City Council Stated Meeting - November 16, 2005

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. Gotham Gazette covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

QUOTE OF THE DAY:

"The unions saved this city in the 1970s, they were part of the inception of campaign finance in the 1980s, and they should be given a fair and equal opportunity to have full participation [in the political process.]" - Councilmember Leroy Comrie on easing campaign finance restrictions for union donations.

MEETING SUMMARY:

CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS FROM UNIONS

New York City's Campaign Finance system, which offers candidates matching funds in return for agreeing to spending limits, has been hailed as a model for the rest of the nation. It is also a system that has benefited all 51 City Council members, who receive $4 for every $1 they raise in small donations.

On November 16, the City Council voted to amend the Campaign Finance law as it relates to donations from labor unions. The council says it is protecting city workers' interests; critics say it is giving too much power to organized labor.

Earlier this year, the Campaign Finance Board voted to prevent unions, who can give up to $2,750, from using their local affiliates to funnel additional money to candidates. Under the decision, a union like the Service Employees International Union could only give one donation to a candidate even though it is comprised of local groups like Local 32B and 32J, which represents maintenance workers, and 1199, which represents health care workers.

The council argues that the Campaign Finance Board went too far and is being unfair to workers, who have distinct needs and may want to support different candidates. For example, in the recent election, Local 32B-32J supported Mayor Michael Bloomberg, while 1199 supported Fernando Ferrer.

Under the council's bill (Intro 564-A), a candidate can accept multiple donations from a union and its affiliates as long as:

- the donations come from different bank accounts

- the unions maintain different signatories

- they have distinct governing boards

- and they do not share a majority of officers.

"This is an important effort to protect the rights of free speech of working men and women and protecting their ability to participate in the political process," said Councilmember Bill deBlasio, who authored the bill.

"The unions saved this city in the 1970s, they were part of the inception of campaign finance in the 1980s," said Councilmember Leroy Comrie, "and they should be given a fair and equal opportunity to have full participation."

But critics say that the council has created a loophole that gives labor unions too much influence. Newspaper editorials have called the legislation a "City Council Money Grab" and "a suck up to [labor] bosses."

The measure passed easily by a vote of 43 to 3; only Madeline Provenzano, Eva Moskowitz, and Andrew Lanza voted against it.

Councilmember Peter Vallone, Jr. abstained, calling it a "flawed bill."

Mayor Michael Bloomberg said he will veto the measure; the council has more than the 34 votes needed to override the veto.

PROPERTY TAX RATE

In an effort to shift the city's property tax burden from homeowners to commercial property owners, the council approved a change in the tax rates.

Although the citywide property tax has remained the same since Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council increased it by 18.5 percent in 2002, the state adjusts rates annually to keep pace with the real estate market.

The council's action lowers the state's proposed 7 percent tax increase for single family homes to 4.3 percent , which will save the average homeowner $80. It also increases taxes for Class A office buildings; the average building in Manhattan will see a $168,000 hike.

While most council members applauded the move, others complained that homeowners will still see an increase when their next bill arrives.

"While we can all be pleased that we are doing the right thing... the next tax bill they get will be more than the last," said Councilmember Lew Fidler. "I guarantee you at the end of December, my office and all of yours will be besieged with phone calls saying, 'How come you raised our property tax bill again.'"

The three Republican members - James Oddo, Andrew Lanza, and Dennis Gallagher - voted against the adjustment, arguing that property taxes should be reduced.

The council's action does not affect the $400 property tax rebate for homeowners, which the mayor has promised to continue next year.

PROTECTING RELIGIOUS PROPERTIES

In 2004, there were 350 documented Anti-Semitic incidents in New York City, according to the Anti-Defamation League. In response, the council passed a bill (Intro 703-A) increasing fines from $10,000 to $25,000 for vandalizing religious properties.

"I am not sure it will be a deterrent for a knucklehead who is so full of hate and stupidity that he desecrates a house of worship," said James Oddo. "It is intended to be a 'financial life sentence' of sorts."

SPORTS STADIUM CONDUCT

In 2003, the City Council passed a law making trespassing on professional sports playing areas a misdemeanor and increasing fines and penalties for those who violate the law.

The council strengthened its "sports stadium security policy" with a bill (Intro 528-A) that adds spitting, throwing objects, or physically hitting someone on the field to the regulations.

"Our families should not be intimidated by drunken idiots in any stadium," said Councilmember Peter Vallone, Jr.

RECYCLING BATTERIES

The council also approved new recycling programs (Intro 70-A) for rechargeable batteries.

"Rechargeable batteries have many toxic substances and people throw them away by the millions," said Councilmember Oliver Koppell. "They get into the waste stream, and they poison our land and our water."

Manufacturers and marketers of products that use rechargeable batteries will fund the project. Approximately 37,000 retail stores throughout the city and on the Internet, such as Radio Shack, Home Depot and Verizon Wireless will collect the batteries and send them to manufacturers. There is no cost to the city.

Only one member, Simcha Felder, voted against the measure.

PLUMBING CODE

The council approved a new 400-page plumbing code (Intro 478-A). It is the first part of an entire overhaul of the city's building code that the council's housing and building committee has been working on for much of the last four years.

DUMBO BUSINESS IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT

The council also voted to create a business improvement district (Intro 691) in the Brooklyn neighborhood DUMBO. Business improvement districts provide activities or amenities that promote business in a specific area, including maintenance and sanitation, holiday decorations and other efforts. They are funded by assessments on property owners within the area and overseen by the city's Department of Small Business Services.

All bills (except for the campaign finance, property tax adjustment, and the battery recycling program) passed unanimously by a vote of 48 to 0. Maria Baez, Phil Reed, and Larry Seabrook were absent.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for November 30, 2005.

Â

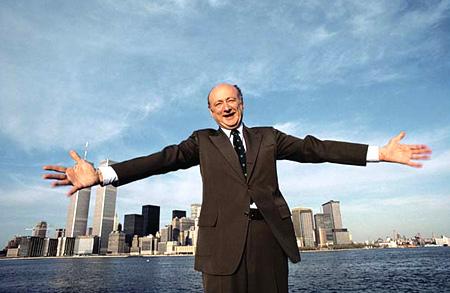

Ed Koch's Legacy

Michael Bloomberg has demonstrated that a mayor can “competently manage the city without building a personality cult at City Hall,” a commentator wrote recently. No one would say that about Ed Koch. “Mayor Koch was so in your face for so long that a whole generation of children grew up thinking â€Mayor’ was his first name,” said former Daily News editor Michael Goodwin.

Recently – 28 years after Koch won the mayoralty – a panel revisited the Koch years. They recalled a mayoralty that revived a city scarred by fiscal crisis, crime and decay. They paid less attention to Koch’s defeat in 1989, when voters, tired of the “shtick” and disgusted by corruption and racial tensions, ended Koch’s time in office.

The following discussion, moderated by Goodwin, featured journalist and novelist Pete Hamill; Stephen Berger, former director of the Emergency Financial Control Board; New York Times columnist Joyce Purnick; the Reverend Al Sharpton; and Victor Gotbaum, former executive director of the municipal workers union, District Council 37. The forum launched “New York City Comes Back: Ed Koch and the City,” an exhibition currently on display at the Museum of the City of New York.

This is an edited transcript of the discussion.

Intro - "The Good Fight and the Good Quip"

Pete Hamill - "Our Pain in the Ass"

Stephen Berger - "He Would Balance the Books"

Al Sharpton - "He Launched My Career"

Ken Auletta - "Entertaining Conflict"

Joyce Purnick - "The Unstoppable Ego"

Victor Gotbaum - "His Enemies Created Him"

Ranking Koch Among Mayors

Corruption and Scandal

What Koch Did Not Do

THE GOOD FIGHT AND THE GOOD QUIP

Michael Goodwin: In January it will be 28 years since Edward I. Koch first took the oath as the 105th mayor of the city of New York and 16 years since voters made him a private citizen. The 12 years in between were like no other in the recent history of the city. The Koch years were unique -- all the energy and change and drama. The fate of the city was at stake. It wasn’t just the finances sinking. It was the civic spirit that was sagging too. Once a great metropolis, New York had fallen and it couldn’t get up.

