Saving Oakland Lake

Jerry Iannece is a good example of the kind of person who can get things moving in New York City.

"I know how it works," says Iannece, a former district attorney who now serves as chairman of Queens Community Board 11. "The squeaky wheel gets the grease.”

Or, in this case, thanks to squeaky Iannece, Oakland Lake didn’t get the grease.

Iannece lives in Bayside Hills, a neighborhood near Oakland Lake, a spring-fed body of water that dates back to the last Ice Age; the parks department says it is the only one in Queens. Once teeming with wild fish and birds, it now serves mainly as an aesthetic backdrop for local joggers and a cement-lined way station for Canadian geese. Yosemite it's not, but in a corner of New York City dominated by the Cross Island Expressway and Northern Boulevard, it's a sentimental reminder of the days when canoes, not SUVs, were the primary mode of transportation in this corner of the city.

The problem facing the neighborhood was how to avoid the flooding to which the area was prone without emptying the runoff into Oakland Lake, which would then be contaminated with the toxic mixture of flood water, motor oil, fertilizer and other pollutants.

Engineers said the city would have to build a mile-long diversionary sewer pipeline, which would empty into the Little Neck Bay instead. Federal clean water regulations, meanwhile, demanded a new stormwater treatment facility. The price tag for the whole project would be as much as $160 million.

"Some people said that with that kind of money we should have just bought the dozen or so houses," says Iannece. "But if we did that, we'd be destroying a community. My response was, the city allowed this problem to happen. The city can fix it."

Elected president of the Bayside Hills Civic Association in 1996, Iannece at first used his newfound authority to press the Department of Environmental Protection to put its diversionary plan in motion. He also used it to lobby local residents on Springfield Boulevard and 46th Avenue, the two streets that would have to be torn up to make room for the new sewer pipeline. Most importantly, says Iannece, he courted prominent local politicians such as former Queens Borough President Claire Schulman and State Senator Frank Padavan, people with the power to move bureaucratic mountains with a single phone call.

"Jerry was extremely helpful," says Padavan. "In addition to reaching out to the community at large and getting me involved, he helped us overcome hurdles that would have kept the project from going through."

Among the chief hurdles was the Alley Pond Environmental Center, a bird and plant sanctuary located near the original sewer's untreated outfall. If the city had gone with its original plan, it would have dumped water into an area currently home to meadows and salt marshes. "Ecologically, it would have been a disaster," says Dr. Aline Euler, education director for the Alley Pond Environmental Center.

To keep waterborne pollutants from overwhelming the sensitive Alley Pond and Alley Creek ecosystems, city engineers agreed to move the sewer pipeline to the west, running it under Northern Boulevard.

As part of the compromise plan, the Department of Environmental Protection has also agreed to build storage tanks to capture water in low flow periods so that pumps can redirect that water to the Tallmans Island wastewater treatment plant for processing.

Meanwhile, both Euler and Iannece are looking to the project's final hurdle: the environmental remediation of Oakland Ravine, a portion of the Oakland Lake park which, thanks to the construction of 56th Avenue to the south, has been largely cut off from its historical watershed. A year ago, the Department of Environmental Protection appeared to waver on plans for a $10 million filtration system to handle the fast moving water coming down off the Queensborough College campus. Padavan brokered a meeting between Iannece and department officials. Both sides agreed to a more modest plan proposed by the parks department. The new plan uses parkland vegetation and "step pools" to filter out whatever contaminants work their way into the groundwater before that water hits the lake.

Euler, for one, is skeptical. "They really need to do a major job from an ecological standpoint, a sensitive design that takes into consideration trying to restore that lake to the way it was,” she says. “That lake was 15,000 years old and was working fine when the native Americans lived there. It was fine with the colonists. I hope that they do spend some money to improve it and restore it to the way it was."

Noting a century's worth of urban development, however, Iannece doesn't see that sort of remedy in the cards. He does, however, see the potential for something similar to the Staten Island Bluebelt, where park rangers have been able to bring back a semblance of native wetland amid an otherwise urban environment. Recent rumors that the Oakland Ravine portion of the project might fall out of the budget again have steeled his resolve to see it restored to a semblance of its native form.

"I think I might have to start kicking some butt again," he says.

While he doesn't consider himself an environmentalist, Iannece says he does think environmentalists and civic groups can work together to find more sustainable solutions to the man-made problems currently dogging the city. Advising other neighborhood groups on how to fix their own local problems, he keeps the advice simple: Start small, stay focused, and set yourself at least a five to ten year timetable for change.

"It's kind of like a war of attrition," he says. "I've been in rooms where 300 people would get up and yell at me. Still, if the community's focused, if the rhetoric is good, if the message is good, if the plan is good, you'll get the job done."

Planting Trees For Life

Hunts Point in the Bronx has an alarming number of children hospitalized for asthma -- the second highest rate in the city. It also has one of the lowest number of trees of any neighborhood in the city -- until recently, just one street tree per acre. Neighborhood activists saw a connection between the two statistics, looked at all the sources of pollution in the area – the 10,000 trucks that travel it daily, for one -- and formed a group called Greening for Breathing. Their goal is to plant a canopy of trees.

Hunts Point is just one of the neighborhoods with low-income, minority populations that have more pollution, more health problems, and fewer trees than the city as a whole. The average amount of land covered by trees in New York City is about 18 percent. In Hunts Point, canopy cover is 3.5 percent.

Trees lessen pollution by absorbing gases and intercepting particulates (the soot on the windowsill). By cooling the ground and filtering sunlight, they reduce the formation of ground-level ozone. In 2000, New York City’s street trees removed 1,500 metric tons of air pollution, according to an estimate by David J. Nowak, a scientist at the U.S.D.A Forest Service’s Northeastern Research Station. Studies (in pdf format) by Nowak and others have determined some of the variables that affect how much pollution a tree will remove, including its size, species, and location. For example, large trees remove about 70 times more pollution annually than smaller ones. An analysis by the Forest Service and SUNY’s School of Environmental Research of a survey done in 2003 found that just 322 trees in three New York City neighborhoods annually removed more than 500 pounds of pollutants from the air.

Street trees have many other benefits. They reduce energy use by shading sidewalks, buildings, and cars in summer, and buffering winds in the winter. They absorb greenhouse gases, slow stormwater runoff, and provide habitat for wildlife. Houses on leafy streets have higher real estate values, and trees in front of stores encourage pedestrian shopping. Research has shown that street trees create hospitable spaces — outdoor rooms — that bring neighbors together, resulting in stronger communities and lower crime.

Together with the city parks department, the group in Hunts Point came up with a detailed strategy (in pdf format) to survey existing trees, identify the best locations for new ones, plant them, and help them survive to maturity. They have planted 400 trees so far, and plan to plant an additional 75 a year for the next five years. "Eventually we’re going to have what I call an awning around us,” said Eva Sanjurjo, who has lived or worked in Hunts Point most of her life and was one of the founders of Greening for Breathing. “The awning is the trees."

Stitching together that awning is a slow process that requires a tremendous amount of legwork. The city will plant a tree on a sidewalk only if the owner of the adjacent property requests it, so volunteers have to find property owners and persuade them to submit a request. Because the parks department lacks the funding to care for trees once they are planted, a key part of the effort has been to recruit volunteers within the community to water, weed, and keep garbage from piling up around the newly planted trees, especially in the first few years when a tree is most vulnerable. To prevent vandalism and encourage stewardship, the plan includes special tree-planting days, workshops, and celebrations. "You can’t just plant trees and then you’re done — that’s the easiest way to fail," said Elena Conte, the group's coordinator. "What we’re working for is a much richer involvement."

