Audience Dissatisfaction

Lifelong New Yorker Janet Hague moved to Portland, Oregon, and was immediately struck by how much better the audiences are treated there.

"We get the same shows," she said from Portland -- and she meant concerts, art exhibitions, musicals, plays, films -- "except you can get into them here."

Her judgment may carry an extra sting because Hague happens to be the daughter of Tony Award-winning Broadway composer Albert Hague, who was best-known for his role as the bad-tempered music teacher Mr. Shorofsky in the popular TV series, "Fame" -- which was all about making it as an artist in New York City.

New York is still a great magnet for artistic talent, and (despite Hague's newly-found Portland patriotism) it is easy to argue that New York is home to more shows, and better shows, than anywhere else on Earth.

But how many do you get to see?

The crowds are too big; the wait is too long; the tickets are too high, or the seats are too high up. The people at the box office or Ticketcharge or Ticketmaster are too nasty to have to deal with, or they politely tell you there is nothing available until 2007. The "handling fees" and other miscellaneous charges get your goat. Your timing is never as perfect as it must be -- you get to the phone a half hour after tickets go on sale for your favorite band, say, but that is 20 minutes too late to get anything; or you arrive at the movie theater in what seems like plenty of time for the showing you want, only to discover that the movie is sold out straight through until 1 a.m.

Two new pieces of legislation -- one the governor just signed into law about ticket scalping, the other pending in the City Council about movie commercials -- address specific aspects of audience dissatisfaction, in effect taking as a given that audiences in New York are mistreated. While it is unlikely either will solve the problems, they at least offer hope that the way things are, is not the way things have to be.

Movie Commercials

Movie commercials, which began in earnest in about 1997 (when Regal Cinemas, the world’s largest movie chain, started showing them) irritate people everywhere; one woman in Chicago filed a (failed) class action lawsuit against them, according to a recent article in the Washington Post, “Shhh! The Ads Are About to Start: Pre-Movie Commercial Creep Is Nothing New, But Some Folks Aren't Taking It Sitting Down.”

Movie commercials, which began in earnest in about 1997 (when Regal Cinemas, the world’s largest movie chain, started showing them) irritate people everywhere; one woman in Chicago filed a (failed) class action lawsuit against them, according to a recent article in the Washington Post, “Shhh! The Ads Are About to Start: Pre-Movie Commercial Creep Is Nothing New, But Some Folks Aren't Taking It Sitting Down.”

But movie commercials seem especially irksome to New Yorkers. This is not difficult to explain: It is tough enough (and expensive enough) just getting a seat for a movie in New York. Why then do we have to sit through commercials for credit cards and candy and cola and cars?

Among those irritated is New York City Councilmember Gale Brewer, who has introduced a bill to require movie theaters to disclose the actual time that movies will begin. Right now the advertised movie times are at least 15 minutes before the movie starts, that time being filled with previews (to which nobody apparently objects) and commercials. I had to sit through nine commercials, a public service announcement hitting the audience up for contributions, and six movie previews for some very lame-looking summer flicks before "Batman Begins" actually did.

Hearings on Brewer's bill earlier this month attracted international attention. Sheryl McCarthy dedicated her entire column to it in Newsday, politely suggesting that such a law would not do very much on a practical level - "in Manhattan you have to get to the theater half an hour early to get a decent seat" - but that it was worthwhile symbolically: "This is a revolt against a slew of indignities" (including ticket prices that have climbed in some Manhattan movie theaters to $10.75), a "power struggle between the increasingly greedy theater owners and the city's movie lovers."

The reaction to the proposed legislation from those theater owners was predictable, but entertaining nonetheless. “There should be no legislation on this issue; it is not necessary,” testified Robert Sunshine of the National Association of Theater Owners of New York State. Sunshine said that “consumer complaints associated with pre-show programming and advertising are exceptionally low” and that “legislation will only make the situation more complicated, create potential safety hazards associated with irate customers, cause theater chains to lose revenue and will add additional administrative headaches.”

This might be news to one of the association’s members, Loews, which until earlier this month was the world’s third largest chain of movie theaters, headquartered in New York City. Loews was already telling movie-goers when the films actually begin in their movie theaters, albeit only the ones in Connecticut. Presumably, once they had worked out all those potential safety hazards and headaches, Loews was planning voluntarily to bring the revolutionary practice to the 14 theaters it operated in the city. It is unclear what will happen now that Loews has announced it will be merged into the second-largest movie chain, AMC, which seems much more in denial about audience dissatisfaction.

Whether or not movie-goers take the time to register formal complaints with theater managers, and despite a study by Arbitron (conducted "in consultation" with the theater owners' association and the Cinema Advertising Council)that found that younger moviegoers in particular do not mind commercials(in pdf format), a more recent survey found that 53 percent of moviegoers nationwide believe that movie theaters should stop showing commercials.

One especially adamant opponent of movie commercials is a thoughtful movie-goer named Jason Thompson, who has created a (one-man) organization called CMPAA (Captive Motion Picture Audience of America) and a Web Site, Captive Audience, which offers a sign that you can print out, and leave on your seat while you wait out in the lobby: "Reserved. This patron is avoiding cinema advertising and will return when the feature begins."

In an e-mail exchange with me, Thompson wrote, “the major chains have claimed that they have to show commercials or ticket prices would be dramatically higher. However, ticket prices have continued to rise (about three percent a year on average) despite the introduction of commercials.

”I think that because of annoyances like commercials, parking, giant multiplex crowds and rising prices, people are staying home more often.” Movie attendance, he points out, has declined steadily over the past two years.

Thompson, I should point out, lives in Portland. “Audiences are probably treated better here because there are fewer of us,” he said. “I saw Spider-Man 2 last summer in NYC and the theater was jammed.” (On the other hand, he says, Portland too has to put up with commercials in movie houses, thanks to the “practical monopoly” of the Regal Cinema chain).

Ticket Scalping

New York passed its first anti-scalping statute in 1920, and it has been renewed and debated ever since (including in an article on ticket scalping on Gotham Gazette when the law was up for renewal four years ago) -- a debate that (to oversimplify) pits those who want to make tickets more affordable against those who want to make them more available.

Governor George Pataki has now signed an updated anti-scalping law that is reportedly something of a compromise. Scalpers will be able to sell tickets for shows at venues with 6,000 or more seats at up to 45 percent above a ticket's face value, which is an increase from the previous cap of 20 percent. But that 45 percent will now include all “handling" and other fees that ticket sellers charged to get around the previous, 20 percent cap.

For smaller venues, the cap will remain as before: Scalpers will be permitted to charge no more than 20 percent above face value, or five dollars, whichever is greater.

Anybody who has tried to get into a hit show is aware, of course, that these legal caps have just about zero connection to reality. A recent check of a popular Internet site showed scalpers offering a ticket for the Broadway musical “Spamalot” (which is playing at the Shubert, with just 1,521 seats) for as high as $1,000 – which is about 1,000 percent (not 20 percent or even 45 percent) above face price of the ticket. Out-of-state ticket brokers also offer tickets to NYC shows at whatever price the market will bear.

This was one of the arguments used for getting rid of the caps in New York altogether. Eliminating any restriction on the price of tickets to venues with more than 6,000 seats, Assemblymember Joseph Morelle maintained in the bill he sponsored, would "allow for free market economics to take hold. Consumers will ultimately benefit from the increased supply of tickets and prices will decrease."

The governor rejected this argument, and so does Russ Haven. “There is no 'free market' when it comes to ticket sales in New York, so long as bribery and corruption are part of the system of ticket distribution,” says Haven, who as legislative counsel for the New York Public Interest Research Group has been following the issue of ticket gouging for about eight years.

