New York City Needs a Development Reset – Starting with Public Land

City-owned building at Vernon Blvd & 44th Dr (photo: Memo Salazar)

2019 may go down in history as the year public disenchantment with New York City’s land use policies reached a boiling point.

In June, protestors disrupted a meeting about a neighborhood study for a potential rezoning on Southern Boulevard in the Bronx, claiming that city agencies did not really want their opinions. In August, a judge heard arguments in a lawsuit challenging the 2018 Inwood rezoning, with groups in that Upper Manhattan neighborhood charging that the environmental impact study undertaken there was illegitimate. In September, resident groups publicly assailed City Council Member Carlos Menchaca when he proposed to enter into community benefits negotiations with Industry City Associates, which had applied for a private zoning change in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park. That same night, Queens activists turned an Economic Development Corporation-sponsored meeting about the Sunnyside Yard master plan into a raucous “teach-in,” loudly expressing their conviction that the city was failing to elevate the public interest over the aims of real estate developers.

What explains this increasing lack of faith in government’s good intentions?

Part of the problem, as others have pointed out, is that the city has no framework with which to strategically coordinate land use changes and infrastructure investments. Without a comprehensive planning process to guide investment decisions and resolve equity tradeoffs, the city’s moves to densify and develop in particular neighborhoods are met with fear and protest.

But also part of the problem is the de Blasio administration’s outdated mindset with respect to development more generally -- particularly development on land owned by the city. The practice of selling publicly-owned sites to developers to raise revenue, and to promote the creation of new, mostly market-rate housing and office inventory, became commonplace under Mayor Michael Bloomberg. The de Blasio administration has continued the practice, frustrating those of us who believe there are better uses for public land.

To take one example: in Long Island City, Queens, a battle is brewing about the fate of two sites in Anable Basin. Located on 44th Drive close to the waterfront, they are currently owned by the public. But they have a history: in 2018, the city’s Economic Development Corporation had issued requests for proposals or requests for expressions of interest for them, and come to a preliminary agreement with the development firm TF Cornerstone to build and operate a mixed-use development (with residential, commercial, and some industrial uses) on one of them. Then came Amazon. Last November, the sites appeared on the map of the planned HQ2 campus.

When the Amazon deal fell through in February of this year, the city went silent, and local activists (many of whom had fought HQ2) started thinking not just about what they didn’t want in their neighborhood but about equity-positive alternatives.

Last summer, a coalition formed around the aim of creating a Community Land Trust (CLT), which provides a vehicle for permanently affordable development managed by mission-driven organizations. The land trust activists developed a plan to renovate one of the city-owned sites – a 638,000 square foot industrial building at 44th Drive and Vernon Boulevard – as a multi-tenant space for small manufacturers, working artists, a commercial kitchen, and a school. A non-profit partner selected to operate the space would be subject to a special deed, drawn up by the land trust, that compels them to charge below-market rent in perpetuity to the kinds of tenants who are currently being displaced from Long Island City in droves by luxury development.

Judging by the YourLIC planning exercise announced last month, the city appears to have other plans for the sites the public owns in Anable Basin. But before things go any further, the de Blasio administration should consider conveying the site at 44th Drive and Vernon Boulevard to the Western Queens Land Trust.

On land it owns, the city should be leading by example, fostering development that creates family-supporting jobs and offers open space and public facilities (like schools) without contributing to gentrification and displacement. An indication of what is possible in Long Island City can be seen on the activists’ website, OURlic.nyc.

We have set the bar too low for too long. Using public land, the city can subsidize development that improves communities without making them unaffordable to the people who currently live there. This path is not the most lucrative option in financial terms. But the highest and best use of land need not always be the use that commands the highest investor return. In Long Island City and elsewhere, conveying city-owned property to land trusts and other mission-driven organizations is an investment in neighborhood value that could help earn back the trust of the currently disenchanted.

***

Laura Wolf-Powers is an associate professor in the Department of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College. On Twitter @wolf_powers.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hidden in Plain Sight: Billions in Potential Revenue for NYCHA

(East Harlem NYCHA superblocks possess massive amounts of unbuilt air and ground space, as illustrated in the HOUSING DENSITY show currently on view at the Skyscraper Museum.)

