Shouldn’t Statewide Elected Offices be Held by People Who Are Elected?

Gov. Hochul & then-Lt. Gov. Benjamin (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Office of the Governor)

It is not unreasonable to assume that our six incumbent statewide elected officials first got their current jobs by being elected to them. Not unreasonable, but mostly not so.

Actually, four of the six incumbents in these jobs – Governor Kathy Hochul; recently-resigned Lieutenant Governor Brian Benjamin; Comptroller Tom DiNapoli; and U.S. Senator Kirstin Gillibrand —first came to serve in their roles through the operation of provisions in law for filling vacancies due to resignation, death, or removal for cause.*

Moreover, even though the state constitution requires that no person filling a vacancy in elective office shall hold his or her appointment “longer than the commencement of the political year next succeeding the first annual election after the happening of the vacancy”…three of these four officials (Senator Gillibrand excepted) have served or were selected to serve out the entirety of the term to which their predecessors were elected (Article XIII §3). And now we again face the prospect of using a vacancy-filling process to fill a statewide office, for Lieutenant Governor, this time in the midst of an election campaign.

What’s going on here?

Governor

Article XX of New York State’s 1776 constitution provided that “...in case of the impeachment of the governor, or his removal from office, death, resignation, or absence from the state, the lieutenant-governor shall exercise all the power and authority appertaining to the office of governor until another be chosen…” This provision was retained in the updated 1821 constitution. But language adopted at the 1846 constitutional convention, and still in force, provided that upon succession “…the powers and duties of the office shall devolve upon the lieutenant governor for the residue of the term, or until the disability shall cease.” (Article IV §6).

Thus when Governor Andrew Cuomo resigned on August 24, 2021, Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul became governor and will serve as such for the one year and 128 days remaining of Cuomo’s four-year term (barring removal, death, or resignation).

Lieutenant Governor

New York’s four state constitutions and statutes pursuant to them have all been silent on whether and how to fill vacancies that arise in the lieutenant governorship. Beginning with the succession of Lieutenant Governor John Taylor after Governor Daniel Thompkins was elected Vice President of the United States in 1817, the practice was established of leaving the office vacant, with its duties performed by the Temporary President of the State Senate, and devolving sequentially if necessary to others in a line of succession specified by statute.

In 2009 Lieutenant Governor David Paterson succeeded Governor Elliot Spitzer. Faced with a chaotic political situation in the Legislature, a daunting budget crisis, and a potential scandal in his own office, Paterson appointed Richard Ravitch to serve as Lieutenant Governor under the general provisions of the Public Officers Law. The governor’s action was subsequently found constitutional by the state’s high court, the Court of Appeals.

In accordance with this precedent, Lieutenant Governor Brian Benjamin was appointed by Governor Hochul on August 26, 2021. Though Benjamin was intended to serve out the remainder of Hochul’s term — as the state constitution provides that “No election of a lieutenant-governor shall be had…except at the time of electing a governor” — his resignation in the midst of a campaign finance scandal has again opened the office to be filled by gubernatorial appointment.

U.S. Senator

The 17th amendment to the United States constitution provides that the “executive authority” of each state, if authorized by that state’s legislature, may temporarily appoint a U.S. senator in the event of a vacancy”…until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct. In New York, the governor is given this power of temporary appointment.

In June of 1949 Democrat Robert F. Wagner resigned from the U.S. Senate. Two weeks later Republican John Foster Dulles was appointed by Republican Governor Tom Dewey to replace him. Since the outset of popular elections of U.S. Senators, New York law requires that “…vacancy… [elections were]… to be held at the next annual November general election which occurred at least 30 days after the vacancy arose.” In a special election held in 1949 on the next following general election day, former Governor Herbert Lehman defeated Dulles and took the seat by a vote of 2,582,438 to 2,384,819.