Haven points to a 1999 report by the Office of Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, entitled “Why Can’t I Get Tickets?”, which details a “corrupt,” “deceptive” system shrouded in secrecy and tainted by “outright criminality” (in the words of the report) that “diverts the most desirable sports, concert and theater tickets away from the general public.”

”There is no reason to believe anything has changed since 1999,” Haven says. “If I’m Joe Fan and I want to see Eric Clapton, I’m competing against multimillion-dollar businesses that are willing to pay anything so that their visiting out-of-town clients can see a good show. That’s why scalping is unfair. It allows wealthy people to drive the prices out of range for everybody else. It's very hard to buy a ticket for anything in New York where you actually pay just the face price.”

What’s A Show-Goer To Do?

The struggle is enough to make you want just to stay home. And, that is increasingly what New Yorkers seem to be doing – witness the rise in DVDs, video games, online activity.

But New York, home of the gouge and the crowds, is also renowned for its alternative culture, and there are alternatives –- out-of-the-way, hole-in-the-wall, independent.

That, anyway, is the pitch of places like Film Forum on Houston Street, which shows no commercials, even though, as general manager Dominick Balletta testified at the council hearing, “we must raise one million dollars every year in order to keep our doors open." But to force its viewers to see commercials, "would reflect unfavorably on the films we are presenting.’’

That was the come-on as well to attend the opening night June 17th of the IFC Center, the new movie theater that replaces the Waverly Theater near West Fourth Street. The Waverly may have been the most famous movie theater in America (thanks to its mention in a song from the musical “Hair,” and its launching of midnight screenings of “The Rocky Horror Picture Show,” which it turned from a studio flop into a cult classic), but it had been shuttered for four years.

Now, the IFC Center was promising a showcase of independent cinema, a hip aura, a cool cafĂ© next door, even a question and answer session with the film’s director – and no commercials, ever.

What the new movie theater delivered on opening night was a sold-out show, a wait for the next show in the "Waverly at IFC" cafe, which charged $14 for "fingerlings" (little fried potatoes), and a giant rat. The rat -- really giant, at least a story tall, and inflated -- was in the curb, next to some screaming union projectionists. “Shame! Shame! Shame!” one kept on shouting on a picket line right next to the movie line. The picketers, from Local 306 I.A.T.S.E., were protesting the failure of IFC to use union projectionists. "We're at the Film Forum, at the Landmark Sunshine Cinema, at all the art houses,” the projectionist explained. “But IFC won’t even sit down and talk to us." ("We're not trying to get jobs where none existed -- we had people at the old Waverly, and we have people at every one of the other theaters in Greenwich Village," union president Michael Goucher told the Voice later.)

Sometimes it really is best to stay home.

Â

City Council Stated Meeting - June 23, 2005

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Gotham Gazette covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

QUOTE OF THE DAY:

"If we can take private property for purposes of a [basketball] arena in Brooklyn, then we can take private property to preserve affordable housing," – Councilmember Leticia James, voting in favor of a bill allowing tenants of subsidized housing to purchase their buildings.

MEETING SUMMARY:

COUNCIL ABANDONS GARBAGE VOTE

New York City Council Speaker Gifford Miller had scheduled a vote on the location of three marine transfer stations that are part of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's proposed waste management plan, but abandoned it when he could not secure the support he needed from other council members.

On June 8, the City Council voted against the three sites by a vote of 29 to 19. The mayor vetoed the council's action, but the speaker did not have the five additional votes needed to override the mayor's veto.

Bloomberg's waste management plan would require each borough to handle its own residential trash. The council was not asked to vote on the entire plan, only to approve three of the four marine transfer stations, slated for the Upper East Side at 91st Street in Manhattan and in Red Hook and Gravesend, Brooklyn. (The fourth location in College Point, Queens has already been approved.)

Speaker Miller, who is running for mayor, has opposed the plan, in large part because the 91st Street station is located in his district.

Last week in an effort to negotiate an agreement, Miller said he would allow a marine transfer station on the Upper East Side, as long as it is used only for recycled paper and would not accept trucks at night. He also proposed three sites on the West Side of Manhattan for handling the borough's garbage.

But the Bloomberg administration refused to negotiate.

"While the administration may feel they have won this battle, the war is far from over," Miller said in a statement.

The mayor's overall waste management plan must still be approved by the City Council in the future. Councilmember Michael McMahon, who chairs the council's sanitation committee, said he will continue to work on reaching an agreement with the administration over the summer.

TENANT EMPOWERMENT ACT

The New York City Council passed a bill (Intro 186-A), dubbed the "Tenant Empowerment Act," that would give tenants of certain kinds of subsidized housing the right to purchase a building if the owner tries to sell it.

Under the legislation, if the owner of a building in the Mitchell-Lama program or with a significant population of Section 8 tenants wants to sell a property, they must give residents 12 months notice. The tenants would then have the "first rights" to purchase the building at a fair-market value.

"If the landlord doesn't want to own a Section 8 building anymore - 'fine, leave,'" said Councilmember Margarita Lopez. "But sell it to the tenants."

While residents would still have to come up with the money to purchase the building, supporters hope that the bill will encourage non-profit community groups to help tenants with financing.

The bill passed by a vote of 47 to 3 with the three Republican members of the council (James Oddo, Dennis Gallagher, and Andrew Lanza) voting against it.

Some have argued that the legislation unfairly interferes with a landlord's right to sell a property as they wish, but council members said that owners will still have the ability to get market value for their properties.

Even if it does restrict a landlord's options, Councilmember Leticia James, who represents Central Brooklyn where developer Bruce Ratner is currently seeking to build a basketball stadium and a series of skyscrapers, said she didn’t see that as a problem. "If we can take private property for purposes such as an arena in Brooklyn, then we can take private property to preserve affordable housing," said James.

Mayor Bloomberg is expected to veto the legislation; the council has more than the 34 votes needed to override the veto.

EXPANDING FOOD STAMP PROGRAM

There are approximately 500,000 New Yorkers who are eligible for federally-funded food stamps, but do not currently receive them. This translates into $1 billion in food stamps that are not being claimed by residents, according to the City Council.

In an effort to expand access to food stamps, the council passed three bills to make it easier to apply and receive the benefits.

Intro 593-A allows people to submit food stamp applications online.

Intro 594-A ensures that food stamp applications are available in city-funded food pantries and shelters.

And Intro 615-A will require the city to accept food stamp applications by fax and allow applicants to skip in-person interviews in cases of hardship.

"We are talking about getting food to people who need it, particularly children," said Councilmember Bill deBlasio.

All three Republicans - James Oddo, Dennis Gallagher, and Andrew Lanza - and two Democrats (Madeline Provenzano and Peter Vallone, Jr.) voted against the bills. Some council members said they are concerned that less stringent application requirements could lead to fraud.

MAKING IT MORE DIFFICULT TO TOW CARS

The council also approved legislation (Intro 312) that would reduce the number of cars that are towed for unpaid fines.

Currently, if a driver has $230 worth of unpaid tickets, city marshals or sheriffs can tow a vehicle. Under the new bill, a person can rack up to $350 in tickets before a car can be impounded.

Councilmember Erik Dilan, who drafted the legislation, said the measure is needed because the city doubled the fines for parking violations in recent years from $50 to $100. It is expected to cut in half the number of cars that are towed each year. The mayor supports the legislation and is expected to sign it into law.

VENDOR DISCRIMINATION

The most divisive vote of the meeting (if a vote of 42 to 8 can be considered divisive) occurred on Intro 491-A, a bill which restricts city officials from inquiring about a person's immigration or citizenship status when applying for a street vendor’s license.

Councilmember Charles Barron authored the legislation, and he argues that street vendors are unnecessarily harassed when applying for licenses to sell food or merchandise on the street.