But it did get up -- because Ed Koch pulled it up. In a 1984 interview, the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan said, “Ed Koch has given New York City back its morale…And that is a massive achievement.”

Indeed it was. The ride was not always smooth. How could it be with Ed Koch at the helm?

One thing was always certain. We knew who was boss. Mayor Koch was so in your face for so long that a whole generation of children grew up thinking “Mayor” was his first name. He relished the good fight and the good quip. Here are a few of his favorites:

“The UN is a monument to hypocrisy.”

“I don’t get ulcers; I give them.”

When he refused to pet a tiger at Madison Square Garden, a bystander yelled, ”Mr. Mayor, a coward?” To which the mayor responded, “No, the mayor is not a coward. And the mayor is not a schmuck.”

Then there are those comments he made to Playboy magazine just as he was starting the 1982 campaign for governor. Koch called them “the dumbest he ever made.” There’s no argument here, considering some of what he said: “Living in rural areas is a joke.” “Have you ever lived in the suburbs? It’s sterile. It’s numb. It’s wasting your life” And he talked about wasting time in a pickup truck when you have to drive 20 miles to buy a gingham dress or a Sears Roebuck suit. To top it off, he said, “Living in Albany would be a fate worse than death.”

On Election Day, he was spared that fate.

The time is right for a second look at those years.

CONFRONTING DESPAIR

Pete Hamill: When Ed Koch took office on the first of January 1978 there were neither parades, rallies, preparations for bonfires nor any sense of celebration. The fact was that we had gone through such a terrible time there was no reason to celebrate.

It’s hard to imagine now what faced Ed Koch when he walked into City Hall. In the fall of ’75, the fiscal crisis erupted. There were layoffs: cops, firemen, sanitationmen, teachers, librarians. At the same time, there was a kind of nexus – a gathering together – of three factors: youth, drugs and guns bringing a sense of menace to our city that simply wasn’t there before.

Crime was growing. But the dailiness of our lives was even worse. Bags of garbage opening in the streets. The South Bronx and Brownsville were burning. The homeless suddenly appeared among us. They were not black or white or Latino. They were everyone. Some of them had been displaced by the burning of the South Bronx and had lost their places to live. Some of them were drug addicts, some of them were alcoholics, some of them were lost souls who have been in this city since the time of the Dutch. The shopping bag lady became a symbol of New York. Not a criminal, but just another lost soul wandering around with all her possessions.

At the same time, a guy named David Berkowitz, better known as the Son of Sam, was roaming the streets. His miniature psychopathic crime wave started in July of ’76 and didn’t end until August of ’77.

And along came Koch. At the beginning, no one gave him a chance. He was the classic Greenwich Village liberal. He had gone to the South to march for civil rights. He opposed the war in Vietnam. He was the object of all the stereotyping that goes along with a place like the Village. And he started running. Nobody paid much attention. Later, a new player in town named Rupert Murdoch decided that Ed Koch was his man and gave him a little more ink than he was getting anywhere else.

Then on July 13, we had a power failure. Twenty-five hours. Fires broke out, there was looting of some of the worst junk in the Western hemisphere. Paintings on velvet. The worst looking television sets available anywhere in the United States. Crappy little toys. The police, undermanned as they were, made 3,776 arrests.

The sense of despair among many New Yorkers was genuine. A lot of my friends said, “I’m leaving." Some of them committed a form of suicide and moved to New Jersey. Others went to Florida and, God help us all, California. It wasn’t simply a matter of us losing their tax money. We lost the thing that they were – New Yorkers.

Along came Koch. And in the first month, we suddenly started paying attention in a way we had not during the election. Here was a mayor who was a combination of a Lindy’s waiter, a Coney Island barker, a Catskill comedian, an irritated school principal and an eccentric uncle.

He talked tough and the reason was, he was tough. He was in combat during World War II as an infantryman. He was awarded two battle stars and came home a sergeant in 1946. He didn’t profit from the war like so many. He fought it.

That toughness was key to what I began to think of -- and I’m sure everyone else did -- as “the act.” He also was very wise and intelligent about the way he approached his job. He knew he couldn’t govern in the traditional sense because of the fiscal crisis. The power had fallen to Hugh Carey, Felix Rohatyn, the Municipal Assistance Corporation board, faceless bankers. But while Koch couldn’t govern traditionally, he could entertain us. In a way, that was better.

He came at us with a sort of scorn for weakness and self-pity. All sins were permissible in New York except self-pity. Admittedly, he could be ugly in conversations. But most of the time he made you laugh out loud. And it worked. It worked because he knew the problem in New York was not crime. It was morale.

And he went at it with a sense of joy, a sense of combat, a sense that made us all know “that’s the voice of New York, that’s what we are.”

There was something touching about him too. When the lights went out and the rallies were over, there was a sense of loneliness in Koch -– something that made him more human. Then you think about what happened in the third term when so many people he trusted betrayed him, and his sense of isolation grew. He should not have had to go through that.

The press failed him too. We were covering candidates and not paying attention to all those little offices where Bartleby the Scrivener sat in the corner.

I always think of him now with an enormous affection. He was a huge pain in the ass, but he was our pain in the ass, and we’re lucky to have had him.

THE FINANCIAL MESS

Stephen Berger: Once upon a time, the state legislature was controlled by upstaters and the city had wealth. We were actually exporting revenue into the state.

We also had continuing waves of immigration. So we had very strong social programs in the state. If you look back, you see that a historic deal was openly cut. We live with it today. You see it with Medicaid and welfare programs. It’s basically a deal that said, that unlike any other state in the United States, in New York the local government –- in this case New York City -– would pay half of the state’s cost of many of these social programs.

The second piece is that Albany was not just 150 miles away from New York City. What we learned during the fiscal crisis was that neither the city nor the state really understood that they were two black boxes held together with a piece of string. They didn’t understand how we worked, we didn’t understand how the state government worked and there was a total breakdown in communication between the state and the city.

Third, New York City’s commitment to social programs came with an arrogance and a self-righteousness, which overlooked the range and scope of programs, that a state with full taxing power would have had trouble maintaining.

There were many warnings of the fiscal crisis. New York City raised taxes 15 times [during the 1960s and 1970s]. We were constantly outspending our budget. The city spent all its reserves. The city raided its capital budget, robbing its future to pay for its present

From the mid 1960s to the early 1970s, there were public commissions, city commissions warning of the coming crisis. It would take every dollar of personal income inside New York City to find that money. By 1975 –- this was how broke the city was in 1975 -- it had effectively borrowed every dollar it was going to raise in local revenue for the next year. You start January 1, and you’ve already spent more than you’re going to take in the next year. Now that’s exactly where we were. It was $7 billion. Even in today’s terms, $7 billion is a fair amount of money.

Finally, the lenders said, “we’ve had enough.”

From 1976 to 1977, the [financial] control process was put in place. It stabilized the situation and created a new financing structure.

But for the city to restore itself and return to self-government, it had to show it could run itself efficiently and effectively, balance its budget, year in and year out. The revenues had to match the expenditures. The city had to keep it balanced and then persuade the lenders.

No one was better prepared to take over than Ed Koch. In part that was because he was an observer at the Financial Control Board. He was not an outsider. He had an understanding of the problems. So, he knew why he had to balance the budget. He had to manage the city. He had to persuade the workforce to do more with less. He had to rein in spending for the poor. He had to persuade the lenders to believe in us again.

He brought the energy and the discipline that remain today and are the basis of the confidence that people have in the city. Unlike his predecessors, he would balance the books.