Lehman’s winning margin was provided by the Liberal Party’s cross endorsement. Republicans were convinced that the simultaneity of the special election for the Senate seat with that year’s mayoral election in Democrat-dominated New York City elevated turnout there, also contributing significantly to Dulles’ loss. In 1951 the Republican-controlled state government amended the Public Officers Law so that thereafter persons appointed to fill U.S. Senate vacancies would serve “… until a replacement can be elected at the next congressional election,” removing the possibility of election to fill vacancies in odd numbered years.

Currently, the Public Officers Law specifies 60 days before the primary date in each even-numbered year as the cutoff for determining whether the election will take place that year at the general election or whether it must await the next congressional election.

Kirsten Gillibrand was appointed on January 26, 2009 to fill the vacant U.S. Senate seat created by the resignation of Senator Hillary Clinton when she became U.S. Secretary of State in the Obama administration. There was no congressional election in 2009. Senator Gillibrand served as an appointee until winning a special election on the general election day held in November 2010 to complete the remaining two years of Clinton’s six-year term. She has since been elected twice to full six-year terms.

Comptroller and Attorney General

It was not until the 1846 constitutional convention that popular election was adopted for filling these two and nine other statewide posts. Previously these officials were appointed, under New York’s first constitution by a Council of Appointment and its second (after 1821) by the Legislature. During the time that the appointing power was with the legislature, so was the power to fill vacancies.

The democratizing 1846 constitutional convention also adopted the principle that vacancies in these newly elective offices be filled as soon as practicable by election, and with language that, as noted, persists in New York’s current constitution, that “…no person appointed to fill a vacancy shall hold his office by virtue of such appointment longer than the commencement of the political year next succeeding the first annual election after the happening of the vacancy.”

Within this context, the Legislature sought to preserve what it could of the vacancy-filling power by statute. But legislative sessions were very brief in the 19th century, statewide officials’ terms of office were short (mostly two years), and these were key jobs both for the party patronage and the administration of state government. To assure that they were filled in a timely manner if the Legislature was not in session, therefore, a statute was adopted in 1849 that provided for interim gubernatorial appointment of “some suitable person” to fill vacancies in these positions until “the commencement of the political year next succeeding the first annual election” was adopted, while leaving with the Legislature final authority for making these appointments or making others when it reconvened.

Over the ensuing decades constitutional reforms reduced the number of New York’s statewide elected officials. As a matter of actual practice, power to fill vacancies in the positions of Comptroller and Attorney General came increasingly to reside with the Governor. Parallel to earlier statutory action taken regarding filing vacancies in the U.S. Senate, in 1953 Republican Governor Thomas Dewey proposed to the Legislature constitutional amendments requiring election of the Governor and the Lieutenant Governor on one ballot, barring elections for Comptroller and Attorney General except in (even numbered) gubernatorial election years, and empowering the Governor to fill vacancies in these two statewide officials by appointment.**

These were to be presented to the voters at referendum in a single question. But regarding vacancy-filling, instead of gubernatorial appointment the Legislature presented and the voters passed an amendment that delegated to the Legislature itself the task of establishing a vacancy-filling process for these offices. Then it adopted a law returning to the use of the practice of legislative appointment. The combined effect of this change and the bar on elections for Comptroller and Attorney General except in gubernatorial years was that appointees could serve in these elective offices for the entire remainder of the term to which the departing incumbent was elected.

The New York state constitution currently directs the Legislature to provide by law for filling vacancies in the positions of Comptroller and Attorney General. The process that it specified requires the Legislature to meet in joint session and elect persons to these offices if a vacancy occurs.

State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli was elected on February 7, 2007 by such a joint session to serve the remaining three years and 319 days of the four-year term of Comptroller Alan Hevesi. Hevesi, who was just reelected the previous November to a second term, resigned in December of 2006 as part of a plea bargain in a case involving his unlawful employment of state workers for personal purposes. DiNapoli has since been elected Comptroller three times.

