After Silver: Legal Reform is Ethics Reform

The author, Thomas Stebbins

For decades it was an open secret in Albany that the New York Assembly was functionally controlled by the trial lawyers. Sheldon Silver, the former Assembly Speaker, was known to have a lucrative "of counsel" position with the powerhouse trial lawyer firm Weitz & Luxenberg, and most Albany insiders believed that Mr. Silver would not do anything to jeopardize that income. Governor Cuomo himself stated that the trial lawyers were the "single most powerful political force in Albany," no doubt in partial reference to Mr. Silver's position as an employee at a trial lawyer firm.

With the trial and subsequent conviction of Mr. Silver on corruption charges, we now know that the former speaker did virtually no real legal work to earn his "of counsel" income. What he did do was carry the legislative water for the trial lawyers, and we as New Yorkers are left with a state ravaged by lawsuits and litigation.

New York has the highest medical liability payouts in the nation, by a wide margin – even higher than California, which has nearly five times the population. The difference is that California passed meaningful reforms to control medical liability costs, reforms that had no chance in Sheldon Silver's Assembly.

These runaway medical insurance costs are more than a financial issue, they are also an issue of access to healthcare. Hospitals across New York City have been closing at an alarming rate, in large part due to the cost of medical liability insurance. Some hospitals are "going naked" and foregoing insurance entirely, just to keep the doors open. The access to care issue extends upstate as well – at least eight New York counties have no OBGYN services at all.

New York also has the highest construction insurance costs in the nation, due to the odious so-called "Scaffold Law," which Mr. Silver cravenly defended.

The oddly-named law has little to do with scaffolds. What it does is hold contractors and property owners absolutely liable in a lawsuit for workers' injuries even if, in the words of the court, they had "nothing to do with the plaintiff's accident."

New York is the only state to apply absolute liability to contractors. In 2014, Mr. Silver proudly shut down Scaffold Law reforms that would have put our legal system in line with the rest of the country by creating a standard where negligence is proportionate to fault. Silver stymied this common sense reform despite findings that the law cost the state government $785 million a year and corresponds with an increase in injuries. In the wake of his corruption conviction, New Yorkers are right to wonder if Mr. Silver blocked Scaffold Law reform on behalf of his trial lawyer employers.

At the center of U.S. Attorney Preet Bahara's case against Mr. Silver was a referral scheme regarding asbestos plaintiffs. It is no surprise that, given Mr. Silver's control over state government and profit from asbestos lawsuits, New York's asbestos courts were recently rated the worst in the nation, routinely paying out three times the national average. In the aftermath of Silver's arrest it was reported that Mr. Silver's employers, Weitz & Luxenberg, received priority access to juries for asbestos cases. In a particularly brazen conflict of interest, Mr. Silver appointed Arthur Luxenberg, a partner at the firm, to the judicial screening committee, while claiming there was no conflict of interest at all.

We can fix this.

Albany can undo the years of corruption under Sheldon Silver by passing meaningful legal reforms. First, we can enact reasonable controls on medical liability payouts, as California has done, and impose higher standards for the expert witnesses in medical cases. Podiatrists should not be allowed to testify in neurosurgery cases.

Second, we should reform the outdated Scaffold Law to the common sense and widely used standard of comparative negligence. No law symbolizes the corruption of the Sheldon Silver era more than a law that holds contractors and property owners absolutely liable under nearly any circumstance. In doing so we could save hundreds of millions of dollars a year and reinvest that money in schools, roads, and bridges.

Lastly, we need to open up the asbestos trusts to transparency. Currently, plaintiffs are able to sue asbestos trusts, potentially recover millions, and then turn around and sue solvent companies for the same injuries. Because the trusts are not open to transparency, plaintiffs can allege entirely different sets of facts with little fear of discovery. In a recent case against the New York company Garlock Sealing Technologies, the judge forced discovery on the asbestos trusts cases and found fraud in 13 of the 13 cases the court reviewed. Opening the trusts to transparency would go a long way to ensure the funds are reserved for those who are legitimately injured as intended.

It is a new day in Albany. With these changes and more the New York legislature can show us that they work for New Yorkers, not the trial lawyers.

***

Thomas B. Stebbins is Executive Director of the Lawsuit Reform Alliance of New York

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

@GothamGazette

Let's Be Prepared for America's Biggest Corporate Takeover

Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush, via White House archives

Imagine taking over an enterprise with 4 million employees and an annual budget of more than $3 trillion dollars. What if on your first day as CEO, you had to operate without more than 1,000 of your top leaders, faced global emergencies requiring immediate attention and had an agenda dependent on multiple, time-consuming votes by your board of directors?

That's exactly what will happen when the next president takes office on January 20, 2017. And it is why we must prepare better for this presidential transition than we have for any prior.

The new president will inevitably need to deal with an unexpected international crisis, pressing economic issues and many controversies, while simultaneously having to make some 4,000 political appointments, including nominees for about 1,000 key management and policy positions that require Senate confirmation. The new chief executive will have to build relationships with world leaders, take immediate control of the national security and financial sectors, pursue a brand new agenda that requires congressional approval and manage a huge, complex enterprise.

There is an expectation that the nation's newly elected chief executive will hit the ground running, but the transition of power and knowledge from one president to another is often rushed, inefficient, overwhelming, and fraught with risk. Being ready to govern requires hard work and many months of preparation that must start well before Election Day. Candidates must simultaneously campaign to win and prepare to govern if they expect to be effective.

The 2008-09 Bush to Obama transition was one of the best in modern history – with both sides understanding that national security and economic conditions required them to work together in unprecedented ways. But it was only as successful as it was because of the vision and goodwill of the leaders involved; we need a system that is not at the mercy of good intentions, but one that enhances rather than diminishes the capacity of our government to function at a high level.

On December 9, the Manhattan Chamber of Commerce will team up with the nonprofit, nonpartisan Partnership for Public Service to host an event about why the presidential transition matters to the business community, and how this often incomplete and chaotic process can be fixed so that the next chief executive will be ready to govern on day one.

The Partnership for Public Service has created a Ready to Govern initiative designed to get the presidential campaigns to seriously think about standing up transition operations as early as the spring of 2016. This will require designating staff and resources to map out personnel and policy strategies, getting up to speed on the work of more than 100 agencies, developing a management agenda and coordinating with the Obama administration for the transfer of power and responsibility.

As citizens, business leaders want a competent and high-performing government. There can be disagreements about the size and role of government, but there should be absolute agreement that whatever government does, it should do well.

From the business side of the equation, executives need federal agencies to be responsive, and they want some certainty, not ambiguity, about economic policies as well as federal programs and regulations so that they can plan and make the hard decisions that will affect their bottom lines and employees.

If a new administration is unprepared or cannot get its top political appointees in place quickly, it is inevitable that critical decisions on matters small and large will be put on hold, problems will fester and businesses will lose both time and money. All too often, a new president has been in office for a year or more before a full leadership team is in place – and that dearth of leadership has contributed to government dysfunction and ineffectiveness.

If a new administration fails to pay close attention during the transition to choosing capable leaders and planning for effective management - two issues the business community knows a great deal about - policy implementation will suffer and that will affect us all.

The presidential transition cannot be left to chance. Too much is at stake. The candidates must engage in extensive planning, Congress must devote resources and confirm appointees quickly, and the private sector should contribute its expertise when possible and hold those seeking the presidency accountable for preparing to govern.

We may not agree on who should be president, but we surely can agree that better processes and mechanisms must be put in place to ensure that our new government gets set up as quickly and effectively as possible.

***

Ken Biberaj is the chairman of the Manhattan Chamber of Commerce and David Eagles is director of Presidential Transitions for the nonprofit, nonpartisan Partnership for Public Service.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ethical Treatment of Our Homeless Neighbors

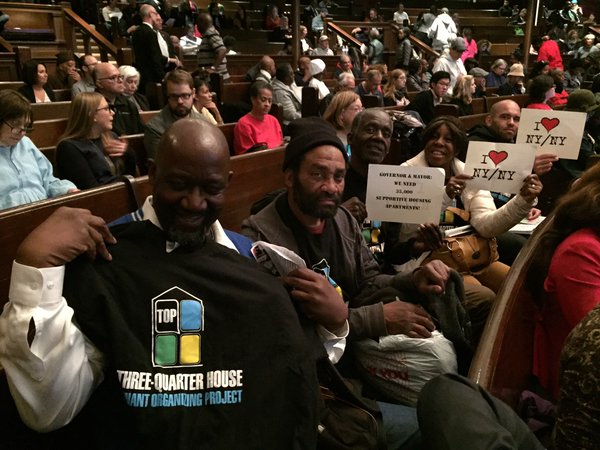

At a recent NY/NY event at New York Society for Ethical Culture, via @TOPnyc

I usually approach the New York Society for Ethical Culture, where I serve as clergy leader, from Central Park West and look across the street from the park at the words carved into stone on the corner of our meeting house: "Dedicated to the ever-increasing knowledge and practice and love of the right."

Today "the right" is used to identify a socially conservative political stance, but in 1910, when these words were inscribed, it referred to ethics and a community determined to do the right thing in challenging times. Since founding the Society in 1876, members have sought ways to make the world a better place for everyone, beginning with improving living conditions in tenement housing and forming settlement houses that built affordable housing.

Nearly 140 years later, we still live in challenging times and continue our commitment to treating the homeless as our neighbors and working for affordable housing. Today, we have many partners in the Interfaith Assembly on Homelessness and Affordable Housing. In addition to providing shelter for homeless women for over thirty years, the Society hosts events that gather advocates from across the city and state to work in concert for affordable housing.

The latest event, held on October 23, "Campaign 4 NY/NY Housing," called upon Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio to work together and with the more than 200 state and local organizations calling for 30,000 new units of supportive housing over the next ten years for our most vulnerable neighbors: the homeless, now about 60,000 people who sleep in city shelters or on city streets every night. This statistic includes over 14,000 families with nearly 24,000 children; and it has reached the highest levels since The Great Depression of the 1930s.

How did this happen? Research compiled by the Coalition for the Homeless from data collected by the city Department of Homeless Services and Human Resources Administration shows that the primary cause of homelessness is lack of affordable housing, triggered by eviction and job loss, severely overcrowded and hazardous housing conditions, domestic violence, and serious mental health disorders. This social "perfect storm" has put a strain on the resources of private and public organizations throughout the city, especially in Manhattan, which holds nearly 60 percent of our unsheltered homeless.

How do we address this community reality? Mayor de Blasio, whose administration recently announced a plan to create 15,000 supportive housing units over fifteen years at a cost of $3 billion, will face pushback from neighborhood leaders who oppose the siting of those units. But, it is absolutely essential. Negotiations with Governor Cuomo over a new "New York/New York" deal, the much-anticipated fourth city-state supportive housing plan, are at an impasse. Local advocates, including we clergy in the Interfaith Assembly, are frustrated with the de Blasio-Cuomo feud and have written to both politicians imploring them to stop playing politics and start acting like the leaders we elected them to be. This is an ethical issue that demands immediate and non-egotistical action.

In the meantime, how can we be the good neighbors that so many of us want to be? NYPD Commissioner Bratton has urged New Yorkers not to give money to homeless people living on the streets, and Mayor de Blasio has said that the best way to help is to donate to nonprofit organizations serving homeless people. I agree, we should donate to shelters and organizations, and I hope that more people will volunteer at shelters, including ours. But I see no harm in making a direct and personal donation to individuals. Offering money can be awkward, but offering a piece of fruit, a wrapped sandwich, or a coupon to a restaurant is appreciated. We can also provide information about local sites that offer meals and hot showers. Interfaith Assembly on Homelessness and Housing offers a helpful resource that can be referenced, printed, or circulated by email or on social media.

The most important way of helping is to see others as people worthy of dignity and respect. Bear in mind that many people who live in shelters are employed, but their income isn't enough to cover housing; they are not lazy and useless.

When I leave the Society for Ethical Culture's meeting house, I always stop to read at least one passage from the "sacred" text mounted on the north wall of our lobby: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is a document that set out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected, and was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on December 10, 1948, in the wake of World War II.

Today I read very closely Article 25(1): "Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control."

No doubt some New Yorkers have become numb to seeing homeless people on our streets. Homelessness in our city has nearly doubled in the last decade, and "compassion fatigue" can occur, especially if we feel there is nothing we can do to make a difference. But when we acknowledge our common humanity, encounter people with an open heart and gentle words, educate ourselves about the resources available in our communities, and resolve to act, we can make a real difference in the lives of our neighbors.

***

Dr. Anne Klaeysen is a Leader of the New York Society for Ethical Culture.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Time for New York to Cut the Coal

Sen. Krueger, the author, visiting a school (photo via @LizKrueger)

In October, Governor Cuomo stood alongside former Vice President Al Gore and reiterated his commitment to reducing New York's carbon emissions 40 percent by 2030, as well as his willingness to phase out New York's coal-fired power plants. These were laudable statements in a high-profile public forum. Unfortunately, these goals will remain out of reach as long as the state continues to send the wrong market signals by requiring New Yorkers to underwrite dirty and uneconomical coal plants through increased electricity bills.

With just weeks left before global climate negotiations begin in Paris, now is the time for the Governor to make an enforceable commitment to phasing out coal-fired power by the end of the decade and ensuring a just transition for workers and communities dependent on coal.

New York's four remaining coal-fired power plants – Cayuga, Dunkirk, Huntley and Somerset – contribute 13 percent of New York's electricity sector carbon pollution. They no longer make a profit, yet the state has been keeping them operational at a cost of hundreds of millions of dollars.

The Dunkirk plant has received $90 million to continue operating through the end of 2015, and the Cuomo administration approved up to another $200 million over the next ten years; the Cayuga plant is receiving $155 million to continue operating through 2017, and has recently asked for an additional $145 million. These costs are paid for by local electricity customers, with plant owners pocketing the profits. Yet according to the utilities National Grid and NYSEG, transmission upgrades, many of which will be needed regardless of whether the coal plants remain operational, could address reliability issues at significantly lower cost when the plants close.

Taking these plants off-line will get us one third of the way to the state's carbon reduction goal while safeguarding the thousands of New Yorkers threatened by dangerous coal-fired pollution. But the state is currently sending market signals that directly contradict the Governor's emission reduction and renewable energy goals.

Coal plant owners are coming to expect that they can rely on New York's energy customers to keep their outdated and unnecessary plants on life support, a fact made clear by the recent request from Beowulf Energy to purchase Cayuga and Somerset. Time after time our government has required New Yorkers to foot the bill for dirty energy rather than investing in transmission upgrades that could get ahead of the curve on local reliability issues at a fraction of the cost.

New Yorkers are ready to pitch in to help transition away from coal. There is strong public and political support for a responsible transition plan for coal reliant communities - one that would require only a small portion of the money currently being spent. Earlier this year I joined over one-third of New York's legislature in signing a letter, authored by Assembly Member Barbara Lifton, urging Governor Cuomo to end coal subsidies and create a thoughtful statewide transition plan. Next, we will rally with elected and other allies, including the Sierra Club, as we continue to push for a smart, responsible path forward.

We are nearing a tipping point when it comes to the damage we're doing to our climate. As we approach the United Nations Conference on Climate Change in Paris, New York is poised to be an international leader in the fight against climate disruption. If we stop clinging to policies that keep our energy sector stuck in the past, the Empire State has the potential to lead the world in the bold transition to a clean energy economy. Governor Cuomo could lead us there by speeding up his commitment to phase out coal-fired power and taking a key step toward ensuring carbon pollution becomes a thing of the past.

***

Liz Krueger is a State Senator representing Manhattan. She is on Twitter @LizKrueger.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A City We All Want to Live In

Mayor, PC (photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office)

In 1992, the Manhattan Institute's quarterly policy magazine, City Journal, published a special issue focused on "The Quality of Urban Life." At the time, New York was a dangerous, dirty, and purportedly ungovernable city. "Cities should be comfortable places," wrote the magazine's then-editor Roger Starr before setting out an ambitious agenda to reclaim New York's public spaces. In the years to come, New York followed through, cleaning up the streets and subways, reducing crime dramatically, and prospering.

