Dancing in the Park

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

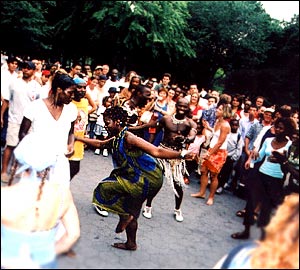

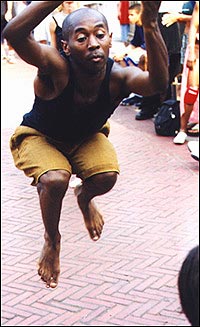

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

I usually enter through a gateway of benches at West 110th Street and roll on my inline skates past picnickers, tennis courts, the castle and the Boathouse Café. Every year, I promise myself a detour for a pick-up game of volleyball in the worn grass across from the reservoir. But instead, every weekend, my destination is always the same -- the African Drum and Dance Circle near the Band shell.

I was intimidated when I first encountered the African drummers in Central Park six years ago. The music and faces were different. They were from Senegal, Mali and Ghana. The circle made me wonder if I was out of touch with who and what I was as an African-American. The beat touched a primal nerve, reverberating in the torso, echoing in the ears, and I couldn’t help dancing on my skates to the drums. I did not know how the drummers would react, or what I would say or do if they said something to me.

Now I feel at home dancing in the drum circle. I have bonded with the African drummers and the other members of the circle, through languages, cultures, incense and comfort zones that intermingle and in some instances collide there.

The music beckons passersby from all corners of the park. It is a legal intoxicant that causes foot-tapping, finger-snapping, hip-swaying and losing track of the time. The drum circle lowers inhibitions as people cross ethnic, religious and economic boundaries and dance. There is no need for red tape, velvet ropes or government polices. The circle is its own world. The only rule is to enjoy. Flailing of bodies, heavy breathing, and sweating is encouraged.

There is no special training or equipment needed to dance in the center or off to the side. It is

as simple as taking a deep breath, smiling and stepping back into the enclosed area. The drum circle is a family of brothers and sisters who aren’t keen on parental figures. The aim is unity without a pecking order. There is harmony among the core drummers

and dancers, yet there are periodic challenges from outsiders seeking to strike a sour note.

There is no special training or equipment needed to dance in the center or off to the side. It is

as simple as taking a deep breath, smiling and stepping back into the enclosed area. The drum circle is a family of brothers and sisters who aren’t keen on parental figures. The aim is unity without a pecking order. There is harmony among the core drummers

and dancers, yet there are periodic challenges from outsiders seeking to strike a sour note.

Prior to dancing with the drum circle, I can’t recall a time when I was airborne without being on an airplane or tossed in the air by an older cousin. The drum circle was the first time I was compared to a puppet without its strings, or having coils in my legs instead of bones.

I leave the circle physically exhausted, yet looking forward to the next weekend. Central Park and the circle have kept me happy and alive.

Kendall Williams is a freelance writer, editor and English as a Second Language tutor.

The Manhattan Waterfront Greenway -- A Thin Green Line

When the Manhattan waterfront greenway opens in just a few weeks Mayor Michael Bloomberg will have achieved what 25 years of planners and policymakers could not: a nearly continuous waterfront esplanade (in pdf format) for walkers, cyclists, joggers, skaters, birdwatchers and many others in the world's most famous borough.

With this esplanade the mayor will have wiped away more than two decades of attention deficit disorder that plagued previous administrations, but the key to harnessing the waterfront to benefit the long-term growth of the city lies well beyond this thin green line. Here’s why:

Popular visions for the waterfront of the future generally swing between two extremes. The first is the sweeping green ring around the water’s edge in places like Little Neck Bay, East River Park, or along the Shore Parkway. The second vision of the waterfront is the “Gold Coast” model, where the remnants of industry are replaced with glistening towers in glass and steel.

Each of these models falls short in certain respects. One, the ribbons of green were in reality little more than decorative trim, a green lace edge alongside the massive investment of waterfront highways and parkways which themselves really cut communities off from the waterfront. The development of Hudson River Park is the most recent version of this thin green edge. The “Gold Coast” model similarly falls short as a community development tool because it generally only accommodates the high-end of the income spectrum. Herein lies the Catch-22 for post-industrial waterfront revitalization: can new life be brought to the waterfront in ways that accommodate all city-dwellers as residents and users, or will this new investment physically and economically exclude most people in favor or higher income brackets?

The city’s rezoning proposal for the waterfront of Greenpoint and Williamsburg will test this limit, and largely determine whether those casually referred to in the popular media as “inner-city” dwellers will in fact be relegated to literally inner city districts laden with asphalt and stricken with highways, or whether the city's emerging vision of a new waterfront will serve poor folks too.

One of the problems with a continuous ribbon of green is that it defies the reality that we are a city of islands. As such, we should be embracing modes of transportation that harness the waterways. In Manhattan, the city is making great efforts to expand ferry transit, with a slew of new or upgraded terminals ring the island from East 90th Street south around the Battery and north to West 38th Street (all connected by the greenway). There are efforts afoot to improve or expand landing facilities further north along the west side even as far north as Dyckman Street. But in addition to the city’s need to create new options for white collar commuters, there is a tremendous need to improve the movement of goods in and through Manhattan, home to two of the three largest central business districts in the city.

When the trend toward containerization carried the port to New Jersey nearly a half century ago, it inevitably took a lot of manufacturing and distribution facilities with it. All of these activities continued the seemingly irreversible trend towards highway and truck transport. Since that time, as traffic has increased exponentially, no new freight connections have been created. Getting a truckload of computers or foodstuffs from New Jersey to Brooklyn relies wholly on the same bridges and tunnels that existed back in the Great Depression more than 70 years ago. And Canal Street sure shows it!