As part of its current focus on the relationship between trees and public health, the parks department would like to replicate the Hunts Point project in ten communities around the city, and is working with the Department of Health to identify the locations, according to Fiona Watt, Chief of Foresty and Horticulture at the parks department. "Our focus and interest right now is how do we target our tree preservation, maintenance and planting programs to best support this emerging relationship and to improve public health in the areas that need it most."

A QUESTION OF FUNDING

The tree-planting efforts in Hunts Point as well in several other tree-poor areas around the city have been funded in part by the state, which has increased its support for urban forestry in recent years. Previously, the only money available for state urban forestry programs came from the federal government. In 2000, for the first time, New York began appropriating state funds for urban forestry, through the Environmental Protection Fund. Governor George Pataki singled out urban forestry as a priority in his State of the State address last January. Funds have also come from two separate settlements negotiated by New York State Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, in which bus companies charged with illegal idling were required to spend a total of $147,000 for tree-planting in areas with high asthma rates and near public schools.

But state funding for urban forestry, totaling $450,000 over the last four years, still falls far short of what is needed, according to Nancy Wolf, executive director of the New York State Urban and Community Forestry Council: A survey of municipalities around the state, recently completed by the council but not yet published, showed "the need for tree-planting money is just colossal."

In New York City, the parks department receives less than half a percent of the city budget to maintain and run the parks, so very little money is available for street tree care. In 1997, the department instituted a regular block-by-block tree pruning program that reaches the city’s 500,000 trees once every ten to twelve years, but park advocates fight annually just to keep the money for pruning in the city budget. Ideally, trees should be pruned every seven years, if not sooner. Maintaining and protecting trees in other ways, like watering, monitoring for disease, and purchasing tree guards to fend off trucks and cars, is left to tree-loving citizens and non-profit groups like TreesNY.

The capital budget, which covers planting trees, has been more robust, although not nearly enough to substantially increase the city's overall street tree population. Funding has ranged from $7 million to $10 million a year for tree planting, except during last year’s budget shortfall, according to Watt. But the price of planting a tree has risen steeply, so the department is able to plant fewer trees for the same amount of money.

In many years, the department planted slightly more trees than it lost, although last year it planted 9,997 trees while it removed 11,412, according to the recently released Mayor’s Management Report.

In September, the City Council passed a resolution calling on the city, state, and federal governments to plant trees in "communities of color, communities of low income and communities with the highest asthma rates, that have historically had the fewest tree plantings." But it doesn't address the funding needed to achieve that goal.

"The city should start by spending $45 million, one-tenth of one percent of the city budget," said former parks commissioner Henry Stern. "That would give you a much stronger program than you have now."

Efforts like Greening Hunts Point offer the hope of making life better and healthier in the city’s communities of color. But to bring trees into all the neighborhoods that need them most will take more than City Council resolutions and pilot projects. Urban forestry would have to become a citywide priority, with sufficient funding, for the city to truly green its grayest blocks.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

The Mayor's New Garbage Plan

|

Also: Related in Community Gazettes:

|

Unlike most New Yorkers, Carl Van Putten and Lilian Garcia pay attention to garbage after it is thrown away. They have little choice: their neighborhood, Hunts Point, is home to many of the city's "waste transfer stations" - sheds where garbage trucks dump trash so that larger trucks can pick it up and carry it out of state.

"The minute I came to Hunts Point my son developed chronic asthma," said Garcia.

On any given morning, as many as ten garbage trucks stand idling within a block of Van Putten's home on Hunts Point Avenue, where the breeze sends the smell directly towards him.

"I don't have polite words for it," he said. "You can call it a fragrance, aroma, or odor, but it's still a stink. It's heavy."

That is why they were happy to learn of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's solid waste management plan (pdf format), which would move most of the 50,000 tons of trash the city produces each day by rail or barge, instead of by truck. [For more about the plan's effect on the South Bronx, read Dumping Ground No Longer?in the Community Gazettes for the South Bronx].

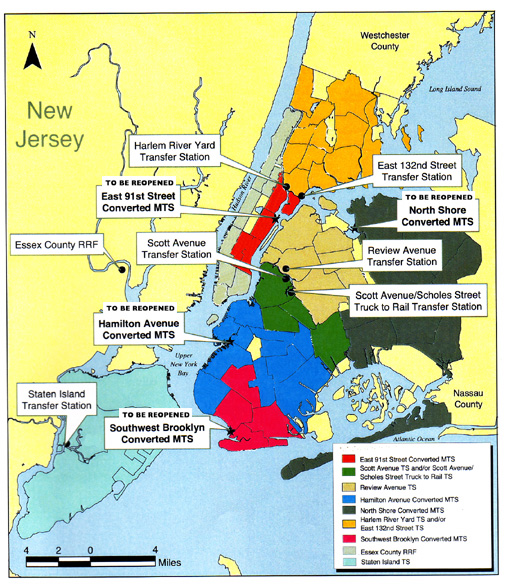

To do this, Bloomberg proposes to reopen four city-owned marine transfer stations, piers where trucks can dump trash onto barges, to handle the city's residential waste. The proposal is the third in a waste management plan that the mayor has rolled out over the last month:

- Recycling - The city signed a 20 year contract with Hugo Neu, a recycling company that will build a recyling station on the Brooklyn side of the East River.

- Commercial - A transfer station on 59th Street on Manhattan's West Side, is to be reopened to handle the city's commercial waste.

- Residential - Four transfer stations are to be reopened for residential garbage, one on Manhattan's Upper East Side, one in College Point, Queens, and two in Brooklyn (one in Red Hook and one in Gravesend).

The stations that the mayor wants to reopen were closed when the city stopped using Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island in 2001. Whether these stations handle commercial waste or residential waste doesn't matter much to those people who live near the stations; some don't see why the burden should now be placed on them.

"I know that the garbage has to go someplace," said Sandy Whitlock, who lives near the transfer station on the Upper East Side. "But it shouldn't have to impact a residential community." [For more, read The Garbage Returns to the Upper East Side in the Community Gazette].

Aside from complaints on the neighborhood level, some say the plan doesn't do enough to address the citywide trash problem. The prices the city pays to move its trash have risen substantially since Fresh Kills closed. Some out-of-state landfills that the city uses are nearing capacity, and the states where these landfills are located are often not much more interested in receiving the city's trash than are residents of the South Bronx.

Despite this, what the mayor describes as his comprehensive waste management policy stops at city limits, a shortcoming that experts like Benjamin Miller, former director of policy planning for the Department of Sanitation and author of the book Fat of the Land: Garbage in New York the Last 200 Years, see as its major flaw. [Read Miller's analysis, "The Waste Management Plan: Approve It, But Improve It"].

"The most important thing is where this stuff goes," Miller said, "and there's been no talk of that."

BURYING IT, BURNING IT, DUMPING IT

The challenge of dealing with garbage is not a new one to New York City. The city has long searched for an effective way to manage its waste - piling it onto islands, carting it to far-off lands, selling it to entrepreneurs, feeding it to hogs, burning it, or simply dumping it into the sea. Trash has been used as the foundation for airports, parks, and beaches. People trying to keep it from being shipped to their communities have proposed legislation and gotten into fistfights at City Hall to further their cases.

Many ambitious plans to manage the city's waste have not become anything more than words on paper. One supposedly temporary one, though, ended up turning into the largest manmade object on the planet.

When Fresh Kills landfill opened in 1947, it was slated to close within three years. Instead, it became the center of a citywide system that lasted until 2001. Sanitation Department trucks that collected residential waste and privately owned trucks that collected commercial waste would travel to one of eight marine transfer stations, where they would be emptied onto barges headed for Fresh Kills.

