NYS Public Service Commission: Do the Right Thing for Frontline Communities

New York City from above (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

It doesn't often happen that New York State has an opportunity to take decisive and meaningful action to address deep-rooted issues that have plagued the Bronx, New York City, and our state for way too long — environmental injustice and climate change.

This month, the seven members of the New York State Public Service Commission hold our fate in their hands as they vote on the Champlain Hudson Power Express (CHPE), a permitted and shovel-ready renewable energy project contracted with the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA). CHPE is poised to create sorely needed jobs this year, deliver clean electricity year-round to New York City by 2025, and begin to finally break our unhealthy dependence on fossil fuels. It's a classic upstate-downstate dynamic, with most commissioners living in northern New York making a decision that will directly impact us here in the city.

The Bronx is ground-zero for the asthma epidemic in New York City, with hospitalization rates 70% higher than the rest of the city and 700% higher than the rest of the state. The areas of the South Bronx and Northern Manhattan have one of the highest death and disease rates from asthma in the country. And this enraging reality is a result of the historical injustice in our politics, planning, and perverted economic development on the backs of frontline communities of color. The Bronx was chosen by design to bear the brunt of the state's addiction to fossil fuels, from transportation infrastructure to power generation. We can no longer tolerate this construct.

90% of New York City's power comes from burning toxic fossil fuels. In this twisted reality, our underserved communities are literally paying to be polluted, just as fossil fuel generators fleece our wallets without consequence. This winter we were slapped with historic spikes in our electricity bills because we are forced to depend on volatile natural gas prices. Enough is enough. The New York State Public Service Commissioners should approve the Champlain Hudson Power Express contract that will provide clean power to over 1 million homes, slash air pollutants by 20%, displace fossil fuel generation by 25%, meet 20% of the city's power needs, contribute 7% to reach our state's 2030 clean energy mandate, and help lower wholesale energy prices. It's a no-brainer.

CHPE is committed to union labor and working with local communities to ensure there is diversity, equity, and inclusion at the center of this project. I have witnessed this firsthand by participating in the foundation of CHPE's working group on the subject made up of local environmental justice, workforce development, and community leaders. In addition to this concrete commitment to diversity, the project is launching a $40 million green jobs training fund available for residents of underserved communities, including the Bronx, to gain the skill-sets necessary to pursue a career in the green economy.

Inaction is not an option we can live with any longer. If we forgo CHPE, the next comparable project is guaranteed to be more expensive and come into service later. I call on the Public Service Commission to do the right thing and approve CHPE.

***

Assemblymember Kenny Burgos represents parts of the Bronx. On Twitter @KennyBurgosNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Divorce Got Easier During Covid; That Shouldn’t Change

Brooklyn municipal building (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

A few months ago, in my role as a family attorney, I settled a fairly ugly child custody dispute in Queens Family Court. As my client and I debriefed, he asked me, “I probably saved some money with this being entirely online, huh?” I didn’t have to think twice. “Absolutely,” I told him. “At least a thousand dollars.”

I was underestimating. After I did the math, I estimated that my client saved around $3,750 solely because the case was litigated virtually, as nearly all family law cases have been for the last two years, owing to New York’s covid-necessitated court shutdown. And this was a relatively simple case, where the only issue was custody of kids – if it had been a complex divorce with financial issues to be determined in addition to custodial ones, he would have saved many thousands more.

In normal times, attending court involves sitting around from 9:30 a.m. for a morning case, or 2 p.m. for an afternoon one, until the court officer tells you it’s time. Sometimes you get in right away – others, you wait hours. Sometimes you get kicked past lunch hour, which goes till 2:15 p.m. Sometimes you see the judge, they give you a few morsels of judicial wisdom, and they tell you to go in the hallway and work it out and come back later. Waiting is baked into the process.

Virtual court, with appearances held remotely, has rewritten this process. For the last two years, lawyers have gotten specific appearance times, every time. If the court tells you to log in at 11 a.m., you will almost certainly be heard by 11:05. The longest I’ve waited for a virtual appearance to begin was 20 minutes. And if we get kicked out and told to negotiate and come back later, we can do it on the phone, hang up when we’re done, and work on other cases. For lawyers used to thumb-twiddling for hours, this certainty is a welcome scheduling gamechanger. And it’s even better for clients, because it saves them serious money.

Like nearly all attorneys, I charge for in-person waiting time, because time spent in a courthouse is time I can’t spend in my office working for my other clients. My hourly rate for my custody client’s case was $375, which is on the low end of New York City family lawyers. We can safely estimate an average of 120 minutes of wait time per appearance if we had been in-person. Do the math, and he saved $3,750, just because we didn’t have to show up in person. For most parents and spouses, this is not chump change – it's a rent or mortgage payment, maybe two, it’s a family vacation, it’s savings.

