What I’ll Tell My Kids About 9/11

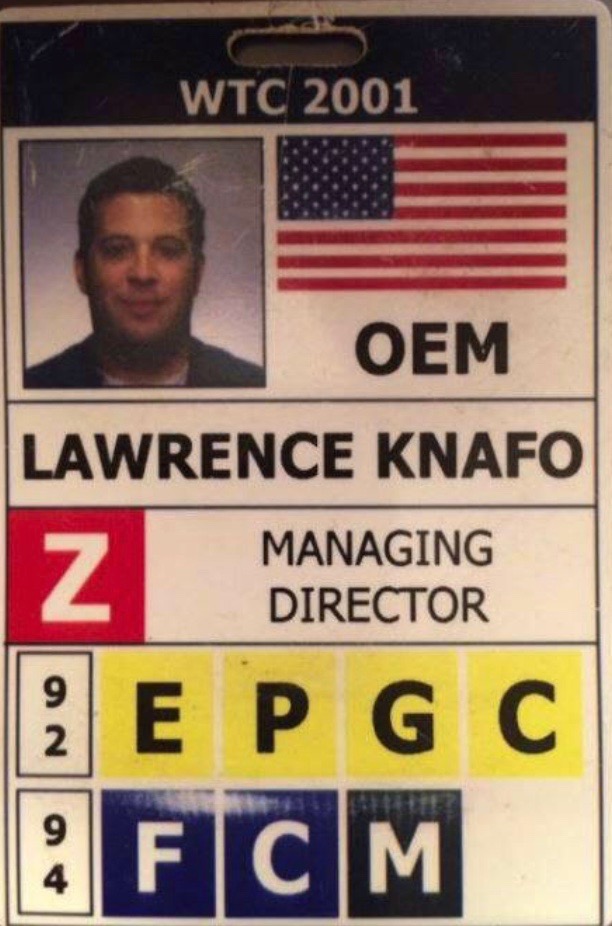

(photo: NYC OEM)

I recently saw the 9/11 inspired Broadway musical “Come From Away.” The show pays tribute to the 9,000 residents of Gander, Newfoundland – a group of ordinary people thrown into an extraordinary situation. Faced with thousands of stranded airline passengers, the people of Gander opened their homes and their hearts to strangers from all walks of life and all religions.

The show was a welcome reminder of the spirit shown by New Yorkers in the days and weeks following 9/11. It brought back memories of New Yorkers lining the streets to cheer on first responders and doing whatever they could to help one another during a surreal moment in our city’s history – a moment when our massive city felt a little more like small town Gander.

As the show brought 9/11 memories vividly back to life, I couldn’t help but note the reaction – or lack of reaction – of many around me. I assume that many in the audience were visiting New York from some faraway place, or perhaps were too young then to now remember that horrific day. While I tried to share in the joy of the musical and the positive story it told, I was struck at the lack of emotion many showed upon being reminded of the horrors of 9/11.

The next morning, I was taking my kids, 5 and 8, out for the day and reflected on the upcoming 9/11 anniversary. I’ve always told them how ground zero is a place that is very special to me but have only shared some of what really happened that day, and little of my personal story.

When my wife asked my son about 9/11, he shared what he knew, but when she pressed for more information, he simply said, “I don’t remember.”

At that moment, I was shaken. I could only wonder if I had failed as a parent. I wondered if I had failed as a New Yorker. And I wondered if I had failed those that made the ultimate sacrifice that day.

My wife insists that our kids are too young to know the details of what really happened, and perhaps she is right. Why ruin the innocence and joy of childhood with the reality of the evil that surrounds us?

But, I couldn’t help but wonder. Should I have told them about the horror that we all experienced that day? Should I have told them how the world changed? Should I have told them my story and how 9/11 forever changed me?

But, I couldn’t help but wonder. Should I have told them about the horror that we all experienced that day? Should I have told them how the world changed? Should I have told them my story and how 9/11 forever changed me?

How else could they learn the importance of remembering the lost. How else could they know to respect the police, the firefighters, and the EMS workers that keep us all safe.

How would they know that sometimes they should run towards danger to help others? And if not that, how else would they know that sometimes all you can do is try to help in whatever way you can – kind of like the people of Gander and all those New Yorkers who lined the streets to cheer on our first responders.

After 9/11, I used to wear a shirt with the logo “Gone, but not forgotten.” I remember every time I would put the shirt on, I would think: how could anyone ever forget.

But when I watched the reactions during “Come From Away,” I started to seriously question whether many had already forgotten - or worse yet, never known.

But it wasn’t until my son uttered those three words, “I don’t remember,” that I fully realized the meaning of “Gone, but not forgotten.”

Remembering 9/11 won’t just happen on its own. We all have a responsibility to share our stories and to teach those around us what happened when terrorists turned airplanes into weapons.