RACE RELATIONS – AND LAUNCHING AL SHARPTON

Al Sharpton: Part of the thing that was most refreshing and most appalling about Koch is that he will stand for what he believes in. He will not say what you want him to. And he will not be intimidated either way.

He always was a bit of a showman and was a good politician in terms of being able to convince people. He has my daughter convinced that the only reason he was the first to arrest me was to launch my career.

It was on April 4, 1978, which was the anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King... We arranged a meeting with the mayor. The fact that he would even see four unknown ministers showed that he was more open than we gave him credit for.

We wanted to demand that the federal government replace the cuts in summer jobs for youth that summer. And Ed Koch, unlike many liberals at the time, looked at me and said, “No, and I’ll tell you why.” And I said, “What do you mean no?” He says, “No. I’m not going to do that.” And I said, “Well if you don’t, we’re not going to leave your office.” And he said, “Let me explain to you why your approach is wrong.”

He had a job to manage the city and I think that, even if he felt our core reason was right, he felt he had to have an administration that would appear to not deal with [those who did not] stay within certain boundaries of the law. So, after he lectured us for an hour that the federal government had fiscal problems, the city had fiscal problems, that of course he wanted young people to be working and our approach was not the best approach to get him to do it, he asked the police to come in and remove us. I remember the young man who was standing in uniform with handcuffs. And he said, “Well, we need a complainant.” Koch says, “I am. Arrest them. I’ll sign the complaint.” And we were carted out on the stairs of City Hall. It was the first time I was arrested, and some 20 some years later at my birthday, he reminded me that no one had heard of Al Sharpton until then.

I invited him to my birthday. About 2,000 people were there -- mostly African Americans. He and I had been working together on the Second Chance program. I didn’t know how these Harlem people were going to respond. And he came on stage and everybody stood and started clapping. He walked to the microphone, and he looked at the crowd and said, “Do you miss me?” Well, after Giuliani we really did miss you.

At the end of the day, he had respect for African Americans and Latinos. He respects us enough not to placate us. We probably would have liked it better if he told us what we wanted to hear. But he respected us enough to talk to us like adults and tell us what he was and wasn’t going to do. And as I got older I learned to respect people more that didn’t give me empty promises just to get me out of their office. When he said yes, I could go and say he would keep that yes and when he said no he meant no. Even when I thought he was wrong, I never felt he was disingenuous.

Michael Goodwin: Could you elaborate more on racial tensions and his effect on race relations.

Al Sharpton: Well I think the tensions were national and that the mayor inherited a lot of things in the African-American and Latino community that were happening then.

His personality became an easy target because he was so in your face. I think it was not so much his stand on the issues as his style that caused confrontation at the time.

Race relations because of Howard Beach and Bensonhurst and other incidents became very, very bad. The legacy of those years was that we did get through. What no one talks about is that New York had no riots like South Central or Watts. One of the reasons I think is because we dealt with it openly, and we dealt with it squarely. The lasting situation in the city is that we talk about the issues. I don’t think we’re anywhere near racial harmony, but there is more racial sensitivity than there was.

Koch steered the ship through some very turbulent waters...

THE MAYOR AND THE MEDIA

Ken Auletta: When Koch ran for mayor in 1977, he believed that the city government and the city administration were much too compromised. He believed that special interests ran the city. And he spoke words sharply, and the press loved hearing that.

And he had this way, as Reverend Sharpton said, of standing up to people and not trying to placate them. That married very well with the press’ interest in conflict. And it also married very well with the mood in the city at that time.

Then what happened –- the secondary thing –- is that Rupert Murdoch stepped in and not only endorsed Ed Koch -– the New York Daily News endorsed Ed Koch, the Times endorsed Mario Cuomo -– but Murdoch not only turned his editorial pages over to Ed Koch, he turned his front page over to Ed Koch.

As a congressman, Koch did not fill a room. We knew he was smart. We knew he was outspoken. But when he ran for mayor, Ed Koch was transformed. He became what we call a personality. And I think he filled that room.

In 1978, he starts giving press conferences and so he met the second bias of the press: to be entertaining. He gave great sound bites. And the TV press played that up. He was very charming for a long period of time, just asking that question, “How am I doing?” But after a while, particularly with the media, it begins to wear thin.

And, as Pete said, it may have caused problems because we tended to focus on the personality of the mayor and to ignore the government. And in truth, there a second question he should have been asking which was, “Hi, how’s my government doing?”

By his third term, that second question became predominant. If you look back on his three terms, you see he performed in a way that no mayor had since La Guardia. As Pete eloquently said, he gave us back our morale, but he gave us back our self-government too.

THE RIGHTWARD SHIFT

Joyce Purnick: I know I’m getting old when I hear Reverend Al Sharpton speak in laudatory terms of Ed Koch.

I will try to summarize a half-century of Ed Koch’s political evolution in five minutes. He was a Greenwich Village liberal who moved to the center -– some say to the right –- as he saw more and experienced more of government. There is no doubt that Koch’s evolution was a reflection of what was going on in our society, particularly among many Jews. There was a souring of the traditional alliance between Jews and blacks partly because of the changes in the city during John Lindsay’s years, with middle class anger over Forest Hills and Ocean Hill-Brownsville (in PDF format).

I will try to summarize a half-century of Ed Koch’s political evolution in five minutes. He was a Greenwich Village liberal who moved to the center -– some say to the right –- as he saw more and experienced more of government. There is no doubt that Koch’s evolution was a reflection of what was going on in our society, particularly among many Jews. There was a souring of the traditional alliance between Jews and blacks partly because of the changes in the city during John Lindsay’s years, with middle class anger over Forest Hills and Ocean Hill-Brownsville (in PDF format).

I’m not convinced Koch was ever quite the classic Village/West Side liberal that some people thought he was. I don’t think his focus in his liberal youth was as much ideological as it was tactical.

In any event, by the time he ran for mayor he was taking on the teachers union. He won the primary in large part because he ran in the center -– to the right -- and in large part because of his temperament, his candor -- not his sense of humor because Ed Garth kept that under wraps in 1977.

I think that it’s fair to say that Ed Koch wasn’t as revolutionarily a centrist as he might have wanted to be. But there were the unions. There was the Board of Estimate to deal with, the state legislature to get legislation through. You can’t be fighting with everyone all the time.

The inclination was to govern more as Rudy Giuliani did eventually. Even Giuliani didn’t stray as far from the traditional as he would like us and the rest of the country to believe. If Koch wanted to govern that way, I don’t think he really could have. There were realities to deal with. And, as we all know, he couldn’t keep fighting the party leaders. Instead Koch made alliances with those leaders.

He said he did so to govern, to get legislation through Albany. And I’m sure that is part of it. But I think in part it was also his ego. By making those relationships, Koch signaled his acceptance of those leaders and the way they functioned. Inadvertently that led to corruption scandals of his third term.

Now not even Koch’s harshest critics have ever accused him of personal corruption. The problem was two-fold. The bad guys thought they could get away with it. The other problem was Koch’s naivetĂ©. What else could explain his kissing Donald Manes on the forehead after Manes' attempted suicide?

I remember when Koch turned against Manes and called him a crook. At the time, Ed Koch seemed shocked. I don’t think the pattern of corruption seemed possible to him. I don’t think he understood that doling out low-level patronage in City Hall’s basement could have led to corruption. I don’t think he realized it sent out a message to those intent on abusing the system.

I do not think that the corruption scandal will be anywhere near the center of Koch’s place in history. I think it will be overshadowed by two pieces of his legacy. One, as we have discussed, getting the city back on track after the fiscal crisis with the kind of spirit and energy that the city needed and which the entire world would know. The transit strike. The “how am I doing?” stuff. The unstoppable ego. He loved to talk to us about the city and we loved to listen.