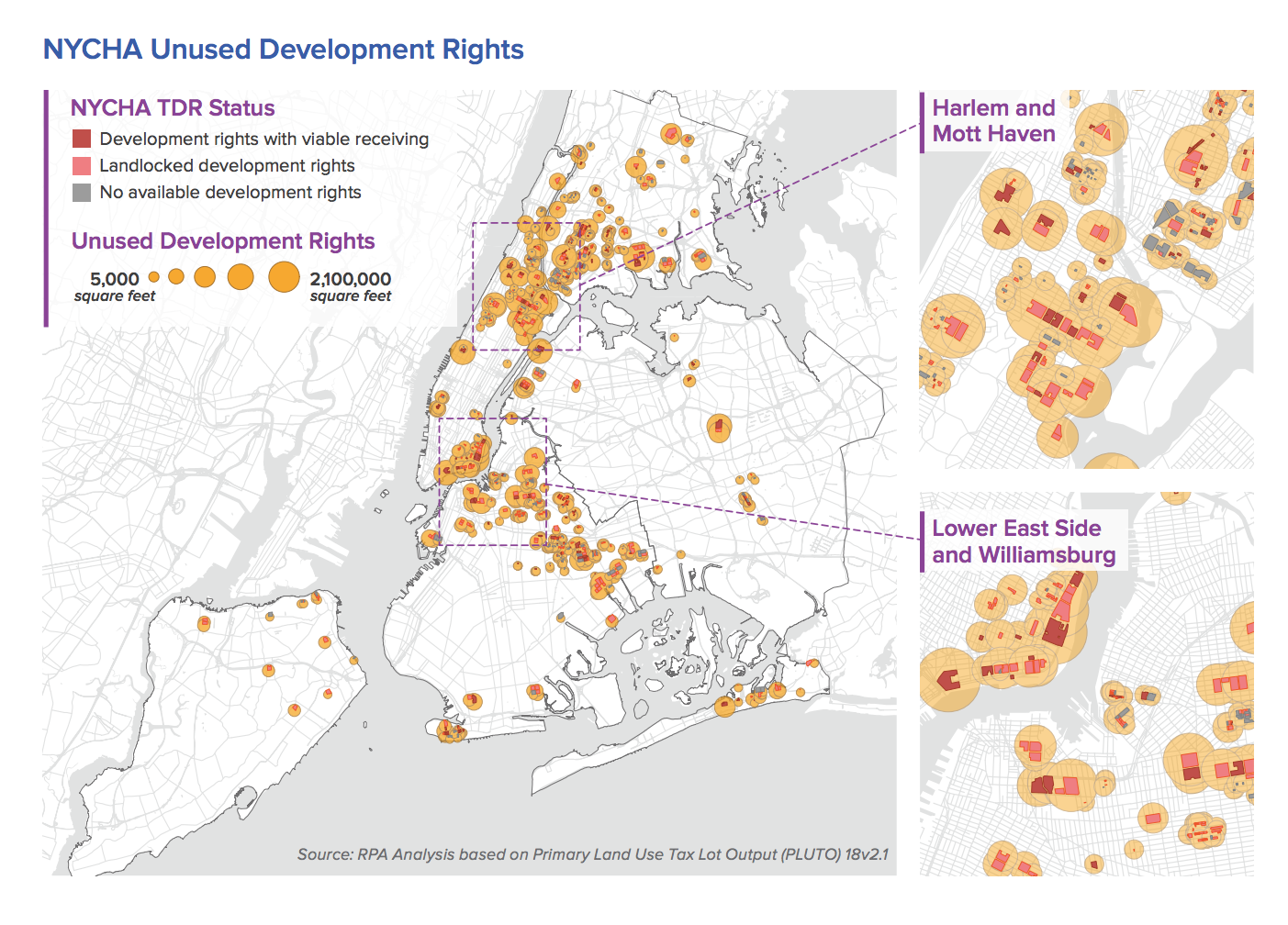

NYCHA developments full of high-rises seem massive from a distance, but on closer examination their visual bulk disguises a deeper truth: they are dominated by open space. What to do with all this unbuilt space has inspired competing and controversial plans for infill and redevelopment. A growing number of policy experts believe that the New York City public housing authority would benefit just as much from a more aggressive program to transfer development rights for cash. They are right.