And as I thought about how we could better remember 9/11, I realized that’s exactly what the writers of “Come From Away” had done. They had told the story of 9/11 and in doing so, had helped to preserve our history. They made sure that we remembered those we lost and they helped honor those that did whatever they could to help.

“Come From Away” was also a good reminder that people from nearby as well as those far away suffered during 9/11. It was a reminder that many, many people have their own stories about 9/11. And it was a reminder that we must always tell the fully story of 9/11 – offering different perspectives, sharing the good, and, of course, sharing the bad.

Telling the story of 9/11 forces us to acknowledge the unthinkable things done to innocent people. But it gives us the opportunity to honor the heroes that raced into danger to save innocent lives – many becoming victims themselves. And yes, it allows us to share the stories of how we came together as New Yorkers and how we came together in Gander – wherever your Gander may be.

“Come From Away” helped me realize that there are many ways to tell a story. And with that, perhaps there are many ways to teach our children – to teach my children.

The irony of passing judgment on the “Come From Away” audience is not lost on me – I was quick to judge, but realize that just because the audience enjoyed the show, doesn’t mean they didn’t appreciate the significance of the story.

As a parent, I want to shield my children from life’s unpleasant realities, but I also want to make sure that their values are driven by our history...by my history.

I still don’t know how or when I’ll share the full details of 9/11 with my kids. My wife is probably right (she usually is) when she says they are too young to learn it all.

But while they may not be old enough to learn about terrorism, they are certainly old enough to learn what “Come From Away” reminded me – how love can, and did, conquer evil – in Gander and in New York City.

I’m going to start by teaching them that lesson.

***

Larry Knafo served in the FDNY, was a founding member of the NYC Office of Emergency Management (OEM) and served as the First Deputy Commissioner at the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. After 9/11 he led development of the City’s Family Assistance Center, drove technology recovery efforts, and aided in the development of the City’s Emergency Operations Center.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How ‘Independent’ Must the New York Attorney General Be?

The state Democratic convention (photo: Gotham Gazette)

One thing is for sure about the four candidates in the Democratic primary for Attorney General: each wants to be thought of as “independent.” Witness these self-descriptions:

Leecia Eve: “An independent advocate for all New Yorkers”

Tish James: “I’ve been independent all my life”

Sean Patrick Maloney: “I think I bring true independence”

Zephyr Teachout: “An independent fighter for New York”

This independent streak all intensified when James, endorsed by Governor Andrew Cuomo, prevailed for the party designation at the Democratic state convention. To diminish her resultant electoral advantage, the other three candidates sought to portray her during the primary campaign that followed as dependent upon Cuomo politically and therefore less likely to attack the pervasive corruption in state government, corruption that has reached into the governor’s own office.

It seems logical enough. Unlike most other state department heads in New York, the state attorney general is elected by the voters, not appointed by the governor (thus the claim to be “the people’s lawyer”). Lots of statewide elected offices were eliminated or converted to appointed through constitutional change over the last century and a half. Meanwhile, the attorney general remained elected. There must be some rationale, people reasoned, for persisting in this way over all those constitutional conventions. Assuring the office’s independence seemed an explanation that fit the bill.

But independence for what?

New York’s constitution is almost entirely silent on the attorney general’s job. Its powers are rooted in common law and further specified in statute. Chief prosecutor is not among them. There are some exceptions, but since the early 19th century criminal prosecution has almost always been the work of locally elected district attorneys. Read the candidates’ own campaign literature. Mostly they are not promising to prosecute corruption in Albany using powers the office has now; they are promising to seek constitutional and legal changes that would give them the powers to do this.

Then there’s the attorney general bread and butter: representing the executive branch of state government in court and advising state agencies on legal matters. Attorneys general who aspire to be governor (all of them, lately) may use their independence to decline to represent the state when they differ from the governor on policy, as was the case at times for Robert Abrams during the administrations of Governors Hugh Carey and Mario Cuomo. This caused the first Governor Cuomo to exclaim: “No candy store can be run this way. You have this massive operation called an attorney general but you can never tell when he will be willing to represent you.”

Interestingly, Eliot Spitzer as attorney general did just the opposite. At some political risk, he felt obligated to represent the state in court in defense of its then-ban on same-sex marriage even though he opposed this ban as a matter of state policy. But the point is this: “independence” may be a convenient excuse for the attorney general to decide not to do his or her job for personal or political reasons. Yet the state still must be represented; if the attorney general steps away, other lawyers must be hired to do the work.

Most New York attorneys general returned to relative obscurity after their time in office. Of the 56 who’ve served, two of the three with recognizable names (at least to the political cognoscenti) prior to the current era were attorneys general before the office was elective: Aaron Burr, later vice-president, and Martin Van Buren, later president. The third was Jacob Javits, the longtime U.S. Senator.