Recent Proposals

Legislation has been periodically introduced and reform suggested to democratize New York State’s processes for filling vacancies in statewide elective office. In his constitutional history of New York, published in 1995, Peter Galie noted that constitutional amendments had received the first of two required passages in separate sessions of the Senate and Assembly “…which would eliminate the power of the state legislature to provide for the filing of vacancies and would delete the prohibition that no election for…[Comptroller or Attorney General]…shall be held except at the time of electing the governor.”

In 2010 the New York City Bar Association Committee on Elections called for a return to historic practice, with elections to fill U.S. Senate vacancies still held on the general election day, but possible in both even and odd numbered years. The Governor would retain the power to appoint an interim Senator, but the elected Senator would enter office earlier, “…upon the issuance of a certificate of election.”

Legislation first entered in 2007, and proposed again in the current session (bill A0596/S03876) by Democratic Assemblymember Kevin Cahill and Republican Senator Joseph Griffo, requires the Governor to call a special election to fill Comptroller and Attorney General vacancies. In a parallel bill (A00708/S03781), Cahill and Griffo do not require the Governor to call a special election, but allow him or her the discretion to do so for these two offices and United States Senator.

A version most recently introduced by Assemblymember Steve Hawler and Senator George Borrello (bill A06297/S03875), both Republicans, leaves initial responsibility for filling vacancies in the offices of Comptroller and Attorney General with the Legislature, but requires election to follow on the first general election day at least three months after the vacancy occurs.

Finally, regarding the lieutenant governorship, Republican Assemblyman Michael Tannousis and Democratic Senator Neil Breslin — on the model of the U.S Constitution’s 25th amendment process for filling a vacancy in the vice presidency — would condition appointment to fill a vacancy on the provision of advice and consent by both legislative houses (bill A08243/S2503).

Making Elected Offices Elected

New York’s provisions for filling vacancies in statewide office are diverse, complex, and riven with elements entrenched in law to achieve political advantage. Their combined effect is to devitalize the state constitution’s commitment to popular rule. Especially now, a time when democracy is under siege, it is crucial that all the paths to power in state government remain as democratic as possible, commensurate with efficient, effective governance.

A comprehensive, democratic approach to filling vacancies in top elective positions would have these elements:

1. Strengthen and reassert the constitutional principle that statewide elected offices must be filled by popular election as expeditiously as practicable.

2. For vacancies that occur early enough, before the start of the annual nominating process set out in the election calendar for the year, conduct an election to fill the office on the general election day. For vacancies that occur after the nominating process has started, hold the election on the general election day in the next following year. (Note: Avoid special elections for which there is added costs, turnout is lower, influence is exercised by the person charged with calling them, as they may result (New York City experience shows) in multiple elections for a single office in a brief span of time.)

3. Specify in the state constitution processes for immediately, automatically filling the vacated office on a temporary basis, with unelected persons serving in an acting capacity until an election is held. Whereas Lieutenant Governor acts as Governor; Executive Deputy Comptroller acts as Comptroller; Solicitor General acts as Attorney General. For U.S. Senator and Lieutenant Governor vacancies, interim acting appointments would be made by the Governor with advice and consent of both legislative houses required. For Comptroller and Attorney General, deputies specified in a succession statute should assume interim responsibility in the period preceding the required election. No non-elected person would hold unqualified status in these positions.

***

*They are among the three New York U.S. Senators, ten governors, eleven comptrollers and six attorneys general who first entered their offices in accord with vacancy filling positions. Comptrollers and Attorneys General were not chosen by popular election until 1846. U.S Senators were not chosen by popular election before 1913. James Mead is not included. No appointment was made prior to the special election to fill the Senate seat vacated by Royal Copeland at his death in July of 1938.

**This followed the earlier statutory change (1951) providing for holding required elections to fill vacancies in U.S. Senate seats only in even numbered years (see above). Republicans believed that statewide elections in odd numbered years favored Democrats, especially if there was a mayoral election in New York City scheduled that would boost turnout there.