The measure passed by a vote of 42 to 8; Tony Avella, Dennis Gallagher, Andrew Lanza, Michael McMahon, Michael Nelson, Madeline Provenzano, Peter Vallone, Jr. and James Oddo voted "no.”

"My forefathers came here legally; these folks are here illegally," said Councilmember James Oddo. "And we are setting a structure in place not to question it. We should not be rewarding - in any way, shape, or form – illegality."

WEST CHELSEA AND BENSONHURST REZONINGS

The council approved a rezoning of West Chelsea that officially preserves the elevated rail way, known as the High Line, as a future park. The High Line is a 22-block elevated railway on Manhattan’s west side that has been abandoned for a quarter century. In 2002, the city committed to turning the railway into a public space and officials began working together to select a design team.

The action also aims to create more affordable housing in the Chelsea area. It requires that 22 percent of new apartments built in the neighborhood under new zoning regulations be affordable.

In addition, the council approved a "down-zoning" of Bensonhurst, Brooklyn that limits the density of the housing in the area, restricts the height of new buildings, and preserves one- or two-family houses.

HOMELESS DEATHS

There are approximately 35,000 homeless people living in the city’s shelter system and approximately 4,400 people living on the streets. But the city currently does not keep specific statistics on how and where homeless people die in New York.

The council passed a bill (Intro 127-B) requiring the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to track and report deaths of homeless persons to the mayor and the council in an effort to track exactly how many deaths occur and find ways to provide better health services.

SAFEGUARDING ANIMALS IN KENNELS

It will be safer for New Yorkers to put their dog in a kennel when they go on vacation under legislation that would require pet owners to provide proof of vaccination for certain diseases.

The bill (Intro 498-A) was dubbed "Jazzy's Law" in honor of New York Post columnist Cindy Adams' Yorkshire Terrier, named Jazzy, who died last year while in an upstate boarding kennel.

The bill aims to prevent the spread of diseases from one dog to another. It requires pet owners to show proof of vaccination using health certificates or receipts from a veterinarian, and requires business owners to maintain records including record of immunization, duration of stay, services provided and emergency contact information. Businesses that violate the law would be subject to a $250 fine.

Â

City Council Salaries and Stipends - 2005

2005 Salaries And Stipends For The City Council

Each New York City Council member makes a base salary of $90,000. However, council members can earn an additional stipend or "lulu" ranging from $29,500 to $4,000 for serving in various leadership positions or as a chair of a committee.

East Side Councilmember Eva Moskowitz declined a stipend for chairing the Education Committee and Tony Avella declined $8,000 for the Zoning and Franchise Committee. Youth Service Chair Lew Fidler decided to take only $7,500 rather than the full $10,000. For more, read "Council Lulus, Public Losses" written in 2002.

| POSITION | MEMBER | STIPEND | TOTAL SALARY |

| Speaker | A. Gifford Miller | $29,500 | $119,500 |

| Majority Leader/State and Federal Legislation | Joel Rivera | $21,000 | $111,000 |

| Deputy Majority Leader/Government Operations | Bill Perkins | $20,000 | $110,000 |

| Majority Whip/Rules, Privileges & Elections | Leroy Comrie | $18,000 | $108,000 |

| Minority Leader | James Oddo | $18,000 | $108,000 |

| Minority Whip | Dennis Gallahger | $ 5,000 | $ 95,000 |

| Finance | David Weprin | $18,000 | $108,000 |

| Land Use | Melinda Katz | $18,000 | $108,000 |

| Education | Eva Moskowitz | - | $90,000 |

| Housing and Buildings | Madeline Provenzano | $15,000 | $105,000 |

| Health | Christine Quinn | $15,000 | $105,000 |

| Consumer Affairs | Philip Reed | $15,000 | $105,000 |

| Mental Health, Mental Retardation, Alcoholism, Drug Abuse and Disability Services | Margarita Lopez | $15,000 | $105,000 |

| Women's Issues | Tracy Boyland | $15,000 | $105,000 |

| Aging | Maria Baez | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Civil Service and Labor | Joseph Addobbo, Jr. | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Contracts | Robert Jackson | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Cultural Affairs, Libraries and International Intergroup Relations | Jose Serrano | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Economic Development | James Sanders | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Environmental Protection | James Gennaro | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Fire and Criminal Justice | Yvette Clarke | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| General Welfare | Bill DeBlasio | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Higher Education | Charles Barron | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Immigration | Kendall Stewart | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Oversight and Investigations | Eric Gioia | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Parks and Recreation | Helen Foster | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Public Safety | Peter Vallone Jr. | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Sanitation and Waste Management | Michael McMahon | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Small Business | Dominic Recchia | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Standards and Ethics | Helen Sears | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Technology In Government | Gale Brewer | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Transportation | John Liu | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Veterans | Hiram Monserrate | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Waterfront | David Yassky | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Youth Services | Lewis Fidler | $ 7,500 | $97,500 |

| Subcommittees | |||

| Revenue and Forecasting | G. Oliver Koppell | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Landmarks, Public Siting & Maritime Uses | Simcha Felder | $8,000 | $ 98,000 |

| Planning Dispositions and Concessions | Miguel Martinez | $8,000 | $ 98,000 |

| Zoning and Franchises | Tony Avella | - | $ 90,000 |

| Juvenile Justice | Sarah Gonzalez | $4,000 | $ 94,000 |

| Public Housing | Diana Reyna | $4,000 | $ 94,000 |

| Senior Centers | Michael Nelson | $ 4,000 | $ 94,000 |

| Small Business, Retail and Emerging Industries | Domenic Recchia | $4,000 | $ 94,000 |

| Crime and Substance Abuse | Hiram Monserrate | $4,000 | $ 94,000 |

| Select Committees | |||

| Civil Rights | Larry Seabrook | $4,000 | $ 94,000 |

| Community Development | Al Vann | $4,000 | $ 94,000 |

| Lower Manhattan Redevelopment | Alan Gerson | $4,000 | $ 94,000 |

Â

City Council Stated Meeting - June 8, 2005

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Gotham Gazette covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

QUOTE OF THE DAY:

“The environmental injustice of the past does not justify environmental revenge today or in the future.” - Councilmember Michael McMahon rejecting a plan to build a garbage transfer station on the Upper East Side.

MEETING SUMMARY:

GARBAGE PLAN

The New York City Council blocked a key aspect of Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s proposed waste management plan, which would ship the city’s garbage out of the city by rail or barge, instead of by truck.

Central to the mayor’s plan is the reopening of four marine transfer stations, piers where sanitation trucks can dump garbage onto barges. The trash would then be shipped out of state. (Read an article about the mayor's garbage plan.)

Bloomberg’s proposal has the support of numerous health organizations, environmentalists, and community groups in Brooklyn and the Bronx where thousands of trucks currently ship 50,000 tons of household trash per day through residential neighborhoods.

The council was not asked to vote on the entire waste management plan, only to approve three of the four marine transfer stations, slated for the Upper East Side at 91st Street in Manhattan and in Red Hook and Gravesend, Brooklyn. (The fourth location in College Point, Queens has already been approved.)

City Council Speaker Gifford Miller, who is running for mayor, has opposed the plan, in large part because the 91st Street station is located in his district.

For weeks, both the speaker and the mayor have been lobbying various members of the council and both sides have delayed a vote several times.

Yesterday, the council voted 29 to 19 (with one abstension) to reject the three waste transfer sites. Two members were absent. (See list below for how each councilmember voted.)

In a legislative body dominated by Democrats, usually under the tight control of the speaker, that often votes almost unanimously, this was one of the closest votes in council history. The mayor is expected to veto the decision, and currently the council lacks the 34 votes needed to override the mayor. The mayor has five days to veto; Speaker Miller then has 10 days to try to gain those five extra votes.

The debate in the City Council broke down into two sides.

Speaker Miller and others argued that the council should not give up its power over land use decisions when it still has considerable concerns with the overall plan. They argued that the plan does not do enough to address recycling, handle commercial waste, and reduce overall garbage production in the city. The mayor's plan will also cost an additional $100 million per year.

"This council should not surrender its leverage over the solid waste management plan," said Miller.

On the other side were council members who argued that 80 percent of the city’s waste is processed in four neighborhoods, which are predominantly low-income and minority communities. The proposed plan requires each borough to handle its own garbage.

"This is the best plan so far to show how we are going to get tons of garbage out of the South Bronx,” said Councilmember Joel Rivera.

The speaker and others have proposed alternative sites for Manhattan like West 59th Street or Pier 76 in the Meatpacking District, but so far the Bloomberg administration has not been open to negotiating the locations of the facilities.

“Environmental injustice of the past does not justify environmental revenge today or in the future,” said Councilmember Michael McMahon, who chairs the council’s sanitation committee. “Let’s put together a plan that is good for every New Yorker.”

The day was marked by vigorous debate and backroom meetings, and for a time, the outcome of the vote seemed uncertain.

Earlier in the day, the council’s subcommittee on Landmark, Public Siting, and Maritime Uses actually approved the mayor’s plan by a vote of 5 to 2.

A few hours later, the council’s Land Use committee, chaired by Councilmember Melinda Katz, introduced a resolution rejecting the earlier decision. The committee approved it by a vote of 13 to 9.

By the time the issue reached all 51 members on the floor of the council, some council members felt strong-armed by the speaker and his last minute tactics. “Seventy-two hours before this vote, I began getting phone calls and a whole lot of pressure to vote against this,” said Councilmember Carmen Arroyo.

But others saw the public disagreement as a sign of democracy in the council. ”It's wonderful that we finally have an issue that we can discuss in a relatively intelligent fashion... and disagree," said Councilmember Simcha Felder.

What most did agree about is that the city is still far from a comprehensive plan for disposing of garbage, a problem that has plagued New York for decades.

“At the end of the day, we are going nowhere,” said Councilmember Leroy Comrie. “Both sides have politicized this issue.”

COUNCIL VOTE ON WASTE TRANSFER STATIONS

Voted to Reject the Mayor’s Proposed Sites

Joseph Addabbo

Gale Brewer

Eric Dilan

Lew Fidler

Dennis Gallagher

James Gennarro

Vincent Gentile

Alan Gerson

Eric Gioia

Robert Jackson

Melinda Katz

Oliver Koppell

John Liu

Margarita Lopez

Miguel Martinez

Michael McMahon

Gifford Miller

Eva Moskowitz

Hiram Monserrate

Michael Nelson

James Oddo

Christine Quinn

Dominic Recchia

Philip Reed

Larry Seabrook

Kendall Stewart

Al Vann

Peter Vallone, Jr.

David Weprin

Voted in Favor of the Mayor’s Proposed Sites

Carmen Arroyo

Tony Avella

Maria Baez

Charles Barron

Yvette Clarke

Leroy Comrie

Bill DeBlasio

Simcha Felder

Helen Foster

Sarah Gonzalez

Tish James

Andrew Lanza

Annabel Palma

Bill Perkins

Madeline Provenzano

Diana Reyna

Joel Rivera

Helen Sears

David Yassky

Abstained from the Vote

Allan Jennings

Absent

Tracy Boyland

James Sanders,Jr.

Unfunded Mandates and 'Uncontrollables'

|

When school authorities in Cobb County, Georgia, suggested assigning Deena Chachkes to a classroom with 10 other children, her parents balked. They reasoned that even a small class was too large for Deena, then three, who has autism. "You might just as well have had committed her, at that point, to some long-term facility," her father told NBC.

Researching alternatives, Jacob and Bonnie Chachkes found the McCarton School on Manhattan's East Side. It has one teacher for every child and offers a variety of highly regarded therapies. So eager was the family to place Deena there that they moved to New York. But they still needed to cover the $80,000 a year tuition. And so the Chachkes demanded that the City of New York pay, citing a federal law requiring that all students receive a free education appropriate to their needs and abilities. According to the Chachkes, the courts ruled that the city Department of Education must reimburse them for their daughter's tuition.

The Chachkes framed their experiences to demonstrate that parents with disabled kids have to fight for their children. But some observers, including many in city government, might find a different moral in Deena's story. To them, it indicates how laws passed by the federal government and then interpreted by the courts create huge expenses for state and local governments. Often the federal government provides little or no funding to help cities and counties meet their new responsibilities.

New York politicians have long complained that much of the city's budget and many programs are determined not in City Hall but in Washington, in Albany and in courtrooms. They call them unfunded mandates, or nondiscretionary spending, or uncontrollables, and they say that these expenses restrict local government's ability to create its own programs or to cut taxes.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg is the just the latest public official in the city to complain. In his recently-released executive budget, Bloomberg cited what he called nondiscretionary spending totaling $21.5 billion in the coming fiscal year, or nearly half the budget. These are costs, he implied, over which he has no control.

But others say that the mayor and other public officials have far more control over these expenditures than they would like you to believe.

DEMOCRACY BY DECREE?

Former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani used to complain that so-called unfunded mandates were, in effect, undemocratic. "Some of it you would make the political choice to do in the way in which you're mandated to do it, and some of it you'd probably choose [to do] very, very differently," he told CNN in 1994. "So probably 25 to 30 percent of your budget is moving in a direction where, if you had the decision-making at the local level, you'd make the decision not to spend the money that way."

But others see it differently. Efforts to limit unfunded mandates "strike at the very heart of the body of laws that binds us together as a progressive society and with the highest standard of living in the world," Representative George Miller of California told Congress in 1995.

Many of the unfunded mandates begin with a federal law, says David Schoenbrod , a professor at New York School of Law who has written extensively on the subject. Then, a government agency issues regulations to enforce that law. Finally, federal judges issue consent decrees setting a range of requirements on what local government must do to adhere to those regulations. While these are supposedly negotiated between plaintiffs and local government, the plaintiff's lawyers usually have the upper hand.

"Every recent New York mayor has discovered that his ability to change city policy is sharply curtailed by such judicial decrees. Every mayor has damned decrees for restricting choice, distorting priorities, and frustrating reform. But every mayor … has authorized the city to consent to more of them," Schoenbrod and Ross Sandler, a former New York City transportation commissioner, wrote in City Journal in 1994. The mayors agree to the decrees in order to end the legal battle, implement policies that they may support and "transform themselves from lawbreakers into law implementers."

But the decrees never end, says Schoenbrod who, with Sandler wrote a book entitled Democracy by Decree: What Happens When Courts Run Government. A decree arising out of a case filed in 1975 governs aspects of special education in the city. Court cases from the 1970s and 1980s oversee the city's treatment of the homeless.

REALLY OUT OF CONTROL?

The Citizen's Budget Commission recently published a report entitled "The Myth of the Uncontrollables," (.pdf format) that argues that mayors may not be as powerless as they claim. "These are large, large items," said Elizabeth Lynam, deputy research director of the Citizens Budget Commission, "and the city should be pounding on the bully pulpit and saying we're not going to tolerate it. In many cases, the city itself made decisions that led to some of these expenses.Here are some of the categories of spending that city officials have said are beyond the control of city government, and the ways in which, some fiscal monitors say, they can be brought under greater control:

Medicaid

Medicaid, a federal program to provide health insurance for the poor, is jointly funded by Washington and the states and has become "the poster child for unfunded mandates," said Lynam. It ranks high on the mayor's list of nondiscretionary items.

Unlike many states, New York requires local governments to shoulder a substantial share of the state portion of Medicaid costs -- about 18 percent for New York City according to a 2003 report (.pdf format) by the Independent Budget Office. To make the budget situation worse, Washington gives states a great deal of latitude in determining what services to provide under Medicaid. Albany has been very generous, making New York's program the most expensive in the country, the IBO report says.

Bloomberg estimates the city will spend $4.9 billion for Medicaid next year and $5.3 billion by 2009.

Local officials from throughout New York State have sought to have Albany pay more of the Medicaid costs. But with the state facing its own budget woes, a major shift seems unlikely. "Merely redistributing the burden is not enough," Governor George Pataki said in his 2005 budget address. "The state can no more afford to pay for the current and future costs of Medicaid than counties can."

Instead, Pataki made several proposals, generally described as modest, to cut spending and bring in revenue. These include putting a cap on local Medicaid spending, cutting some reimbursement rates to hospitals and nursing homes, and raising their taxes.

The legislature has rejected some of these measures in the past, according to the Albany Times Union. This year, the union representing health care workers has campaigned against the changes, saying they threaten "our frail elderly, our millions of uninsured New Yorkers, and our sick and injured children" and would damage large academic medical centers, which the union calls "the crown jewels of New York's healthcare system."

But in "The Myth of the Uncontrollables," the Citizens Budget Commission recommends further cuts, including reducing payments to hospitals and nursing homes, greater use of managed care, and limiting the number of hours a patient can receive service from a home health care attendant. The city and state should work together, Lynam said, to stem "the flow of benefits to middle and upper middle class people in the state" while preserving help for the poor.

The Safe Drinking Water Act

To comply with the federal law to insure Americans have clean, healthy water, New York City must build a plant to filter drinking water from its Croton Reservoir system. The city Department of Environmental Protection's 10-year capital plan issued in 2003 includes about $1.5 billion for the facility. Some of this money will be financed through the sale of bonds, some from increases in water and sewage fees, according to the Independent Budget Office.

For now, Washington has let the rest of the city's drinking water remain unfiltered. But if the reservoirs were to become polluted, the federal government could require additional filtration plants costing $6 billion.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

Speaking to a presidential commission in 2002, then New York Schools Chancellor Harold Levy complained of what he saw as excesses in federal rules intended to insure disabled kids get a good education. Affluent parents get the city to pay for expensive private schooling and drain "resources that are critically needed for the system," he said. "You cannot give one kid the Cadillac and the others the back of the bus."

But not all students use the laws to win expensive educations. And advocates say the laws, regulations and courts are needed to insure that the city does not neglect students who need extra help.

They could point to another autistic child, identified as A.J in court papers (.pdf format) filed by Advocates for Children. His individual education plan - a document required for all special education students - called for him to be in a regular classroom. But in fall 2002, his Brooklyn elementary school removed A.J. from all his classes and kept him alone in a room with only an aide for instruction and company. He was allowed to return to his regular class only after Advocates for Children instituted a hearing for A.J. and his guardian.

According to one estimate, the city spends $2.7 billion a year on special education. While much of the money goes to services within public schools, the Department of Education will also pay for about 6,200 kids to attend specialized private schools this year.

Despite federal law and court rulings, the city may have more options than is often claimed, Lynam said. "Once a kid is in special ed, there is a mandate, but the city has a large degree of control over whether a kid gets into special ed," she said. In the past, the Citizens Budget Commission has urged the city to take steps to provide needed services to kids while not classifying them as special education students - a designation that sets off a chain of rules and requirements.

Employee Related Expenses

Pensions, health insurance and other fringe benefits for city employees and retirees continue to rise.

Bloomberg has budgeted $9.6 billion for these items in 2006 and expects them to increase by another $1 billion by 2009.

In some respects, the city has tied its own hands here. In negotiations with its unions, it agreed to various benefits that it must now honor.

But Albany has played a role too. For example, it passed a law giving retired public employees cost of living increases in their city pensions. This will cost the city $820 million a year by 2010, according to Doug Turetsky of the Independent Budget Office. And the state constitution requires that current workers receive the pension plan now in effect.

But nothing stops the city from trying to persuade the legislature to adopt a new plan for future employees, the Citizen Budget Commission says. It recommends that the city switch from its plan that guarantees a benefit to a "defined contribution plan," where employers and employees put in a set amount that is then invested for use upon retirement. This type of plan is now favored by the vast majority of private businesses. The city could also end its unusual practice of letting overtime pay count toward pensions.

Like most employers, the city is seeing the cost of providing health insurance to employees rise. While some of that is unavoidable - a product of the overall health care situation in the country -- the Citizens Budget Commission notes that the city is more generous with health insurance than many employers. For example, it says, city employees and retirees, unlike most other workers, do not contribute to the costs of their health insurance. This could be changed in future agreement with municipal employee unions.

Debt Service

The money New York must now pay to service its debt was originally very much under the city's control -- citizens wanted schools, roads and other capital projects and the city borrowed money to pay for them. But now the city has to pay back the loans - with interest. This will cost $4.3 billion and climb to $5.8 billion in 2009 - an increase of more than 36 percent, the city says. "Every dollar spent on debt service is a dollar that you don't spend on the day-to-day expenses of the city," Douglas Offerman of the Citizens Budget Commission has said.

Some budget advocates recommend cutting debt service in the future by building projects more efficiently or by switching some capital items to the operating budget. In its report, the Citizens Budget Commission calls for spending some of the city's current $3 billion surplus to pay off debt.

FEDERAL EFFORTS TO CURB UNFUNDED MANDATES

Any major change in unfunded mandates facing New York and other cities would have to come from Washington.

And so in the 1990s while Giuliani complained about unfunded mandates in New York, Republicans made unfunded mandates and the court orders a linchpin of their Contract with America.

"Americans do not want Washington, D.C. running schools, college, law enforcement, city parks and most roads," Senator Lamar Alexander of Tennessee, a staunch opponent of unfunded mandates, said. "Put too may one-size-fits-all jackets on Americans, and this country will explode."

In response to such concerns, in 1994, Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act. It required that congressional committees estimate the costs their actions would place on state and local government and private companies. If the expense was estimated to be above $50 million a year ($100 million for companies), a majority of Congress had to agree the benefit was worth the cost. The law did not eliminate any existing requirements; it merely restricted Congress' ability to create new ones. And it does not bar Congress from cutting funding to finance existing programs, leaving the state to pick up the slack.

Despite the limitations, the Congressional Budget Office concluded that the number of bills containing mandates that would be covered under the law decreased by more than a third between 1996 and 2002. The measure has "fundamentally changed the relationship" between the national government on one hand and state and local government on the other, one of its sponsors, Dirk Kempthorne, now the governor of Idaho, said on the law's 10th anniversary.

But others are less effusive. The law "is a step in the right direction, but still quite a limited one," Pietro Nivola of the Brookings Institution has written.

To tighten the law, Congress recently approved a report requiring a 60-vote majority in the Senate to approve an unfunded mandate. Until then, a simple majority was enough.

Alexander has proposed the Federal Consent Decree Fairness Act aimed at the courts. Other have suggested that the federal government adopt a law saying no government could pass a law requiring a lower level of government to pay for a program without compensating them. This would apply to Albany as well as Washington.

THE LATEST BATTLES

Since the Republicans gained the White House and Congress, the battle lines over unfunded mandates have shifted. This is glaringly apparent in the debate over President Bush's sweeping education law, No Child Left Behind. A suit recently brought by the National Education Association, the country's largest teachers union, challenges the law as an unfunded mandate. The union says Congress promised states $122 billion over four years to implement the law's increased testing and teacher certification requirements, but only delivered $95 billion. Connecticut and some local school districts have filed similar suits. (New York has not been involved in these actions.)

