Albany Must Keep the Charter Cap

Council Member Dromm, the author, with his IDNYC (photo: William Alatriste)

Earlier this year, the New York City Council passed my resolution urging the state legislature to keep the cap on charter schools. That was nothing new: Council Members have long showed their opposition to raising the cap. But, with recent efforts by powerful special interests, including more than $13 million spent in lobbying and campaign ads, we need to remind New York why raising the cap is not only unnecessary, but also harmful to our public school children.

First, there is the capacity question. Charter schools have 2,500 unfilled seats in New York City. In addition, current charter agreements could allow for more than 27,000 additional authorized seats. In other words, these charter schools already are not handling their assigned share of students, and that burdens crowded public schools, making it more difficult for those schools to provide quality education.

Second, charter schools are not required to serve students who transfer to or join schools mid-year because of disciplinary measures or because of a family's choice. They also do not serve nearly the same amount of students with special needs as public schools. This means that when the school year starts, charters receive funding for a certain number of students yet actually end up teaching fewer than they are budgeted for. They then pocket the remainder and can boast lower class sizes while public schools again shoulder the burden.

Finally, the Center for Popular Democracy reported that New York stood to lose over $54 million to charter school-related fraud in 2014 alone. Audits can help uncover instances of fraud, mishandling of funds, conflicts of interest within governing boards, and a number of other troubling findings, yet charter schools largely oppose efforts to increase transparency. The State Comptroller's attempt to audit charter schools has already been foiled at every turn, meaning New Yorkers are left in the dark about how exactly our public dollars are spent.

Meanwhile, more than $5 billion in state money is owed to our traditional public schools to provide every child access to a "sound basic education" per the Campaign for Fiscal Equity ruling. Forty-four percent of all schools in New York City are overcrowded. The City's Independent Budget Office reports that most schools are at 102 percent capacity or more, and 88 percent of the city's charter schools are co-located within a district school, adding to the space crunch.

Co-located charter schools, by the way, are an exercise in inequality: privately run schools, with access to both private and public funds, that are taking resources from underfunded district schools. What does this mean for the social climate in these schools? Many students feel, and rightfully so, that district schools and their students are not valued the way they should be.

It is sensible to provide the money and attention owed to our public schools to keep them strong. Charter schools already divert resources from the majority of students, who attend public schools. Charter schools do not serve our children, especially the most needy, with enough accountability to justify increasing their share of funding.

All children deserve an education system that celebrates their potential by giving them the space and funding necessary to achieve educational excellence. The raising of the charter cap would be damaging to our public school system in terms of morale, space, funding, and overall quality. Leaders in Albany should finish their legislative session without altering the cap. Instead, it is time to ensure a feasible means of success for public schools by giving them the focus they need and not investing in a private enterprise that has yet to fulfill its promise to New Yorkers.

***

Daniel Dromm is the Education Committee Chair of the New York City Council.

MTA Success, Challenges Necessitate Cooperation on New Capital Plan

MTA work (photo: Metropolitan Transportation Authority / Patrick Cashin)

There is general agreement among New Yorkers that something must be done about the city’s transit system. Both MTA president Thomas Prendergast and Straphangers’ Campaign staff attorney Gene Russianoff have raised the specter of the state of chaos and disrepair into which the system fell in the 1970s and 1980s as a possibility, should the political echelon not get its act together.

Yet the challenges that the MTA faces today are far different from those of decades past. Ridership is surging, not falling, and the stress from which the system suffers is a result of crowding and rapidly rising demand, not popular neglect and apathy towards the urban world. And just as the problems of today are different from the problems of yesteryear, so too will the solutions need to be. Though primary responsibility for the MTA’s fiscal and managerial wellbeing ultimately rests with its legislative supervisors in Albany, fixing the challenges facing the agency today will require complex, nuanced cooperation between stakeholders at all levels of government and civic leadership.

The MTA’s recent success cannot be overstated. Ridership on the New York City subways—the MTA’s most popular, and core, service—reached the highest level in 65 years in 2014, with growth seen across all boroughs and lines. And ridership growth continues to expand outside the traditional peak hours, setting records for off-peak and weekend ridership. Despite—in fact, to some extent, because of—this success, the system faces a cascade of new challenges resulting from its antiquated infrastructure and from overcrowding.