***

Gerald Benjamin is Emeritus Founding Director of The Benjamin Center at SUNY New Paltz.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The New State Budget is a Start, But New York Still Needs to to Do More for AAPI Communities

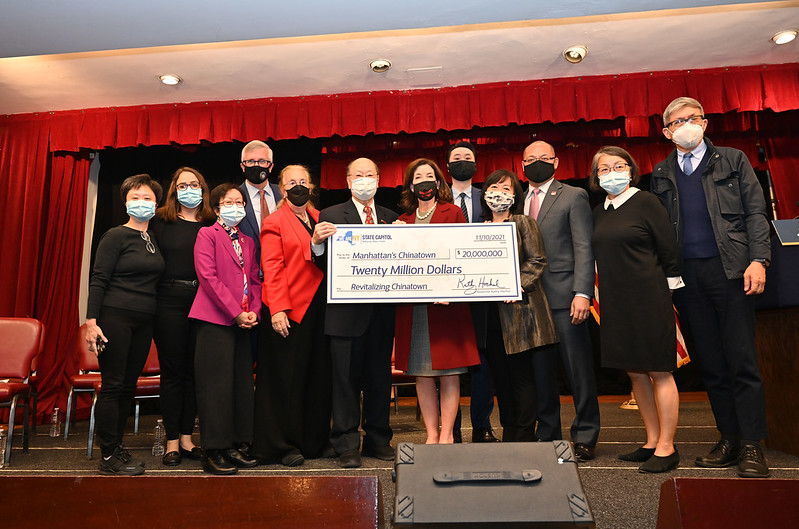

Gov. Hochul presents funding for Chinatown (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Office of the Governor)

I immigrated from Taiwan to the U.S. at age 27, with just two pieces of luggage, because of my belief in the American Dream.

Like most Asian-American immigrants, I understand the struggle of acclimating to a new country and a new city. You must navigate new systems and overcome language barriers. And now, as Asian hate crimes continue to soar, many in the Asian-American Pacific-Islander (AAPI) community find ourselves fearful within our own city and grappling with how to protect ourselves.

The recently-passed New York State fiscal year 2022-23 budget will include $20 million to support community organizational efforts to aid the AAPI community in New York, which is double what the state spent on AAPI funding last budget but only a third of the $64.5 million requested by the newly-formed AAPI Equity Coalition this year.

While this is a good start in providing Asian-American organizations with more funding, more needs to be done to solve the systemic issues that are at the root of the problems facing the AAPI community today. The state needs to prioritize combating the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, bridging the language gap for Asian immigrants, and providing support to the grassroots organizations already within New York’s AAPI communities.

As crime rates have gone down in New York City overall, hate crimes against Asian-Americans have increased by 400%. My heart breaks every time I see another story about violence against Asian-Americans, especially in a place like New York that boasts inclusivity and diversity.

Just last month, a man hit a 67-year-old woman in Yonkers 125 times just because she was Asian.

Now we have women and seniors lining up for access to free pepper spray, just to feel somewhat secure against what seems like daily senseless and hateful acts of violence. We cannot allow Asian people to continue to live in fear of being attacked or discriminated against any longer.

In order to prevent future hate crimes, we need to provide Asian communities with culturally-sensitive resources to apprehend and prosecute those committing these acts of violence, as well as develop a program for non-English speaking victims to safely report hate crimes and to receive counseling and support.

The Asian immigrant community, in particular, has very few resources because of language and cultural barriers. During my 10 years working as chief of staff for State Assemblymember Peter Abbate, many constituents came to me and our office when they had issues with the social services, education, and health care systems, often because they could not understand how things worked and there were little-to-no appropriate resources to help.

So many lives could be improved by expanding language access to government agencies and programs, providing interpreters at polling sites, and supporting nonprofit organizations working relentlessly to provide crucial services to immigrants.

Asian communities are historically underserved, underfunded, and underrepresented in New York, which is why I continue to call attention to their needs. Now more than ever we need to show AAPI New Yorkers that they are being heard, that they are being seen, and that they are being protected.

We need to bridge the gap between the AAPI community and state government — this is why I hope to be in Albany next budget season to fight for more funding for the AAPI community, and provide it with resources that are long overdue.