Victories are never permanent, though, and serious challenges remain. Education tops the list. Strong schools are crucial for cities looking to attract and retain families. Yet New York's schools still suffer from many of the same problems that plagued them in 1992: union contracts that favor teacher seniority over performance; a lack of choice and alternatives for parents; and lax standards and curricula in the classroom.

We can point to signs of progress. With the encouragement of the Giuliani and Bloomberg administrations, charter schools have proliferated. The first city charter opened in 1999; more than 200 now operate in the city, and they've put up strong results. Black and Hispanic charter students outscore their counterparts in traditional district schools in both math and English language arts. Yet charters remain a too-small portion of the more than 1,800 schools that make up the public school system.

The teachers' unions remain powerful, but they face significant legal challenges. A case currently before the Supreme Court could put an end to the mandatory dues collection that makes public-employee unions so politically formidable in New York and elsewhere around the country. Common Core, though controversial, is establishing a more rigorous set of academic standards.

These are positive developments for the city's schoolchildren and their families, but New Yorkers deserve more from their education system—namely, greater levels of choice, competition, and access to information. With this goal in mind, the Manhattan Institute helped to launch SchoolGrades.org, which provides a transparent assessment of public school performance across the country. More such resources, combined with an embrace of flexibility in education by Albany and City Hall, could go a long way.

The remarkable improvement in New York City's quality of life since the 1990s has attracted new residents, an encouraging development but one that has multiplied demands on the city's aging infrastructure, including its public transportation system. Subway ridership hit a 65-year high in 2014 and is up over 60 percent from 1992 levels.

Major train lines—such as the 4, 5, and 6— regularly run at more than 103 percent capacity during peak ridership periods, as anyone who has crammed into a packed train during rush hour can attest. And the stations themselves are increasingly dismal, blighted by pooled water, litter, and crumbling walls.

Successful cities must plan for the consequences of success. This means building and maintaining the infrastructure to support new residents. A subway system unprepared to transport those people could quickly run into crisis.

Our political leaders must do better. Governor Andrew Cuomo once again stalled the few new stations on the long-planned Second Avenue subway. While three stops are slated to open next year on the Upper East Side, we're decades away from completing this vital project.

Concern over public order has also crept back into headlines. We're still a long way from the chaos of the 1980s and early nineties, but there's reason for concern. The rising numbers of vagrants, the more aggressive panhandlers making their way into Times Square, the growing push for decriminalizing "minor" offenses such as public urination and fare-jumping—these and other trends suggest a city on the verge of forgetting just how much effort it took to revive itself two decades ago.

We must avoid what longtime Manhattan Institute senior fellow Fred Siegel described in 1992 as a "collapse of common standards" in our city. When ordinary citizens retreat from public spaces, it leaves a vacuum to be filled by the forces of disorder. We know where that leads: to a city that repels people and businesses.

Whatever problems persist in New York City, we must remember how far we've come. The reformers of 1992 sought to rescue a city on the brink. This week, during the Manhattan Institute's quality-of-life week, we call on all New Yorkers to help preserve the city's gains for future generations.

***

Lawrence Mone is President of the Manhattan Institute. Read City Journal here and follow the Manhattan Institute on Twitter @ManhattanInst.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

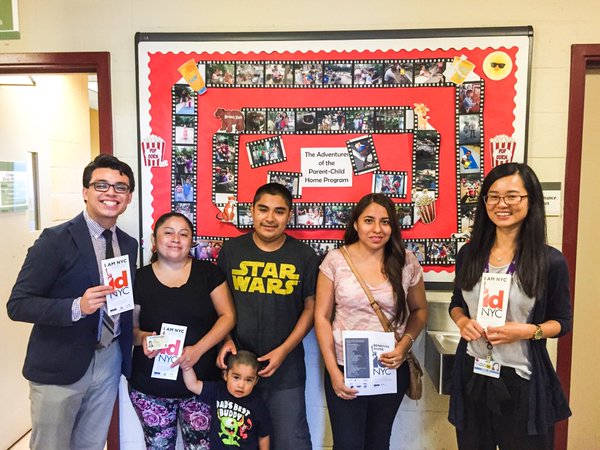

IDNYC Cardholders Await Assurance Ahead of Year Two

photo via @IDNYC

In September 2014, Mayor de Blasio held a major press eventaround the city’s IDNYC program that centered entirely on one benefit of the new municipal identification card: the free one-year membership offer at 33 museums and cultural institutions part of the Cultural Institutions Group (CIG). In the accompanying written announcement, 16 city and community leaders were quoted praising the program, especially this cultural enrichment aspect. One said it “has the potential to transform lives.”

And indeed it surely has, as many New Yorkers have jumped at the perk - over 30,000 IDNYC cultural memberships were accessed as of the end of July, according to the city. The transformative potential of the ID is not entirely nested in a cardholder’s newfound ability to visit the Basquiat exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum over the summer, of course. Identification is a fundamental societal resource. In fact, the city announced at the end of July that over 400,000 IDNYC cards had been granted. It is this number, and the real target populations of the program - undocumented immigrants, people lacking stable housing, and others - that are indicative of the importance of the program. But the larger-than-expected enrollment and the vulnerable populations involved are indicative of how important it is that the city clearly indicate what year two of the program will look like.

