Happy New Year Budget

City budget news gets better and better, setting the stage for a fresh kind of budget debate, beginning later this month when the mayor releases the preliminary budget for fiscal year 2007 (which begins in July, 2006), and the four-year financial plan that accompanies it. Both Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the newly elected New York City Council Speaker Chris Quinn begin in a happy budget place, just three years after the city faced budget deficits in excess of $6 billion.

The mayor’s November budget modification underplayed how good things are, at least in the short run, according to several fiscal monitors’ reports released in December. For instance, the report from the office of the state deputy comptroller for New York City estimates that the city’s 2007 budget deficit could be as little as $645 million, not the $2.25 billion deficit anticipated in the mayor’s November plan. In the longer term, however, little has changed in terms of the structural imbalance in the city ’s financial plan; the report also projects deficits averaging about $4 billion in 2008 and 2009.

Rise In Revenue, Cut In Pension Costs

The bright outlook for next year stems not only from the unanticipated tax revenue gains since June, but from likely changes in the city’s contribution to the city pension funds that were not included in the November modification. The fiscal monitors expect the January plan to reflect those changes –- which stem from a series of new calculations about what the city needs to spend each year to meet its pension obligations.

The pension changes will, in the short term, save over $800 million in city spending in 2007 and about $550 million or more in 2008, according to reports by both the state deputy comptroller and the state financial control board. These savings will be offset in part by higher contributions in subsequent years -- $290 million in both 2009 and 2010, according to the state deputy comptroller.

The Independent Budget Office in its December fiscal outlook, “An Improving Fiscal Climate Presents New Challenges,”(in pdf format) sums up the current context: “Today’s fiscal climate has changed dramatically, though it brings a new set of potential challenges as public acceptance of the need for austerity may shift towards calls for tax cuts and increased spending.”

Taxes

Of course one good reason the longer-term budget problems remain is that the new calendar year begins with a very large, previously determined tax cut. The two top personal income tax rates (4.25 percent and 4.45 percent), on the city’s wealthiest residents –- the most progressive of the budget-gap-closing actions in 2003 -- were eliminated at the end of December 2005, at a cost of approximately $500 million a year of lost revenues. And yet another tax cut has already been set, the $400 property tax rebate that goes to residential owners again in 2007 -- and will cost the city over $250 million in lost revenues.

In this context, the mayor’s recent call for a reinstatement of the commuter tax, which would get back roughly $500 million of recurring revenues, is a bit disingenuous, since the mayor and the new council speaker stand a much better political chance of restoring the top personal income tax (or PIT) rates on residents than the commuter tax, which is controlled by the state legislature and governor.

Property taxes and property transaction (mortgage recording and property transfer) taxes currently represent over 45 percent of all tax revenues. None of the monitors foresees the transaction tax revenues remaining at this year’s level, but the property tax remains the solid base of the city’s revenue system. The Independent Budget Office estimates that from 2007 to 2009, the property tax will average 7.5 percent growth each year, rising from $12.4 billion in 2006 to $15.4 billion in 2009.

Overall, the budget office estimates tax revenues will average only 3.7 percent growth from 2007 to 2009. The faster growth in property taxes means that property taxes alone in 2009 will represent 43.5 percent of all city tax revenues, versus 39 percent in 2006. This shift in tax burden to the property tax is another reminder that reform of the city’s bizarre and unfair property tax system should be a priority in the mayor’s second term.

Spending

If the $750 million in tax cuts already in place satisfies the tax-cut side of next year’s budget debates (unlikely), then all the action -– particularly from the newly reconstituted city council -– will be on the spending side. Here the basic message of the Independent Budget Office’s December report is that, on average, spending on city agencies has been essentially flat for the past two years, and in the mayor’s current four-year plan will remain so until 2009.

The flatness of agency spending is often obscured by the steady rise in overall city spending. City-funded expenditures, for instance, will rise by an average of nearly five percent a year from 2007 to 2009. But the bulk of that spending is in two general areas: 1) mandated spending for health insurance and other fringe benefits for city workers, pension costs, Medicaid, and debt service on the capital budget, and 2) increased wage costs from the recent (and anticipated future) labor agreements.

The two biggest sources of budget growth are debt service and health insurance and other fringe benefits. Debt service will rise an average of 11 percent a year from 2007 to 2009, to $5.8 billion in 2009 –- largely from the mayor’s ambitious capital plan for school construction and other projects. Health insurance and other fringe benefits will grow six percent a year during the same period, reaching $3.9 billion in 2009. (Medicaid spending growth has slowed somewhat -- an average three percent a year increase through 2009 -- in large part because of a new cap introduced by the state on the local share of Medicaid spending.)

Leaving out mandated and wage costs, the Independent Budget Office sees agency spending from 2007 to 2009 rising less than one percent per year, far less than the rate of inflation. The report points out that there have been neither large spending initiatives nor major cuts in spending over the past years, and the mayor’s current plan promises nothing more.

Hope For Fresh Thinking for 2007

There is a happy disagreement over how high the budget surplus will be by the end of this fiscal year in June, with estimates ranging from $1.7 billion to $2.8 billion. The deputy comptroller raises an interesting point, however. Whatever the amount of the surplus, it depends entirely on the surplus that was carried over from 2005 to balance this year’s budget. Without that one-time surplus, there would be a big current-year operating deficit.

The big problem, in other words, is that the city keeps using huge one-shot revenues to balance its budget, masking what the deputy comptroller calls “an underlying structural imbalance between recurring revenues and expenditures.”

The Independent Budget Office is a bit more optimistic. It says the current improvement in the city’s fiscal outlook is “the result of both fiscal design and economic fortune.” The city has moved toward “a closer match between recurring revenues and recurring expenditures.”

After four years of narrow focus on fiscal crisis management, education management and governance, and a failed West Side stadium project, it’s a good time to use the city budget for fresh policy thinking. Countless ideas abound within and outside government on such issues as tax reform, human service and health policies, and broad-based housing and economic development.

The Independent Budget Office report, indeed, anticipates new budget pressures and seems to imply this will be threatening to the improved fiscal outlook. But one can hope that a term-limited mayor and a term-limited council speaker will welcome a debate on a mutual legacy that serves fiscal as well as social and political interests.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Good News For The Budget, For Now

The year is ending with good news for the city’s budget from two public officials. Mayor Michael Bloomberg is reporting both new revenue and new savings, and thus a projected deficit much lower than originally expected. City Comptroller William Thompson offers a generally encouraging view of the city’s economy in his annual financial report. The comptroller’s report also offers a useful review of the ways in which Bloomberg crafted balanced budgets despite daunting challenges.

But the report also hints at some of the management problems facing Bloomberg’s second term.

BLOOMBERG’S BUDGET, AS OF NOW

Bloomberg’s recent budget modification of the 2006 city budget promises a budget surplus for this year of at least $1.7 billion. The surplus is largely the result of nearly $2 billion of additional tax revenues, based primarily on the continuing boom in housing-market transactions. On the expense side, there are some $450 million of new Medicaid savings.