While the Manhattan waterfront greenway celebrates the fact that we are an island, it doesn’t help us address the fact that in the grand scheme of highway-dependent economics Manhattan is nothing more than a congested through route to I-95, the Cross Bronx, or the Long Island Expressway. Yes, pedestrians, cyclists, and birdwatchers vote, but it’s the tens of thousands of trucks passing through Manhattan each day that are literally and figuratively paying the freight. Just as the first layer of asphalt on this new path is being laid, neighborhoods such as Washington Heights and Chinatown are still suffering the effects of noise, vibration, and air pollution of this perpetual truck dependency.

One of the greatest benefits of the greenway plan is that it will connect activity and opportunity that already exist at the water’s edge. Fort Washington, the Battery, Stuyvesant Cove and Harlem River Park will be linked to Riverbank and Hudson River State Park as well as dozens of other attractions. Surely every waterfront neighborhood needs such green destinations at the blue water’s edge, but the city also needs places for less-appreciated activities such as the transport of garbage or generation of energy. The pending sale of the Waterside Generating Station by Con Ed, for instance, has already placed pressure on the Lower East Side by causing the expansion of the East River Generating Station. The development of Hudson River and Riverside South parks on the West Side are only creating added pressure to relocate facilities such as the 59th Street marine transfer station which moves thousands of tons of recyclable paper every day. These facilities shouldn’t be closed, they should just be engineered to perform better. In reality, Lower Manhattan probably needs a state of the art marine transfer station far more than it needs more luxury housing.

Perhaps the greatest legacy of the Manhattan waterfront greenway will not be the greenway itself, but the chain reaction of land-use pressures that heat up on the waterfronts of the Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn. Now that Mayor Bloomberg has vanquished twenty five years of inaction for Manhattan, let’s hope he puts forth ambitious and positive plans for waterfronts of the opposite shores that have been abused or ignored for even longer.

Carter Craft, an urban planner, is program director of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance.

Van Cortlandt Park And The Filtration Plant

In a close early-morning vote just before the end of the legislative session, New York State lawmakers approved the use of a section of Van Cortlandt Park for a controversial water filtration plant. In doing so, they broke a long tradition of going against the wishes of the legislator representing an area -- in this case, Assemblymember Jeffrey Dinowitz -- in turning parkland over for a non-park use. If Governor George Pataki signs the bill, it will put in motion a deal worked out between the Bloomberg administration and Bronx politicians to build the $1 to 2 billion facility underneath the park's Mosholu Golf Course in exchange for $243 million of park improvements in the Bronx.

The bill the legislature passed will not permit construction of the plant until the city completes a supplemental environmental impact statement on siting and running the facility in the park, which is like closing the barn door after the horses have escaped. The review is highly unlikely to conclude that two possible alternative sites would be preferable, although it may lead to better mitigation at the Van Cortlandt site. It would not consider a fourth site Assemblymember Dinowitz recently proposed, under the Major Deegan Highway in his district.

The law also requires the city to issue a Memorandum of Understanding, ratified by the City Council, identifying how much money will be dedicated by the city to "acquire and/or improve" Bronx parks and providing a list of eligible projects.

The city is under a court order to filter the part of its water supply coming from the Croton Reservoir to assure the safety of the drinking water. The city's first attempt to build a filtration plant partly underground in the park, proposed during the Giuliani administration, was derailed when the State Court of Appeals ruled that removing parkland from the public, even temporarily, amounted to a taking of parkland that required state legislative approval.

Under the revised plan by the Department of Environmental Protection, the filtration plant would be smaller and completely underground. As in the original plan, the golf course driving range would close during construction and be rebuilt on top of the plant, although plant opponents question whether this would be possible given the security concerns that have arisen since 9/ll. The golf course would continue to operate during construction, but would displace the open space used by the nearby community.

Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe said that the plan would provide "the greatest renaissance in Bronx parks since the WPA in the 1930s." He said that the parks department has a long list of projects that could be funded, including ballfields, playgrounds, and greenways, and will be seeking ideas from Bronx communities.

Organized labor has vigorously supported the siting of the facility in the park, although only about 5 to 15 percent of the various union members live in the Bronx and the legislation does not mandate that construction jobs go to city residents.

People who live in the neighborhood near the site, a low-income, ethnically mixed community, are still vehemently opposed to the plan because of the traffic, noise, and pollution that would be generated during construction and the years-long loss of parkland and of a popular after-school golf program. They are also concerned about additional truck traffic and the transport of chemicals to the plant when it is in operation. The communities near the park have had greatly increasing asthma rates in recent years.

Park advocates are concerned about the precedent of taking parkland for an industrial facility, and say that the enviromental "review" as well as a city land use review - should have been conducted first to determine whether the park is truly the best site, and not just the easiest and least expensive one. "Parks are always the cheapest sites if you think of them as free land," said Elizabeth Cooke Levy, president of the non-profit Friends of Van Cortlandt Park.

The advocates are also leery because the city has not yet released detailed plans for the facility and has made no written guarantees about the amount of money promised for Bronx parks and what projects would be included. Cooke said that she thought the parks department is "naive in believing they're going to control how the $200 million is spent."

Groups concerned about development in the Croton watershed question the necessity of building the plant at all, saying that the city should focus on watershed protection or look at newer technologies. They predict that filtering the Croton water would undermine efforts to protect the water at its source. Three major environmental groups had independent experts review the Department of Environmental Protection studies, and concluded that both filtration and watershed were necessary to safeguard the city's water supply.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.