Secondly, I think that Koch was a harbinger of a major change in the way we govern large cities. He began the change from the old coalition of labor, liberals, minorities and the clubhouse that has since taken us through Giuliani and to Bloomberg. It’s popular today to credit Giuliani with changing of the city’s politics as usual, but I think that began with Koch. He took it as far as he and his roots would let him. Giuliani broke the rules, Bloomberg ignores them, and Koch wrote his own rules with his personality and his spirit and with his love of politics.

LABOR RELATIONS

Victor Gotbaum: It’s really an oxymoron for me to be up here praising Ed Koch. He was tough. He didn’t discriminate when he took office –- he zinged everybody he thought didn’t fully do the job of helping New York City.

And I must say that, at the beginning, I didn’t dislike Ed Koch. I despised him.

A woman I know [Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum] – I happen to be married to her – said, “The reason you don’t like him is because you and he are so alike.” I didn’t talk to her for at least six minutes.

An interesting aspect of Koch is that his enemies made him. The 1980 transit strike. Any labor leader knows that you can’t win the hearts of the public if you go on strike. You may have to do it if workers are really repressed, but in the mainstream you take a terrible, terrible beating. It was the ’80 strike that really made Ed Koch. He took a strong stand. He walked across the bridge as you all recall. Labor might have hated him for it, but he knew exactly what he was doing.

[In another case,] he wanted 35 layoffs, and I opposed him. I knew that if I took him head on, it would be a bad mistake. So I negotiated with him on changing the titles where they would do work and get federal money. He listened and then I discovered something about him: He could negotiate and he would negotiate.

The only reason Koch and I get along at all is that Betsy liked him. She mentioned two things: that Ed Koch didn’t represent the city, he was a piece of the city. He was a part of the city. You couldn’t divorce Ed Koch from the city.

Another aspect of him – and I was trying to think of another word – but he was pure schmaltz. I mean that in a positive sense. He was so much a part of the city that he could get away with it. He would do things that other mayors couldn’t do.

It was his brashness, his moving forward, and his feeling, his strength that he was doing the right thing for this city. So you could negotiate with him, be angry at him, but he would never, never hurt the city that he loved so much.

RANKING KOCH

Michael Goodwin: Of all the New York City mayors of the 20th and 21st centuries, where would you rank Ed Koch?

Pete Hamill: Second or third after La Guardia. If you had to write a novel about a New York City mayor, you’d rather write about Koch than Robert Wagner, and Abe Beame would be like writing about a turnip or something. But I think the three would be La Guardia, Koch and Giuliani – the first term. Not the second term.

Stephen Berger: I would focus more on the first two terms where Ed was an architect and an engineer. He was a cheerleader. And he not only put stuff together but put them together in a way that it’s held up by and large now for 35 years. That’s got to put him right up there.

Joyce Purnick: That sounds right to me. Everyone puts La Guardia at the top. Bloomberg has accomplished a lot of what Giuliani claimed to have accomplished.

Ken Auletta: It depends upon whether you count Bob Moses as a mayor – then you have to assess whether his influence was good or bad. But I think Ed Koch is up there with La Guardia.

It reminds when I said to Hugh Carey, “You know you’re probably going to go down as probably the third best governor in this century.” And he said, “Really? Who are the other two?”

WHAT WENT WRONG?

Michael Goodwin: How would you describe Ed Koch’s greatest failures?

Michael Goodwin: How would you describe Ed Koch’s greatest failures?

Pete Hamill: He didn’t pay enough attention to Bob Dylan in "Subterranean Homesick Blues," particularly the line, “Don’t follow leaders, watch the parking meters.” In many ways it’s admirable that he did not see people as potential felons. But he trusted some people who betrayed his faith. That’s nothing to be ashamed of.

Stephen Berger: We never had a mayor who had more potential to do what should be done in the state. This is to take all the cities and all the counties –- all the local governments –- and lead them against a state bureaucracy, a state government, which is clueless about local government. He had the political skills and the political instinct to put that kind of coalition together. The problem is you have to go north of the city to do that. I think if Ed had done that he could have made a difference.

Every one of those guys throughout the state, whether you’re in Erie County or the mayor of Syracuse, has some of the same problems that the City of New York has. I think being in a real coalition with those guys could have made a real improvement.

Joyce Purnick: Hubris. If you take it down a few pegs you don’t have Ed Koch, so it’s double edged, but maybe half a peg.

Ken Auletta: If you go back to Greek mythology that virtue is also a vice, then if you review Ed Koch’s vices, narcissism, his preoccupation with himself and being on stage, you also remove some of his virtues. I think the good comes with the bad and the bad with the good.

Michael Goodwin: Victor, if you could change one thing, what would you change about Koch?

Victor Gotbaum: I wouldn’t let him get elected.

WHAT KOCH DID NOT DO

Audience member: There were failures in his administration in my opinion. He let the public schools deteriorate, Westway was never built, race relations did not improve, and for the buildings along the Cross Bronx Expressway that had been decimated, [his] solution was to put up decals.

Michael Goodwin: There were many problems that did not get solved. He tried to focus on some of them. Education obviously was a big one. Interestingly, I think we’re now looking at education as a key issue just as crime was a key issue in the previous eight years.

So you have a kind of changing of the guard of ideas that are considered prime topics. With Mayor Koch, obviously finances were the first problem. You have a limit to what you can achieve.

Stephen Berger: You have to be able to focus on a few things if you want to be successful. You cannot do 20 things and do them well. What works is what the mayor or chief executive decides is going to work.

“New York Comes Back: Ed Koch and the City” is on display at the Museum of the City of New York through March 26, 2006.

Â

Rising Heating Costs

This year New Yorkers will face sharp rises in home heating costs, and while there is some government assistance available to individuals of low income, it is likely that the great majority of those eligible will never receive it.

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita significantly damaged oil-refining capacity in the Gulf Coast, and oil prices climbed to more than $70 a barrel in late August. What this means for the average New Yorker who uses home heating oil, according to Senator Charles Schumer, is an increase of some $450 in heating costs over last year.

Many New Yorkers use natural gas to heat their homes, and the major hub for transporting natural gas to the Northeast is also located in the Gulf Coast region -- which is why the average New Yorker using natural gas will see a price rise that is even higher, at some $473.

Federal Efforts To Reduce Heating Costs

Northeastern senators of both parties have called upon the Department of Energy to release heating oil from the Northeast Heating Oil Reserve . President Bill Clinton established the reserve in 2000 in order “to reduce the risks presented by home heating oil shortages”. As of early November the department has refused this request, arguing that the situation is not serious enough to justify tapping into the reserve.

Another idea that has gained the support of Democrats as well as typically tax-averse Republicans, is to impose a "windfall tax" on oil companies . All of the major companies posted record profits in the third quarter of 2005, at the same time that many consumers faced record-high gasoline prices. Some proceeds from this tax would help poor and elderly Americans pay their heating bills.

The oil companies argue that their profits are not disproportionate, and that a windfall tax would reduce their incentive to locate new sources of energy. They have a powerful ally in President George W. Bush, who is opposed to the idea.

Individual Assistance With Heating Bills

Regardless of how the political skirmishes are resolved, the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) will help individuals pay their heating bills. This is the primary federal program for this purpose, and it took effect in New York State on November 1, 2005, though it is not yet clear how much money will be available. (For fiscal year 2005, New York State received $235.6 million in such funds.)

In New York City, these funds are administered by the city's Human Resources Administration. Individuals can receive assistance whether they pay their heating costs directly or if these costs are included in their rent. Eligibility is based on an individual or family’s monthly income, and the program provides both regular and emergency benefits of up to $400 a year. The city estimates that it provides almost 440,000 grants each year, for a total of about $31 million.

The National Fuel Funds Network, an umbrella group for 250 organizations nationwide (including in New York City, the HeartShare Neighborhood Heating Fund) that raise donations to help people with their heating costs, estimate that only 15 percent of individuals eligible for the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program actually receive assistance. Marcus Banks is a librarian at the New York University School of Medicine.Â

What Now, Mayor Bloomberg?