Add this projected surplus to additional tax revenues expected for 2007, and what once threatened to be a $4.2 billion deficit in 2007 is now looking to be $2.3 billion. This is still a lot of money to be in the hole, of course, but it is quite an improvement in less than five months.

But the good news in revenues obscured, at least temporarily, a big change in expenses for the future. Union contract settlements have added $661 million of labor costs to this year’s personnel budget and $1.1 billion to the 2007 budget.

THE AUDITOR VIEWS THE CITY’S PERFORMANCE

The comptroller’s comprehensive annual financial report, required by the city charter, offers a necessary independent view of both the city budget and an assessment of the city’s management performance.

The report notes that the 2005 budget marked the 25th year of balanced budgets for the city, an impressive rebound after the fiscal problems of the 1970s. The economy has improved, with the city’s gross city product increasing by 3.3 percent in fiscal 2005, after three years of decline. The unemployment rate dropped from 7.9 percent in 2004 to 6.1 percent in 2005. Moreover, the comptroller suggests that the city’s economy is healthier than the nation’s.

But the report makes clear that many problems remain in city agencies. The comptroller has, for instance, challenged the documentation and “fiscal clarity” of education department policy and practices. He suggests that budget reporting in the department has “not kept pace with [its] structural changes.”

In his role as city contract administrator, the comptroller found that the department of homeless services had “falsified an annual inspection report” on a 800-bed homeless facility in upstate New York. Sanitation department contracts were rescinded because of altered scoring sheets during the contract-selection process.

Contracts – 15 Percent Of The Total Budget

The report underscores the importance of city contracting. Contracted services (not including capital budget contracts) totaled $7.84 billion in 2005, nearly 15 percent of the total city budget. The dollar value of contracts was up six percent from the previous year. The biggest contract areas include $690 million for school transportation, $895 million for non-public school handicapped children services, and $625 million for mental hygiene services. The scope of these privatized, publicly funded services may deserve much closer mayoral and legislative oversight.

Yankee Deadbeats

In another role, the comptroller’s 81 audits and special reports provided further oversight of mayoral agencies. The comptroller found – not for the first time – that the New York Yankees, who lease the stadium from the city, shortchanged the city. They underreported over $9 million in revenues and overstated deductions against revenues by $34.5 million. The Yankees, who stand to receive hundreds of millions of dollars in future city and state subsidies for a new stadium, owed (and subsequently paid) an additional $3.6 million in fees.

Problems In Human Resources, Finance, Fire, Etc

The audit unit also found problems in the human resources administration (questionable vendor payments), the department of finance (weaknesses in the administration of the commercial incentive and abatement programs), and the fire department (inadequate controls over EMS ambulance transport fees). Audits also revealed major problems in implementing information technology at HRA and the department of city administrative services.

Budget Up 31 Percent, Taxes Up 33 Percent

One of the most useful sections of the comptroller’s report is a series of 10-year statistical tables. Those tables are a handy way to see what happened during the first Bloomberg term. Comparing fiscal years 2001 and 2005 (which ended June 30, 2001 and 2005, respectively), for example (not adjusting for inflation):

· The city budget grew 31 percent, from $40.2 billion to $52.8 billion.

· City taxes were up 33 percent, from $23.2 billion to $30.9 billion.

· City real property taxes rose 41 percent, from $8.2 billion to $11.6 billion.

· Property-transaction taxes grew 161 percent, from $900 million to $2.3 billion.

· The personal income tax was up nearly 16 percent

· The sales tax, 19 percent

· Business income taxes, up 27 percent.

The mayor’s $1.50 per pack increase on cigarettes (split with the state) jumped receipts by over 350 percent, from $28 million to $127 million.

IBloomberg’s18.5 percent property tax rate increase and the explosion in property transactions (resulting in the huge property-transfer and mortgage-recording tax gains) have been key to the 31 percent increase in the city budget. The mayor’s November modification says that those property tax transactions continue at an unexpectedly high level.

During the same four years, the size of the city workforce increased by nearly six percent, from 249,824 to 264,061.

And Non-Mayoral Parts Of City Government

Given the expansive nature of budget-building over the past four years, there is a touch of irony in the fact that the comptroller’s own budget has declined during that period by over 2.5 percent, to $51.3 million.

The other citywide office, the public advocate, which had a tiny budget to begin with, did see a 17 percent increase in its budget, to $3.1 million.

The borough presidents, who lost most of their budget and land use powers with the elimination of the Board of Estimate in 1989, have also seen their offices cut back dramatically. The combined offices lost 26 percent of their budgets from 2001 to 2005, dropping to $23.1 million.

The city council, which determines its own budget under the charter, has been very conservative in budget terms. Its budget increased only 4.4 percent from 2001 to 2005, from $44.4 million to $46.3 million.

Perhaps there is a case to be made that in a city so dominated by the structural powers of its mayors that the city’s countervailing institutions – the comptroller and city council in particular – should be given more resources.

The Mayor’s Optimistic Number

The mayor’s budget numbers are optimistic. But let’s not forget that, very soon, the city and state comptrollers, the state Financial Control Board, and the Independent Budget Office will all be weighing in with their own analyses of the mayor’s optimistic forecasts.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Tax Reform In Bloomberg's Second Term?

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg said in his victory speech that he believed his re-election sent a message “that you can make the tough decisions and be re-elected, as long as they are the right decisions," it seems clear what tough/right decisions he was talking about. At the top of the list has to be his tax hikes.

The boldest move of his first term was proposing and selling a $3 billion tax package, the key to resolving a $6 billion budget deficit. The package was a burden for most New Yorkers, but the public seems to have accepted his argument that this is an expensive city, and taxes are basic to essential services.

That is why there is hope among fiscal experts of both liberal and conservative perspectives that Bloomberg will devote his second term to reforming the city’s tax system, particularly its incomprehensible property tax, its roller-coaster personal income tax rates, and its mostly hidden corporate tax breaks.

In New York’s think-tank world, the conservative Manhattan Institute’s E. J. McMahon’s new study, “Pricing the â€Luxury Product’: NYC Taxes Under Mayor Bloomberg,” urges restraint on city personal income tax rates and calls for a city/state commission to reform the city’s property tax system.

The progressive Fiscal Policy Institute’s James Parrott, in a new study, “Hudson Yards Tax Breaks, Unwarranted and Fiscally Irresponsible,” analyzes an acceleration of corporate tax abatement and argues against long-term tax breaks for West Side developers. (Juan Gonzalez provided a short review of the study in the Daily News.)

The Property Tax

E. J. McMahon believes reform should begin with, if not end with, the city’ s property tax system, which produces nearly 40 percent of all city tax revenues. At a Baruch College School of Public Affairs seminar on the property tax held October 31, Independent Budget Office Deputy Director George Sweeting released new data that underscore the inequities and what McMahon calls the “Byzantine” complexities of the current system.

The current problems began with 1981 state legislation that set up the current system, which essentially protects city homeowners. But one kind of owner (1-, 2- and 3-family house owners) has a lower burden than most coop and condo owners. Commercial owners have a much higher burden, and renters, who pay a substantial share of their landlords’ property tax in their rent, have almost as high a burden as commercial owners.

So, for example, according to the new data from the Independent Budget Office, on a piece of property worth $300,000 – if the property is a one-family house, the typical 2005 property taxes would be $1,602; if it’s a co-op, the typical property taxes would be $2,772; but if it's a rental property, even though it's worth exactly the same amount as the private home or the coop, the typical property taxes would be nearly eight or five times higher, $13,050.

These inequities are, in large part, created by a bizarre assessment process. In most localities, a property assessment is based on a property’s market value, and the tax bill is determined by simply multiplying that assessment by the current tax rate. Not in New York City.

Here assessments are only a fraction of market value. Assessments of houses, for instance, are targeted at six percent of market value. Thus a $300,000 house would be assessed at $18,000. Assessments of commercial and rental apartment buildings, on the other hand, are set at 45 percent of market value. A building with a $10 million market value would have an assessment of $4.5 million. Co-ops and condos are assessed as if they were rental apartment buildings, creating even more confusion.

To further protect homeowners, there are caps on annual assessments -- no more than six percent for house owners in one year, or 20 percent over five years. There are slightly higher caps for co-op and condo owners.

Recent data from the city’s finance department show the effects. A house with a market value of $350,000 saw its market value rise by 76 percent from fiscal year 2001 to 2006, but the assessed value rose by only 20 percent. The effect of the residential caps is that much of the increase in market value in owner-units is never “captured” in the assessment, thus reducing owner tax bills over the long run as well as short run.

The McMahon report says, “While all cities have real property taxes, few if any could rival the complexity, inequity, and opacity of New York’s system.”

Absent the overall reform that McMahon urges, attempts to fix property tax inequities have only created new problems. For instance, in order to lower the burdens of coop and condo owners, the mayor and city council in 1997 introduced a property tax abatement for them (since extended to 2008). The abatement ranges from 17.5 to 25 percent of the property tax bill.

The new Independent Budget Office data show that because of the convoluted assessment practices, over 78,000 co-op and condo units actually had lower tax burdens than the typical house owner before the abatement. And the abatement has moved several thousand more units into this privileged house owner tax status. In dollar terms, it means that nearly $100 million of the annual abatement is a “waste,” because it goes beyond the original equalizing goal.

Personal Income Tax

The second most important city tax – now representing about 22 percent of city tax revenues – is the personal income tax.

Looking to Bloomberg’s second term, McMahon and the Manhattan Institute fear an extension of the city’s temporary top personal income tax rates for the city’s highest earners (over $150,000), which under current law expire December 31, 2005. They fear many of the city’s millionaires will flee the city to avoid the 4.45 percent top tax rate – which if extended beyond the end of this year would bring in approximately $500 million.

But a similar top 4.45 percent personal income tax rate was in effect through most of the 1990s, after being introduced by former Mayor David Dinkins and Council Speaker Peter Vallone during a recession and fiscal crisis in 1990. The fear of high-end earners flight seems exaggerated, since that rate apparently had no negative impact on the booming city economy of the late 1990s, and in fact, helped create huge Rudy Giuliani budget surpluses.

A city tax commission could take a look at the roller-coaster changes in personal income tax rates over the last 15 years and test McMahon’s dubious claim that the early 1990s tax increases triggered the loss of 300,000 jobs in the city. As McMahon suggests, personal income tax revenues can be volatile because of economic ups and downs, but that does not mean the rates can’t be set efficiently and progressively.

Commercial Tax Breaks

James Parrott’s study of commercial tax breaks – which mayoral administrations sell as “economic development” -- is revealing: In the four years after 2000, these increased over 72 percent, from $334 million to over $575 million. Parrott argues for a review of the rationales for these breaks, many of which were arguably unnecessary, especially in Manhattan; the developments would have gone ahead without deep city subsidies.

Parrott also pulls the curtain on what’s happening in Manhattan’s West Side (Hudson Yards) development area. The city’s financing of the infrastructure that will support this development – the extension of the #7 subway line is the biggest piece – is not yet completely clear. The mayor and the city council agreed last winter to use city funds for the start-up of the financing, but long-term financing is based on using new property tax revenues generated from the development area.

The problem is that the mayor wants to use a pre-determined PILOT – a payment-in-lieu-of-taxes – for the whole development period. A PILOT is usually determined by a negotiation on a specific property between the city and a developer that sets a less-than-full-property tax payment. (The Port Authority, for instance, paid the city a PILOT for the World Trade Center that was about 25 percent of what it would have been had the property been fully taxed.)

But here, the city proposes, through its obscure Industrial Development Agency, to establish what is called a Hudson Yards Uniform Tax Exemption Policy that Parrott says “will likely permanently institutionalize the granting of across-the-board tax breaks for any commercial development in New York City.” The immediate Hudson Yards effect would be to grant a “uniform” break for all Yards developers through at least the year 2040.

Public economic development investments provide incentives for private development. Why assume decades in advance that further incentives will be needed at all, let alone at some arbitrary and uniform tax-cut level set in 2005? Parrott argues that what “gets locked in with this ill-advised economic policy are the inequities that result when large companies receive sizable property and other tax breaks that shift the city’s tax burden to smaller businesses and other taxpayers.”

The Industrial Development Agency will, according to Good Jobs New York (a joint venture of the Fiscal Policy Institute and Good Jobs First which monitors the secretive processes of New York’s public authorities), in the near future hold a hearing to determine just what this important uniform exemption will be. Will it be a 50 percent discount? A 20 percent discount? The long-term costs – through lost property tax revenues – could be in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Another obscure public authority – the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation – is the financing mechanism that controls the borrowing that will pay for the Hudson Yards infrastructure. It has a mayoral-dominated six-member board: the city comptroller, the speaker of the city council, three mayoral appointees, and one independent member, appointed by the mayor. They will have to approve any financial plan.

A City Tax Commission?

Before the city goes ahead with this dubious financing mechanism, there ought to be a serious public review of its long-term economic, revenue, and equity consequences. A city tax commission would be the perfect vehicle.

A city tax commission could take the long, comprehensive view. It could examine the overall impact of all revenue policies and recommend changes that would -- among other goals -- make the property tax fairer, simpler, and more efficient; stabilize and make more progressive the personal income tax; and analyze the revenue as well as economic impact of current economic development policy.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.

Â

Mayor's Management Report for 2005: Thinner, Less Useful

Michael Bloomberg released his mayor’s management report for fiscal year 2005 on September 12, one day before the Democratic primary election, a preemptive strike against his political opponents. Fair enough: The report is required by the city charter in order to give voters a useful measure of mayoral accountability.