The office became a stepping stone to the governorship only lately, after Spitzer rediscovered the attorney general’s extensive powers under the Martin Act, passed in 1921 to counter rampant securities fraud. Because New York is an international financial capital, the state’s AG is uniquely situated to be a major player in policing the national economy. Here’s one place where independence does count. Spitzer’s aggressive pursuit of abuses by big Wall Street brokerage houses and investment banks under the Martin Act, followed by Andrew Cuomo’s and Eric Schneiderman’s after him, made the New York attorney general a nationally important figure.

Because Donald Trump is a New Yorker, the state’s attorney general is also uniquely situated among his or her peers to hold Trump accountable for his pre-presidential personal and professional financial practices. One result is the current lawsuit seeking the dissolution of the Trump Foundation for persistent illegal practices over at least a decade.

A strength of the American federal system is that it always provides a base of power in some states for the party out of power in Washington, D.C. Those who designed this system could not have imagined the complexity of our current intergovernmental federal arrangements, nor the degree to which public policy is now decided in the courts. Modern federalism has been further transformed through the use of these courts by state attorneys general to advance policy agendas.

Here again independence is key. State attorneys general of the party out of power in Washington have again and again joined in collaborative class action suites to challenge national policy and its implementation. Republicans sought to undo Obamacare, and are still at it. Democrats, with the New York attorney general in the lead, continue to litigate to block Trump administration actions on such issues as immigration and environmental regulation.

So as we New Yorkers choose an attorney general this year, we must be mindful that we are choosing a national leader to fight for New Yorkers on the key questions that face the state and the nation.

And also that we are picking a likely future candidate for governor.

As we do this we are already sure to make history, if only because every major candidate, including the Republican, Keith Wofford, is in a class protected by law against discrimination -- female, African-American, gay – from which we have not yet elected a person to hold either of these statewide offices of governor and attorney general. (Governor David Paterson, who is African-American, was not elected, but gained office by succession from the office of Lieutenant Governor after Spitzer’s resignation.)

But we need something more. We need an attorney general who makes history not just by who he or she is, but through doing the job -- with passion, energy, and the right balance of collaboration with and independence from the governor.

Don’t forget to vote.

***

Gerald Benjamin is director of The Benjamin Center at SUNY New Paltz.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Path to Reduce Building Energy While Preserving Affordable Housing

photo via the Urban Green Council

When it comes to combating climate change, the stakes have never been higher. The Trump administration’s failure to address this crisis means progressive urban leaders must do much more to reduce carbon emissions – especially in large apartment buildings that contribute so heavily to climate change.

One of the greatest challenges to addressing carbon emissions in residential buildings is ensuring that crucial energy efficiency upgrades don’t trigger rent hikes for low- and middle-income tenants living in rent-stabilized apartments. Rent-stabilized units account for a significant percent of large multifamily building space, so it is important to find a way to address this situation.

The good news is that we and dozens of other organizations have joined forces on a new proposal that would tackle this challenge – among others – by reducing carbon emissions at 50,000 New York City buildings while providing a plan to avoid hitting rent-stabilized tenants with the bill.

The new Blueprint for Efficiency by the Urban Green Council’s 80x50 Buildings Partnership – of which we and other organizations in the Climate Works for All Coalition are members – lays out a roadmap for cutting large building energy use by 2050.

As the Blueprint notes, city and state law currently allow the cost of many “major capital improvements” (MCIs) – including some efficiency measures like boiler replacements – to be passed on to tenants in rent-stabilized apartments. These costs then become permanent rent increases. They can also push units toward deregulation: above a set rent threshold, the units are forced out of stabilization. For too many tenants, MCIs mean higher rents they can’t afford, or even losing an apartment for tenants who are already stretched to the limit, rather than benefiting from lower energy bills and a healthier, better-maintained home. Additionally, taking apartments out of rent stabilization reduces the affordability of our housing overall.

So as part of this proposal, we are recommending new rules promoting low-cost, energy-saving measures for the rent-stabilized sector that do not qualify as MCIs, and oversight to ensure that if measures cause rental increases, action is taken to change the rules. We also believe there should be support and incentives provided so that the rent-stabilized sector can achieve the same kind of efficiency gains as market-rate buildings.

This kind of approach allows us to achieve significant energy reduction goals across the board, while protecting rent-stabilized tenants at every turn.

Beyond the rent-stabilized market, affordable housing owners and nonprofits often face thin margins and financing challenges, so efficiency upgrades are rarely a priority. The Blueprint recommends helping them through greatly expanded support programs, incentives, improved access to financing, and coordination with state-level programs that help reduce energy use.

Working with stakeholders who don’t often find themselves in the same room together we came up with these recommendations based on robust discussion and consensus-building.

Alongside all the Buildings Partnership members, we look forward to working as quickly as possible with the City Council and the de Blasio administration to translate our broader proposal into new legislation that can be advanced this year.

This would be a real win-win for all New Yorkers who care about combating climate change and preserving affordable housing across our city.

***

Maritza Silva-Farrell is Executive Director of ALIGN: The Alliance for a Greater New York & Stephan Edel is Director of New York Working Families. On Twitter @MaritzaSf and @GreenJobsNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.