Family litigation is already prohibitively expensive for most families. Unlike corporations, which have legal funds, or personal injury litigants, whose lawyers work on contingency, spouses and parents have direct exposure to legal fees. New York has the second-highest solo or small firm lawyer rates in the country, averaging out to $357 an hour. (Big family law firms here charge more – I know divorce lawyers who top $1,000 an hour.) And make no mistake – litigating a divorce or custody case to resolution takes many hours. There’s a reason most family attorneys can tell you about the client who took out a usurious “divorce loan” they’ll be paying back for a lifetime. By making family disputes cheaper, virtual court reduces the chances that a parent or spouse will bankrupt themselves to fund it.

There are other benefits to remote court for family law matters. For disabled clients, even making it to the courthouse can be a difficult journey, or even an impossibility. Litigants must take at least a half-day off work, something only the privileged can afford, and pay a babysitter. Allowing parents and spouses to log in on their phone or laptop from home or the job eliminates all these obstacles to access. Being remote has also allowed me to take on more pro bono work – I can represent one needy client in a courthouse far from my home, only because court has been on my computer. If her case moves back to in-person, I am honestly not sure what I’ll do.

And that day is coming. Across the state, courts are moving back to in-person appearances, including some courts in New York City. Put aside, for a moment, the covid risks, although that alone is enough reason to consider this foolhardy. Consider why exactly we are demanding divorcing spouses and parents in custody battles take off work to sit in a courthouse for hours and watch their savings drain away.

Seasoned divorce litigators will tell you that virtual court is strange, different, that they need to look a witness in the eyes when they cross them. And that’s true. I conducted one trial virtually during the pandemic, and I didn’t love it. Critically, though, formal trials, with testimony and cross-examination, are a rare part of family litigation – the vast majority of cases settle first. But even those cases that settle can require five, ten, thirty court appearances, all before anyone is sworn in as a witness and trial begins. There is simply no reason to have these appearances in person.

Too many parents and spouses find themselves caught up in the brutal maelstrom of litigation before they even realize it’s happening. Costs build up quickly — quicker than most litigants predict. I don’t say this lightly, I have seen lives destroyed by this process. I have seen parents on monthly payment plans to lawyers that equal the amount they are receiving in child support. I have seen pensions sold and 401Ks cashed out to pay for trials. For anyone but the very rich, litigating a divorce or custody case can be the perfect financial storm.

Remote court is not even close to a cure-all. But it is a serious policy change that has real, positive effects, and that in some small way makes the nightmare of family law litigation more bearable. New York would be wrong to go back to “normal,” when normal has caused so much unnecessary harm. Fine, hold trials in person. But other than that, divorce and custody cases should be conducted virtually, even after this pandemic is finally behind us. Access to justice demands it.

***

John Teufel is an attorney. On Twitter @JohnTeufelNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

An Early Test of The Adams Administration’s Values and Tech Prowess

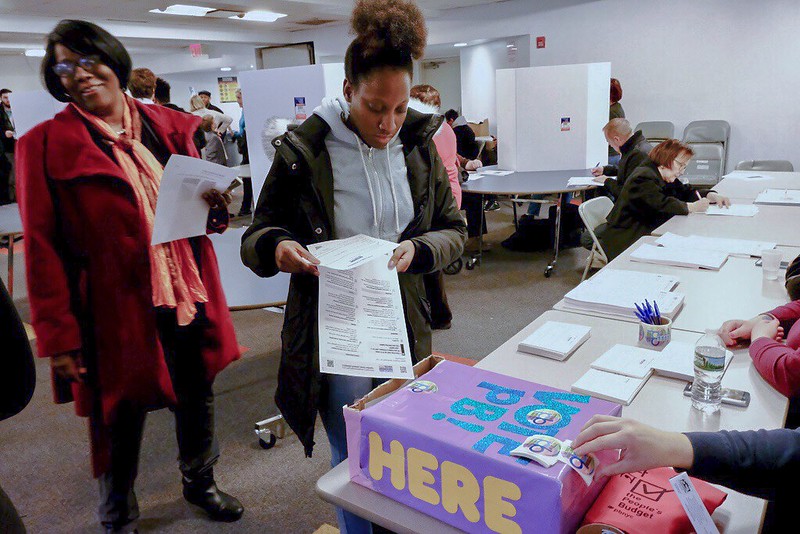

Participatory government in-person (photo: New York City Council)

In 2019, New Yorkers voted overwhelmingly in favor of establishing a Civic Engagement Commission that would modernize how the city and its residents worked together to identify and solve problems at the most local levels. That commission hasn’t been earning itself many headlines, but the participation platform it set up at participate.nyc.gov could support world-class civic engagement programs. Whether or not the administration of Mayor Eric Adams uses it to do that will be an early test of its basic competency and technology prowess.

Participate.nyc.gov is much more than a basic government website. It’s a deployment of an open source participatory democracy platform called Decidim. First founded in Barcelona in 2016, Decidim is free and open source software used by dozens of municipal governments around the world including Helsinki, Mexico City, Zurich, and Milan. The software is a successor of Consul, a similar platform that facilitated genuinely innovative and wildly successful crowd-sourced city planning, participatory budgeting, and decision-making in Madrid, Spain.