In this latest report, the mayor says that his administration has achieved “high levels of service delivery [and] in some cases, historic progress.”

But much like last year’s report, this one gives voters little help. It includes too many insignificant indicators, lacks any overview or sense of priorities, and says little or nothing about such major (and problematic) policies as the reorganization of city schools, big changes in homeless services, the costs of school construction, and high levels of overtime among the city’s uniformed services.

And a number of recent surveys and independent management studies challenge the mayor’s rosy assessment, identifying some real problems and providing an alternative view of mayoral accountability.

SMALLER, BUT BETTER?

The printed version of the 2005 Mayor’s Management Report is much smaller than the ones put out during the administration of former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani (276 pages in 2005, compared to 1,162 pages in 2001). Many observers admire this change, including most participants at an expert panel sponsored by the mayor’s charter revision commission on April 4. But one dissenter on that panel, deputy city comptroller Greg Brooks, pointed out that smaller is not necessarily better.

Brooks noted a net reduction of 1,087 indicators (from 2,606 in 2002 to 1,519 in 2004), a 42 percent cut. He also noted that 16 percent of the 1,519 remaining indicators are related to 311, creating what he characterized as a “soft indicator of the quality of city services [that] could in fact skew results.”

The good news is that the mayor’s management report does have a number of useful statistics, if not many performance indicators. It provides glimpses of current city demographics and some social conditions. The basic problem is that the report does not connect the dots between those facts and city policy.

Some of the more glaring examples include:

- Graduation Rates

- Between 2001 and 2004, the percentage of students graduating from high school within four years increased, from 51.0 to 54.3 percent.

- But in the same period, the percentage of students graduating from high school within seven years declined, from 69.5 percent to 68.0 percent.

Issue to connect the dots: What improves/impedes graduation rates?

- Special Education

- From 2001 to 2005, NYC student enrollment has decreased by nearly 30,000, to 1,075,300.

- But in the same period, the number of special education students has increased by 5.5 percent, from 167,800 to 177,100.

Issue to connect the dots: Is a higher percentage of students in special education good or bad?

- Homeless Families

- Between 2001 and 2005, the average number of homeless families in shelters per day has increased by 55 percent, to 8,623 (including 14,849 children).

- In the same period, in spite of a focus on “prevention,” there’s been a 46 percent increase in families entering the shelter system for the first time (6,618 in 2005).

Issue to connect the dots: What’s the actual impact of prevention work?

- Crime

- Since 2001, major felony crimes have decreased by 21 percent (murders by 15 percent, rapes by 11 percent), from 172,646 to 136,491.

- But the number of uniformed officers has decreased in the past four years by 3,141, or eight percent.

- And in the same period, police overtime has increased by 20 percent, from $338 million to $406 million.

- And over four years civilian complaints against police officers increased by 46 percent, to 6,358 in 2005.

Issue to connect the dots: Are officer levels, overtime, crime statistics, and civilian complaints related?

THE VIEW OUTSIDE CITY HALL

What The Customers/Constituents Say On Education

One performance indicator that would improve the mayor’s management report in many agencies is the constituent/customer survey. In June the city council’s education committee published an education oversight report card, based on a survey of 689 parents and 30 teachers. Using a state-based grading system (1=Not Proficient, 2=Basic, 3=Proficient, 4=Advanced):

- Three of 14 categories – class size, teacher and principal morale, special education, and operations -- got the lowest score of 1.

- High school admissions got a 3, and competition and choice a 4.

- All other categories (including instruction, communication, and parent involvement) received 2’s.

The Quinnipiac University September 22 poll of 1,504 NYC registered voters reported mixed public judgments of school performance: Some 66 percent of voters are dissatisfied with the public schools (an improvement from earlier polls over the past three years that showed dissatisfaction ranging as high as 78 percent). But the mayor got a 52 /33 percent approval/disapproval rating for his public education role, and chancellor Joel Klein a 40/33 percent rating.

Overall, 12 percent of voters were “very satisfied” with the ways things are going in the city, with 51 percent “somewhat satisfied,” 22 percent “somewhat dissatisfied,” and 13 percent “very dissatisfied.”

What The Independent Monitors Say

The city comptroller’s office and the NYC Independent Budget Office, like the the city council, serve as alternative governmental sources of accountability measures, particularly in data and technology areas. For instance, the comptroller’s May 2 audit of "the paperless office system" of the Human Resources Administration showed that a system that has cost $47 million and was (according to the 1996 Mayor’s Management Report) to be completed by April 1998, has yet to be finished.

Furthermore, HRA did not provide complete documentation of the many contracts associated with this project, and gave “the false impression” that the paperless office system “was progressing smoothly.”

The Independent Budget Office’s September fiscal brief, "Follow the Money: Were School Construction Dollars Spent as Planned?” (in pdf format) identified major problems with reporting systems: “Determining how successful the education department was in implementing its $6.9 billion 2000-2004 capital plan was a difficult task, plagued by inconsistent and missing data….The lack of detail linking the spending to individual projects limits the comparison between plan and actual.” (This is just what the mayor’s management reports are supposed to do, but don’t.)

In spite of the data restrictions, the IBO doggedly pursued a projected vs. actual cost study of a small part of the total capital plan -- 14 new elementary and four new high schools. The study found that actual spending was 22.0 percent and 38.1 percent higher per square foot in the elementary and high schools, respectively, than projected in the original plan. (The study suggests those percentages may be understated.)

SPECIAL EXAMPLE: SPECIAL EDUCATION

For decades 110 Livingston Street, the city Board of Education’s central office in Brooklyn, was a notorious symbol of the modern bureaucracy – distant, unresponsive, ineffective. Mayor Bloomberg, newly in charge of public education and sensitive to the symbol, moved central headquarters to the Giuliani-renovated Tweed building, next door to City Hall (although the $100 million cost of its renovations and the building’s association with the city’s most famous crook raised some eyebrows).

But has the mayor simply created a different monster? A new management study of Bloomberg ’s reorganization of special education describes an eerily familiar structure -– “a bureaucratically-driven” agency that has continued bad old policies and created a new set of dubious policies and procedures. Written in a polite and technical academic style, the study lays out an astonishing range of management problems, from complex and confusing infrastructure and ineffective data systems to a central-office reliance on an old “medical model of treatment” that the researchers say contradicts current best practices.

“Comprehensive Management Review and Evaluation of Special Education” was written by a team of seven researchers, headed by Thomas Hehir, a lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Contracted by the city’s department of education, its purpose was “to critically assess the recent reorganization of…special education evaluation and placement processes and special education oversight in light of the Jose P. litigation.”

The study is independent of both the department and the plaintiffs in that litigation, which has been in place since 1979, when the city was found in violation of the federal Education for All Handicapped Children Act (now the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004).

The report is also the first significant study of the core element of the mayor’s overall reform of education -– a highly centralized operation that has created 10 regions out of 32 community school districts and re-structured special education in those 10 regions.

