New York Must Fix the BQE; Governor Hochul Can Help Get Things Started

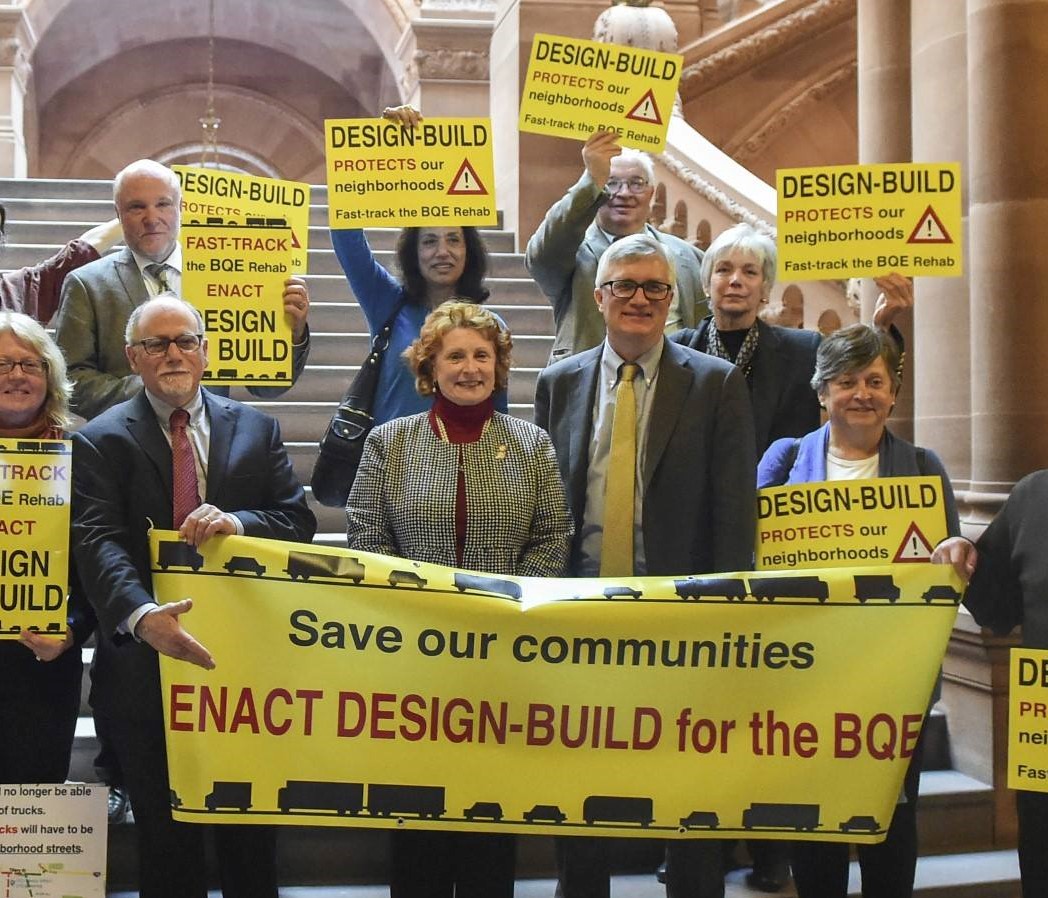

The authors at a press conference related to the BQE

For years, residents, motorists, and headlines have screamed about the crumbling triple-cantilever on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Repair plans have been delayed, presented, and rejected. We are not moving forward fast enough to repair the triple-cantilever or to envision and build a coherent 21st Century solution for the entire BQE corridor.

We can fix the BQE—and we must—but we can’t do it overnight. We need a solution that’s future-focused and environmentally-sustainable along the entire I-278 corridor in Brooklyn. The BQE connects over a dozen neighborhoods throughout western Brooklyn, and it’s a key link in the Interstate highway system serving the entire tri-state metropolitan area and beyond. It will take a multi-pronged effort by many people and agencies at the city, state, and federal levels.

Let’s start with a good first step. Governor Kathy Hochul can get the ball rolling by signing our “Weigh In Motion” (WIM) bill A2316/S2740. The WIM bill would reduce the number of overweight trucks on the BQE by allowing New York City to issue violations electronically to trucks exceeding the legal weight limits. Overweight trucks are a significant factor in the deterioration of the triple-cantilevered portion of the BQE around Brooklyn Heights. Removing them from the BQE will extend its lifetime and allow us time to plan for a fix. This bill is red-alert critical and is currently on the governor’s desk.

To keep illegally heavy trucks off the crumbling triple-cantilever requires the installation of electronic sensors throughout the corridor to capture the offenders before they actually enter onto the triple-cantilever. Law enforcement simply cannot stop and remove enough trucks from the roadway to adequately discourage overweight trucks. More law enforcement agents won’t do the trick. In this very dense street environment, there just isn’t enough physical space to do it. And installing the sensors throughout the corridor will mean that trucks can’t avoid enforcement by exiting to local streets and then quickly reentering just beyond the sensors, ensuring that this approach is unlikely to divert overweight trucks to other routes through our neighborhoods.

Overloaded trucks also cause increased carbon emissions, harming the public’s health and advancing climate change. We all need to care about this.

In August, the city released a plan to extend the life of the BQE cantilever for another 20 years to allow for the time necessary to envision a long-term solution for the entire BQE corridor that reduces reliance on polluting long-haul freight trucks and transitions more freight to waterways and rail. Their plan includes getting overweight trucks off the BQE. This will allow us time to examine solutions (including tunnel alternatives) and prioritize climate for a just and sustainable transition from fossil fuels.

In this era of rapidly advancing climate change, we need smart and environmentally-just surface transportation infrastructure. For too long, the state has not been an active partner in this pressing project and it’s time for that to change. Governor Hochul’s signature on this critical legislation cannot come soon enough.

***

New York State Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon represents District 52 in Brooklyn and New York State Senator Brian Kavanagh represents District 26 spanning parts of Brooklyn and Manhattan. On Twitter @JoAnneSimonBK52 & @BrianKavanaghNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Members of a Community: Opposition to Local Shelters Leaves Vulnerable Families Even Worse Off

Finding homes for everyone (photo: Emil Cohen/City Council)

On October 29, the New York City Department of Social Services sent a letter to Brooklyn Community Board 11 providing notification of a planned homeless shelter to be built in Bensonhurst. The facility would be for 75 families with children, with priority given to those “who have roots in this community and this area of Brooklyn more broadly.”

Brooklyn CB11 and neighboring CB10 encompass Bensonhurst, Bath Beach, Dyker Heights, and Bay Ridge. These community districts are the only two in the borough without a single shelter bed, despite averaging nearly 300 individuals in the shelter system at any given time whose last permanent address was in these districts.

The city’s current plan to create community-based shelters in all 59 community districts is logical, compassionate, and promises the most potential for helping people return to stable housing. For decades, most shelters have been clustered in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas where it was cheapest to build and operate them. Not only has this allowed some neighborhoods to avoid doing their fair share to address a problem that exists in their own communities, but it has serious negative consequences for those experiencing homelessness, especially families.

Federal statute guarantees students living in a homeless shelter the right to remain in the school they were attending before they became homeless, which is invaluable to children whose living situation is unstable. Students living in homeless shelters missed nearly one in every four days of school on average last winter and spring and had an attendance rate about 10% lower than students with permanent housing. Families experiencing homelessness in communities with no shelters often must choose between entering a shelter that is inordinately far from their school or remaining homeless so they can be close to their school.

Assemblymember William Colton, whose district office is across the street from the site of the planned family shelter in Bensonhurst, posted a press release on his Assembly webpage on November 1, saying that he “alerts the community that the city is planning to build another homeless shelter at 137 Kings Highway in Brooklyn.” During the November 9 CB11 monthly meeting, Colton announced the planned shelter, stating, “It also has some problems in terms of, again, the location. It is in a very residential area.” Along with the fact that shelters are, quite obviously, “residential,” families with children who are lacking permanent housing in his district are human beings who deserve shelter in their communities, not to be warehoused in non-residential areas.

Ten months earlier, during Brooklyn CB11’s January meeting, while addressing a different proposal for a single men’s shelter in another part of the district, Chair William Guarinello referenced Bensonhurst’s 1,200 families that are in temporary housing and said that the community board felt that facility “should have more been a family shelter if you were going to try to serve our homeless in our community.”

