Gov. Cuomo announcing Excelsior (Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

In January 2014, Kellyn C. was 49 and had been recently laid off from a human resources position. “You need a college degree to remain competitive,” she said. She enrolled as a first-time freshman at CUNY Medgar Evers College (MEC) in Brooklyn. Three and a half years later, she reports, “I’m doing well. I’m applying myself and forging ahead.” She has 96 credits, a GPA above 3.0, and is on track to graduate in December 2017 or January 2018—all significant accomplishments at MEC, a comprehensive institution offering both associate and bachelor’s degrees.

The Excelsior Scholarship, Governor Andrew Cuomo’s new free college tuition program, was of immediate interest to Kellyn given her upcoming $3,265 tuition bill for Fall 2017 and an income that is just above the thresholds to qualify for federal Pell grants or New York State’s Tuition Assistance Program (TAP). “I’m trying to pursue my degree and there should be something for me,” she said. Yet despite being a highly capable student, Kellyn will not be eligible for Excelsior because of the scholarship’s credit accumulation requirements, which are set at elite levels that she just misses.

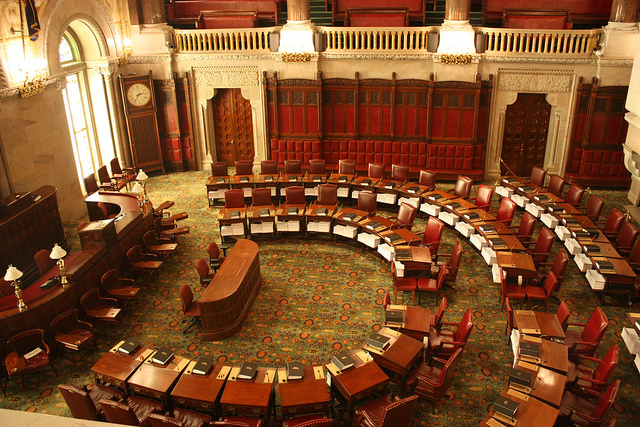

Governor Cuomo announced the Excelsior Scholarship with much fanfare in January 2017 at LaGuardia Community College. Bernie Sanders, standing at his side, touted it as “a revolutionary idea for higher education.” When the bill was signed into law, Cuomo returned to LaGuardia with Hillary Clinton heralding the program as a “beacon of hope” to New Yorkers.

The Scholarship makes CUNY and SUNY tuition-free for students with adjusted gross family incomes of less than $100,000, with the maximum income increasing to $110,000 in 2018 and to $125,000 in 2019. The program is a last-dollar scholarship, which means that the award fills tuition gaps after other federal and state aid have been drawn down. Excelsior offers no additional support to low-income students who already receive enough Pell and TAP aid to cover tuition and fees but often struggle with transportation, rent, and books. Cuomo’s administration has acknowledged as much, describing Excelsior at public events and in television commercials as for “middle-class families.”

Kellyn, while financially eligible for Excelsior with an adjusted gross income of well below the $100,000 threshold, is not academically eligible for the scholarship because she doesn’t meet the requirement of having earned 30 or more credits per year—or 90 or more credits total—by January 2017, the end of her third year in college, even though she’s been picking up credits this summer so that she can graduate in the winter, four years from when she started. “I don’t know where they come up with the 90 credits,” she said, having earned a few credits short of the 90 in her first three years. She is rightfully proud that she’s on track to graduate in four years. If she had been eligible for Excelsior—and she’s still planning to petition for eligibility—getting it “would mean the world to me,” she said.

Of New York State’s 605,000 CUNY and SUNY students, SUNY estimates that only 31,300 students will be eligible for Excelsior, representing 5.2% of all CUNY and SUNY students. The application deadline is Friday, July 21, and if more students apply and are eligible than funds are available in the $87 million earmark, a lottery will be conducted to award the scholarship.

A key reason for the limited projected eligibility estimate is that few CUNY and SUNY students meet the academic criteria of completing 30 credits a year. The percentages of full-time students at three CUNY colleges—Brooklyn College, City College of New York, and York College—who earned 30 or more credits during the 2014-2015 academic year are 31.6% at Brooklyn, 27.4% at CCNY, and 22.8%. at York. The percentages of students meeting the 30 or more credits threshold at CUNY’s community colleges are lower. At Bronx Community College, 11.5% of students met the threshold, and at LaGuardia, 20.2% of students, to cite just two.