The study says, in sum, no, the department does not yet have an effective management structure. Of 14 findings, nine are negative. Five positive findings applaud the commitment of the agency’s many teachers and specialists to their work. But six of the nine negative findings show structural and management problems:

- “The complex …infrastructure…leads to confusion with respect to roles and responsibilities and does not provide sufficient support to principals and school staff.”

- “The management of special education…is not sufficiently data-driven.”

- Policies and procedures “are not being communicated to personnel in an effective manner.”

- Pre-referral measures “are implemented inconsistently and are often duplicative.”

- “[A]n effective [due process] system is still not in place.”

- Staff development efforts “are insufficient.”

The other negative findings are more conceptual in nature. The authors question the special education medical model that the mayor and chancellor have inherited but also seem to have adopted. The report argues that the model leads to “treatments” by specialists and therefore unnecessary segregation of services. They suggest shifting to a more comprehensive, integrated, and local set of services.

The 2005 Mayor’s Management Report says nothing about these significant management and policy questions (special education in the 2003-2004 school year represented nearly 25 percent of the education budget, or $3.4 billion). The department press release accompanying the study quotes only its statement that the department is “moving NYC in the right direction.” It ignores the specific litany of structural/ management problems.

The mayor’s recent charter revision commission considered (and ultimately tabled) a mayoral initiative to reduce the number of reports. The thinness of the current mayor’s management report indicates that the problem is not too many reports. The problem is too few that are useful.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

The Fiscal Crisis After 30 Years

It was a dramatic time, Felix Rohatyn recalled: “Almost daily crises … heroes and villains; us against them." In short, he said, it was “the most rewarding experience of my professional life."

Few people would sound so nostalgic about the fiscal crisis of 1975, a time that saw massive layoffs, piles of garbage in the street because of cutbacks in the Sanitation Department, and a dangerous decrease in police patrols. But of all the experiences in his long life, Rohatyn takes the most satisfaction from his role in saving New York City from bankruptcy.

At the time, the federal government accused the city of handling its money like a heroin addict, focusing only on its next fix -- relying on deceptive accounting, borrowing excessively, and refusing to plan. This led banks to stop lending the city money.

|

Ballot Questions Question 1 -- Amending the state budget process. |

Now, 30 years later, says Rohatyn, the city’s good financial management is taken for granted. It has honestly balanced its budget for over 25 years, and has rebuilt trust among the banks that refused to lend it money in the 1970s. The Financial Control Board -- a state-ordered budget watchdog that Rohatyn helped form -- is given much of the credit for this turnaround.

But with the law that created the Financial Control Board set to expire in 2008, Rohatyn and others are concerned that the city may relapse.

This November, New Yorkers will vote on whether to put some of the practices that the Financial Control Board requires into the city charter. Most budget experts agree that these requirements are good ones. But some worry that without an external monitor New York City will slide back into the habits that caused it so much trouble in the past.

To see what happens when no discipline is imposed on budget makers, many point to New York State. Albany now regularly engages in the kinds of behaviors that the Financial Control Board has weaned the city from.

The state’s budget is also the subject of a referendum this November. If passed, it will change the roles of the governor and the legislature during budget negotiations. This proposal will not directly address financial mismanagement, but its advocates hope that by increasing accountability and transparency, the new budget process will force state officials away from their worst budgetary tendencies. Opponents of the measure, though, say that the amendment will only make such problems worse.

THE 1975 FISCAL CRISIS

New Yorkers continue to debate what drove the city to the brink of bankruptcy in 1975.

Some argue that New York City’s liberal officials borrowed money freely to spend on social programs, while powerful municipal unions forced them to agree to obscenely generous contracts. Others say that a variety of outside factors were a driving factor -- the city was increasingly tied into a world economy that was in shock from the 1973 Arab oil embargo; it was victimized by the banks upon which it relied to buy bonds; the federal government left the city in the lurch.

Some argue that New York City’s liberal officials borrowed money freely to spend on social programs, while powerful municipal unions forced them to agree to obscenely generous contracts. Others say that a variety of outside factors were a driving factor -- the city was increasingly tied into a world economy that was in shock from the 1973 Arab oil embargo; it was victimized by the banks upon which it relied to buy bonds; the federal government left the city in the lurch.

Rohatyn saw enough blame to go around (in pdf format):

"The banks had lent too much and checked too little; the unions took more than the city could afford; the city cooked the books, and borrowed; and the state encouraged this whole exercise," he said.

Whether or not they were the root cause of the crisis, New York City’s financial practices were out of control at that time, say experts. The city was relying excessively on debt; by Rohatyn’s account its short-term debt had risen from about zero in 1970 to $6 billion in 1975. The city relied increasingly on budgetary tricks to balance the budget –- reclassifying operating expenses as capital investments; continuously pushing expenditures onto the following year’s budget; or simply not keeping good enough records to know what was really going on.

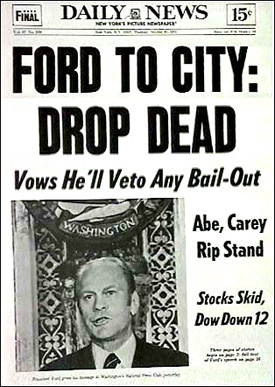

Ken Auletta writes in his book The Streets Were Paved With Gold –- one of numerous books written on the topic -– that the city acted as if it wasn’t bleeding to death when in fact it was hemorrhaging severely. But when first the banks, and then the federal government, declined to bail the city out (the latter prompting one of the most famous tabloid headlines in New York history: FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD), it became apparent that something needed to be done.

The answer, in Auletta’s words, was “fiscal martial law.”

THE FINANCIAL CONTROL BOARD

To get the city's fiscal matters in order and convince investors to resume the purchase of the city's bonds, New York State established the New York City Emergency Financial Control Board. The board was comprised of the mayor, the governor, the city and state comptrollers, and three private industry experts. It held veto power over the city’s budget.

The board required the city to adopt accepted accounting practices, to end the most egregious budgetary sleights of hand, and to work towards the type of fiscal responsibility that would convince banks to trust New York. The city was able to avoid declaring bankruptcy, and in 1982, banks resumed buying short and long term municipal bonds.

The board’s veto power over the city budget -– the so-called control period -- ended in 1986. Since then, the board has served a monitoring role, with the ability to resume its active role if the city’s budget deficit exceeded $100 million at the end of a fiscal year.

So far, the city has successfully avoided such action.

"The city of New York today, I believe, is probably the best governed in terms of finances," said state comptroller Alan Hevesi. "Our reporting systems, our financial transparency, are probably the best in the country. And that's because of this law [that created the Financial Control Board]."

The board has had several lasting effects on the way the city's budget process works:

Making the Governor a Partner: One of the primary reasons for establishing the financial control board was to force the governor and the mayor to be partners in making sure the city is healthy financially. Because the governor sits on the board, he is directly responsible for the city’s performance. The board also provides the state with a permanent structure for keeping abreast of the city’s finances without creating the tension that can arise from state investigations of specific city practices.

Political Cover: Something that became clear during the 1975 fiscal crisis was that good financial and budgetary practices sometimes run counter to good politics. City officials have an incentive to put off difficult decisions. By forcing officials to make these decisions, the board becomes a willing scapegoat.

"Whatever those decisions are -- taxes, service cuts -- they are going to be unpopular to some sector of the city," said Jeffrey Summer, executive director of the board. "And if we take the blame for it, that's fine, so long as the city does it."

A Culture of Accountability: The board’s most widely cited accomplishment has been to give an air of credibility to the city's budget numbers. New York City's accounting, which has been suspect in the past, is now trustworthy. Because the board requires the city to have a four-year financial plan, officials must also address future consequences of their actions. Good financial management, said Rohatyn, has become “part of the city’s DNA.”

There is a general acknowledgement there is a culture of discipline among city officials that has not existed in the past. Still, some remain skeptical about the durability of this shift.

"There has been a vast change in what people think they can get away with," said E.J. McMahon of the Manhattan Institute. "But has the culture really profoundly changed? No."

THE END OF THE BOARD?

The control board is scheduled to exist until 2033. But in 2008 it will lose its $3 million in annual funding and its ability to impose a control period over the city.

Some think that the board should be allowed to expire, arguing that the city has earned its independence through its performance since the 1975 fiscal crisis. They argue that the city and state comptrollers, the Independent Budget Office, the Citizens Budget Commission are monitoring the city closely enough to make sure it doesn’t backslide -- despite the fact that all of these organizations except the Independent Budget Office existed before the fiscal crisis.

"I think that [the board] has handled itself very well, and I think that when it expires it did a good job and left a legacy, but there's no reason for it to be in business," said former mayor Ed Koch.

Not everyone agrees. Because the board has the option to impose a control period, it alone has the power to force the city to act responsibly. Taking this away, some say, is dangerous.

"This is like talking about allowing just a little sip of table wine in the house of a raging alcoholic who once almost killed himself," said McMahon.

McMahon argues for a “permanent, semi-mothballed” board that can step in if the city performs badly. Both the state and city comptrollers also say that the law that created the board should be extended in some form. (The board itself has no stance on whether it should continue to exist.)

BALLOT QUESTION 4: PROPOSED REVISION TO THE CITY CHARTER

Seemingly in preparation for the board’s expiration, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has proposed revisions to the city’s charter that voters will decide on in November (in .pdf format). These revisions would require the city to balance its budget using generally accepted accounting standards, create a four-year financial plan, and limit the use of short-term debt – all things the board currently requires.

This would give the city added independence while guaranteeing continued financial responsibility, argue proponents: “As there always has been the sense that the city should have more autonomy in self-government, this proposal would create the ability for the city to monitor itself regarding financial matters,” wrote the Women’s City Club of New York in a statement.

Frank Mauro of the Fiscal Policy Institute, however, argues that the provisions become ineffective when there is no one outside the administration specifically assigned to make sure that the city upholds its responsibilities.

Still, other fans of the board don’t necessarily object to the city charter revisions. Deputy City Comptroller Marcia van Wagner says that the revisions encourage good behavior and should be supported; they should just not be used as justification for eliminating the board itself.

“There's no harm in [the revisions],” she said. “But I think what people feel is that there needs to be some kind of discipline that is imposed externally."

NEW YORK STATE’S FISCAL MISMANAGEMENT

In contrast to New York City, New York’s state government has not been forced to answer to an outside entity. The results, say budget experts, have clearly been destructive.

“I think the behavior of the city and the state, in terms of how they run their budget process, has diverged tremendously to where the city now adheres to very high standards, and the state is not adhering to the low standards it has,” said Diana Fortuna of the Citizens Budget Commission.

Among the behaviors cited as particularly dangerous are:

Borrowing for Operating Expenses: While the city has limits on short-term debt, Albany borrows to pay its operating expenses. State comptroller Alan Hevesi refers to this as the “cardinal sin” of finance, and others have likened it to taking out a mortgage to pay for groceries.

Unbalanced Budgets: Unlike city officials, state budget makers are not required to balance the budget according to general accounting principles. Albany regularly runs large deficits.

Outstanding Debt: The state doesn’t have the debt limits imposed on the city, and total outstanding debt in the state is $48 billion. As a result, credit rating agencies give low marks to New York State’s bonds, making borrowing more expensive.

Abuse of Public Authorities: The state borrows large sums of money through the public authorities, removing this money from the budget process completely. Public authorities, funded by the state but outside of the control of voters, have increased their debt by almost seven-fold over 20 years. The 18 largest authorities now have about $120 billion in outstanding debt.

These practices are symptoms of a culture that discourages good fiscal practices in the name of political expediency, says Fortuna. They affect not only the fiscal health of the state itself, but also local governments that are forced to assume greater responsibilities as Albany increasingly shifts the burden for expensive programs onto them.

The state’s dysfunction has become the subject of much attention in the past year. Good government groups, the press, and lawmakers themselves have called for changes in the way the state’s affairs are run. These reforms have not only dealt with the budget process – everything from the non-competitive nature of elections to how committees work to the way lawmakers vote on bills has come under criticism. But with a string of late budgets 20 years long (broken this year), the budget process ranked high on the list of issues to confront.

BALLOT QUESTION 1: PROPOSED STATE BUDGET ADMENDMENT

To address problems in the state’s budget process, legislators and some good government groups are backing an amendment to the state constitution, which will be put to voters this November. While this does not directly require anything specific in terms of financial management, its proponents hope that it will encourage more responsible practices through transparency and accountability.

The main provision transfers power over the budget from the governor to the legislature. Currently, the governor creates an executive budget that lawmakers have limited powers to change. Under the proposed amendment, if no agreement is reached on the budget by the beginning of the fiscal year, then a contingency budget based on the previous year’s budget would go into effect. This would automatically become the basis for the new budget, and the legislature would have more power to amend it. Other provisions would establish an independent budget office whose members are picked by the legislature, and make expenditures that are currently not part of the regular budget part of general budget negotiations.

Supporters of this proposal (in .pdf format), which include good government groups Common Cause and the New York Public Interest Research Group as well as many legislators, say that this amendment will give the public more information about what officials are doing, making them more accountable. It will also bring the balance of power between the governor and the legislature more in line with that of other states, they say, and make sure the budget is on time. The overall effects, they say, will be modest, but will lay the foundation for future reforms.

Critics of the amendment believe the effect will be more profound (download video clip). Among the opponents of the proposal is Citizens Union, (whose sister organization, Citizens Union Foundation publishes Gotham Gazette), the Citizens Budget Commission, the Manhattan Institute, and the Business Council of New York State.

Instead of guaranteeing an early budget, they say, the amendment gives lawmakers a reason not to negotiate with the governor until after the budget deadline, at which point they will have much more power. Had lawmakers been given such power in 1975, some say, upstate legislators would have kept Governor Carey from funding the Financial Emergency Act. Today, they say, this increased power will encourage lawmakers to spend money freely.