But Brian Riedl of the Heritage Foundation and some other conservatives counter that the education law is not an unfunded mandate because states do not have to comply with it - if they are willing to give up millions in federal education money.

As politicians seek to limit unfunded mandates, new ones loom on the horizon. Congress recently passed a law requiring people applying for driver's licenses to show more identification. It will also bar undocumented immigrants from getting driver's licenses. Some critics see this as yet another unfunded mandate - creating headaches, increasing bureaucracy and costing the states $750 million.

And if it is upheld on appeal, the court ruling that the New York City schools receive an additional $5.7 billion in city and state funds could turn out to be one of the biggest unfunded mandates of them all.

For more information

NEW YORK CITY

The 2006 New York City Budget

(Gotham Gazette)

Caution: Budget Pitfalls Ahead

(Gotham Gazette)

What Can Any Mayor Really Do?

(Gotham Gazette)

Analysis of the Mayor's Executive Budget for 2006 (.pdf format)

(Independent Budget Office)

The Myth of the Uncontrollables (.pdf format)

(Citizens Budget Commission)

A report on four areas of spending often viewed as beyond a mayor's control and what the city can do about them.

Setting Higher Standards For Special Education In New York City (.pdf format)

(Citizens Budget Commission)

A Short Guide to Special Education

(Advocates for Children)

Taming New York's Medicaid Beast

(Newsday)

GENERAL

Democracy by Decree

by David Schoenbrod and Ross Sandler. How the courts control public policy.

Fiscal Millstones on the Cities: Revisiting the Problem of Federal Mandates

(The Brookings Institution)

A look at how the Unfunded mandates Reform Act has worked and what other measures could be taken.

The Head Ignores the Feet

(The Economist)

The Bush administration seems indifferent to the budget crisis in the states.

States Get Stuck With $29 Billion Bill

(National Conference of State Legislatures)

How the unfunded mandates add up.

The Supreme Court, Democracy And Institutional Reform Litigation (.pdf format) by Ross Sandler and David Schoenbrod

(New York Law School Law Review)

A discussion of efforts to limit court decrees.

Those Unfunded Mandates by David Broder

(Washington Post)

The 10th anniversary of the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act

What Unfunded Mandates? by Brian Riedl

(National Review)

A fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation argues that the state's budget woes should be blamed on the states"

Unfunded Mandates

(General Accounting Office)

A report by this federal agency on the effects of the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act

Â

The Citizen

|

The Citizen has moved to a new location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

New Voting Machines

This fall will be a historic election, not because New Yorkers will be deciding who the next mayor will be — we do that every four years — but because we will be doing it for the last time on the familiar voting machines that have shown up in our churches, schools and community centers every fall for more than four decades.

Yes, the Shoup 3.2 lever machines, those awkward metallic boxes long in need of replacement, will be gone after November, if all goes the way it is supposed to.

What will replace them?

The New York State Legislature was supposed to decide that, following guidelines from the federal Help America Vote Act, or HAVA , passed by Congress in 2002 in response to the chaos of the 2000 Presidential election. But, after failing for years to agree on a uniform statewide voting machine, state legislators are deciding not to decide. Instead, they will leave it up to each of the state’s 62 counties.

For better or for worse, decision-making on New York City’s next voting machines will now rest with the New York City Board of Elections.

Choice Of New Machines

There are two main contenders to replace the antiquated lever machines used currently. There are optical scan machines, much like the fill-in-the-bubble “scantron” system used to administer standardized exams. Then there are direct recording electronic machines (DREs) more closely resembling ATM cash machines.

While the replacement of our lever machines was never in doubt, the challenge for the state legislators has been deciding which of these types of machines we should choose; how stringent the standards should be; and who would make the decision on machine purchase.

Since HAVA set only bare minimum standards for new machines, state legislatures are empowered to set additional standards — such as a voter verifiable paper trail to ensure machine counts are accurate in the case of discrepancies — and even select a statewide machine should they choose to do so. However, these decisions can also be left to the counties.

No Agreement By State Legislators

Forging an agreement on machines in the New York State Legislature has proven to be nearly impossible. For two years now the legislature has made only piecemeal progress towards any decision, its delay pushing New York State to the brink of non-compliance with HAVA and the loss of over $153 million in federal funds for New York. As the State Assembly pushed hard for inclusive and uniform statewide standards to ensure greater and equal access for all voters across the state, the State Senate held firm on stricter language to ensure security and prevent against potential voter fraud. The clash of these positions has prevented a compromise.

It now appears that the Democrats in the Assembly are ready to concede their position on a mandated statewide machine, and the counties will be in charge of their voting machine purchases. In light of the inability of our State Legislature to work across party lines and between houses, it is no great surprise that they cannot come to a conciliatory agreement. But as New York has dragged its feet on this key provision of HAVA, as well as the bulk of HAVA’s other requirements, we are currently one of the last states to remain in non-compliance with the federal legislation. And with the quickly approaching January 1st deadline the state has positioned itself to face numerous challenges above and beyond the replacement of the old machines.

County Officials: Winners or Losers?

With the State Legislature in Albany deciding not to decide, county officials across the state are now faced with a rushed timeline, as well as sudden pressure from lobbyists for machine vendors and various advocates, who up until now were focusing their efforts in the state capital. Many civic groups are concerned that with the fragmented procurement process, and the millions of dollars in contracts that are at stake, transparency and accountability will be compromised as regulations governing lobbying on a local level are more opaque than at the state level.

Whatever new machine is picked, the counties will have to launch massive voter education efforts with new and old poll workers having to be trained or retrained en masse. Technicians will have have their hands full ensuring that the post-Shoup era is launched successfully. Troubleshooting will need to be done on the fly.

New York City, with close to four million voters, may face the most daunting task of all ahead. While there are five counties in New York City, the New York City Board of Elections acts as a unifying body for the purposes of election administration. According to its executive director, John Ravitz, the Board of Elections had hoped to phase in the new machines over a three election cycle. “That option was taken away from us by the State Legislature,” Mr. Ravitz said at a recent hearing at City Hall.

Under the leadership of Ravitz, the board has not been passively waiting for a decision from Albany; they have been reviewing the different voting systems available since HAVA was passed in 2002. As of yet, they have not reached a decision on what machine best suits the needs of New York City voters.

However, the New York City Board of Elections is viewed generally to be in a better position to negotiate a contract in the absence of a statewide decision because about half of registered voters in the state reside in New York City. With our needs pegged at about 5,000 to 10,000 new machines and each machine costing somewhere between $6,000 to $11,000 (the lower range of both for optical scan and the higher range for DRE) the costs and contracts could be as much as $100 million.

New York City also has unique language and access needs that may have made the negotiating process at the state level more difficult than it would have been otherwise. The ability of New York City to choose a voting system independently of the state, and not settle for a compromise machine that may have come through a statewide uniform system, may just provide the city with flexibility necessary to focus on its unique and important needs. In any case, the clock is ticking.

Doug Israel is the director of public policy and advocacy for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette.

City Council Stated Meeting - May 25, 2005

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

QUOTE OF THE DAY:

“This will end the days when little girls are conditioned to wait on line for the bathroom.” - Councilmember Yvette Clarke speaking in support of a bill to require more restrooms for women in public places.

MEETING SUMMARY:

BATHROOM PARITY

Declaring that the "fight for women’s rights has entered the 21st century," the New York City Council voted to address an issue that has affected women since the invention of indoor plumbing: long lines for the ladies' room.

The legislation, dubbed "The Restroom Equity Bill of New York" (Intro 42-A) would require many public places to provide twice as many bathroom stalls for women as for men.

The regulations apply to new bars, concert halls, arenas, stadiums, auditoriums, dance clubs, and meeting halls, as well as existing establishments that make extensive renovations.