In the mid-1980s, the city raised the price of using these piers, and private companies built their own smaller truck transfer stations in places like the South Bronx and Northern Brooklyn. Trucks carting commercial waste transferred garbage to others headed out of state at dozens of these facilities. The city's residential waste, meanwhile, continued to go by barge to Fresh Kills.

In 1996, however, Mayor Giuliani pleased the Staten Islanders who made up an essential part of his political base by announcing that he would close down Fresh Kills. Consequently, the city-run marine transfer stations essential for the barge system were closed.

But by ending the Fresh Kills era without planning for the next, Giuliani left the city's own trucks with nowhere to go.

AFTER FRESH KILLS

The Sanitation Department began sending its trucks to the private transfer stations, where the trash they carried was dumped - or "tipped" - and reloaded, sometimes onto a train but usually onto a truck, and shipped out of state.

Private companies built these facilities based on their own business decisions, and the burden fell disproportionately on several neighborhoods. In a recent report (in pdf format), Environmental Defense, a national environmental group, found that 80 percent of the waste handled by private waste transfer stations goes to four of the city's 59 community board districts. "You have right now these stations located in neighborhoods where probably the land value was lower and the zoning was different. When [private companies] looked to set up those stations, [they] looked for those things," said Ramon Cruz of Environmental Defense. "Is that fair? No, but it's a function of the market."

The hundreds of trucks moving through these neighborhoods every day were not just smelly. Their weight took its toll on the roads, and their exhaust polluted the air. Asthma rates skyrocketed in areas where the stations were concentrated, a health effect linked directly to the garbage truck traffic.

Nor was this system particularly healthy for the city's economy. Shipping trash to landfills in Virginia or Pennsylvania was much more expensive than floating it to Staten Island. The per-ton contract for shipping garbage rose from $54 in 1997 to its present price of $74, a 40 percent increase over seven years. (If increased gas and labor prices are factored in, the increase is even larger.) The Department of Sanitation budget ballooned. Private companies saw their prices rise 50 percent over the same period.

Additionally, other states have resisted the city's garbage by imposing surcharges on out-of-state waste, and have passed laws to limit importation of trash. Federal legislation with the same goal has been introduced several times; there is currently legislation pending in both the House of Representatives and Senate.

To date, these laws have been overturned or rejected because they violate interstate commerce regulations, but they indicate the city's continuing vulnerability to events that are out of its control.

These problems are not secrets. But largely because any change in garbage policy alienates one political constituency or another, the city has faltered without a plan for years.

THE MAYOR'S PLAN

Over the last several weeks, Mayor Bloomberg has announced several proposals that, he says, add up to a comprehensive plan for dealing with garbage. The common element of his three plans is to shift from using trucks towards using barges and rail to move garbage out of the city.

To do this, the mayor intends to reopen four of the marine transfer stations that were closed along with Fresh Kills to haul the city's residential waste. Another station will handle the city's commercial waste.

The city's recycling will also be shipped via barge. The city will reopen a station at Gansevoort Street in Manhattan's meatpacking district, from which the recyclables will sail to a facility being constructed by scrap-metal company Hugo Neu in Brooklyn. The city also hopes to increase the proportion of its waste that gets recycled, to 25 percent of residential garbage by 2007 and then to 70 percent of both residential and commercial garbage by 2015.

The mayor has calculated that his plan to reopen the marine transfer stations for residential garbage will reduce truck traffic in the city by almost three million miles a year. This will have an obvious benefit for the city's roads; it will also reduce gas and labor costs and ease the environmental burden of waste management.

The city can count on its own trucks bringing residential waste where it would like. It cannot, however, simply force private companies to do the same with commercial waste. The Economic Development Corporation and the mayor's office are in the beginning stages of developing a system of incentives and regulations that will make its transfer station more attractive, while also raising the costs of running private transfer stations.

|

|

Clashing Communities

If the city can significantly reduce the use of private transfer stations, the negative effects of moving trash out of the city will be spread much more evenly, and the overall impact on the environment will be reduced. Community organizations and environmental groups that have long been calling for such changes are reacting positively to the idea.

Rare is the garbage plan that does not create resistance from those areas that will receive a larger burden, however, and this plan is no exception. Residents and local officials from the Upper East Side, represented by the mayor's chief political rival, Council Speaker Gifford Miller, object to the reopening of a station in their neighborhood. They say that the station's proximity to such a dense residential neighborhood is reason to keep it closed.

Miller makes a familiar argument: what is unhealthy in one neighborhood shouldn't be allowed in another. The Bronx and Brooklyn have used the same argument in their calls for Manhattan to handle it own trash; Staten Island periodically threatened to secede for decades, its residents' aspiration to become a separate city inspired largely by the feeling that the rest of New York was dumping its trash on their borough.

Bloomberg is unconvinced that the Upper East Side will suffer unfairly. "Every single part of this city has to participate in solving a very difficult problem," he said in response to Miller's objection, adding that the East Side produces a fair amount of residential trash and the facility already exists. "Nobody wants to have solid waste near them, but somebody's going to have to ... [Y]ou are limited to where you can site facilities."

While the mayor insists that politics did not fit into his decision to open this particular station, he does seem to have set up a political confrontation that could work to his advantage - hardly a rare move for politicians dealing with New York City's garbage.

An Expensive Plan With Dubious Economic Benefits

Bloomberg estimates that opening the marine transfer stations will cost $340 million, $85 million each. The total investment is actually larger, since the price of revamping the station for commercial waste or the operating expenses of these facilities are not included in this figure. (The recycling plant, on the other hand, is being built by Hugo Neu at no cost to the city; the contract by which it will handle the city's recycling is estimated to save $20 million annually).

The proponents of the plan are not promising a miraculous reduction in cost, though.

"It's not going to get cheaper; let's not kid ourselves," Sanitation Commissioner John Doherty said at the press conference where the details of the plan were announced. "What [this plan] is going to do is stabilize the costs."

But critics question whether it will even do that. A few large companies already run the waste management industry. According to the city Comptroller's office, 91 percent of the trash headed for landfills is controlled by one of three companies. Since a limited number of facilities can accept trash from barge or rail, the city may be making itself even more vulnerable to an uncompetitive market by relying solely on these two forms of transportation.

This problem underscores what critics say is a major weakness in the city's new plan: a failure to figure out where the garbage will go after it is shipped out of the city.

WHERE OUR GARBAGE GOES

The plan in its current form carefully itemizes how trash from each borough will leave the city. But the most distant destination it mentions is the Essex County Resource Recovery Facility, an incinerator in Newark New Jersey that converts a good portion of Manhattan's waste into energy. Newark is about 12 miles from midtown. But almost half of the 15 million tons of waste the city generates each year is sent to landfills in either Virginia or Pennsylvania, with some trucks driving as much as 1,300 miles roundtrip.

These trips are expensive, and are bound to get more so as gas prices rise, the landfills in other states fill up, and states continue to look for ways to keep New York City garbage out.

The effort of other states "is not slamming the door completely, but it's making the doors smaller, and it's making the price higher," said Benjamin Miller. "That's going to keep happening forever, and the only way to solve that problem … [is] to have a landfill in New York State."

The city comptroller's office agrees. In a report published this month (in pdf format), it advocated an in-state landfill. Although communities often don't want landfills, dumps do bring economic benefit, the report argued, and it makes sense to have that economic benefit go to New York State. In addition, a landfill in New York State that the city itself controlls would shield it from the anti-importation regulations in other states, and might even curb the enthusiasm to pass such laws.