That NYCHA is “underbuilt” has been known for decades, but the general consensus has been that the rules governing Transferable Development Rights made it impossible for the housing authority to monetize the unbuilt square footage. Large NYCHA superblocks frequently lack adjoining parcels to which these rights could be transferred under current rules. NYCHA, to most eyes, appeared to be landlocked.

Intrepid staff at the Regional Plan Association have now calculated that a straightforward rule change (a city Zoning Text Amendment) could put into play an astounding 78 million square feet of NYCHA’s transferable rights. Selling these rights, they estimate, could yield $4.2 to $8 billion for NYCHA repairs.

The key to unlocking these revenues is to allow the authority more flexibility than typical property owners in moving its Transferable Development Rights around the city. By moving NYCHA air rights across the street, up to a half mile away, or within a Community District, the opportunities for revenue generation increase exponentially.

(Image Courtesy Regional Plan Association, Time to Act)

(Image Courtesy Regional Plan Association, Time to Act)

These eye-popping revenue projections could be game-changing when it comes to paying for much-needed repairs of boilers, apartments, and more.

Relying more on development transfers would also defer a growing number of pitched battles over infill and redevelopment. As illustrated in the HOUSING DENSITY exhibit at the Skyscraper Museum, low-density NYCHA superblocks (even in their rundown state) offer current residents a style of living that is difficult to replicate anywhere else in New York. Where else in the city can you find relatively large apartments (avg. rent $533 per month per apartment) with windows in every room looking out on open space, trees, and the city?

Infilling NYCHA with new structures will not only take away some of the city’s last open spaces, and tree canopy, but will further undermine the remaining quality of life for current NYCHA residents. Less air flow, fewer trees, and reduction in permeable surfaces seems like a bad idea for a warming city. Infill projects are, therefore, stalling out for a good reason. Redevelopment projects of buildings and grounds offer a brighter hope for completely rethinking NYCHA’s midcentury tower-in-the-park formula, but so far the politics of redevelopment are even more fraught than infill.

(Johnson Houses in East Harlem: Just one of many NYCHA developments with extensive tree cover and lawns.)

As with all things NYCHA, a major policy shift on Transferable Development Rights will generate enormous resistance -- but probably not from NYCHA residents. Instead, it will be NYCHA neighbors, some of them blocks away from current projects, who will feel the impact. If this proposal moves forward they will find that many builders can upsize their plans for development. Expect a backlash from non-NYCHA neighborhood activists and those that represent them including city, state, and federal elected officials.

Some say the politics would be too difficult and few city leaders have embraced this brave plan as of yet. There is, however, a double standard here that should be addressed. Politicians found a way, for instance, to make similar changes in East Midtown in the name of commercial modernization. Zoning text changes there enriched a few billionaire property owners, and were achieved over some vocal community objections, so why not make similar changes for the benefit of NYCHA’s 400,000 residents?

It is hard, moreover, to have much empathy for city residents and their elected officials resistant to finding alternative funding sources for NYCHA. It is true that Mayor de Blasio has committed unprecedented local funds to NYCHA, but the City of New York has found much more additional money for generous labor contracts, ferries, new jails, and bike paths, while allowing NYCHA residents to face another winter with very old boilers. If politicians and non-NYCHA residents are unalterably opposed to Regional Plan Association’s proposals, they should at least propose an alternative means of financing the $30+ billion renovations NYCHA needs.

In the meantime, the treasure hidden away in underbuilt NYCHA superblocks should be used as a major downpayment for immediately upgrading resident life.

***

Nicholas Dagen Bloom, Professor of Urban Policy and Planning, Hunter College is author of Public Housing That Worked, How States Shaped Postwar America: State Government and Urban Policy, and a co-curator of the HOUSING DENSITY show.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Commission Failure Shows Need for One True Fix for New York Elections

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Looking at the plan from the state campaign finance commission, anyone who’s had even a passing interest in New York politics is left either scratching their head or gritting their teeth (maybe both). It’s no surprise that the aspects of the commission’s just-completed work that have provoked the most vociferous opposition and passionate debate have nothing whatsoever to do with public campaign financing. On the left and on the right, activists, lawmakers, and good government groups are decrying the elements of the plan that would eventually kill off every minor party in the state and keep other potential new ones from sprouting up.