While they question the reform’s potential to make a positive impact, critics of the amendment do not question the need for change itself. Almost no one believes the state is handling its financial affairs sensibly.

“Change is very, very badly needed,” said Fortuna.

THE FISCAL CRISIS OF THE 1970s AND THE FINANCIAL CONTROL BOARD

- The Fall and Rise of New York by Felix Rohatyn

- The Coming Emergency and What Can be Done About It by Felix Rohatyn

- A Coalition from City, State, National Levels is Needed to Help new York Overcome its Fiscal, Social Crisis by Felix Rohatyn (video clip)

- Gotham’s Fiscal Crisis: Lessons Unlearned by Fred Siegel and EJ McMahon

BALLOT PROPOSAL FOUR: PROPOSED CITY CHARTER REVISION

NEW YORK STATE’S DYSFUNCTIONAL GOVERNMENT

- Albany’s Dysfunction by Gotham Gazette

- New York State’s Fiscal Condition by State Comptroller Alan Hevesi (in .pdf format)

- The New York State Legislative Process: An Evaluation and Blueprint for Reform by the Brennan Center

BALLOT PROPOSAL ONE: PROPOSED AMENDMENT TO STATE CONSTITUTION

- Text of Ballot Proposal One

- Overview by the Rockefeller Institute

- Vote YES on Budget Reform: The November 2005 Budget Reform Announcement by Common Cause/League of Women Voters/New York Public Interest Research Group(in .pdf format)

- The Runaway Spending Amendment by the Business Council of New York State

- Breaking the Budget in New York State: What’s at Stake in November’s Referendum by Manhattan Institute (video clip)

Mayoral Issue Grid: Finance

FINANCE

New York City’s annual budget will pose a problem for the next mayor. Experts project that the city will face a $4.5 billion deficit in each of the next two years. If the mayor cannot reduce spending, he or she will be forced to raise taxes or generate revenue from fees, fines, or tickets. The property tax is the only tax the mayor and City Council can raise without the approval of the State Legislature.

To reduce the city’s projected budget deficit, Fernando Ferrer says that he will eliminate loopholes in the tax code that he says costs the city $2 billion a year. He also promises to fight for more funding from Albany, particularly Medicaid payments. Ferrer also believes that the commuter tax should be reinstated, which would require the approval of the State Legislature.

While Ferrer says he will not raise taxes to balance the budget, he has proposed a stock transfer tax to help raise $1 billion for education.

Ferrer outlined a property tax rebate plan that would "offer a $100,000 property tax exemption to the approximately 600,000 New York homeowners of coops, condominiums and 1, 2, and 3-family homes valued under $800,000. Every qualified homeowner whose home is valued at $100,000 or more would automatically enjoy $973 in savings. Meanwhile, homeowners with homes valued above $800,000 would continue to receive the $400 rebate."

Renters would also receive relief. Under the HOPE plan, Ferrer would provide "an average annual benefit of $295 to renters living in rent-regulated units who have a household income below $60,000 and at least one child under the age of 18."

Michael Bloomberg says that the city’s budget can be divided into two parts: the spending that the city controls and the spending mandated by the state.

Bloomberg argues he has taken steps to reduce the budget where he can, cutting $4 billion from the budget and reducing the city’s workforce by 15,000 employees.

The city’s projected deficits, he says, are a result of things out of the city’s control, like Medicaid and pensions. He supports Medicaid reform and worked to reduce pension costs.

Although he raised taxes in the past, Bloomberg opposes increases in the income taxes or a tax on Wall Street stock transfers.

RELATED ARTICLES:

- 10 Budget Choices Facing The Next Mayor

- The Mayoral Candidates on Budgets, Taxes and Spending (Forum)

- $50 Billion Budget -- A Shortsighted Use Of Surpluses

- Budget Transparency After The West Side StadiumÂ

Mayoral Issue Grid: Jobs

JOBS

-Top Priority

Although the city’s economy has recovered since the months after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, an estimated 230,000 New Yorkers are unemployed. African-American and Latino males have a particularly difficult time finding a job; 40 percent are unemployed.

The Democratic candidates are focusing most of the attention on small businesses. Small businesses account for 50 percent of all New York City private-sector jobs and generate $4.5 billion in annual city tax revenues.

To help small businesses, Fernando Ferrer proposes a three-month amnesty program to give small businesses the opportunity to pay outstanding fines. He plans to provide real estate assistance, micro-loans, and new programs for women and minority-owned businesses.

He also plans to form a small business advisory council that reports to the mayor, deputy mayor for economic development, and commissioner of the small business department. The panel would make recommendations and proposes policy.

(Read Ferrer’s small business plan)

Michael Bloomberg says he has created 62,000 jobs since July 2003.

He has given tax credits to large corporations like Time Warner, Hearst, the New York Times, and Goldman Sachs to encourage them to build new headquarters in Manhattan.

Bloomberg believes tourism – which is at record levels – is a main engine for job growth.

He has undertaken development projects in Brooklyn, Queens, and Harlem to spur new construction and job growth.

To help small businesses, he opened satellite small business services in each of the five boroughs that offer assistance to owners.

(Read Bloomberg’s job platform)

RELATED ARTICLES:

- Debating Jobs and Economic Development

- In Big Projects, Where Do The Jobs Go?

- Tourism and Jobs

Â

Mayoral Issue Grid: Finance

FINANCE

New York City’s annual budget will pose a problem for the next mayor. Experts project that the city will face a $4.5 billion deficit in each of the next two years. If the mayor cannot reduce spending, he or she will be forced to raise taxes or generate revenue from fees, fines, or tickets. The property tax is the only tax the mayor and City Council can raise without the approval of the State Legislature.

To reduce the city’s projected budget deficit, Fernando Ferrer says that he will eliminate loopholes in the tax code that he says costs the city $2 billion a year. He also promises to fight for more funding from Albany, particularly Medicaid payments. Ferrer also believes that the commuter tax should be reinstated, which would require the approval of the State Legislature.

While Ferrer says he will not raise taxes to balance the budget, he has proposed a stock transfer tax to help raise $1 billion for education.

Ferrer has not outlined any proposed tax cuts.

To reduce the city’s projected deficit, C. Virginia Fields says she will reform the city’s tax code and work toward 100 percent collection of taxes. Fields also believes that the commuter tax should be reinstated, which would require the approval of the State Legislature.

Fields says that “increasing taxes harms our economy” and does not plan to raise taxes to balance the budget.

She opposes an income tax increase and a tax on Wall Street stock transfers.

Fields has not outlined any proposed tax cuts.

To reduce the city’s projected deficit, Gifford Miller says that the mayor must do more to fight for New York City’s “fair share from Washington and Albany.” City taxpayers currently pay $24 billion a year more in taxes than they receive in services from the state and federal government. Miller also proposes a commuter tax of 1.1 percent, which would require the approval of the State Legislature.