For their part, the mayor's office and the Sanitation Department say that they sent a query (in pdf format) to upstate communities earlier this year asking them to consider a landfill for New York City waste and received no responses. Critics say the lack of interest is a result of a request so vague that it was impossible to take seriously.

WILL THE LATEST PLAN BE IMPLEMENTED?

Even under the best of conditions - if the City Council approves the plan, and the revamping of the now-closed stations goes according to schedule, and the commercial carters agree to use the city's facilities instead of their own - the new system will not be in place until 2007.

But plans dealing with garbage in New York City rarely enjoy the best of conditions. Big ideas tend to emerge, meet public resistance, fade away, and then sometimes re-emerge years or even decades later. Mayor Bloomberg himself announced a plan to reopen all eight marine transfer stations two years ago that quickly disappeared; Mayor Giuliani's comprehensive plan for garbage similarly vanished. Burning garbage used to be commonplace, but after spending a good deal of the 1990s planning for an incinerator at the Brooklyn Navy Yards, city officials now consider such facilities unspeakably bad ideas.

One big reason for this inability to latch onto a permanent solution, some say, is the public attitude. New Yorkers do not want to take responsibility for their own garbage. This helps explain, anthropologist Robin Nagle has pointed out, why sanitation workers might as well be invisible. They know more about any city neighborhood "than the most sophisticated sociologist just by observing what it discards," Nagle wrote in a recent online diary about her experiences working alongside NYC sanitation workers, "but no one [cares] about their insights. In fact, no one [cares] much about them at all."

The Waste Management Plan: Approve It, But Improve It

|

Also: Related in Community Gazettes:

|

The administration's new waste-management plan represents an important step in the right direction. It deserves to be approved. But it also deserves to be improved in a number of strategic ways that will make it truly cost-effective in the long run. Getting control of the facilities where our waste will ultimately be disposed of is the most critical of these strategic objectives.

THE PRIVATE SECTOR

Since the Fresh Kills landfill closed in 2001, New York, for the first time in its history, has depended on facilities in other states for the disposal of most of the 50,000 tons of solid waste it produces every day. The quarter of this material that the city's Sanitation Department collects is handed off to a highly organized private waste-disposal industry, in which a handful of firms own most of the country's available landfill capacity.

The per-ton fee charged by these not-so-benevolent oligopolists has increased, since the city started shipping garbage out of town in 1997, from $54 to $75 per ton—40 percent in seven years--while the fees paid by private businesses have increased by 50 percent. This steady climb, which affects not just New Yorkers but all our neighbors on the eastern seaboard who share access to the same landfills we use, is projected to continue in the decades ahead. To keep up with increase in cost, the city would have to lay off 300 or so full-time municipal workers every year.

OTHER STATES

If the sellers' market we blindly walked into with the unplanned closure of Fresh Kills were not enough, the severely tried patience of government officials in other states—New York State exports more refuse to place in landfills out-of-state than it puts in those within its own capacious boundaries—will further decrease our options. In 2002, Pennsylvania (which accepts roughly half of our waste) imposed a $4 per ton tax on all waste entering its landfills; in 2004 Governor Edward Rendell proposed increasing that tax by another $5 per ton.

After the announcement of Fresh Kills' impending closure, Virginia passed a law forbidding the import of out-of-state waste. That law was promptly struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court, as all such prior attempts had been, as a violation of the constitution's interstate commerce clause. But the failure of local initiatives does not preclude the eventual passage of some federal measure to limit the interstate shipment of waste, something that Congress in the last decades has seriously considered doing.

Moreover, there are perfectly legal means of excluding other states' waste—all that is required is having the public sector assume control over landfills, as Rhode Island and Delaware have done, or promulgating regulations that restrict the development of new landfill capacity, as South Carolina has. While it is not likely that New York's access to out-of-state landfills will be completely closed in the foreseeable future, it is inevitable that over time the export window will be narrowed. And equally inevitably, this will mean that disposal prices will increase even further.

NEW YORK'S OWN LANDFILL

The only viable long-term solution to this problem—as a compelling report (in pdf format) issued last week by City Comptroller Bill Thompson makes clear—is to develop or procure public waste disposal capacity, preferably in New York State, but wherever it is available on a cost-effective basis and easily accessible by the barges or railcars that impose much lower environmental and economic costs than trucks do.

And while some of this must be landfills (since there will always be some waste that cannot be managed in any other way), we also should use waste-to-energy facilities, which produce fewer adverse environmental impacts do landfills and are more cost-effective. (This is why the portion of the administration's recently released plan (in pdf format) that involves a long-term government-to-government contract for continued access to the Newark incinerator that already processes much of Manhattan's waste is a particularly good idea.)

OTHER ISSUES

While we are developing or procuring this publicly controlled waste-disposal capacity, there are other immediate steps we should be taking to reduce the volume of waste we must export and the cost of transporting it to its remote disposal locations.

One of these steps, as the comptroller's report makes clear, is using the city's contracting leverage to directly procure transportation services from the railroads. This is critically important for two reasons. First, if it does not do it, the city will inevitably pay much more—including a significant commission to the waste-industry middleman—than it would pay by negotiating a per-ton-mile transportation-services contract itself. Secondly, the logistical difficulties involved with contracting with the railroads represent a barrier that would exclude many smaller landfill operators, whose bids are essential if we are to enjoy a semblance of free-market competition.

The other thing we should do immediately is develop fair economic incentives for reducing the volume of waste that New Yorkers generate. (We should not try to reduce our waste volumes by using in-sink garbage disposals, either for residences or businesses, since this only increases public-sector costs and adverse environmental impacts.)

The single most effective way to do reduce garbage, as the experience of thousands of U.S. cities demonstrates, is by “metering” waste. Rather than having their waste-management costs buried within the city's general tax structure, New Yorkers would get an upfront deduction on their property-tax bills and would instead pay for having their waste removed by buying special bags or tags or paying on some other volume-based basis. Conscientious householders would thus save money relative to their current hidden tax payments and would no longer have to subsidize the wasteful habits of their neighbors.

Benjamin Miller, author of Fat of the Land: Garbage in New York, the Last Two Hundred Years (Four Walls Eight Windows, 2000), is a senior fellow at the CUNY Institute for Urban Systems.

The New Garbage Plan; New Worries About Flooding

New Garbage Plan

The major effect of the city's latest Solid Waste Management Plan, announced at a press conference this month by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Department of Sanitation Commissioner John Doherty, is to cut down on truck traffic through the city.

The city seeks to "retool" at least half of the eight "marine transfer stations" that have been largely idle since the closing of Fresh Kills landfill. Trucks have been shipping the garbage to out-of-state landfills since then. Now, sea-going vessels (and railroad cars) will do the shipping. Bloomberg estimated the elimination of at least 625 truck trips daily. "This would result in close to three million fewer truck miles on city streets."

Of course, this is not exactly comprehensive; the mayor's office has yet to find a way to reduce the city's mammoth residential trash load, currently averaging 12,000 tons a day. But the plan would at least reduce fuel consumption and truck-borne exhaust, two environmentally deleterious side-effects of the current trash-exporting system.

For more on this, see The Mayor's New Garbage Plan.

The Flood Next Time

Last month's torrential rains have once again reminded New Yorkers that while hurricanes generally do the bulk of their damage in places like Florida and North Carolina, they can still wreak plenty of havoc this far north. Remnants of Hurricane Ivan managed to shut down a dozen subway lines when flooding tunnels in Brooklyn and Manhattan imperiled the electrified third rail. On Sept. 28, remnants of Hurricane Jeanne disrupted service in a similar fashion out in Queens.

Such flooding leads to the natural question: What would it be like if New York City bore the brunt of the hurricane as opposed to the tail end?