Thus far, there has been little information from the mayor or his Office of Immigrant Affairs (MOIA), which has led the IDNYC program. As Thanksgiving approaches, it is time that cardholders are informed about its future. While MOIA representatives have said that the program will continue to grow and no one should feel at risk of losing the card’s basic benefits, cardholders would surely feel more at ease hearing details from their mayor.

New Yorkers realize how important identification is, though many who have had a driver’s license since being a teenager may need a reminder. ID is required to perform a number of seemingly innocuous tasks: enter certain spaces (e.g. municipal buildings and schools, to access city services), apply for an apartment lease, open a bank account, get a public library card, sit for the high school equivalency exam, and, during encounters with the NYPD, receive a summons or desk appearance ticket in lieu of transport to a police station.

Basic identification is a less flashy, but essential benefit of the municipal ID; the ID gives a wide variety of city residents (in particular, undocumented immigrants, homeless individuals, transgender individuals, and victims of domestic violence in non-stable housing situations) a means to perform a number of life-stabilizing tasks. In addition to providing a vehicle to access services and material resources, the ID itself is proof of societal membership.

This notion of “membership” is especially important for actualizing some of the less visible benefits of the municipal ID program. The card provides formal recognition, which can command respect from others, particularly during encounters with the police, and instill a sense of self-respect among cardholders who enjoy fresh opportunities to take advantage of resources and services. Respect is not just “the golden rule;” in the eyes of established social justice theorists, “respect” is actually an essential dimension of well-being.

The municipal ID provides each cardholder with a sense of everyday belonging in society and entitlement to access available resources and support. These phenomena (“belonging” and “perceived availability of support”) are two mechanisms by which physical and psychological well-being can be improved, according to social science research. Furthermore, the public health tradition of inquiry, endorsed by the Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Sciences and the World Health Organization, known as the “social determinants of health” suggests that the perception of greater resource availability is likely to increase utilization of accessible support and positively impact health. How? With more resources (such as money, knowledge, and social connections) people are better able to buffer against adverse health events and prevent health shocks from being catastrophic if/when they do happen to occur.

With such potential and obvious resonance with de Blasio’s OneNYC vision for a “strong and just” city, the future of the IDNYC program and the longevity of its benefits should not be murky this late in the year.

Contacted about the program and its future, Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs Commissioner Nisha Agarwal said in a statement, “From its launch, Mayor Bill de Blasio and his administration have said that the IDNYC program and its utility will grow over time. IDNYC will continue to progress and serve even more New Yorkers in Year Two. We look forward to sharing more detailed news before the start of the second year of the program.”

The card and benefits are free, between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2015, for anyone that can meet the proof of identity and city residency requirements (which make allowances for non-stable housing situations). But, puzzlingly, there has been little public discussion about what happens come January 1, 2016. Will the card and its benefits remain free? Will the hallmark CIG promotions lapse? The elimination of the CIG benefit could have potentially deleterious effects, given that it was a strategic move to make the card universally appealing (and reduce potential for associated stigma). Most importantly, will the municipal ID continue to be, or even expand its usefulness as, formally recognized identification? Or will it become less useful over time? There are already several restrictions on the utility of the card (it can only be used at certain banks to open accounts, it does not serve as proof of identity for a driver’s license, does not authorize receipt of public assistance benefits, and cannot be used as identification during plane travel).

Certainly, there are life-changing benefits associated with this municipal ID program, and as the largest in the country (with those 400,000 cardholders as of July), this program is in urgent need of a long-term plan that ensures: the municipal ID continues to be regarded as formal and useful identification, cardholders maintain essential benefits, and the card remains universally appealing – such that cardholders are not required to inadvertently accept a potentially isolating and stigmatizing “other” status.

Like many New Yorkers, I eagerly await information about year two of IDNYC.

***

Lauren A. Haynes is an MPH candidate studying health policy and social determinants of health at Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health. She has also worked for New York City’s public hospital system.

Improving CUNY’s Equity and Efficiency: Requiring Some Tuition for All

Faculty protest (photo: @PSC_CUNY)

CUNY faculty has not had a contract for six years. While interested parties can disagree over how big raises in the new contract should be, with a new contract, college costs will increase so there should be serious discussion of where the funds will come from.

Currently, only 45 percent of CUNY costs are paid for by student tuition because two-thirds of CUNY students have no tuition obligation. Unfortunately, CUNY administrators and faculty are united in their commitment to having lower-income students avoid taking out any student loans. Indeed, when need-based grants briefly fell $100 below CUNY tuition, one campus president found funds to make sure that no student would have that meager tuition obligation.

Like Hillary Clinton, I believe that every full-time CUNY student should be obliged to pay a modest sum annually that is not covered by need-based grants. In response to Bernie Sanders support for free public colleges, she said, “Students should have to work during college, like I did, to help earn their free tuition at public colleges.”

Requiring modest obligations is not only equitable but will increase the effectiveness of the resources provided; recipients will take their commitments more seriously when their own resources are required. This was the philosophy of Julius Rosenwald. During the Great Depression, he funded the construction of almost 500 black schools in the Deep South only on the condition that the local communities chipped in. These schools enrolled one in three black southern children.

A current example is a CUNY hearing clinic that offers a program to improve the performance of individuals who have purchased hearing aids. Virtually all clients who completed this program felt that it was most valuable. When the clinic did not charge, clients invariably missed many sessions but not after it began charging a nominal sum: $100 for ten one-hour sessions.