Schools in Brooklyn CB11 and CB10 are in school districts 21 and 20. For the 2019-2020 school year — the last before the pandemic — 6% of all district 21 students and 5.5% of all district 20 students, totaling 5,172 students who experienced homelessness within the past year. The Department of Education’s economic need index takes into account students’ financial hardship, including if they've lived in temporary housing the past four years. Data shows 73.1% of district 21 students meet this criteria and 74.6% of district 20 students, up about 12% since 2017.

On November 15, at the Community Education Council District 21 (CEC21) monthly meeting, a resolution to oppose the planned homeless shelter for families with children in Bensonhurst was put forth. As a member of the council, I was able to offer thoughts after it was introduced. I focused on the fact that we have families and students experiencing homelessness in our district, but we do not currently have the ability to help them here, in our community. I stated the statistics as they relate to our district and how the lack of shelter beds in our part of Brooklyn presents our most vulnerable families with additional obstacles to getting back on their feet. Our council voted against considering the resolution that evening.

On November 21, News12 filed a report from the site of the planned Bensonhurst shelter, stating that they “were supposed to meet one-on-one with Assemblyman William Colton,” but 50 people happened to show up to voice their frustration. Colton had directly messaged and emailed people earlier that day, advising that he had “been contacted by Channel 12 News to interview [him] and residents about this proposal” and welcoming people to come. Colton told the reporter that he “found out about the building of the shelter a week ago,” when he had learned of it three weeks earlier.

These are minor discrepancies, but presenting this false narrative inflames the conversation. The CEC21 resolution opposing the shelter stated that constituents “vehemently object to the building of the homeless shelter,” at a time when there had been no reporting on it and news of the shelter was only known to the small number of people who had attended the CB11 meeting six days earlier. It also stated that “community leaders have publicly denounced this project,” when Colton was (and still is) the only local leader to have publicly spoken out in opposition.

It is fair and reasonable for any shelter to be evaluated and given proper consideration, but the neighborhoods of CB11 and CB10 have need for shelters and opposing every proposed facility outright is unproductive. Devoting one’s efforts to denying families with children a place to get back on their feet in their own community is shameful.

The week after Thanksgiving, a community outreach non-profit I serve as a board member and volunteer for was contacted by another organization to see if we could assist families who were left homeless by a fire in their apartment building. One family – a single parent with several children – was given the opportunity to enter a shelter. The facility was in East New York, over an hour away by public transportation from their children’s District 20 schools. They chose to stay in their community, close to their schools, without stable living accommodations, 10 minutes from the site of the planned Bensonhurst family shelter.

***

Jay Brown is an engineer who serves as a member of Brooklyn Community Board 11 and the New York City Department of Education District 21 Community Education Council. On Twitter @JayBrownNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How Health Care, Tech, and the New Federal Infrastructure Law Must Connect

Getting health help through infrastructure (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

President Biden and Congress took a significant step in shoring up access to health care by enacting the infrastructure bill.

The COVID-19 crisis shined a spotlight on broadband inequity and its impact on access to health-care services. While our country leapt forward on digital health, some of the neighborhoods and families who need it most were left out.

In July 2020, EmblemHealth surveyed New Yorkers and found nearly one-third of Black-led and almost one-quarter of low-income households had inadequate access to the internet, compared to just 18% of the general population. Low-income and Black households were also less likely to have more than one digital device at home, further limiting their ability to use telehealth.

Policy discussions celebrate the milestone that serious health conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and high-blood pressure, can now be monitored from home by using apps that connect directly to your doctor. But that often requires individuals to have good internet connections and robust data plans. Many families rotate through phones, have limited data plans, or have no phones altogether. The digital divide is a deficit, and reducing health care disparities requires expanding broadband access.

The new infrastructure law will help close these gaps. It commits $65 billion in federal funding to increase broadband access in underserved areas, including a $30 per month voucher for low-income families to use toward an internet service plan of their choice. This assistance will unlock access to digital health, telehealth, and at-home health monitoring.

These changes will make a difference for American families, including many in New York City. It’s also a wakeup call to the policy community, which has embraced the promise and potential of digital health, not to lose sight of people without access or with limited access. Passage and enactment of this legislation will have tangible results. Now the challenge is for all of us working in the system to unlock this potential for the people we serve.

***

Karen Ignagni serves as President and CEO of the EmblemHealth family of companies.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.