Don't laugh. Two hurricanes hit the city in the 19th century and flooding from the lone 20th Century hurricane, the so-called Great Storm of 1938, killed more than 200 people on Long Island and parts of New England. According to Queens College geology professor Nicholas Coch, an expert on historical weather patterns, the city averages one major tropical cyclone a century.

"In the south they get a lot of hurricanes so it's easy to predict," says Coch. "Up here it's less predictable, so the more historical data we can gather, the better idea we have."

While the region may not have as many storms as Florida or North Carolina, those that do make it this far north pack a punch. Coch says the two hurricanes that hit the city in the 19th century most likely would have qualified as category two storms in terms of wind speed (96 to 110 miles per hour) but delivered broad regional damage equivalent to a category three storm.

"[Northern lattitude hurricanes] tend to have a larger wind field, move faster, and create very high surges."

Coch says the angled New York-New Jersey coastline tends to funnel storm energy onto local beaches and harbors. In the case of the city, the Verrazano Narrows acts like a meteorological megaphone, amplifying whatever storm waves make it through. In the 1821 hurricane, water level readings at the Battery showed a 13 foot rise in a single hour. "That was at low tide," Coch notes. "If the storm had hit during high tide, things would have been a lot worse."

New Yorkers who face down a hurricane in the 21st century might not be so lucky, even at low tide. Vivien Gornitz, a Columbia research scientist, studies sea level rise. Currently, she sees local waterways rising at a rate of 2.5 millimeters per year, 50 percent higher than the worldwide average. She expects that rate to accelerate in the coming decades as global warming draws more water out of mountain glaciers and polar pack ice and transfers it to the world's oceans.

"Whatever surge you'd see [in a future hurricane] would be superimposed on a higher sea level," says Gornitz. "With various levels of sea level rise, what we now consider 100 year storms could occur more often."

Put another way, the kind of local flooding that residents and insurance companies could pass off as a once-in-a-lifetime event may soon become a once-a-decade occurrence. Worst case models show a 10 foot rise in sea level, enough to cover the streets of Coney Island, Midland Beach, and Chinatown, hitting with a frequency of once every 5.5 years by 2080, assuming no change in coastal defenses.

Admittedly, 2080 is a long way off. Barring a major hurricane, Gornitz says the effects of climate change will look a lot like last month: Small storms will pack a bigger punch, resulting in more commuter and homeowner hassles and, over the long haul, readjusted flood insurance premiums, zoning and building-code changes designed to limit New Yorkers' flood exposure.

"I don't think it's going to be a sudden calamity," says Gornitz. "It's just going to magnify what we're already seeing."

Clearing the Air

With all of our focus on the war in Iraq, the upcoming elections, and the administration's ever-vacillating orange and yellow terror alerts, we New Yorkers may not be putting a mundane topic such as pollution very high on our list of worries. But while the problem may not grab our attention like a war, persistent environmental hazards in places like the Bronx are taking the lives of our children just the same.

Policymakers have the power to address these problems, but often seem to lack the will to. In Congress, we need to maintain tough standards and fund research to find technological solutions to environmental problems, while also tackling systemic issues such as access to health care.

HEALTH PROBLEMS IN THE SOUTH BRONX

The numbers are disturbing: New Yorkers suffer from the worst rates of asthma in the country, with over 10 percent of schoolchildren and more than 6 percent of the total population affected by the chronic respiratory disease. New York, along with Chicago, leads the nation in asthma deaths. Conditions are especially bad in the South Bronx, where 20 to 25 percent of schoolchildren suffer from asthma. Children in the area are hospitalized for asthma at a rate 250 percent higher than the rate for children in the rest of New York City, and 1000 percent higher than the rate for children in New York State as a whole.

South Bronx residents also cope with abnormally high rates of other respiratory illnesses, infant mortality, and immune deficiency disorders, while living in unhealthy conditions and having poorer access to healthcare.

Several local factors contribute to the pollution behind the respiratory illness epidemic. The South Bronx, besides being surrounded by highly trafficked highways, is home to a disproportionate share of the city's waste transfer stations. It is also a center of industrial activity. As a result, diesel trucks are omnipresent, creating dangerous levels of air pollution. The pollution from these trucks has been specifically linked to severe asthma attacks.

In low-income communities, health problems can quickly turn into social ones: Asthma, for example, is the number one cause of student absenteeism in New York City schools.

FUNDING RESEARCH AND GREEN SPACE

Since 1998, New York University, with cooperation from the local community, has conducted the South Bronx Environmental Health and Policy Study. The study, which I secured funding for, analyzes the environmental and public health effects associated with living near pollution sources, including waste transfer stations and major expressways.

So far, the study has observed the following:

• Hourly concentrations of diesel exhaust are higher at all of the South Bronx sites that have been tested than at the sites tested in Manhattan.

• Street level air sampling, using the study's mobile van laboratory, reveals that the concentrations of nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide are substantially higher than samples taken from rooftop monitoring sites. Air pollution is often more severe closer to the ground, and so it is important that it be studied where people actually are (on the ground), rather than just on rooftops, where it has traditionally been measured.

• Levels of most pollutants in the South Bronx are below U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards, with the exceptions of ozone and particulate matter.

• There is a strong association between zip codes with high asthma rates and those with a high number of industrial facilities, such as the waste transfer stations that are found all across the South Bronx.

The study is still underway. Its findings will help local policymakers better understand the relationship between air pollution and public health in the South Bronx. A series of papers written during the study are available at http://www.house.gov/serrano. Future research will examine demographic variables such as property values, poverty, and median household income to see what kinds of people are more likely to live close to dangerous waste transfer stations.

Students have already helped to disseminate the findings of the air pollution study to community leaders and residents and will continue to do so. These young people are participants in a program for high-school students from the South Bronx that gives them a chance to work with scientists and policy experts in public health and environmental science and to explore career opportunities in these areas.

TAKING ACTION

The findings of the South Bronx Environmental Health and Policy Study underscores how poor people bear a disproportionate share of the burden of our city's air-borne disease. Much needs to be done to address this injustice.

The first step is to enforce the clean air regulations that we already have in place. Unfortunately, the Bush administration has been working to systematically relax the tough standards of the Clean Air Act. While Democrats and some moderate Republicans have tried to challenge the administration in Congress, the Republican leadership of the House and Senate has refused to allow for the tough oversight that our citizens so desperately want and need.

GREENER PLACES, CLEANER TECHNOLOGY

In the most urban of American cities, our children must have access to open spaces where they can play and enjoy nature. But while parks make children's lives healthier and more fun, we should also pursue technological solutions to environmental challenges. Through policy initiatives, government can encourage the private sector to explore these possibilities. Using alternative, cleaner-burning fuels can go a long way in reducing the air pollution that afflicts our communities.

Alternative fuel technology development can also help to create jobs as innovative, more environmentally friendly companies provide economic growth and cleaner products. One of the great myths of our day holds that environmental protection and economic growth are incongruous. The Center for Sustainable Energy at Bronx Community College, which I helped fund, works to dispel that myth, showing the connection between growth and protection through education, training, and community engagement.

Congress needs to do more to combat the devastating effects of air pollution on the health of Americans. To that end, I have sponsored legislation to provide tax credits to businesses that use clean-fuel vehicles in high pollution areas. I have also co-sponsored the "Clean Smokestacks Act of 2003" that would amend the Clean Air Act to require the reduction of emissions from electric power plants. Unfortunately, the Republican Congressional leadership has not allowed these bills to advance through the House.