The idea behind Decidim and Consul is simple: give the public a single, unified, open source platform and standard set of tools for participating in local civic engagement programs. These platforms allow city residents to be organized into different types of districts to have discussions, make proposals, vote on projects, take surveys, and generate the type of feedback that city agencies and elected officials can and should use to understand how best to improve our neighborhoods, city, and government operations.

Since New York City’s deployment of Decidim is just beginning to be used in a few City Council districts participatory budgeting processes, it’s difficult to see the platform’s potential. To do that, it’s best to visit decidim.barcelona (turn on Google Translate if you don’t read Spanish) and see how they’re using the software. On that site you’ll see two main menu items, which translate to Participatory Processes and Participation Bodies, which is more easily understood as Processes and Spaces.

Processes are civic engagement programs, such as a participatory budgeting cycle, a city planning project review, or a charter revision.

Spaces are groups of people, often divided by their district, operating under a defined set of rules about membership and governance.

By applying processes to spaces, the Decidim system deployed at participate.gov.nyc could host many of the city’s existing civic engagement processes immediately, right “out of the box,” with no need for any expensive custom development.

Here are some examples:

-City Council members and districts could use it for participatory budgeting;

-Community boards could publish news, events, meeting minutes, files, videos, surveys and more – replacing their websites;

-City commissions could replace their websites with Decidim as well, and use its collaborative editing and commenting features to enable residents to attach their ideas and comments to specific language in a document.

Beyond these basics, the system could be used for so much more: to

-host discussions about pending legislation;

-gather feedback about land use issues;

-provide a unified calendar of city agency outreach events;

-facilitate petitioning the city council to introduce legislation.

The list could go on.

All of these new tools and features can frighten politicians and civil servants because they’re experts in the current systems for public engagement and any change could alter the power dynamics to which they’ve become accustomed and dominate. As such, there is natural resistance to utilization of different, better platforms and processes. Fortunately, Mayor Adams claims to be tech literate, eager to reform city government, and focused on public participation.

During the mayoral election, Adams pledged to establish MyCity, “a single portal for all City services and benefits.” One of the key “services and benefits” the city offers its residents is civic engagement. As such, a unified platform that many different agencies use for civic engagement purposes fits nicely with Adams' vision.

And, as an open source platform built with the popular framework Ruby on Rails, Decidim is a platform that the city can own and run itself, without needing to pay expensive IT consultants or exorbitant licensing fees. Indeed, it's the perfect project for the Digital Service Organization (DSO) the city should have already launched.

Indeed, the participate.nyc.gov system could become an integral component to the MyCity dream. Decidim’s login system uses open standards that could and should be integrated with the inevitable user authentication system that is a prerequisite for MyCity. And its data, formatted into configurable open data feeds, can and should flow elegantly into other city information management systems, such as City Record event feeds or City Planning project pages.

To see the true value of Decidim, the Adams administration must develop an understanding of the open source concept that makes it possible. It’s hard for many people to understand how sophisticated software like Decidim could be available on the internet to download for free, with no limitations on how or by whom it's used. It seems too good to be true, but it is.

Open source technologies like Linux, WordPress, and Bitcoin get a lot of the headlines, but there are actually hundreds of thousands of open source applications out in the world, and that number is expanding all the time. Most of those applications are components that must be combined with other ones to make a system, but some are full-fledged applications like Decidim.

As I’ve mentioned in other articles, open source is transforming how the government delivers services all over the world, but New York City’s IT bureaucracy and poor leadership have not adopted proven techniques to benefit from these advancements because powerful special interests make tremendous amounts of money by keeping the city in the technological dark ages.

Companies that run core city software systems like Microsoft, Dell, Tyler, ESRI, Accenture, and others want to keep the city addicted to their proprietary software systems. To achieve that goal, these companies have fused themselves with city agencies like the Department of Information Telecommunications and Technology (DoITT), which are much more comfortable signing expensive software contracts with these companies than they are deploying and managing open source software systems themselves. Meanwhile, city technology executives routinely work at vendors before and after their time in government. The revolving door spins very quickly.

If Mayor Adams develops an understanding of how to effectively use open source software to make the city more efficient, effective, and equal, then there is no limit to the amount he could achieve. He has a great opportunity to start off on the right foot by organizing a DSO unit to manage the open source Decidim software at participate.nyc.gov and aggressively utilize that software to deliver New Yorkers the world-class civic engagement experiences we deserve.

Delivering compelling civic engagement programming through participate.nyc.gov is a great way for Adams to prove he has the technological prowess and genuine desire for reform that he claimed to have during the campaign.

It’s time to deliver.

***

Devin Balkind is a nonprofit executive, civic technologist, and startup advisor running for Public Advocate as the Libertarian Party nominee. On Twitter @DevinBalkind.