At LaGuardia, where Governor Cuomo twice announced the Excelsior Scholarship, only 195 of the 2,480 students who started as full-time students in Fall 2013 graduated within two years and would have met the academic requirements to receive Excelsior during a junior year at another CUNY or SUNY institution. As students get to the sophomore, junior, and senior years and fall off meeting Excelsior’s credit accumulation requirements, Excelsior will become at many campuses an honors scholarship for the academically elite students.

To the extent that there will be students benefitting from Excelsior, they are likely to disproportionately be ones who attend the institutions with the highest four-year graduation rates, like SUNY Binghamton (66.1%) and SUNY Albany (53.0%), rather than ones who attend the institutions with the lowest rates and the rates that arguably most need public policies to support their advancement.

The regulations adopted by New York State’s Higher Education Services Corporation (HESC) in late May outline a number of exceptions to the credit accumulation requirements, allowing interruptions of study “due to circumstances as determined by the corporation, including but not limited to, death of a family member, medical leave, military service, service in the Peace Corps or parental leave.” The “including but not limited to” phrasing allows HESC and colleges to account for unusual circumstances but does not explicitly create exceptions for the primary reasons that students fall behind or take semesters off: academic under-preparation for college-level work; work and life circumstances; and institutional factors, like poor advising, limited course offerings, and subpar faculty.

The regulations further state that students who fall off track and become ineligible for future Excelsior awards will owe one semester of their Excelsior Scholarships back to their colleges. The HESC website reads: “If you fail to complete 30 credits over a 365-day period, the Excelsior Scholarship will cover your first term; however, you will be responsible for the tuition liability for your second term.”

The financial reality of having to pay for a prior completed semester previously thought to have been free and having to pay for future semesters after having gone to college tuition-free may influence initial Excelsior beneficiaries to dropout. Students who miss the credit accumulation cutoffs may start seeing themselves as not made out for college. Falling off the Excelsior cliff is likely to be financially and emotionally devastating to the college success of a significant number of initial Excelsior recipients.

Excelsior’s payback requirement is the most harmful aspect of the program, and it is what is most wrong with the program. The students who self-finance Excelsior repayments and future tuition charges in a valiant effort to earn degrees may find themselves working too many hours to meet their financial obligations to be academically successful.

As Excelsior plays itself out, the scholarship is likely to impact four-year graduation rates positively as students who can stay on track will be more motivated to cross the finish line in four years. Achieving higher four-year graduation rates, however, may be at the cost of decreases rather than increases in the retention of students from freshman to sophomore year, as students who lose Excelsior eligibility drop out. This is not what anyone intended of the revolutionary initiative proclaimed by Senator Sanders. Chano LaBoy, a Senior Trainer and College Access Counselor at the Options program at Goddard Riverside Community Center in New York City, said about Excelsior’s credit accumulation terms, “I’m a little wary as to how it’s going to play out with students who come up short on credits. I’m anxious.”

To address the problems of Excelsior, the Governor and Legislature should eliminate the payback requirement and adjust the credit accumulation requirement to 25 credits per year, acknowledging that a four-year graduation timeline and yearly completion of 30 credits is way too ambitious at many SUNY and CUNY colleges. The requirement that recipients live and work in New York State for the same number of years that they received the scholarship also should be eliminated, as many critics have argued.

In announcing Excelsior, Governor Cuomo got the big idea right. “Today, college is what high school was—it should always be an option even if you can’t afford it,” he proclaimed, and indeed universal college should be the new universal high school, but until the Governor, the State Legislature, and HESC come together to correct the weaknesses of Excelsior, New York State’s free college program is a bait into a trap for students who attend campuses where students hardly ever earn 30 credits a year. Righting Excelsior and making free college freer will require more funding so policy changes may take some time, but for now, New York Excelsior Scholarship is a program for freshmen and academically elite students rather than a revolutionary free college program.

***

Eric Neutuch is a new doctoral student at Northeastern University and an education evaluation consultant.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.