BETTER ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE

These are the sorts of measures we need to help reduce the environmental problems in places like the South Bronx. But from Boise to Brooklyn, asthma and other respiratory diseases would not be so damaging if we had universal health care in our country. Disadvantaged Americans are paying for our nation's disparities with their health and their lives. If asthmatics received proper preventative health care, they would be able to better manage their asthma and get access to the medication they so desperately need. Government needs to do more to expand access to health care and to encourage people to use the services already available.

As it stands now, many of our kids only get their asthma treated when it becomes so bad that they have to go to the emergency room. Studies have consistently shown that the amount we pay for emergency room visits costs more than it would to provide better preventive care. For these reasons, as well as in the interests of basic social justice, we must continue to fight to build an America that is not the only industrialized nation in the world without universal health coverage.

The challenges ahead of us are myriad and daunting. But if we truly believe in an America of equal opportunity, we must work to reduce the glaring environmental and health disparities that continue to afflict our needy communities.

José E. Serrano, a Democrat, represents the 16th Congressional District. He serves on the House Appropriations Committee and is a member of the Children's Environmental Health Caucus.

Â

Recycling Food Waste

New York City recycling has rallied in the last two years. Glass and plastic are back. Paper never left. Even local sewage, once decontaminated, is finding a productive use as organic fertilizer -- albeit with lingering odor and safety issues .

The next obvious target is food waste. New York leads the nation in wasting food. Up to 40 percent of the city's garbage every day are old bones and bologna sandwiches. One reason is the vast number of restaurants here - almost 18,000. But even the percentage of residential waste that are old food scraps is higher here than the national average (almost 13 percent here compared to 10 percent nationally). Residents of other cities stick their food waste in their backyard, creating nutrient-rich composting; too much of New York doesn't have such backyards. Food scraps that would be ground down kitchen sinks in Los Angeles or San Francisco end up at the curbside in Brooklyn or Manhattan.

Attempting to recycle more organic waste - food scraps and yard material -- would fit in with what is reportedly a new tilt in the city's waste management strategy. The New York City Department of Sanitation is scheduled this fall to present to the New York City Council its latest Comprehensive Solid Waste Management Plan, outlining what should be done over the next 20 years to handle the city's garbage. There are some clues that the city is looking to lessen its dumping bill by recycling more waste.

This fall the Department of Sanitation will resume passive yard waste collection at three facilities: Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island, Spring Creek in Brooklyn and Soundview in the Bronx. In the case of food waste, however, the only current recycling options for most residents and businesses are the local community garden programs that offer limited scale composting.

Barriers to expanding such voluntary programs are sizable. Christine Datz-Romero is a co-founder of the Lower East Side Ecology Center, a neighborhood program that currently recycles more than 60 tons a year of food waste. The program sells 10 tons of compost a year to local garden supply shops. The center hopes to expand -- it is currently exploring a plan to provide curbside pickup for the area encompassing the entire local community board - but Datz-Romero says that it won't be easy, given the need for permits, funding, and so forth. "If you started the process today, you would open the door on your facility in between three and four years -- if you're lucky."

Some are hoping the city will reconsider another alternative: food waste disposers. More commonly known as grinders or garbage disposals, and placed in kitchen sinks, these food waste disposers have been legal citywide since 1997. Most people don't know this, however, thus limiting their use.

Kendall Christiansen, spokesman for In Sink-Erator, the nation's largest manufacturer of food waste disposers, points to a late-1990s study by the Department of Environmental Protection, the agency responsible for overseeing the city's sewer and sewage treatment systems. According to the study, some 30,000 new disposers could be installed each year without overloading the city's sewage system. So far, city sales are far below that rate.

"We just did an informal survey this summer that found not quite half of building developers were installing them in new buildings under construction," says Christiansen. "When I get into conversations with landlords and developers what they routinely tell me is, 'Hey, we get free garbage collection. Why should I spend an extra hundred bucks to put in a food disposer?'"

Making food waste disposers mandatory in these new apartments would technically fall under the umbrella of recycling, since a sizable portion of city sewage is converted into organic fertilizer for commercial use.

But even the Department of Environmental Protection seems resistant; even after giving food waste disposers the green light, it still has not endorsed any law that would make their use mandatory. When the City Council's Sanitation and Solid Waste Management Committee held hearings on such a proposal this spring, department representatives argued that the plan would force them to double the city's sewer maintenance budget to $100 million.

Composter Datz-Romero is also leery of relying too heavily on these kitchen grinders . She notes that they require water to liquefy food waste. "We should be saving our water for drinking, in case we have another drought," she says.

Composting advocate Tom Outerbridge, on the other hand, sees nothing wrong with a Solid Waste Plan that encourages both options -- commercial composting and mandatory food waste disposer use. Architect of the Rikers Island composting program that currently recycles 20 tons of prison food scraps annually, Outerbridge sees the economic playing field shifting in favor of food waste recycling. He points to the Business Integrity Commission's recent decision to up the limit on carting charges for private trash-haulers from $25 per ton to $160 per ton. While hard on local restaurants, such an increase removes the penalty on carters who specialize in heavier, water-laden food waste. As such, it should free them to invest more in the local facilities that can make composting a more viable option. In the meantime, food waste disposers can take a sizable portion of the trash burden off the top.

"Assuming the city is able to divert its biosolids to some kind of beneficial application and assuming that the sewer system has the capacity. I think food waste disposal and the sewage system are a very efficient way to get food waste back into some beneficial use," he says.

And, says Outerbridge, if the city were to finance the construction of large scale composting facilities locally -- just as it did for residential paper recycling -- the economic playing field could tilt even further in the favor of food waste recycling.

$243 Million For Bronx Parkland? Who Will Decide?

Â

City and state officials are discussing how to spend a substantial amount of new funding for Bronx parks, but the public doesn't have a seat at the table. The money - $243 million promised as mitigation for building a controversial water filtration plant underneath a section of Van Cortlandt Park - is nearly triple the capital funding the city allocated for parks in the Bronx over the last five years.

Legislation that takes over parkland to use for some other purpose requires state and city officials to sign a Memorandum of Understanding identifying, among other things, a list of eligible projects. The state legislature approved the water filtration plant last year. The City Council is scheduled to vote on the memo and its list of projects in September.

Last year, Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe said that the department had a long list of Bronx park projects it was circulating, and that it would be going to community boards and other community groups to solicit their input on projects. But park organizations and advocates say there have been no public forums to discuss what projects should be funded, and that the final decisions are being made by politicians behind closed doors.

Ari Hoffnung, chair of the parks and recreation committee of Community Board 8, which includes Van Cortlandt Park, said, "To the best of my knowledge, the community board hasn't been contacted formally for its input on the mitigation funds," although they had some "very tentative" conversations about how the money could be spent in Van Cortlandt Park. "I would certainly welcome a request from the parks department or other appropriate city agency that would involve input from the community," he said. Hoffnung envisioned a forum where "park advocates, park users, and the community at large can come together and really voice their hopes and aspirations for the parks in the community." He said, "To spend $200 million without consulting the community is outrageous."

In early 2003, before the legislation passed, the parks department met with board members and Executive Director Paul Sawyer of Friends of Van Cortlandt Park, which opposes putting the filtration plant in the park. Officials presented the projects the department wanted to do in the Bronx, according to Sawyer. "We were kind of taken aback," he said. The group told the parks department that it was not prepared to talk about projects that early in the process. Friends of Van Cortlandt Park is continuing to fight the filtration plant in the park, and is planning a lawsuit.

According to Sawyer, some people present at the meeting pointed out that the projects were presented on a map broken down by Assembly district - seemingly a fairly blatant indication of what had been promised to Bronx Assembly members in exchange for their votes to approve the taking of parkland. The legislation passed in an extremely close vote after midnight at the end of the 2003 legislative session, and broke the Assembly's tradition of never approving the taking of parkland over the objection of the member who represents the area.