These recommendations include raising the number of votes necessary to retain ballot access, going from 50,000 to a minimum of 130,000 and making it a biennial rather than quadrennial test. Given recent voting trends, the move would kill off every minor party in the state except one - the Conservative Party. Trust me, as a leader in a political party (the Reform Party) that just lost ballot access under the existing thresholds, I can tell you that getting 50,000 votes is no walk in the park.

Potentially even more alarming, though, is the dramatic increase in the number of signatures necessary to qualify for the ballot statewide, going from 15,000 to 45,000. This increase would reserve ballot access for only the super wealthy or the hand-picked candidates of the political establishment or certain deep-pocketed special interests, very likely keeping new parties from sprouting up (as two did last year to make the ballot: SAM and Libertarian).

If the Legislature allows these new rules to be implemented, it would likely bring an end to New York’s longtime history of having robust and influential minor parties. It’s a tradition that goes back well over a century in our state. So, why do this? Is the public really clamoring for a less crowded ballot with fewer choices? Of course not!

Aside from a scorned governor seeking vengeance on a political rival (Andrew Cuomo and The Working Families Party), there is actually ample reason to think that our current system, where minor party bosses are treated like major power-brokers, doesn’t work well.

We’ve seen time and again over the last half-century example after example of parties with paltry memberships and even smaller vote totals be showered in patronage jobs, direct donations, policy-making roles, and more in exchange for their ballot lines. In some cases fusion voting in this state has produced minor party leaders (baby bosses) who seem like their sole reason for maintaining a party is acquiring of money and patronage, with little regard for anything resembling a coherent legislative agenda.

But to minimize these baby bosses, is it really wise to eliminate the voter options of the Green Party and the Libertarian Party, who rarely cross-endorse major party candidates and provide an important voice for voters that would otherwise be ideologically disenfranchised? No!

Thankfully there is a way to kill off the illegitimate minor parties and their baby bosses without killing of all minor parties and the valuable options they provide to voter: non-partisan elections.

The state Legislature should immediately pursue a shift towards non-partisan elections in order to provide New Yorkers with real choice and competitive, more thoughtful elections. It would work similar to how special elections are run in New York City, and elections in cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and Houston, and even cities here in New York like Watertown and Sherrill.

Here’s the novel concept. Anyone who wants to run for office can run. They’d all run on the same ballot under the same rules -- whether running for Governor, State Assembly, County Executive, etc. There would be no Republican or Democratic line on the ballot, and much to the pleasure of Governor Cuomo, no Working Families Party line (and so on). This would mean that the baby bosses wouldn’t be able to demand a job for their incompetent relatives or demand that candidates buy pricey tables at party fundraisers.

So how does all of this help minor parties and allow voters more choice?

Under a system of nonpartisan elections, without the stigma of running as “third party” or “spoiler” candidates, the candidates of minor parties could actually get broad considered and be elected. If you look at places around the country that have nonpartisan elections, we’ve seen many examples of candidates without the endorsement of either major political party getting elected and in some cases launching high-profile and successful political careers.

These include Jesse Ventura in Brooklyn Park, MN; Dennis Kucinich in Cleveland; Oscar and Carolyn Goodman in Las Vegas and even the current Mayor of San Antonio, Ron Nirenberg. Lest anyone think, though, that nonpartisan elections would suddenly allow the fringes of the political spectrum to have unwarranted access to the levers of statewide policy-making, one should keep in mind that cities like Chicago and Boston have consistently elected establishment politicians, whose major party bonafides are without question.

In discussing a switch to a nonpartisan system of elections, there will be some who protest by saying that seeing a partisan label on the ballot offers voters a clue as to a candidate’s ideological belief system. For those folks, I’d ask: what does seeing both Charles Barron and Dov Hikind running as Democrats from Brooklyn really tell you about their ideology? How about seeing judicial candidates nominated by every party on the ballot?

The bottom line is this: if you want voters to have more choices and minor parties to continue to function, but not corrupt the system, the only real choice is nonpartisan elections for every office across the state.

***

Frank Morano is an activist and radio host. On Twitter @frankmorano.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.