

Despite the report saying that the task force was “charged with delivering a set of recommendations to the MTA Board of Directors for actions to address the growing number of homeless individuals,” the report says that the MTA will increase its police force.

The MTA Board has not yet approved a budget for these new officers. At the direction of the governor, MTA staff is moving forward with these hires, undermining the fiduciary responsibility of the Board, who must consider how the MTA can best serve riders with its scarce resources.

Fare Evasion

Fare evasion has become a fixation for the governor and some of his appointees to the MTA Board, with more and more demands being placed on MTA staff to address the issue. According to the MTA’s June 2019 data, it lost $240 million to fare evasion over 12 months. But while the MTA has said fare evasion is growing, its Inspector General, who is appointed by the governor, in an audit said the MTA’s fare evasion stats are not credible.

At the same time, the MTA has ramped up enforcement efforts with redeployed police, new signage, and more cameras. If you believe the data, this may not be working. The MTA IG’s audit said that the “impact of these initiatives would be difficult to assess without reliable data on evasion levels and trends.”

The MTA can’t make rational decisions on fare evasion unless it better understands the problem first, and can trust its own data. And before jumping to any solutions, it would be worth assessing any number of other options to get more riders to pay the fare.

Rather than punitive approaches, options include providing better service so riders feel like they are getting what they pay for. The MTA and New York City could enroll more people in the Fair Fares program, which provides low-income riders a 50% fare discount. A Wall Street Journal report found an approach from behavioral psychology of praising paying customers decreased evasion in other systems.

The MTA could also examine further expanding station infrastructure like cameras and more signage to deter the use of emergency gates. (This was the original stated purpose of $40 million in funds coming from the Manhattan District Attorney, which the MTA has erroneously claimed will largely cover the cost of new officers.)

Yet another option is deployment of more cost-effective civilian staff. The MTA has said that more orange-vested staff could provide a deterrent to fare evasion, while providing more customer service. Additionally, the MTA’s Select Bus Service enforces fare payment with its Eagle Teams, who are not police officers. Unlike on other buses and the subway, Select Bus riders do not have to dip their Metrocards on the bus to pay the fare, but instead pay in advance and must show proof of payment upon request of the Eagle Teams. Ironically, the MTA’s Eagle Teams saw 22 staff members cut in the MTA’s 2018 budget reduction program, which in retrospect seems highly questionable as the MTA has said they do indeed pay for themselves.

The MTA Board Must Reject this Proposal

Before spending scarce transit operating dollars that almost doubles the size of the MTA police force, the MTA should work with its own officers and those from the NYPD to establish clear goals and expectations and improve the effectiveness of existing policing. The MTA Board needs to hear fact-based arguments with cost/benefit analyses of the various options to address safety, homelessness, and fare evasion. The MTA Board should reject hiring more police officers until its members and the public have real information about the opportunity costs of this proposal.

***

Rachael Fauss is senior research analyst for Reinvent Albany. On Twitter @RachaelFauss & @ReinventAlbany.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.