Looked at less cynically, many Bronx politicians felt that the opportunity to fund much-needed park improvements in an era of declining public funds outweighed the environmental impacts and parkland loss for one densely populated neighborhood.

Four environmental and parks organizations, both supporters and opponents of the filtration plant, sent a letter on August 4 to the elected officials who must sign the Memorandum of Understanding, asking for more citizen involvement in the selection of park projects. The groups - New Yorkers for Parks, New York League of Conservation Voters, Natural Resources Defense Council, and Environmental Defense - also called for "clear assurances" that the funding be in addition to the currently approved capital budget for Bronx parks and that the projects be chosen within a strategic, long-term capital investment plan. The letter cited a recent Ernst and Young study, How Smart Parks Investment Pays Its Way, which found that capital investment in parks had higher economic returns when it was part of a larger plan for the community and involved local residents and organizations.

Christian DiPalermo, executive director of New Yorkers for Parks, said that the groups had not gotten a response to their letter. "None of the elected officials seems to care what the public is thinking, but everybody looks to the public to maintain the parks," he said.

Will the money go to Yankee Stadium?

During the hearings last year preceding the legislature's vote, park advocates raised the possibility that the mitigation money could be used to pay for a new Yankee Stadium. Officials from the Department of Environmental Conservation and the parks department debunked that notion. At the time, Assembly member Scott Stringer, who voted in favor of the taking of the parkland, said, "That's absurd that it would be spent on Yankee Stadium."

Recently, however, The New York Times reported that the city and the Yankees are in discussions to build a new stadium at the site of Macombs Dam Park, adjacent to the current stadium. The Yankees intend to pay for the new stadium, now that taxpayers are losing patience with footing the bill for sports arenas. But the city would be expected to pick up the tab for a string of parks and ballfields leading down to the Harlem River to replace Macombs Dam Park. The plan fits in nicely with a plan for redeveloping the area being promoted by Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrion.

The Daily News reported that, according to two Bronx officials close to the negotiations, the final agreement on how the $243 million would be spent has been held up by a last-minute effort by Governor George Pataki to earmark some of that money for the new Yankee Stadium plan. However, Jennifer Meicht, spokesperson for Governor Pataki, said, "That is absolutely not true."

Meicht said, "Negotiations are ongoing to determine how the money will be disbursed," but did not have any information on plans for public participation. She added, "We strongly support that the money should be used for parks-related projects only."

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Trying to Clean Up New York

|

Related in Community Gazettes:

|

Five days a week, Albert Ridley and Jesus Negron appear on the Upper East Side at 7 a.m. to sweep streets, empty litter baskets and scrape illegal leaflets off lampposts. It isn't easy: The two men must cope with illegally parked cars that block their brooms, bags of dog poop that have not been sealed, and news vendors who dump piles of heavy newspapers into litter baskets instead of bundling them. But, they say, their work is appreciated. "People stop you and thank you for keeping the area clean," Ridley says.

Ridley and Negron, who both served time in jail, participate in the Doe Fund's Ready, Willing and Able for homeless people and former convicts. It is part of the patchwork of government and private programs that try to keep New York clean.

Despite such efforts, New York does not seem to have shaken its long-time reputation for being filthy: In a poll in 2002, almost half the visitors to New York (and more than half of New Yorkers themselves) said that the city's streets were dirty.

This is not the way it has to be in a big city.

"The biggest difference between New York and Paris is the fact that Paris is clean," David Garrard Lowe wrote in City Journal in 1996. Every morning, Parisian merchants hose sidewalks, and city machines spray streets and remove litter from under parked cars.

"The fact that Paris is clean gives Parisians a sense that things are not falling apart," said Lowe, "that society is not doomed, that there is order in the universe and municipal government."

New York City has struggled over the past decades to overcome its reputation. Now, says the Bloomberg administration, it has largely succeeded. A recent city survey (in pdf format) found 89 percent of city streets "acceptably clean" -- a higher percentage than at any time since the city began keeping records 30 years ago.

But the cleanliness of the city remains a heated political issue, as a recent furor over debris on city beaches makes clear. Critics doubt whether the city really is as clean as the administration claims.

And they question whether the city can claim responsibility for any improvement there has been. Private groups, such as neighborhood and civic organizations, play an increasing role in sanitation, picking up trash, bagging garbage, and cleaning up graffiti (see related stories on Kew Gardens Hills and Riverdale.) Does the city rely too much on such groups? Or should it turn even more over to private agencies?

CLEAN STREETS, HEALTHY STREETS

On one fact everybody can agree: The city is certainly cleaner than it was for much of its history. That is not difficult. For centuries the filth of New York streets was legendary, over-the-top, deadly. Efforts to clean it up had little effect, starting with the law banning the disposal of animal carcasses and other garbage in city streets in 1657. In the 19th century, residents dumped their garbage directly onto the street, attracting foraging dogs and pigs. By the end of the century, some 2.5 million pounds of manure fell in city streets every day, according to one estimate.

"Before 1895 the streets were almost universally in a filthy state," wrote George Waring, the man credited with improving the situation. "Rubbish of all kinds, garbage, and ashes lay neglected in the streets, and in the hot weather the city stank with the emanations of putrefying organic matter. It was not always possible to see the pavement, because of the dirt that covered it."

The city established the Department of Sanitation in 1881, but it remained mired in corruption. The situation came to a head when the blizzard of 1888 dumped 21 inches of snow on the city. Snow removal was haphazard at best, and once the snow melted, the city still had to take care of the garbage, including several hundred animal carcasses.

Several years later, Waring was named commissioner of the Department of Street Cleaning. He organized the department as though it was an army, cracked down on patronage and gave street sweepers white uniforms, leading to the nickname "whitewings." Two years later Waring would boast: "New York is now thoroughly clean in every part. . . ." "Clean streets means much more than the casual observer is apt to think. It has justly been said that 'cleanliness is catching,'and clean streets are leading to clean hallways and stair cases and cleaner living-rooms."

But as New Yorkers know, the city had not won the battle. Since the mayor's office began issuing ratings on street cleanliness in 1975, the results have fluctuated widely. In 1980, only 53 percent of the streets were considered "acceptably clean." Ratings improved steadily until they reached the low 70s in 1986 and remained there until the late 1990s.

But that was not clean enough. Garbage-strewn vacant lots and filthy streets blighted many neighborhoods. "New York is surely the filthiest of any major American city, the only one that does not have a single faultlessly kept area under city control," Julia Vitullo Martin wrote in City Journal in 1993.

But by the end of the decade, things had improved. Many areas seemed cleaner, and the rating rose to above 80 percent, where it remains today.

HOW CLEAN IS CLEAN?

To reach its findings on street cleanliness, the mayor's office of operations rates selected streets and sidewalks on a scale (in pdf format) from 1.0 (no litter) to 3.0 (litter is highly concentrated). But the method is not totally scientific, giving the mayor's political opponents the opportunity to question the findings.

The results of the most recent report card "seem like Alice in Wonderland," Councilmember Christine Quinn, whose district includes Greenwich Village and Chelsea, told the New York Post. "The number one complaint I hear -- I'm not exaggerating it -- at every block association meeting is dirty streets and litter."

This summer's biggest clash over cleanliness came not over streets but beaches, the responsibility of the parks department. In early August, the City Council issued a report stating, "New York City beachgoers who expect sun, surf and sand might also find condoms, hypodermic needles, food wrappers and other garbage littering both shore and sea." To bolster the claims about dirty beaches, the report featured photos including one of what appeared to be a dead rat, covered in sand, on Staten Island's South Beach.