Brooklyn Councilmember Yvette Clark, who authored the bill, recounted a recent trip to the circus where the lines for the women's restroom stretched out the door, while men waited around for their female friends and family members.

"This will end the days when little girls are conditioned to wait on line for the bathroom," said Clarke. "And for the men, who love those women and love their children, and have had to watch us suffer through the indignity of standing on line to use restrooms, today is your day as well."

After negotiations with the Bloomberg administration, the bill was amended to allow some small business owners to make bathrooms unisex in order to reduce costs. Municipal buildings, restaurants, prisons, schools, and hospitals are exempt from the regulations.

Other states, including California, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington, have already enacted similar restroom equity laws.

The measure passed unanimously, and the mayor is expected to sign it into law.

"Sixty percent of the electorate in my district are female, and I definitely don't want to face them in an election year and have to explain my position if I was on the wrong side of this bill," said Councilmember Erik Dilan.

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE FATALITIES

Each year more than 60 women are killed in incidents of domestic violence in New York City.

In an effort to create more collaboration between various city agencies that work on the issue, the council approved the creation of new government committees that will review deaths and injuries resulting from domestic violence. The panels will be comprised of representatives from the police department, shelter system, child welfare system, health department, and organizations that work with women who have been abused.

"This is more than just reviewing data," said Councilmember Tracy Boyland, who drafted the bill (Intro 366-A). "[The goal] is to see if we can catch the signs of domestic violence before it's too late."

FIGHTING FOR CONTROL OF RENTS

Since 1971, the State Legislature in Albany - not the mayor and the City Council - has controlled the city's rent and eviction laws.

This law, named after then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller's housing commissioner, Charles Urstadt, has been the focus of housing advocates for years, who argue that decisions affecting 2.4 million New Yorkers living in rent controlled or rent stabilized apartments should be made by city lawmakers. (Read an article about the Urstadt Law.)

The City Council passed a so-called "home rule message," which calls for the repeal of the Urstadt Law. While the measure holds no legal power, it supports a state bill drafted by Senator Liz Krueger and Assemblymember Vito Lopez, which would give city officials control over rent and eviction regulations.

The three Republican members of the council -– James Oddo, Andrew Lanza, and Dennis Gallagher -– voted against the measure.

COLLECTIVE BARGAINING RIGHTS

Under New York City’s Collective Bargaining Law, certain uniformed employees - police, firefighters, sanitation, and corrections officers - have unique bargaining rights.

The City Council unanimously overrode a veto from Mayor Michael Bloomberg to extend those rights to related positions like emergency medical technicians, sanitation enforcement agents, fire protection inspectors, and school safety workers.

The council argues that its bill (Intro 380-A) is needed because these city workers face hazardous situations on the job, but are not given the same rights as other uniformed employees.

INTERNET CAFES REVISITED

Two weeks ago, the City Council was set to vote on two bills aimed at preventing students from skipping school and spending their days surfing the Web in Internet Cafes, but at the last minute, the council withdrew the bills from the agenda after the New York Civil Liberties Union complained that the measures could infringe on youth rights. (In a previous article, Gotham Gazette incorrectly reported that the measures were passed on May 11, 2005.)

After further revisions to the measures, the council approved them. Intro 65-A requires that Internet cafes obtain licenses from the Department of Consumer Affairs, just as video arcades currently do. And Intro 78-A restricts minors from Internet Cafes during school hours.

Queens Democrat Tony Avella voted against both bills because he said they fail to consider certain issues, like schools that have split sessions.

"Both of these bills should be sent back to committee because they seriously need to be redone," said Avella.

RENAMING JAMAICA AVENUE

The New York City Council is often ridiculed for spending too much time and energy changing street names. But in the case of Jamaica Avenue, which marks the boundary between Queens and Nassau county, the council's action was aimed at more than just honoring a local hero or historic figure.

For years, Jamaica Avenue from 257th Street to the Cross Island Parkway has had two names. The northern side of the street is called Jamaica Avenue; the southern side of the street is called Jericho Turnpike.

Merchants and residents say it is confusing because businesses on opposite sides of the boulevard list different street names in their addresses. Recently, an ambulance was delayed in reaching a sick person on the street because the driver could not locate the correct address.

The council voted (Intro 304-A) to name the entire street Jericho Turnpike.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for June 8, 2005.

Â

City Council Stated Meeting - May 11, 2005

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

Quote of the Day:

"I don’t look at this as a 'stop the stadium' issue. This is something that goes to the heart of our democracy...." - Councilmember David Weprin who supports the West Side Stadium, but voted to block Mayor Bloomberg’s financing of it.

Meeting Summary:

West Side Stadium Financing

In an effort meant to thwart Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plan for the proposed West Side stadium, the New York City Council passed a measure that would prohibit the city from financing building projects using "payment in lieu of taxes" (called PILOTs) without the consent of the City Council.

Mayor Bloomberg wants to use this kind of financing to pay for the city’s $300 million share of the stadium, which will cost a total of $1.7 billion.

PILOTs are money from developers who build properties on city-owned land but do not pay property taxes on it. Instead, they pay money into a specific fund.

Last year, over 260 PILOT programs across the city generated about $47 million in annual revenue. The mayor wants to use a portion of this money to pay off the annual payments on $300 million in stadium bonds over 25 years. None of the PILOT money goes through the city’s usual budget, which must be approved by the City Council.

The mayor argues that this type of financing is already used for various projects around the city. For example, the city used $1.25 million in such financing to help Broadway theaters recover after September 11, 2001.

The City Council, lead by Speaker Gifford Miller who opposes the stadium and is running for mayor, argues that money from the PILOTs fund has never been used for such an expensive project.

"It is wrong for the mayor to try to devote hundreds of millions of dollars of taxpayer money without ever having review from the public budget process," said Miller.

The bill (Intro 584-A) would prohibit funds from being spent without a vote of the City Council and would require the mayor to provide a monthly report of potential projects that may use PILOT financing.

A number of council members have voiced their support for the West Side stadium, but most, including council finance chair David Weprin, still voted for the measure.

"I don't look at this as a 'stop the stadium' issue," said Weprin. "This is something that goes to the heart of our democracy and the checks and balances system."

The council voted 48 to 2 for the measure; only Queens Councilmember Tony Avella and Bronx Councilmember Madeline Provenzano voted against it.

The mayor is expected to veto the measure, and the council has promised to override it. The issue will likely have to be resolved in court.

Williamsburg/Greenpoint Rezoning

New apartments, retail stores, and a waterfront esplanade will be built along the Brooklyn’s East River waterfront under a plan approved by the City Council.

The rezoning changes the parameters of what types of buildings can be built in a 175-block area of Williamsburg and Greenpoint, allowing developers to build taller buildings, putting residential apartments in areas once dominated by warehouses and manufacturing, and creating new open space.

Officials hope that 10,800 new apartments will be built over the next 10 years, of which a third (approximately 3,500 apartments) would be affordable.

The plan will also:

- Create 54 acres of parkland, including a waterfront esplanade.

- Provide $22 million in funds to keep industrial jobs in the area.

- Invest $70 million in the Brooklyn Navy Yard so businesses that may be displaced can relocate.

- And allocate $1 million to improvements to McCarren Park.

Council members David Yassky and Diana Reyna, who represent the neighborhoods, said that the plan provides more affordable housing than any other recent rezoning.

"When we talk jobs, when we talk about affordable housing, when we talk about open space – those are not privileges, those are rights," said Reyna.

Only one member – Charles Barron – voted against the plan. He argued that the city should work toward a goal of making 50 percent of new housing affordable.

AIDS Housing

Last month, in an effort to improve its system of providing housing for homeless people infected with AIDS/HIV, the city passed a law requiring the city to issue quarterly reports on the services and housing it provides to people with AIDS/HIV.