Asian-American immigrants should have the resources they need to not only survive but thrive as they pursue their American Dream, just as I have.

***

Iwen Chu is running to represent the newly-created State Senate District 27. She is President of Star and Stripes Democratic Club and was Chief of Staff for Assemblymember Peter Abbate for the past 10 years. On Twitter @Iwen4NY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Change I Didn’t Know NYCHA Needed

Repairs at NYCHA (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

More than three decades ago, my family was one of the first to move into Washington Heights Rehab, a New York City Housing Authority development. It’s in this development where I’ve since raised my three children and it’s the place that I’ve always called home. But like other NYCHA developments across the five boroughs, our building became the subject of disrepair, deferred maintenance, and difficult living conditions.

That’s until an initiative led by a mission-driven team of developers transformed our apartments into modern, beautifully-renovated homes. The initiative delivered the change my building most certainly needed, and I believe more broadly offers unexpected hope to the city’s 400,000 public housing residents.

About 15 years ago, the deteriorating conditions of Washington Heights Rehab started to come to a head. What was once a pleasant place to live began to crumble into a building that was an unhappy, unhealthy, and in some ways, unsuitable place to call home. For whatever reason – whether it was funding or an overworked housing authority – maintenance work came to a grinding halt. We began to witness water coming down walls, increased amounts of mold, more rodents, and frequent garbage problems. It got to a point where essentially everything in our building was damaged.

I realized then that our situation wasn’t necessarily unique but that didn’t make it any easier to handle. As a mother, I felt neglected and hopeless. The conditions made providing and caring for my family that much harder. As a tenant president, I felt disempowered. I knew I had to do something to help myself, but, as the voice of my community, I also knew I had an obligation to help my neighbors. However, no matter how much I tried, little improved because funding for NYCHA had gone dry.

Fortunately, change came – albeit in a way that wasn’t necessarily expected. During the summer of 2019, I learned about a team of non-profit and for-profit developers and social service-providers that would soon be leading the management, rehabilitation, and renovation of Washington Heights Rehab. As it turned out, the team known as the PACT Renaissance Collaborative (PRC) also was tasked to lead the same massive rehabilitation work at 15 other developments in Manhattan as well. We had initial meetings with their representatives where they explained the plan, and where we were also given the opportunity to be heard.

In 2019, we were skeptical; we had been promised change before when in fact nothing did change, and the idea of a private developer coming in to be that change certainly raised some eyebrows, too. But nearly three years later, we’re ecstatic because what’s occurred since those initial meetings has been transformational. PRC has fully renovated each and every apartment in our development with new kitchens, bathrooms, living rooms, flooring, windows, and doors; brought new life to commons rooms and shared spaces; and they have ensured that when a repair or maintenance is needed it’s taken care of.

This work and their effort have rejuvenated Washington Heights Rehab and we’re truly grateful for everything that’s been accomplished. After more than a decade of uncertainty, we feel like we’re now shown the respect that every tenant – especially public housing tenants – should be given by their landlord and property managers.

I understand that PACT Renaissance Collaborative is not the only team tasked with bringing new life to public housing across the five boroughs, so I cannot speak to the quality of work being completed as part of NYCHA’s larger PACT program. What I do know, though, is that when the right team is chosen to lead the rehabilitation and management of NYCHA buildings through PACT – and when residents are heard in the planning processes of the program – that incredible change can occur. My building and the quality of my living conditions are a testament to just that.

To all my fellow public housing residents: we’ve been through a lot over the years. But, I now have hope that we are turning a corner on this crisis of disrepair thanks to mission-driven teams like the PACT Renaissance Collaborative. From the bottom of my heart, I encourage NYCHA residents to open their hearts and minds to the opportunity that change might present through this PACT program.

Ask your questions, make sure to be heard, and demand accountability from those leading the PACT process. But know that the program does hold the potential to transform your apartment, building, and life for the better.

***

Margarita Duran is a 35-year NYCHA resident and TA President of Washington Heights Rehab.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.