Similarly parks advocates often point to dirty parks -- from simple litter to larger amounts of garbage dumped in remote areas.

Disputes arise as well over how to clean the city. The mayor and some council members have disagreed over sanitation tickets -- fines issued to businesses and homeowners that do not keep their property clean. Many who receive the tickets say they are penalized for violations that are not their fault -- Big Mac packaging on their front lawn dropped by customers from a nearby McDonald's, say. Earlier this year, City Council unanimously passed a bill that would allow the city to issue fines only during two specified hours, so homeowners would not face fines for litter dumped on their property while they were at work. Bloomberg vetoed the bill, but the council overrode the veto.

To combat the dumping in vacant lots of garbage, furniture, appliances -- even cars -- the city has increased the fines, and offered rewards for turning in people who are repeat offenders.

WHO CLEANS UP?

The primary responsibility for keeping New York clean lies with the Department of Sanitation, which has a budget of about $1.5 billion. The parks department cleans city parks and beaches, with the help of private parks groups and hundreds of volunteers.

But in many neighborhoods, residents complain that these efforts fall short (see related story on the Lower East Side). And so, a number of City Council members use their discretionary funds to fund clean-up efforts.

Last year, James Gennaro spent $35,000 for trash baskets in his district. Several council members, including Gennaro, have hired Ready, Willing and Able to clean the street. The program hires homeless people and former convicts for the job, paying them $5.50 or $6.50 an hour (tax free).

"It's a two-sided page," explained Craig Trotta, director of work and training for the fund. The neighborhood, he said, gets cleaner streets, while the workers get jobs that can help set them on a path to a a job and a place to live.

And then there are individuals who wage a war against litter. In the Ditmas Park area of Brooklyn, a long-time resident picks up garbage in her community. "I do it because I love the neighborhood," she said, adding that the area's small size makes it possible for her to have a real effect. "It's not a Herculean task," she said.

A combination of efforts go toward keeping a neighborhood clean, said Fred Arcaro of Community Board 6 on the East Side of Manhattan, an area whose streets have been rated the city's cleanest. The neighborhood hires the Doe Fund to help. Community associations keep pressure on businesses to clean up. "You have a civic culture here to keep the sidewalks clean," Acaro said.

A public-private mix also removes graffiti. While the city has an Anti-Graffiti Task Force that has removed more than 16.3 million square feet of graffiti since July 2002, community groups such as the Glendale Civilian Observation Patrol fight the paint scrawls in their own communities.

The Adopt a Highway Program took on the daunting task of keeping highways clean in the 1990s. Run by the city Department of Transportation, businesses, organizations or individuals commit to keep a stretch of highway clean -- either by caring for it themselves or hiring a maintenance firm to do it.

Business Improvement Districts also take up some of the burden. Businesses in a specified area pay an additional tax, the revenues from which go to improving the area -- which often means street cleaning, as well as better lights and holiday decorations.

Heather McDonald of the Manhattan Institute has hailed the Business Improvement Districts as "one of the most important developments in local governance in the last two decades." In 1996, she credited them with "considerable responsibility for turning around once squalid neighborhoods -- from Times Square to East Williamsburg, Brooklyn -- and making them safe and attractive for shoppers and pedestrians."

And some call for a greater private role in sanitation. The city instituted private garbage collection for businesses in the mid 1950s. In the 1990s, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani considered having private companies compete with the city to collect residential garbage. The plan lost steam when sanitation workers agreed to productivity measures. But the idea still appeals to some people, particularly political conservatives.

But some critics say government, not businesses or volunteers, should clean the city. Councilmember Eric Gioa, who hired the Doe Fund for parts of Woodside,Queens, told Newsday, "It's unfortunate we have to rely on a private organization to clean up our streets because cleaner streets should be a top priority of government."

The New York City Audubon Society has reservations as well. "There is a very unsettling trend in this city where city and federal government agencies have decided to abandon their responsibility to keep their facilities free of litter and dumping," the group's newsletter said.

NEW POLICIES

One way to have less garbage to pick up is to produce less of it in the first place. As evidence, advocates point to the bottle bill, which set a mandatory deposit on beer and soda containers. According to one estimate, the measure has reduced litter in the state by 70 percent. A bill introduced in the state legislature seeks to expand the law to include containers for bottled water, iced tea, juice and sports drinks -- beverages that barely existed when the law was first passed in 1982.

The New York WasteLess Campaign offers tips to help individuals, businesses and government cut down on garbage that can turn up as street litter. These include simple steps such as buying products with less packaging and bringing lunch in reusable containers.

Streets and lots are dirty largely because people make them that way. For some, littering reflects self-interest. People and businesses improperly dump garbage in a public place because they don't want to pay to dispose of it properly.

But for some litterers, it is not that simple. Psychologists have researched why some people remain impervious to entreaties, dirty looks and common sense and continue to drop scraps on the sidewalk and dump everything from coffee cups to old sofas in vacant lots.

A 1980 study concluded that people are more likely to litter on dirty streets than clean ones. People also tend to litter when they feel no sense of identity with an area (see related story on East New York). And, concluded Thomas Herblein, a sociology professor, "litterers are people who are less likely to feel personally responsible for their action. And they are less likely to be aware of negative personal consequences that litter hurts others."

Some officials have set out to change those attitudes. Last year, Gary Giordano, district manager of Community Board 5 in Queens (which includes Middle Village and Glendale), launched a campaign to highlight the role of the public in improving the cities. "So often," he wrote in a mailing, "the problems that our city has to solve are mainly due to people behaving badly."

Similarly, James Vacca, district manager of Community Board 10 in the eastern Bronx, wants to affect his neighbors' behavior. "I don't want people to think that because we are the Bronx, we are any different from Chappaqua," he told the New York Times. "We are people who have standards."

Urban Forestry's New York City Roots

It was 84 degrees in Manhattan with humidity just under 80 percent, but the hikers wouldn't know it standing in the middle of Inwood Hill Park.

With trees rising as high as 140 feet in the air, blocking out sunlight while leaving just enough head room to catch the occasional wind draft, they could feel the summer warmth, but didn't have to wear it like a blanket. Manhattan might as well have been a thousand miles away. But of course, it wasn't. Inwood Hill Park is in Manhattan.

"I'm pleased with it," said Tim Wenskus, a biologist with the New York City Department of Parks Natural Resources Group and the man in charge of making sure this forest in the northern tip of the island remains tranquil.

"You should be," said Mark McDonnell, associate professor and divisional director of the Australian Research Center for Urban Ecology. "You've done a great job."

Both Wenskus and McDonnell are urban foresters, a small but growing group of scientists who believe habitats such as this one are just as deserving of study and protection as anything you'd find in the Amazon rainforest.

The four men on the hike were having something of a reunion. In the 1980s, Mark McDonnell helped dig and document the many plots the group is now revisiting, in the city that provided a North American launching pad for the field of urban forestry 20 years ago.

"Traditionally, ecologists never looked at cities," said Richard Pouyat, who now works at the Forest Service. "We always looked at areas where people weren't living. Mark was really a pioneer of looking at cities as their own ecosystems. Twenty years later, people have come around to his point of view."

Trees do more than provide an aesthetic backdrop in city environments. Urban environments, once denuded of native vegetation, become dangerous heat conductors, a phenomenon called the "heat island" effect. Coupled with the heat displaced by air conditioners, urban environments like Manhattan average daily temperatures 10 degrees hotter than surrounding regions.

"If you want to see the effects of global warming, just look at any big city," McDonnell said. "At a local scale, it's just pure environmental change."