Now, the City Council has passed two complimentary measures.

Intro 535 gives the city 90 days to find homeless people living with AIDS permanent, medically appropriate housing. Currently, many people are moved from various temporary housing sites for up to three years. Intro 543 would create a central system to track the availability of emergency housing to ensure that people are placed more quickly.

Identity Theft

According to the council, approximately 12,000 New Yorkers are victims of identity theft each year, so the legislative body passed a series of measures aimed at protecting residents.

Intro 139-A gives the Department of Consumer Affairs the power to shut down any business that is found to have been involved in cases of identity theft. Intro 140-A and 141-A require city agencies and businesses located in New York City that use personal data to tell residents when information has been stolen.

Scaffolding Safety

With the goal of improving safety for those who work on city scaffolding and the pedestrians who walk underneath it, the council passed a measure (Intro 597-A) that forbids anyone to "erect, dismantle, repair, maintain or modify" scaffolding unless they attend a 32-hour safety course.

"This is very unsexy, but important to the livelihood of our city and the people that work and erect those scaffolding that you see all around the city," said Madeline Provenzano.

311 Helpline Information

Nearly 20 million New Yorkers call the city's 311 citizen help line every month seeking assistance with non-emergency issues.

While many have praised the plan that consolidated 40 different phone numbers for city agencies into one easy to remember number, City Council members argue that the mayor’s office has not been willing to share the results of the calls.

A new bill (Intro 174-A) requires the city to provide information on 311 calls by zip code, community board, City Council district, and borough. The measure is aimed at allowing officials and residents to compare how their neighborhood or borough compares with others in the city.

Lead in Food

Lead in candy and other foods manufactured in Mexico have become a growing concern to health officials. One study in Orange County, California estimated that 15 percent of the children with lead poisoning contracted it through candy imported from Mexico. Prolonged exposure to lead has been associated with memory loss, behavioral problems, and kidney damage.

The City Council passed a bill (Intro 396-A) banning the sale of food and other products containing lead in New York City.

Staten Island Ferry Service

In December 2004, the City Council approved legislation that would establish a minimum level of service for the Staten Island Ferry, requiring that the ferries run earlier in the morning and later into the night. Mayor Bloomberg vetoed the legislation, arguing that ferry schedules should be set by the Department of Transportation as needed, not mandated by the council.

Since then, the two sides have reached an agreement.

Under a new piece of legislation (Intro 636-A), three additional weekday ferry runs will be added. Half-hour ferry service will now be available between 5:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m., and every fifteen minutes between 7:00 a.m. and 8:00 a.m. In addition, a new 1:00 a.m. boat will depart from lower Manhattan. In another year and a half, the city will expand its weekend service as well.

All of the measures - except the PILOT measure and the Williamsburg rezoning - were approved by a vote of 50 to 0. The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for May 25, 2005.

That 70's Show

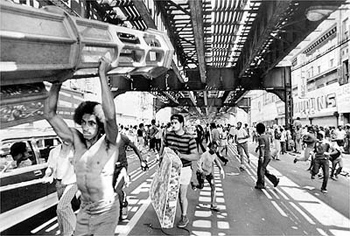

Heavy looting followed a citywide blackout in July 1977 |

Jonathan Mahler met with the Gotham Gazette Reading NYC Book Club at the Jefferson Market Branch of the New York Public Library on April 27 to discuss his book "Ladies and Gentlemen the Bronx is Burning: 1977, Baseball, Politics, and the Battle for the Soul of a City." Mahler argues that the year was a turning point in the city. The edited transcript is below.

Gotham Gazette: This month we are with Jonathan Mahler who is a contributing writer to the New York Times Magazine. His book Ladies and Gentlemen the Bronx is Burning is about the events of the summer of 1977 in New York City. Mr. Mahler is going to begin by reading a passage of the book about the blackout.

Jonathan Mahler: The book is about the year 1977 in New York. I chose that year because, from a narrative perspective, it was very eventful: mayoral race, blackout, [serial killer] Son of Sam, many other things. But also, from a broader perspective I chose that year because it was a pivotal moment when New York went from being one kind of place to a different kind of place. I guess you could say the old New York - this quasi-socialist city with the great free higher education, rent controlled apartments, lots of jobs for the working class - was dying and a new capitalist utopian city was being born. That's the city we live in, with real estate barons and media tycoons and the like.

THE BLACKOUT

I devote a lot of space to the blackout in the book. I tell much of the story of the blackout through the eyes of a group of cops in Bushwick, Brooklyn, which was the neighborhood that experienced the worst looting that night. I had the good fortune to meet these guys as I was researching the book. Obviously, it was a night they couldn't forget, so they all had specific and detailed memories. The narrative that I am going to be reading I was able to piece together through the accounts of these guys.

(reads passage starting on page 187).

Gotham Gazette: How did the blackout and the riots serve as a turning point or the low point of New York at that time?

Jonathan Mahler: Well, this all happened in the heat of a mayoral race. At the time of the blackout, this little-known long-shot congressman named Ed Koch was running for mayor. And his competition, the front-runners were, of course, the incumbent Abe Beame, Bella Abzug, and Mario Cuomo, all of whom were far ahead of him in the polls. But after the blackout, Koch - who was not terribly well known as I said - was able to kind of, for lack of a better word, exploit the bloodlust in the city in this sort of fear of crime. And he ran a real law-and-order campaign, which ultimately led to his election. He campaigned for the death penalty, [even though] mayor has no say in whether or not New York State adopts the death penalty. But it became a campaign issue. Mario Cuomo was adamantly opposed to the death penalty.

One thing Koch criticized Beame for was not bringing in the National Guard in during the blackout. So it became a campaign issue.

I think if one takes a broader view, at the time, the New York City Police Department was really depleted because of the fiscal crisis. And there was not a lot of good will toward the police department, because as a result of those layoffs, there had been a lot of police protests, which people don't like to see. There was one police protest at Yankee Stadium. And while literally thousands of cops were protesting outside Yankee Stadium, drinking beer and holding up protest signs, there were gangs of teenagers mugging people and breaking into cars. If one takes a longer view, I think that something like this that allowed for the emergence of a Giuliani who could really take a much tougher position on crime, and in a sense, in doing so, sort of rescue the police department.

Gotham Gazette: But do you think you can really draw a straight line between the riots after the blackout in 1977 and Giuliani?

Jonathan Mahler: No, not a straight line. But I think you can see that in a sense the city had to bottom out in a way for the people to be willing to endure the things that Giuliani did. They would have been unthinkable in an earlier era, but once the city had been this low, it changed people's perspectives.

Calvin Johnson: How did you weave a narrative together out of all these events? Who did you talk to, and how did you piece together the story that you tell in the book?

Jonathan Mahler: Specifically the blackout?

Calvin Johnson Yes, Part Two of the book.

Jonathan Mahler: Different parts of the section I relied on different sources.

Before I get to Bushwick, I do a pretty lengthy retelling of how New York lost power from inside the control room of Con Edison. I did that largely through the telephone transcripts of the various Con Ed system operators, which were all subpoenaed for a federal investigation and have therefore been made available. I didn't even know they existed, frankly, and then I went down the Municipal Archives to see what they had. It was kind of a great find; it's incredibly dramatic reading. The system operator of Con Edison, William Jurith, you really see him panic. Here's this guy who is at the helm when New York City is about to lose power. So I used those telephone transcripts largely to figure out what had happened. One of the experts who was subpoenaed in the federal investigation to analyze what had gone wrong was very helpful in explaining all the science I had to understand. There were three separate investigations - a city, federal, and state investigation - and I read all of those. There was also all the newspaper coverage at the time, but because of the looting, what had actually gone wrong kind of got overshadowed.