This link between modest charges and effort may partially explain what appears to be the dismal performance of CUNY schools. According to a new report from the Department of Education, CUNY students have consistently lower workforce earnings than should have been expected.

As reported in The Economist, for eight of the nine CUNY four-year colleges surveyed, among students who received federal aid, earnings during the first ten years after graduation were lower than what should have been expected given measures of student “entering skills,” quality of the college attended, and job market in the college's vicinity. For my school, Brooklyn College, students earned $3,276 less annually than the expected earnings of $47,776. When individuals receive uncharged services, many do not use them effectively.

These policies also create other inefficiencies. A vast majority of entering students fail at least one of the skills assessment exams, requiring remediation. CUNY Start provides these students the option of taking a more intensive set of remediation courses before entering the community colleges. CUNY Start has success rates more than double the community colleges and yet its use has been limited.

Unlike students who take their remediation after entering the community colleges, CUNY Start students do not qualify for need-based grants. As a result, CUNY Start charges students only $75 for their remediation courses. This makes it an expensive alternative because CUNY has to make up the difference between the actual cost and the meager payments required.

In addition, CUNY is unwilling to require even the most weakly prepared students -- those who have failed all three of the skill assessment exams -- to go into CUNY Start before entering the CUNY system. This requirement would undermine the longstanding policy that entrance into CUNY community colleges is an entitlement for anyone with a high school or GED degree.

A second example of how free tuition for poorer students leads to inefficient policies is how certificate programs are treated. For many at-risk students, less demanding certificate programs might be the best option. If properly selected, they provide valuable vocational skills. CUNY offers these programs through its continuing education division so that students can avoid going into the for-profit sector where they may be victimized by unscrupulous schools.

I spoke to some counselors who advise individuals after they successfully completed their GED. While many have difficulty when entering the community-college system, she did not counsel any to seek certificate programs. One important reason was certificate programs are non-college credit courses, so students do not qualify for need-based grants. As a result, students would be responsible for the modest sum that CUNY charges. This leads more students toward community college as opposed to the certificate programs that may better suit them. Once more, the unwillingness to allow for even a small student debt causes the best educational policies not to be chosen.

I would recommend that whatever the increased cost of the new CUNY faculty contract, it should be passed along to students as a tuition increase. At the same time, there should be no increase in need-based grants.

Instead, student loans should make up the gap between grants and tuition. In addition, CUNY should make mandatory that any student failing all three skill assessment exams be required to enter CUNY Start rather than being able to go immediately into the community college system; and charges therein should be increased modestly.

These policies will reduce the current inequities and inefficiencies that exist in CUNY and thus should be supported by all.

***

Robert Cherry is Stern Professor at Brooklyn College and CUNY Graduate Center.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Cuomo and De Blasio Must Create Affordable Housing for the Homeless

Back in June, sixty people went to jail after demonstrating in front of Governor Cuomo's office, demanding stronger rent laws. We were among them. Despite the governor's claim that he made the "strongest improvements to rent laws ever," he failed, at that critical moment, to strengthen tenants' rights, choosing instead to stand with the landlords and the real estate industry. It was a devastating blow to the 2.5 million rent-regulated tenants in this city, and to the broader fight for preservation of affordable housing and protecting communities from destruction by gentrification and displacement.

For tenants and their allies, it is about acting on the belief that housing is a basic human right of all people. That is why we went to jail, and why we would do it again.

The 57,000-plus New Yorkers currently languishing in our city's shelters, and on city streets, should all have homes. The governor's failure to deliver better rent laws will inevitably exacerbate the homelessness problem, as more low-income tenants live one rent increase away from losing their apartments.

The rent burden is steadily increasing on New Yorkers across the five boroughs, and Cuomo's unwillingness to reform and strengthen our broken rent laws will hasten the loss of thousands of rent-regulated apartments.

The only way to address our city's homelessness crisis is through the creation of real affordable housing for the homeless. That requires, in part, a proactive affordable housing preservation strategy, including stronger laws to preserve existing affordable housing.

To make that happen, we need action by both Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio.

The mayor must include the homeless in his ambitious affordable housing agenda, and the governor must fix the rent laws to repeal vacancy deregulation and end the eviction bonus.

The mayor and the governor must work together to create desperately needed supportive housing, as well as rental assistance programs to move people out of shelters into permanent affordable housing. The mayor has made some effort on the latter, but needs to significantly increase that work.

It's long past time for Cuomo and de Blasio to jointly address our city's homelessness epidemic and work toward ensuring that every New Yorker has access to a decent, safe, and affordable home.

There is a growing movement of tenants and homeless New Yorkers standing together to demand that the governor and mayor address the collective housing needs of the most vulnerable New Yorkers.

Tenant organizing, stronger rent laws, and the preservation of existing affordable housing are crucial elements of the broader effort to end homelessness in our time.

Indeed, the fight for affordable housing is part of the larger fight for a truly equitable city and state where no one, regardless of income, background, or circumstance, is denied access to a livable and affordable home.

The moment for real leadership from Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio has arrived.

***

Katie Goldstein is Executive Director of Tenants & Neighbors. Ava Farkas is Executive Director of Met Council on Housing.

Game Changers for JFK International

JFK (photo via Department of Homeland Security)

With the strong encouragement of Governor Andrew Cuomo, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey is now hosting an international design competition to create a new master plan for JFK Airport. This plan will guide improvements for JFK runways, terminals, cargo needs, public transportation access, and other infrastructure. Rather than allowing the governor's office and airport officials to make decisions behind closed doors, the public needs to nudge the Port Authority to develop the airport's master plan via open discussions, increasing the likelihood that the planning will benefit the environment and the general public.

Based on how the Cuomo administration has been able to expedite the replacement of the Tappan Zee Bridge and the redesign of LaGuardia Airport, here is what to expect if there is no public process. First, Cuomo announces a project and a competition. Then, the designated government agency issues a Request for Proposals. The governor's office and the agency subsequently select a winner, promise financing, and closely manage any required public participation, political resistance, and permit reviews. The planning concludes with the agency selecting a single contractor to both design and build the project.

This top-down process might not be the best way, however, to create projects that resolve longstanding issues often at the base of the pressure for new infrastructure. The new Tappan Zee Bridge, for instance, is finally under construction, but it will not address long-term transportation or environmental issues in the region. Building quickly, often at great cost, isn't the only way to create first class infrastructure.

Here are five suggestions that may or may not be under consideration by the Port Authority, but would significantly upgrade the airport and New York's economy in the long term:

1. Subsidize the AirTrain. The AirTrain, which currently carries more than 45,000 people per day, can be even more successful. It really doesn't make much sense that travelers ride the AirTrain for free between terminals and park-and-ride lots, pay $5 for a short AirTrain ride to the Howard Beach or Jamaica subway stations, and then only pay $2.75 for a much longer subway ride (A, J, Z, or E) to Manhattan and other city destinations.

Since we are not likely to get a "one seat" ride to from the airport to Manhattan (or anywhere else in the city) in the foreseeable future, reducing the $5 fare would be a game changer for many travelers, especially for the airport's 37,000 employees, many of whom currently drive or take a slow bus. The Port Authority could add surcharges for taxis, Uber, and other ridesharing services that would generate revenue to lower the $5 fee and also help alleviate congestion and pollution on the Van Wyck Expressway, the main highway used to carry goods and people to and from JFK Airport.

2. JFK/Jamaica Bay Partnership. The Jamaica Bay portion of the Gateway National Recreation Area and JFK Airport have stood in tension for decades. The recreation area was created in large measure to protect Jamaica Bay from JFK expansion and pollution. Yet the plans to protect the recreation area were made in an era of robust government park budgets and without any sensitivity to climate change. As it is, Jamaica Bay has yet to achieve its promise as envisioned by either Robert Moses (who created the original parks there) or the National Park Service, which protects and operates Gateway.

The bay is still a prime habitat for migratory birds and other wildlife, but the bay's salt marshes are washing away. Of the 16,000 acres of marsh that existed in the 1800s, according to The New York Times, less than 1,000 acres exist today. Some of the loss is due to filling in of marshes for JFK and other surrounding urban activities, but more contemporary losses are usually blamed on water pollution, wave action, and rising sea levels. Loss of marshes not only reduces habitat space; the open waters make the surrounding neighborhoods and the airport more vulnerable to flooding.

The city has done its part to upgrade water quality and close landfills. The Port Authority, under regulatory pressure, has remediated underground oil pollution, prevented new leakage, and implemented procedures to reduce pollution from ongoing airport activities such as de-icing planes and runways. The same comprehensive approach to challenges is not found at the National Park Service, which has failed to respond to the tens of thousands of acres of wetland loss in any substantive matter. With higher priorities out west and elsewhere, and tight budgets, we can't expect much more from the federal government.

The Port Authority has resources for the massive action necessary to restore marshlands and further improve water quality. In exchange for Port Authority funds for marsh restoration, the authority should be able to study, and eventually build, moderate runway extensions along the edge of Jamaica Bay that would boost capacity and reduce delays.

3. Green the Airport. Air travel is one of the major global contributors to climate change. For many non-driving New Yorkers, flying is the largest part of their annual carbon footprint. The Port Authority's master plan for JFK Airport should include a program on site that will reduce the airport's energy footprint dramatically.

Solar panels could be installed over the parking fields that would reduce ground temperature and generate energy for operations. Solar panels or green roofs could also be installed on the roofs of the terminals, hangars, and other buildings. "Greenwalls" (plants mounted on vertical wall frames) could be attached to the large (and frankly, ugly) walls of parking garages, making for a more attractive landscape. These greenwalls also absorb sound, filter air, and reduce temperatures around them. An aggressive rainwater collection and landscaping program could further reduce pollutants draining into the bay.

Greening JFK airport not only provides local economic and environmental benefits, but as the metropolitan area's gateway to the world, a green airport would symbolize New York's commitment to protecting the planet.

4. Super Silent Planes and Noise Mitigation. JFK Airport will not be able to take full advantage of the Federal Aviation Administration's new air control system unless the Port Authority becomes a national leader in aircraft noise control. Thanks to new satellite technology, the new NEXTGEN air control system will allow planes to fly closer to each other both horizontally and vertically. But, neighborhoods near JFK Airport are already in revolt over the prospect of even more plane noise.

Decades past, the Port Authority was a major force behind quieter jets, controls on the supersonic Concorde plane, and retiring old aircraft. Indeed, thanks in part to the Port Authority, modern jets are much quieter than earlier versions. The third generation Boeing 747-8, for instance, is 30 percent quieter during takeoff and landing than the older Boeing 747-400; even though the new plane is longer, wider, and taller. But we only get those noise reduction benefits if airlines buy and use those planes, and not all airlines do. The Port Authority needs to encourage the airlines operating in New York to use only the quietest planes available.

The Port Authority needs to send a strong message to airlines and aircraft manufacturers that they need to accelerate the jump to even quieter planes. The authority has leverage since it operates three airports that rank in the top twenty of America's busiest airports. The planning for these new planes is happening now, but because of the long period between design and implementation, the realization of these super quiet planes will take years, and perhaps decades. New Yorkers can't wait that long, and neither can the Port Authority.

5. Parkway Cargo Vehicles of the Future. JFK suffers from having only one all-highway truck route to its air cargo areas—forcing all trucks onto either the Van Wyck Expressway or neighborhood streets. Congestion on the Van Wyck and the Long Island Expressway (the only other east-west highway on Long Island for trucks) has hurt JFK's once dominant cargo business. Trucks on neighborhood streets undermine quality of life in many surrounding neighborhoods.

Why does New York have such a strange system of roadways? Robert Moses created lovely green parkways such as the Grand Central, Belt Parkway, and Southern State that are still mostly truck free. And neighborhoods along those roads aren't likely to welcome any additional commercial traffic. The decision earlier this year to allow 53-foot trucks on city expressways, and the reconstruction of the interchange at Kew Gardens, will benefit business and overall traffic flow, but this change isn't enough to get shippers to rethink the extra cost of doing business at JFK or on Long Island.

As the City of New York did with its Taxi of Tomorrow, the Port Authority should sponsor a contest by truck manufacturers to design a vehicle that meets the height restrictions of parkway overpasses, has sufficient cargo storage capacity, runs quietly (perhaps a hybrid or natural gas) and is aesthetically pleasing. These distinctive, and perhaps futuristic, New York parkway cargo vehicles could help boost JFK's declining air cargo business—a key to the region's future.

Since there are many routes to creating a world class airport, the Port Authority should engage the public by describing possibilities, explaining the constraints, and helping to develop creative ideas.

***

by Nicholas D. Bloom and Philip M. Plotch

Bloom is associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology where he is also Chair of Urban Administration and Interdisciplinary Studies. He has written many books including The Metropolitan Airport: JFK International and Modern New York and the forthcoming edited collection from Princeton University Press, Affordable Housing in New York: The People, Places, and Policies That Transformed a City.

Plotch is an assistant professor of political science and director of the Masters in Public Administration program at Saint Peter's University in Jersey City. He is the former director of World Trade Center Redevelopment and Special Projects for the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and the former manager of planning for New York's Metropolitan Transportation Authority. He is the author of Politics Across the Hudson: The Tappan Zee Megaproject.

Reality TV Has No Place in Emergency Rooms

Council Member Garodnick, the author, at a press conference (photo: @transalt)

It's hard to make a serious argument that we should be filming sick patients in our emergency rooms without their prior written consent. And yet, that is exactly what popular reality television shows like "NY Med" do on a regular basis.

ABC -- which has produced and broadcasted a surprising number of these shows in cities across the country-- has defended this practice, saying that they "have heard many stories of people who were inspired to go to medical school, to become nurses or paramedics, or to head into particular specialties like trauma or transplant surgery, after watching our show." That may be, and the choice to join the medical profession is a noble one, but it should not rely upon the infringement of patients' right to privacy and confidentiality for promotion.

We're not talking about "Grey's Anatomy" here; while reality television shows set in hospitals play on natural human interest in drama, suspense, hope, and loss like scripted shows do, the stories portrayed on these screens are real events happening to people we know, not staged scenes with paid actors.

ABC's NY Med even aired an episode documenting the treatment and eventual death of Mark Chanko, without his consent, to the horror of his wife and children. In 2011, Mr. Chanko was struck by a sanitation truck and was sent to the emergency room at New York Presbyterian Hospital. Mr. Chanko's family not only had to suffer the terrible loss of a husband and father, but three years later, they experienced a brutal and unexpected reminder when they happened to catch the episode and recognize personal details.

In response to concerns raised by members of the New York City Council, privacy advocates, and those moved by the story of the family of Mark Chanko, the Greater New York Hospital Association (GNYHA) on behalf of its members, a few months ago committed to not allowing filming of patients without their prior written consent. This move effectively puts an end to emergency medical reality TV shows in New York City.

Unfortunately, these shows persist in other cities, and patients are being filmed for reality television in Boston, New Orleans, Houston, and emergency rooms across the country. These shows have the same privacy concerns that plagued "NY Med," yet the genre has seen steady growth, and the invasion of privacy has continued unabated, despite calls from medical professionals to shut the shows down.

In fact, the American Medical Association (AMA) in 2001 established guidelines for filming patients for public viewing, which requires that patients give their informed consent prior to being filmed. The AMA Code of Medical Ethics considers filming prior to obtaining a patient's consent to be "a violation of the patient's privacy."

We cannot allow such disregard for patient privacy to continue. Filming patients without consent is both medically and journalistically unethical, and incredibly upsetting for families who have experienced the loss of a loved one.

Elected officials and leaders of medical communities in all media markets should join New York in recognizing that the practice of filming patients for reality television shows without their consent has no place in our emergency rooms.

Personal tragedies are not fodder for reality TV, and American hospitals have a responsibility to put a stop to these invasive shows. I look forward to continuing this conversation with an eye towards reaching all communities whose rights are being violated in the name of entertainment.

***

Dan Garodnick has represented the Fourth District in the New York City Council since 2006, and chairs the Economic Development Committee. On Twitter @DanGarodnick.

***

Have an op-ed for Gotham Gazette? E-mail an idea or a draft to editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.