2014, and its record ridership, also saw a significant rise in delayed and disrupted trains, with about 20 percent of all trains arriving late. At the same time, MTA bus ridership has fallen significantly over the last five years after major service reductions in 2010. And work persists on the subway tunnels and on South Ferry station damaged by Superstorm Sandy, demonstrating the system’s significant need to build resilience.

Rehabilitating the MTA system and modernizing it to meet the 21st century demands that have hit it so hard require demonstrated commitment from all involved, and that starts with working out an agreement on the 2015-2019 MTA Capital Plan. And right now, it doesn’t look good.

The MTA can certainly help itself by accelerating state-of-good-repair investment (things like advanced signaling systems, new train cars, and track work) that would make the rides of everyday commuters speedier and more reliable. It should communicate better the importance of these maintenance investments and practices to riders, and the economic impact of capital and maintenance investments alike to upstate voters and politicians. And it must show the public and political leadership that it is able to manage projects efficiently and cost-effectively, particularly as major investments like the Second Avenue Subway, LIRR East Side Access, and Metro-North Penn Station Access move toward completion in the coming years. Avoiding embarrassments like the ever-delayed opening of the (essentially complete) 7 line extension would be a good start.

Ultimately, though, responsibility for making sure the MTA gets the investment—and the oversight—it needs rests with the political echelon both in New York City and in Albany. Though the Cuomo administration has professed a significant emphasis on resilience and recovery from severe weather across the state, it has shown little interest in helping guide money to the MTA that would help build the system’s capacity to resist and recover from future damage. The MTA’s status as a state-level authority has also isolated it from its most important constituency, and New York City’s contribution has lagged well below what would be expected given inflation; had it kept pace, it would have been $363 million last year, rather than an average of $100 million since 2000.

Coming to a consensus on how to fund the MTA capital plan, and on improving the system generally, will require a degree of seriousness and recognition of technical and fiscal constraints from city and state officials that many have yet to demonstrate. The MTA system is at a precipice, staring over a cliff at the process by which dysfunctional governance can debilitate a transit system, the effects of which can be seen not far away. As a result of what some have called “budget chicken” between DC, Maryland, Virginia, and the federal government, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority has now entered a self-reinforcing cycle of deferred maintenance, service cuts, and degraded user experience that transit professionals call a “death spiral.” That future—a game of cat-and-mouse between legislators, the executive branch, and local politicians, leading to a service crisis—could be the outcome in the MTA service region if those responsible for the needs of the system do not prioritize its wellbeing.

***

Sandy Johnston is a student in the Master’s in Regional Planning Program at the University at Albany and a graduate of Columbia University and the Jewish Theological Seminary in Manhattan. He blogs at www.itineranturbanist.wordpress.com and is on Twitter at @sandypsj. He is an intern for the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a non-profit organization working toward a more balanced, transit-friendly and equitable transportation system in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut.

Say No to The Media Hype

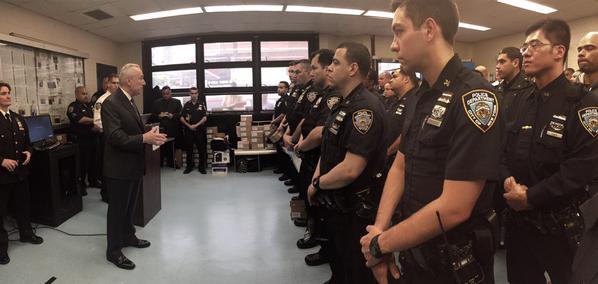

NYPD (photo via @CommissBratton)

In recent days our city's leading tabloid newspapers, The Daily News and The Post, published screaming headlines and overheated stories promoting the dubious notion that the uptick this year in homicides - as compared to a similar period in 2014 - is directly tied to the NYPD's reduced use of the discredited stop-and-frisk tactic. This fear-monghering ignores important realities.

Some actual facts, based on the police department's own data, that challenge the wisdom of that argument and that provide an instructive and somewhat longer view about what is really happening on New York City's streets: