Where Did Hudson Yards Come From? This Little-Known Report Helped Start It All

(photo: Hudson Yards)

Today Hudson Yards is largely described as a billionaires’ fantasy, but in fact it’s a rare instance of the city, state and federal governments partnering to create a strategy to help ensure New York City’s position as the world’s commercial capital. And it has an interesting origin story few may be aware of.

Three months to the day before planes were flown into the World Trade Center, a little-known, but important report was issued by a group convened by New York Senator Chuck Schumer and dubbed the “Group of 35.” Largely a wonky urban policy piece, the report called for the public sector to take a much more proactive role in supporting future commercial development in the city.

In spite of the robust economy that the city enjoyed in the late 1990s, the report painted a dire picture of the future of commercial development in New York. The cyclical nature of the commercial real estate market was highlighted as a series of booms and busts that challenged any strategic and comprehensive approach to new development. According to the report, if the city didn’t take action to help increase the supply of new space, “New York City will miss out on hundreds of thousands of new jobs and increased economic activity in the next 20 years.”

Ironically, in New York City the crash of the early 1990s was good for new and growing companies to find plentiful and cheap space for expansion, but by the late ‘90s there was a growing concern that there wasn’t enough space to support future employment.

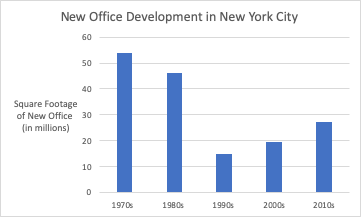

Looking forward, the report anticipated that New York City would add nearly 600,000 jobs over the next 20 years, half of which would be office-based. The city would need 23 million square feet of new office space over the next 20 years and an additional 60 million square feet thereafter through 2050. Looking at the development trends of the previous decade, construction had all but stalled for new office space. The city’s development market was paralyzed.

The report concluded dramatically that the city “office market was in a space crisis by the end of 2000.” New York lagged other cities through the 1990s, and over half of new office space built in the region occurred outside the city.

Hudson County, New Jersey was seen as particularly competitive; the report noted that from 1997 to 2000, more than a dozen companies moved from New York to New Jersey to occupy 6 million square feet of space in Hudson County alone, with 30,000 jobs lost in those moves.

There were substantial barriers to new development, largely as a result of the boom and bust cycle. Both physical and financial barriers stymied new development across the city, and particularly in Manhattan. The physical constraints were predominantly around land, the lack of available sites, and the appropriate zoning to promote substantial new development.

In terms of the financial constraints, in spite of a strong real estate market, rents were still not high enough to support new development and lenders’ requirements for financing were too restrictive except for the largest and most credit-worthy tenants.

So given the historical boom and bust cycle of real estate development, coupled with the physical and financial constraints, the Group of 35 put forth a Commercial Development Strategy for New York City, primarily focused on creating new commercial business districts (CBDs) for the city to keep pace with the competition that it was facing both regionally and nationally.

While there were a number of recommendations for relief from the high real estate taxes paid by developers and their tenants, the Group of 35’s “most ambitious component” was the creation of new and expanded CBDs. New CBDs were called for in both Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City, but the most radical idea was the creation of the new CBD in Manhattan.

For much of its history, Manhattan business was centered in Lower Manhattan. It wasn’t until the early 20th century, with the creation of the first subway in 1904, that development, and particularly office-related uses moved to Midtown. By the mid-20th century, Midtown had largely overtaken Lower Manhattan as the premiere office district in the city. And in spite of numerous attempts to revitalize Lower Manhattan, Midtown still commanded significantly higher rents. As a result of the strength of this market, Midtown was essentially “full.” There were no available sites for significant new development in Midtown -- the Far West Side beckoned.

With the increasing office activity on Manhattan’s West Side, thanks to the redevelopment of Times Square, the Far West Side appeared as a “natural” extension to midtown. It had adjacency to regional connections at Penn Station, the Port Authority Bus Terminal, Hudson River ferries, the West Side Highway, and the Lincoln Tunnel. In spite of these connections, the neighborhood was highly underutilized with surface transportation uses, vacant lots, and a low population density. There was also space to accommodate large-scale development above the MTA’s West Side Rail Yards.

Interestingly, there was not one mention in the report of the High Line, which would eventually become one of the most significant components of the development of Hudson Yards and west Chelsea in the 2000s.

But there were significant obstacles to developing the Far West Side, including the lack of subway access and low-density zoning. An innovative strategy was put forth to extend the 7 subway line through the use of tax increment financing to help pay for the extension.

In 2005, thanks to a massive rezoning led by the city that laid the groundwork for over 40 million square feet of new development, Hudson Yards was born. To create the necessary commercial anchor for the neighbrohood, the MTA and the City teamed up in 2007 to issue RFP’s for massive development over the MTA’s west side rail yards. The MTA also built a grand new 7 subway station that opened in 2012 with city funding in an all too rare example of intergovernmental cooperation and mutual support.