While Miller does not want to raise taxes to balance the budget, he has proposed an income tax surcharge on New Yorkers who make more than $500,000 a year to help reduce class size.

He opposes the idea of a tax on Wall Street stock transfers.

Miller has proposed doubling the Earned Income Tax Credit for low income New Yorkers. He also wants to give a renters tax credit to all households that make under $100,000 a year.

To reduce the city’s proposed budget deficit, Anthony Weiner promises to cut $1 to $2 billion a year from the worst-performing city agencies. Weiner also wants to sell government property through an open bidding process, which he says will generate more revenue. He also says he will fight for more aid from Albany and Washington.

Weiner proposes increasing income taxes for those who make more than $1 million a year.

He opposes taxing Wall Street stock transfers.

Weiner has proposed a 10 percent income cut for those making $150,000 or less. (Read Weiner’s tax plans)

Michael Bloomberg says that the city’s budget can be divided into two parts: the spending that the city controls and the spending mandated by the state.

Bloomberg argues he has taken steps to reduce the budget where he can, cutting $4 billion from the budget and reducing the city’s workforce by 15,000 employees.

The city’s projected deficits, he says, are a result of things out of the city’s control, like Medicaid and pensions. He supports Medicaid reform and worked to reduce pension costs.

Although he raised taxes in the past, Bloomberg opposes increases in the income taxes or a tax on Wall Street stock transfers.

RELATED ARTICLES:

- 10 Budget Choices Facing The Next Mayor

- The Mayoral Candidates on Budgets, Taxes and Spending (Forum)

- $50 Billion Budget -- A Shortsighted Use Of Surpluses

- Budget Transparency After The West Side StadiumÂ

Mayoral Issue Grid: Jobs

JOBS

-Top Priority

Although the city’s economy has recovered since the months after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, an estimated 230,000 New Yorkers are unemployed. African-American and Latino males have a particularly difficult time finding a job; 40 percent are unemployed.

The Democratic candidates are focusing most of the attention on small businesses. Small businesses account for 50 percent of all New York City private-sector jobs and generate $4.5 billion in annual city tax revenues.

To help small businesses, Fernando Ferrer proposes a three-month amnesty program to give small businesses the opportunity to pay outstanding fines. He plans to provide real estate assistance, micro-loans, and new programs for women and minority-owned businesses.

He also plans to form a small business advisory council that reports to the mayor, deputy mayor for economic development, and commissioner of the small business department. The panel would make recommendations and proposes policy.

(Read Ferrer’s small business plan)

C. Virginia Fields promises to use the city’s $18.8 billion in annual spending to help small businesses grow. She proposes giving a specific percentage of city contracts to small businesses. She also wants to provide loans and provide training in entrepreneurship.

Fields also wants to grow the biotechnology industry, offering tax incentives for new companies to do research in the city.

Gifford Miller points to his efforts as Speaker of the City Council in creating job training programs, workforce protections, and the “Living Wage” bill, which requires certain city contractors to pay their employees $8.10 an hour, rising to $10.00 per hour by July 2006.

Miller promises to cut taxes for small businesses and expand tax credits for industries in the outer boroughs. He says that the foundations of economic growth are “great neighborhood schools, reliable transportation, and flourishing small businesses.”

Anthony Weiner wants to reduce tickets and fines for small businesses. He also wants to create an ombudsman position at the Department of Business Services to help small business owners.

He would create a $10 million micro-loans program, which gives low interest loans of $100,000 to $200,000 to emerging businesses.

Weiner also promises to increase subsidies for businesses outside of Manhattan. He would require that at least 25 percent of all Economic Development Commission funds be distributed to the boroughs on an equitable basis, by jobs per borough, or population.

He also wants to create a “ShopNYC.com” Web site to help small businesses sell their goods on the Internet.

(Read Weiner’s economic development plan)

Michael Bloomberg says he has created 62,000 jobs since July 2003.

He has given tax credits to large corporations like Time Warner, Hearst, the New York Times, and Goldman Sachs to encourage them to build new headquarters in Manhattan.

Bloomberg believes tourism – which is at record levels – is a main engine for job growth.

He has undertaken development projects in Brooklyn, Queens, and Harlem to spur new construction and job growth.

To help small businesses, he opened satellite small business services in each of the five boroughs that offer assistance to owners.

(Read Bloomberg’s job platform)

RELATED ARTICLES:

- Debating Jobs and Economic Development

- In Big Projects, Where Do The Jobs Go?

- Tourism and Jobs

Â

NY's Ports Booming, But High Costs Of Security Are Eroding Gains

<NYT_BYLINE version="1.0" type=" ">

<NYT_TEXT >

Although the ports of New York and New Jersey have improved their productivity to handle a rising flow of imports, their increased security costs since 9/11 have eroded some of the gains, according to a study released yesterday.

The ports have been booming as they attract a larger share of the goods bound for the Northeast from China and other foreign countries.

But despite huge investments in machinery and computers to improve their efficiency, terminal operators have been hiring at an equally fast pace, according to the report, the first independent study of local port activity since 2001.

The study was commissioned by the New York Shipping Association, whose offices were in the World Trade Center and are now in Iselin, N.J.

The number of jobs at cargo terminals in the ports has increased by more than 29 percent, rising to 20,947 in 2004 from 16,232 in 2000, the report shows.

The volume of cargo flowing through the port increased 27 percent, to 99.9 million tons from 78.6 million tons in 2000.

The growth in productivity in recent years was offset partly by the hiring of additional security guards to screen cargo and workers, the report said.

Frank M. McDonough, president of the association, whose members are shipping companies, terminal operators and stevedores, said they had added about 300 security workers.

The study found that cargo movements through the ports directly supported the equivalent of 122,550 jobs in the region and were indirectly responsible for almost as many jobs in other industries, including wholesale trades, banking and insurance.

The study estimated that the direct and indirect jobs resulted in $12.6 billion in income annually and contributed $5.8 billion in taxes.

It was conducted by researchers at Rutgers University and A. Strauss-Wieder, a consulting firm in Westfield, N.J.

The biggest increases in employment have been in the warehouses and distribution facilities in northern New Jersey, Mr. McDonough said.

Those facilities, way stations for the goods unloaded off ships before they land on store shelves, have added 23,000 jobs since 2000, he said.

Mr. McDonough said the number of stevedores has declined slightly to 2,495, with average salaries of $87,000 a year. About 15 percent are women.

Security has become a big expense since 9/11 as operators like Maher Terminals have had to install radiation portals to check every outgoing cargo container for explosives.

Maher, a family-owned company, is installing a system of gates at its terminal in Elizabeth, N.J., to speed checks on each container and driver entering or leaving the waterfront, said Sam Crane, Maher's vice president for external affairs.

But it will still take at least 35 minutes and, during busy periods, more than an hour, for a truck to drop off an outgoing container and pick up an incoming one, he said.

div>Â