"All I wanted -- and you gave it to me -- was four more years," Mayor Michael Bloomberg said on election night.

But in his reelection campaign, Bloomberg focused on the past, not the future, boasting of his record during his first term, but avoiding until the last few weeks his agenda for his second term.

Mayor Bloomberg's plans for the next four years -- which are outlined in a document on his Web site entitled, "Moving Forward: The Bloomberg Vision for New York City" -- are notable, not only for what they promise, but for what it will take to accomplish them. They depend largely on the mayor's ability -- not much tested in his first term -- to win battles outside of the city.

On education, the mayor wants to double the number of pre-kindergarten and day care slots to serve more than 300,000 children. Key to the plan, however, is funding from the Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit and the $23 billion the court has ruled the city schools are owed in education funding. The mayor has said that the governor and State Legislature in Albany must contribute the full amount and that the city should not pay a cent. Governor George Pataki is appealing the court ruling.

On housing, the mayor recently expanded his previous housing plan and promises to build or preserve 165,000 affordable homes by 2013. His plan, however, depends on the continued strength of the real estate market, developers willing to work with the city, and hundreds of millions of dollars in financing from philanthropic and financial partners. And for every new affordable apartment built, the city loses others as rent-stabilized apartments drop out of the state-controlled system. One of the reasons the city has such a housing crisis, some experts say, is that lawmakers in Washington have slashed federal housing subsidies.

On crime, Bloomberg focuses on strengthening state gun laws and securing more homeland security funds from the federal government. He is also calling for the governors of New York and New Jersey to create new seats on the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and Port Authority for the city police commissioner to help the city plan for future terrorist attacks.

On economic development, the mayor is banking on the rebuilding of Ground Zero, a site still mired in controversy, owned by the Port Authority, and leased by private developer Larry Silverstein. When Bloomberg recently called for more housing to be built in lower Manhattan, he was roundly criticized by nearly everyone involved including Governor Pataki, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, who represents the area, and the two U.S. Senators from New York, whose job it is to lobby for federal rebuilding money.

And the mayor's second term agenda is also notable for what it does not say: how he plans to address the looming $4.6 billion budget deficit. The only tax the mayor and the City Council can raise without permission from the governor and State Legislature is the property tax, which was already hiked by 18.5 percent in 2002. And Bloomberg has declared budget items like debt payments, labor pensions, and funding for Medicaid as "uncontrollable," meaning he can do little to change a third of the city budget.

The mayor proved he was capable of big victories in Albany when he convinced the State Legislature to give him control of the schools. Beyond that, many of the mayor's most significant accomplishments happened "in house." He used his knowledge of technology to create the 311-call system. He lobbied the City Council to pass his smoking ban in bars and restaurants. He successfully negotiated contracts with city workers. But he avoided battles - like taking a more active role in Ground Zero or pushing for a commuter tax - knowing that the power of City Hall only extends so far.

The mayor, who has touted himself as a non-partisan, apolitical manager of the city in his first term, may ultimately be measured by how successful a politician he can be in convincing people in Albany, Washington, and elsewhere to help him achieve his vision for New York City.

Mark Berkey-Gerard, city government editor of Gotham Gazette, was in charge of campaign coverageÂ

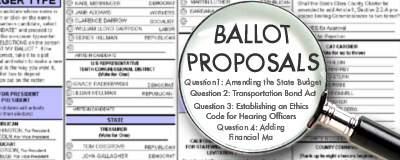

The Ballot Questions

| For more details on these ballot questions -- essays arguing pro and con, transcripts of debates -- click on The Fine Print on the Ballot. |

When New Yorkers go to the polls on November 8th, many will be surprised to find that — in addition to being able to choosing the city’s mayor --- they can vote on four ballot questions – two statewide and two for New York City alone. Here is a quick rundown of the measures:

Question 1: Amending the State Budget Process

This measure would amend the state constitution and would enact several pieces of legislation, already approved by the legislature, concerning the way the statewide budget is formed. It calls for the creation of a contingency budget, which would automatically go into effect if the governor and the legislature do not agree on a budget by the beginning of the fiscal year. That contingency budget – based on the previous year’s budget – would provide the basis of the new budget. Under this scenario, legislatures would have greater power to shape the budget than they do now and than they would if they agreed to a budget earlier in the year -- without the contingency budget. Other provisions of the ballot measure would establish an Independent Budget Office whose members are appointed by the legislature, and move certain items onto the general budget that are currently funded independently. (Read an overview by the Rockefeller Institute in .PDF format)

Proponents (in .PDF format) say the amendment will bring accountability and transparency to the state's budget process. The specter of a contingency budget, they say, will encourage on-time budgets, while shifting some power from the governor to the legislature would bring New York into line with most other states.

Opponents argue that, because lawmakers will have more power over the budget once the contingency budget is in effect, there is an incentive for them to stall. After the beginning of the fiscal year, critics say, the governor would have practically no power over the legislature, which they think will lead to irresponsible spending.

Question 2: Transportation Bond Act

This state measure establishes a $2.9 billion transportation bond issue – in other words, it calls for New York State to borrow $2.9 billion for various transportation projects. Voter rejected a similar measure in 2000. Half would go to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority to help fund the construction of such mammoth projects as the Second Avenue subway, extension of the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central Station and new buses and cars for subway and commuter rail lines. The rest would go toward road and bridge projects around the state including some in the city.

Governor George Pataki and Mayor Michael Bloomberg back the measure, as do a range of organizations including the Straphangers Campaign, which argues the MTA needs money, and the New York Building Congress, which sees such borrowing as a necessary investment in the future. Opponents, such as the Citizens Budget Commission (in .PDF format), argue that the state is already burdened with too much debt, while E.J. McMahon, director of the Empire Center for New York State Policy within the Manhattan Institute, has argued the measure includes too many ”amenities” along with essential projects.

Question 3: Establishing an Ethics Code for Hearing Officers (in .PDF format)

This measure would amend the City Charter by having the mayor establish a code of ethics for administrative hearing officers, who resolve citizen complaints and adjudicate a range of non-criminal matters, such as parking tickets, noise complaints and building code violations.

The lack of a code of conduct governing hearings is “a matter of special concern” because many people who appear before them do not have lawyers and are not familiar with city rules, Ettina Plevan, president of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, 2005 told (in .PDF format) the charter revision commission in March.

The measure has attracted little attention. Assemblymember Richard Gottfried has said he opposes it because it would shift power from the City Council to the mayor. Others question why such an arcane matter should go before voters. ''Charter revision commissions should be used to meet serious challenges to the city's constitution, not to advance the mayor's politics,'' said Council Speaker Gifford Miller, who backed a measure on class size that was kept off the ballot because of Questions 3 and 4.

But Ester Fuchs, the Bloomberg adviser who heads the charter panel, said in July that an ethics code for administrative judges and hearing officers merits a referendum because of the gravity of the issue.

Question 4: Adding Financial Management Requirements (in .PDF format) to the City Charter

Under this measure, the city would be required to balance its budget by generally accepted accounting principles and ensure that the annual audit of the city's accounts also follows such principles. The city would have to create a four-year financial plan, as well as keep a minimum general reserve of $100 million. It would also be restricted in its use of short-term debt.

The city is already compelled to do these things by the Financial Control Board, which is set to lose much of its power in 2008.

Proponents of the measure say that the charter revisions would guarantee that the city would continue to act responsibly after the board's expiration.

Those arguing against the revisions say that they do not adequately replace the board's requirements. Without a specific, independent entity to assess whether the city is fulfilling its responsibilities, they argue, there is no way to keep city officials honest. Â

The Fine Print on the Ballot

An Overview of the Four Ballot Questions

A guide to all four questions on the November ballot.

More...

Question 1: Amending the State Budget Process

Should the state budget process be amended to give more power to the State Legislature?

-Overview of Question 1

-Transcript of a forum on Question 1

-Vote Yes by Megan Quattlebaum and Blair Horner

-Vote No by Gerald Benjamin and Charles Brecher

Question 2: The Transportation Bond Act

Should the state borrow $2.9 billion to fund mass transit and road improvements?

- Overview by Bruce Schaller

- Vote Yes by Jeremy Soffin

- Vote No by Nicole Gelinas

Question 3: Ethics Code for Hearing Officers

Should the mayor create an ethics code for administrative judges?

-Overview by Joshua Brustein

-Vote Yes by Peter J. Kiernan

-Vote No by Richard N. Gottfried

Question 4: Adding financial management requirements to the City Charter.

Should the city add fiscal controls to the City Charter to ensure a balanced budget?

-Overview of Question 4

-The Fiscal Crisis After 30 Years by Joshua Brustein

Â

Transcript of Final 2005 General Election Mayoral Debate

Transcript of Final 2005 General Election Mayoral Debate

On November 1, 2005, the New York City Campaign Finance Board and WNBC played host to a final debate with mayoral candidates Michael Bloomberg and Fernando Ferrer. It was moderated by Gabe Pressman. Questions were asked by reporters Melissa Russo, Jay DeDapper, David Ushery, and Jorge Ramos. The following is a transcript of the debate.

CAMPAIGN ADS

Melissa Russo: Mr. Mayor, as a Republican in a city of Democrats you like to say that you are a non-partisan kind of guy, that there is no Republican or Democratic way to pick up the garbage. But you have also contributed millions of dollars to Republicans even though you admit that some of their policies are out of step with, and even harmful in some cases, to New York City - most recently the sweeping protection for the gun industry. This political tightrope subjects you to criticism like the following cartoon released yesterday by your opponent. [A clip of the Ferrer campaign ad depicting Michael Bloomberg riding a horse with George W. Bush plays].

Mr. Mayor, is this ad really unfair and disgusting as your campaign called it or are you trying to have it both ways at a time when this country is bitterly divided along partisan lines?

Michael Bloomberg: Melissa, I don't know that comic books are very important in this election. We should be talking about real issues. Most of the money that I have given was to the same organization that the New York Times did, a non-profit organization that was set up to finance the convention that came to this town. We would have done the same thing for the Democrats. What I've tried to do with my own money is try to give money to people who I think can help New York, whether it is Washington, Albany or in New York City. But this is really about getting the schools better, this is really about improving social services, this is really about making this city safer. As you said yourself, there is no partisan ways to do that. We have to deal with everybody and we are going to try to get help from everybody.

Melissa Russo: Do you believe that ad is disgusting as your campaign is quoted as saying in today's paper?

Bloomberg: That is the first time I've seen the ad. I saw about two seconds earlier today. I didn't see the whole thing.

Melissa Russo: Why not just admit that you a Republican by label only if that is what you want New Yorkers to believe?

Bloomberg: I don't know that I want them to believe that. I believe in some things in the Republican Party. I believe in some things in the Democratic Party. The Republican Party gave me an opportunity that the Democratic Party would not give me. It was a chance to change this city. It is a chance to leave a better world for my kids. And I took advantage of it.

Melissa Russo Mr. Ferrer, do you really expect New Yorkers to believe that Mayor Bloomberg is a right-wing Republican after four years in office serving New York City? And isn't it a good thing to maintain close ties with both parties if you are a mayor trying to get things done?

Fernando Ferrer:Ah, come on. I don't think there is anybody in America who honest to God believes that a $7.5 million contribution to the Republican National Convention is non-partisan. Or being one of the largest donors to George Bush and his party. It is a party that has promoted policies that have hurt this city. It is anti-choice, anti-gun control, and pro privatizing social security.

Melissa Russo:But has Mayor Bloomberg really governed as a conservative Republican in your opinion?

Ferrer:Look, you can't disclaim for the policies while you are opening your checkbook wide. My grandmother had a saying about all this. In English, it is "tell me who you walk with and I will tell you who you are." Mike in two languages you are a Republican.

Melissa Russo: Is that true? Are you a Republican?

Bloomberg:Well I did give $2,000 to George Bush. I gave more than that to Bill Clinton when he was running. I try to do what is right. And I am going to continue to do that. If someone can help us, I am going to continue giving them the money.

Melissa Russo: Mr. Ferrer, we would like you to respond to a new ad from the Bloomberg campaign. [A clip of an ad calling Ferrer a "flip-flopper" plays.] Is that true, Mr. Ferrer? Do you flip-flop?

Ferrer: Sounds to me like an ad that George Bush ran against John Kerry. Look, people who know who I am after 20 years of elected public office. They know this about me. There is only one principle that has ever guided any decision I have ever made. That is this - that every New Yorker who works hard and does right should get the tools they need to build a better life here in this city.

Melissa Russo: Mayor, do agree?

Bloomberg: I think everybody knows what my opponent stands for. He stands for complaining. He stands for identifying problems and never coming up with solutions. And that is different than governing. It is easy to be a critic. It is very hard to lead. The city is going in the right direction. And I think the policies that we have had for the last four years are the policies we should continue.

WAR IN IRAQ

Gabe Pressman: We should move on to another subject. As I have visited neighborhoods across the city I have found that Iraq is uppermost in the minds of many voters. My question to both of you is: Do you think the next mayor should use his office as a bully pulpit to try to influence the federal government's policies on Iraq?

Ferrer: You bet I do. Mike Bloomberg has said previously he didn't think the war in Iraq was a local issue. Explain that to 37 families who lost soliders fighting in Iraq. Explain that to people who watch us build firehouses in Iraq while we are shutting them down in New York. Or spending billions of dollars to promote that war instead of doing the things we need to do to promote decent and affordable housing, good schools, or health care.

Gabe Pressman: What would you advocate for the president?

Ferrer: I would advocate for the president to get our troops out of there as promptly as possible. Look, they are still looking for weapons of mass destruction. And tell you the truth, it's a war that has cost too much in terms of human life and in terms of our national wealth, and the distortion of our national priorities.

Gabe Pressman: Mr. Mayor, do you agree with him that the war should be brought to an end as soon as possible?

Bloomberg: Let's see why we are here, Gabe. There was a point where intelligence reported that there were weapons of mass destruction in Iraq that could have threatened our country and destabilized the world. The Senate, our two senators, Senators Schumer and Clinton, the President, most of Congress thought that we should go in and get rid of those weapons of mass destruction. It turned out that there was a massive intelligence failure. But you are there. And now we have lost over 2,000 of our men and women, 37 from New York City. Walking away that this point would make all of them to die in vain. It would be an outrage. What we have to do is stay there until the generals say that Iraq's government can maintain peace and maintain a democracy. And in the meantime, we should continue to support our troops so that can continue to protect themselves and continue to carry out the mission that we have asked them to do. Nobody is happy to be there.

Gabe Pressman: Do you think we were mislead into that war?

Bloomberg: I think there is no question that there was a catastrophic failure of the intelligence community.

Gabe Pressman: Mr. Ferrer, don't the men and women from New York serving there deserve to have their commander-and-chief respected while they are there?

Ferrer: Of course they have every right and expectation to have the full support of the American people - for themselves, for their bravery, for their sacrifices. For those 2,000 who made that supreme sacrifice. But that doesn't make that war correct. It doesn't make the predicate for that war true.

SECURITY IN NEW YORK CITY

Jay DeDapper: I want to direct us back to New York City for a minute to security and terrorism. You two have complained along with every other New York politician that the amount of money that we get from Washington in homeland security funding. Police Commissioner Ray Kelly said a few weeks ago, "This city isn't getting its fair share of homeland security money and I think we have to continue to push the effort." So Mr. Bloomberg, what would you do differently if get the money? What aren't we doing now that we could do if we got this money?

Bloomberg: Ray Kelly is talking about security money. This city does not get its fair share from Washington, the state doesn't. If we had more money, it would, number one, allow us to do other things. But what I have said is that we are going to provide the security we need regardless of the cost. And then I am going to go and find a ways to pay for it.

Jay DeDapper: What are the other things we could do if we got the extra money?

Bloomberg: We would use it to solve our other budgetary problems. But we have bought every piece of equipment I think is necessary to protect this city. We have a police force of the size I think is necessary to protect this city. We give them the training that is necessary so they can come home safe at night to their families and protect this city. And we are going to continue to do that. And I have never looked at the cost of it when I have made a security decision. But we'd love to get more help from Washington.

Jay DeDapper: Mr. Ferrer, you've said the same thing. You don't think the mayor has done enough getting that money?

Ferrer: It is plain as day that we are not getting homeland security funds based on risk, based on the fact that New York City took it on the chin for the rest of American in the attack on 9/11. But let me give you a specific example of that. Some months ago, at a subway station in Brooklyn, Borough Hall, I put forward a mass transit security plan. The simple fact is that I have criticized this mayor and his four appointees to the MTA board. Not any four appointees, the four high ranking appointees of Mike Bloomberg. And they sat there like potted plants. When they failed to spend $390 million that was allocated to upgrade security in our mass transit system. Recently, they put out a few contracts and they managed to bungle that. Look, those $390 million were absolutely necessary, and not to install, as the mayor put it, "a bunch of cameras," but to train the MTA personnel in anti-terrorism and surveillance techniques, to install surveillance cameras, explosive detection technology, and to improve communication below ground and above ground.

AVIAN FLU

David Ushery:Earlier today, President Bush unveiled a $7.1 billion preparedness plan to confront an outbreak of the bird flu, the avian flu. But given the governments much criticized response to hurricane Katrina, do you have confidence in the federal government's ability to confront this outbreak? Mr. Ferrer, we will start with you. What would you do as mayor to protect the city?

Ferrer: There is no question that we have to lobby them strenuously and vigorously to get the help we need. But in the end, this is a city that must do for itself and leave no one behind. And that is why in every one of our disaster preparedness plans, we have to prepare to such an extent that in a hurricane, we leave no one behind in low-lying areas. In the case of avian flu, to have enough vaccine stockpiled so that we can take care of New Yorkers so that we can preserve life and safety.

David Ushery: The president mentioned earlier the guaranteeing parts of the country, perhaps a city or beyond. Do you think the city should be prepared to do that?

Ferrer: I think the city has to be prepared to fight avian flu, but I'm not ready to go as far as the president has. Of course, I don't think the president has any plans about this. And that is really the tragedy here.

David Ushery: Mr. Bloomberg, do you have confidence in the federal governments ability to protect the city?

Bloomberg: At the moment we don’t know what the risk is. What I am first concerned about is to make sure that this year, for the kinds of flu that around that we get everybody their flu shot. 35,000 Americans will die from flu this year. I am trying to make sure that particularly vulnerable parts of our city, our seniors and our young children, get flu vaccine. In terms of down the road, we have plans. Everybody's got plans. But we don't know if there will be a vaccine available to prevent or to deal with an avian flu that has yet to mutate into something that we've got to worry about. The federal government has shown again and again that they can help, they can give you money, but we have to be prepared locally. That was the lesson of 9/11, that was the lesson of Katrina, you have to be able to handle, at a local level, the problems. Whether it is quarantine, or getting people vaccines, which we are incidentally practicing right now. Using the incentive to get the current flu protection, we are planning we are practicing for the avian flu.

CAMPAIGN FOR FISCAL EQUITY

Jorge Ramos: One of the most pressing issues facing the city is how to improve education and how get the money to do it. The city has been awarded billions in a lawsuit filed by the Campaign for Fiscal Equity. But the state has appealed that decision. A teacher in the Bronx has this question for both candidates.

Teacher in the Bronx: I am a teacher at PS 62 and I would like to know with all of the money that the state of New York owes the city of New York, when are we going to get this money to help our children succeed? When is he going to fight for that?

George Ramos: So Mr. Bloomberg you have had exactly a year to get that money out of Albany. Some say you haven't fought hard enough. So if you are elected, what would you do to get the billions the court say are owed to the city of New York.

Bloomberg: Keep in mind I went and testified before the arbitrator's panel. I went and had our corporation counsel argue in court to get this money. It is now tied up in the courts and when we get the money, I have already put out a plan of how we would spend the $5.5 billion a year that we hope to get. But I haven't waited for that. What I have done is increase city spending on the schools by $2.5 billion. I have raised our school construction budget to $13.5 billion over five years, the biggest in history, splitting it with the state. And when the state didn't come through with the money, the city came up with the money. I am not waiting for CFE money. We have given our teachers a 33 percent raise over the last four years. We've got to educate the kids of today. And when the money comes, we have laid out a plan, first priority will be universal pre-k. But we are not sitting around waiting for it. In the meantime, let's hope the courts continue to rule our way as they have in the past.

George Ramos:Mr. Ferrer, you have said the city must ante up to "prime the pump." If we are entitled to that money, why should we offer to pay?

Ferrer: First of all, I congratulate the mayor on increasing the school budget. But if we still have a 50 percent drop out rate - and I hope we talk about that at some point in this debate - than I would argue that Mike Bloomberg instead of doing more with less, is doing less with more. But let's talk about CFE. I was proud to be an early participant in that action. I was prouder still in the last four years to be a member of its board. They owe us money. They have been cheating the kids of this city - all 1.1 million of them - for years now. I don't think you can approach this as a CEO in a negotiation by putting zero on the table and waiting for them to come up. In fact, the corporation counsel of this city, an appointee of my opponent, who said this city will not spend a nickel. If we have to put up a nickel, no thanks. Well, quite frankly if you listen to the governor, the plaintiffs in this case, and the legislative leaders, they have all said that the city will have to come up with something. I am proud to have come up with a school investment plan that asks a global investment community to invest pennies our children's future.

DROP-OUT RATE

Jay DeDapper: We are going to talk about the drop-out rate. There is a lot of confusion about this: drop-out rate vs. graduation rate. I want to show you want Schools Chancellor said on September 10, 2004. Gabe Pressman asked, "What is the drop-out rate now?" Joel Klein very simply, "In practical terms or in statistics, I mean in real terms, one out of two kids doesn't get a diploma, 50 percent - that's the real world." Mr. Bloomberg, let's settle this once and for all between the two of you. Is the drop-out rate 50 percent as your chancellor said?

Bloomberg: Joel was wrong. He meant to talk about the graduation rate. The graduation rate was 50 percent; it has gone up to 54 percent. In the Bronx, it was 40 percent; it has gone up to 52 percent. But you know, Jay, what has happened here for 20 years is that the elected officials did absolutely nothing for our children. They just said we want to have better schools, but they never came up with any money and they never tried to improve standards. I came into office and said, give me control of the school and I'll make it better, hold me accountable. And when my opponent had the opportunity to do that for 19 years in office, he did nothing. He didn't even talk about graduation rates until all of a sudden he is running for mayor. You can't have it both ways. Everybody knows one child not getting through is one child too many. But we have to do something about it. And that is why we ended social promotion in the third grade, and the fifth grade, and the seventh grade.

Jay DeDapper:Fifty-four percent is something you are not proud of, I assume?

Bloomberg:Fifty-four percent is the number that graduate in four years. A lot more graduate after five, six, and seven years. A lot go on to other schools and are not counted in that number. In four years, 16 percent drop out, 54 percent graduate, and the other 30 percent go on.

Jay DeDapper: Mr. Ferrer, 50 percent? What is it?

Ferrer: Joel Klein is right. Even more than that, Mike, for you to pass the buck for a guy who was out of office for four years, but in office as a councilman and a borough president for nearly 20. I allocated millions to improve technology and school libraries and school construction and security. It’s beneath you. Look, it’s a 50 percent drop out rate. One out of two kids without a diploma, without a future, and without a job. We’ve got to do something about that. And the only way we do something about that is improving teaching and learning in all the grades. Not teaching to a standardized test. But teaching to the highest standards, improving pre-k and after-school programs, music, art, athletic programs, family literacy centers, building new classrooms and new school buildings to relieve the vicious overcrowding that we see in high schools. Schools built for 3,000 students that have 5,000 students.

YEAR AROUND SCHOOL

Gabe Pressman: I’ve got a couple of questions on education requiring short answers. Do you favor, Mr. Ferrer, year around school as a way of developing students who can compete with students from other countries, who have much more intensive educational programs?

Ferrer: Yea, I think the kids who are struggling and need more time on task, extending the school year makes an enormous amount of sense, as does extending the school day and week.

Gabe Pressman: Do you agree with that?

Bloomberg: We are doing it. We have summer school for kids who need more help. And the new teachers’ contract has an extra period, four days a week for the kids who are struggling, every class, every school.

Gabe Pressman: Year around means virtually 12 months with a few vacations in between.

Bloomberg: School with summer-school goes almost year around.

MILITARY RECRUITING IN SCHOOLS

Gabe Pressman: Do you favor, Mr. Mayor, having military recruiters in our schools?

Bloomberg: If we allow businesses to recruit, we should allow the military to recruit. There is nothing wrong with presenting to our high school kids the option of going in the military in the same way that they should have the opportunity to know what jobs they can have.

Gabe Pressman: Short answer, Mr. Ferrer.

Ferrer: No. I want our kids to get jobs. I want them to have the tools they need to be economically self-sufficient. They can make that decision on almost any street corner in this city.

COST OF LIVING

Melissa Russo: Rent, subway fares, taxi cabs, food, the cost of everything in New York City always seems to go up, never down. We are going to hear now from a single mother in lower Manhattan who has a question about affordability.

Woman from Manhattan: How are you going to help the working class in New York City? This is supposed to be a city for everyone, but it is really now just for the rich. And I want to know what are you going to do that I, who live in the city and work in the city, and am a parent in the city, and pay my city taxes, that I can afford to live here? What are you going to do about that?

Melissa Russo: Mr. Ferrer, this woman has a job. She has an apartment. What would you do to make her cost of living go down?

Ferrer: She should be able to live in this city, but increasingly this city is becoming unaffordable to working- and middle-class people. Let’s review some of the facts. The working- and middle-class are being priced out of their own homes. Moderate-income people can’t find a decent place to live that they can afford. That is why I put forth a plan to cut their taxes; not a $400 rebate check on a discretionary basis every year, but a full tax cut, a permanent tax cut. And to give renters tax assistance as well. And to build and maintain the affordability of 167,000 New Yorkers, homes that they can afford.

Melissa Russo: Mr. Bloomberg, is that a good plan? Is that a better plan than you have put forward?

Bloomberg: Mr. Ferrer wants to cut taxes, but he also wants to build affordable housing with tax revenue. So you can’t have it both ways. You have to understand, this is an expensive city. It always has been. And probably always will be. But we have to do is find ways for people to afford to stay here. That is why I fought against the increases in the fares in the MTA. That is why I fought in favor of getting the minimum wage raised. That is why I fought to make sure we are building affordable housing. We have an 86,000 unit program being built with capital dollars and private dollars and we are better than half way there. That is why I want to bring jobs here, because in the end the best answer is a job for everyone.

Melissa Russo: Well, this woman has a job already, she has an apartment. What do you think you will be doing in the next four years if you are elected that will help here?

Bloomberg: We’ve got to keep making this government as efficient as possibly can. We want the services that government provides. We want to keep the cost of those services as low as we possibly can. That is why we have managed to cut $4 billion annually out of the city’s budget and we can do more.

FIGHTING POVERTY

David Ushery: While Melissa’s question focused on the working and middle class, I would like to get some specifics from you gentlemen about New York City’s poorest of the poor. The Bronx is one of the poorest counties in the country, and that didn’t happen overnight. Mr. Ferrer, we’ll start with you because you mentioned your 20 years in elected office as a councilman, as borough president. Did you do enough to combat poverty then? What will you do as mayor?

Ferrer: You mean working with two mayors and scores of community organizations to build 66,000 units of affordable housing? To turn a borough that most people left for dead into a place that President Bill Clinton called a national example for urban renewal? Or you mean working with President Bill Clinton in getting small business programs in the borough to help build 34,000 good jobs for people? No, I’m very proud of that record.

David Ushery: Mr. Bloomberg, let me ask you, a number of experts say that a number of people have slipped into poverty over the last couple of years. You’ve talked a lot about those who have prospered under your reign. Do you have to take some responsibility for those who are not faring as well?

Bloomberg: The numbers show that we are getting 100,000 immigrants from overseas every year. They typically come without formal education, and in many cases with not great command of the English language. And their earnings prospects at the beginning are problematic. That’s why I’ve tried to focus on the kinds of jobs they can get at the beginning -- travel, tourism, restaurants, hotels. Those are the kinds of jobs that we have to bring to this city.

We’ve got to bring construction jobs and open the construction unions up to everybody. And that’s why I’ve negotiated a deal with the construction unions for the first time - a historic deal - where they will open up a big percentage of their apprentice programs to immigrants and to people who have just started to work their ways up the economic ladder. That’s why we have this new women- and minority-owned business program where the city’s business is now being given out to businesses started by people in every community. They’ll get city business and they employ people from their community. That’s why we have to go and build things like the Atlantic Yards, why we have to build the Bronx Terminal Market and why we have to develop Willets Point. Those are the jobs for the future.

NEWSPAPER ENDORSEMENTS

Jorge Ramos: At this time, each of you is invited to ask the other a question. Mr. Bloomberg, you may ask the first question to Mr. Ferrer.

Bloomberg: I guess I’d ask my opponent, the New York Times and Newsday, the Post and the Sun, the Daily News and the Advance, Hoy all endorsed me. Do you think they’re wrong?

Ferrer: Well, Mike, we’ve learned the hard way in the last couple of years that the New York Times doesn’t always get it right. And don’t even get me started on the New York Post. Look, I’m proud of the support I’ve gotten from the neighborhoods and streets of this city. So, if I’m not the candidate of the people in the boardrooms, I’m proud to be the candidate of the kids in the classrooms of this city.

PUBLIC HOSPITALS

Jorge Ramos: Mr. Ferrer, you may ask a question to Mayor Bloomberg.

Ferrer: Sure. Mike, you’ve said in the past that the poor get better health care in this city than the wealthy. Do you honestly believe those words?

Bloomberg: What I was saying is I cannot tell you how proud I am of the progress that our public hospitals - our 11 public hospitals - have made. It is true if you go into those hospitals without any insurance, without any money, you will get the same care as if you can come in and pay for your services. And that care is the best medicine available anyplace in the world today. Thirty thousand people work in those hospitals and they have transformed hospitals that people were willing to walk away from, wanted to sell, wanted to close, into 11 of the best hospitals any single place in this world. You betcha I’m proud of them.

ATLANTIC YARDS

Jorge Ramos: Let’s go on to another important subject. Mr. Ferrer, you’re against a major economic development project in Brooklyn, the Atlantic Yards. We went to Brooklyn and found this man with concerns about this project. Let’s listen.

Man on tape: We’re talking about Brooklyn, downtown Brooklyn, the Atlantic terminal area that comprises Prospect Heights and the Clinton Hill area. I believe that that area is an area that needs to be revitalized. I believe that the arena, if built, would be an economic boost for the neighborhood, but I’m concerned about whether or not affordable housing will be a key concern if it is in fact developed. That is my major concern. Is it going to be an area that’s going to have affordable housing for residents of the Brooklyn community?

Jorge Ramos: Mr. Ferrer?

Ferrer: You see I don’t confuse economic development projects with billion dollar boondoggles. In fact, this is looking more and more to me like the twin brother of the West Side stadium boondoggle.