Hudson Yards has transformed a large swathe of Manhattan with a bustling new office district. According to JLL, nearly 8 million square feet of new office space has been built and occupied to date, and another 8 million more square feet of space is under construction and largely pre-sold or pre-leased. Hudson Yards is already providing nearly twice the amount of space built in the entire city in the 1990s.

Today, the city is enjoying office employment at a historic high of 1.97 million jobs versus a low of 1.65 million in January 2010. While we cannot only give credit to the Group of 35 for their vision in anticipating the need for all this space, we should appreciate and learn from their foresight in giving New York City a strategy to be proactive in the creation of new business districts to help feed the engine of economic growth in this city.

It almost seems laughable today to even consider competition from Hudson County, New Jersey, but at the turn of the last century there was a real threat to New York City’s dominance as a commercial capital from regional office markets. Before we take for granted the glittering skyscrapers, new subway, and expansive parks that now dot the skyline and streetscape of the West Side of Manhattan, we should remember the thoughtful, balanced, and proactive planning that went into making happen.

***

Michael M. Samuelian, FAIA, AICP, is the founder of Samuelian Consulting LLC and an adjunct professor at Cooper Union. He was previously President and CEO of the Trust for Governors Island and, prior to that, a Vice President of Planning and Design with Related Companies. He will be teaching a seminar on the development of Hudson Yards at the Yale School of Architecture this semester.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

6 Keys to Reduce the Number of People Sleeping on the Streets and in the Subways

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

The city’s homelessness crisis is well-documented and deeply troubling, including far too many people sleeping on the streets and in the subways. If it seems like there are more and more people in those situations, it is because there are: the estimated number jumped 23% from 2018 to 2019, based on the one-night winter HOPE Count, to about 3,500 in total.

The city’s efforts to reduce the street population have mostly failed. Nothing emphasizes this failure more than the recent murder of four homeless men who were sleeping on the streets in Chinatown.

The mayor's response to this tragedy was to increase the number of outreach workers and urge other city workers to call 311 about people living on the streets. However the city’s own statistics show that the number of placements into housing has actually dropped, per the Mayor’s Management Report (MMR), after having risen.

In addition, reporting has shown that many of the homeless people on the streets have been told that they must be seen on numerous occasions in the same spot in order to prove that they are homeless and qualify for a caseworker. If this wasn't bad enough, the process, once it begins, can take up to nine months before someone gets a placement in supportive housing.

There is an option other than going into a dangerous shelter, which many homeless people living on the streets or in the subways fear, or staying on the streets and in the subways, which is going into a drop-in center. Unfortunately, these drop-in centers were reduced by 50% during the Bloomberg administration.

A drop-in center is an oasis for homeless individuals living on the street. They can get food, clothing, showers, medical care, and meet with a social worker. These centers do not have beds, they have chairs but there is an option for people to be transported to a shelter or local church or synagogue where volunteers will help them stay for the night.

I have been advocating in writing and on television for four years for the city to increase the number of drop-in centers and the response has been to only open one part-time center in Queens. We need more -- there are only five full-time centers and only two of them are in Manhattan, which is the epicenter of street homelessness.

The most effective method for reducing homelessness has always been supportive housing. I ran two supportive housing programs, which provide a homeless person who is disabled, usually from mental illness or substance misuse, with an apartment and a social worker. Unfortunately, once again the city has failed in this effort, with placements at a 14-year low with only 1,300 supportive housing units opened of 15,000 promised four years ago, or less than 10%. These incredibly slow building and placement rates must be accelerated immediately.

The city recently announced the expansion of outreach efforts and addition of 1,000 safe haven beds. This is a step in the right direction as safe havens have only one or two clients in a room and are considered much safer than a regular shelter. Which begs the question: why aren't the other 12,000 beds for single adult males safe?

The number one reason people on the street give for not going into shelter is fear. Many of them have had bad experiences, ranging from assault to robbery. In fact a recent exposé by The City showed that crime is rampant in the single adult shelters and the Mayor's Management Report shows a 25% increase in serious violent incidents in adult shelters. A few weeks ago, two homeless men in an Upper West Side shelter got into a fight and one stabbed the other to death.

These shelters are patrolled by Department of Homeless Services peace officers and private security guards. The peace officers do not carry guns but they have tasers available to them and they have the power to make arrests. I have advocated for the NYPD to take a greater role in shelter security and a few years ago the mayor decided that the NYPD would supervise the security operation. However, a handful of officers is not enough.

The city should institute a 90-day pilot program where NYPD officers would be stationed 24/7 in the city’s two worst men’s shelters, at 30th Street and First Avenue and the Bedford Atlantic Armory, to support the DHS officers in their duties.

This suggestion will probably be met by criticism from some advocates as criminalizing those experiencing homelessness, but the fact is that homeless people are the victims of crimes committed inside the shelters to such an extent that many would rather sleep on the streets.

In addition to this pilot, the state must stop dumping thousands of newly released former prisoners into the shelter system. They must do a better job of discharge planning and setting up halfway houses to assimilate that population into society.

As we see more homeless New Yorkers on the streets and in the subways, it is time for new action by our government officials.

***

Robert Mascali is a former Deputy Commissioner at the NYC Department of Homeless Services and Vice President for Supportive Housing at Women in Need.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Pursuing More Justice: Elder Parole is Good for Communities Across New York

(photo: Andrew Bardwell/Wikimedia Commons)

When I was first elected to the New York State Assembly in November 2016, I pledged to promote safety, fairness, and justice for my community and other communities across New York. I knew that we had so much work to do to support everyday New Yorkers and their loved ones, especially those harmed by the criminal justice system—something that has impacted me and so many others in my northern Manhattan district for decades.

While colleagues and I made important changes to New York’s pre-trial legal system in 2019, we still have so much to do for the more than 45,000 people currently incarcerated in state prisons and their families. We should start by promoting a system of hope and redemption for long-serving incarcerated older New Yorkers.

In the last two decades of mass incarceration, our system has become smaller but increasingly more punitive. As the overall prison population in New York State decreased since its peak population of 72,000 people in 1999, the rate of people serving life sentences has ballooned.

New Yorkers are now serving more time on longer prison sentences than ever before. Today, one in five New Yorkers in prison is serving a life sentence—more than 9,000 total people. Of this group, 1,027 people are serving life without parole and virtual life without parole (with a minimum sentence of at least 50 years) sentences.

They are effectively sentenced to die in prison without any individualized assessment, public safety review, or second chance. Many of these people are already in their fifties and sixties. Those who aren’t yet elders are destined to become older people in prison given the long sentences they have.

The large majority of people growing older in prison and serving life and death sentences are people of color. Stanley Bellamy is one of them.

In 1985, the year I was born, Stanley was a 23-year-old young person from Queens who made a terrible choice that caused devastating harm. He and several others robbed two people at gunpoint, killing one, and causing serious injury to the other. Their actions left family members of the victims forever harmed and a community shaken. Stanley was sentenced to 62.5 years to life in prison, effectively sentenced to die behind bars without any chance for redemption.

Stanley is now a 57-year-old father, grandfather, mentor, teacher, and positive force in every prison in which he has ever been confined over the last 34 years. He has founded and facilitated victim awareness, restorative justice, and other programs that allow him and his incarcerated colleagues to develop insight into the harm their crimes caused.

Stanley has earned two college degrees behind bars with honors and has accomplished more under the constraints of maximum-security confinement than most people have in the free world. While there is no doubt that Stanley caused serious harm to people, families, and an entire community, his continued confinement serves no purpose other than punishment and revenge.

I believe we are all better served with Stanley and others like him in our communities where they can continue to be positive embodiments of redemption.

Allowing Stanley and other incarcerated older people who have already spent decades in prison a chance at redemption would benefit the communities I serve and others across New York State. Upon release, Stanley and his peers could positively impact all of us in ways that so many other formerly incarcerated community leaders already do.

They’d mentor young people, prevent gang and gun violence, and steer 23-year-old ‘Stanleys’ down a different path. Stanley wouldn’t be a risk to the community but would instead enhance community safety and deter crime.

My colleagues and I in the New York State Legislature have a great opportunity to give Stanley and others a chance, and benefit our communities, by passing the Elder Parole Act (A.9040) in 2020.

Elder Parole would allow the State Parole Board to give people in prison aged 55 and older who have served 15 or more years an individualized review and assessment. The bill doesn’t release a single person from prison. Instead, it provides hope and a chance at redemption for people who are otherwise serving death-by-incarceration sentences.

If the Parole Board decides to release even a handful of people as a result of the bill’s passage, it would save lives, reunite families and communities, and save New York taxpayers millions of dollars.

New York is a national outlier when it comes to long and life prison sentences. Our state has the eighth highest rate of life sentences in the country—greater than Texas, Oklahoma, and Georgia. Far more people have died in the last decade in New York state prisons because of long prison sentences than the total number of people who were executed in every state that still uses the death penalty.

Death-by-incarceration is an abomination that can’t go on any longer. I refuse to have my five year-old daughter grow up in a state that condemns people who look like her to die in cages, regardless of their change and transformation over years and decades. For New York to be the truly progressive beacon that all of us want it to be, we must take steps towards unraveling this paradigm of permanent punishment. Elder Parole is one concrete way for us to get there this year.

***

Assembly Member Carmen De La Rosa represents District 72, including Inwood, Washington Heights, and Marble Hill in Manhattan. She is the lead sponsor of the Elder Parole Act (A.9040). On Twitter @CnDelarosa.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.