De Blasio Leaves Adams a City Budget Mess

Mayor de Blasio at a budget briefing (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography)

Some of us in government are old enough to remember when Mayor Bill de Blasio took office almost eight years ago, fulminating to any reporter in earshot about how his predecessor, Michael Bloomberg, left him with expired labor contracts that presented the city with an “unprecedented” fiscal challenge.

“The future should not have been mortgaged in this way. But it was by the previous administration and we will have to grapple with it,” he told The Observer at the time.

Talk about the pot calling the kettle black.

When he takes office less than a month from now, incoming Mayor Eric Adams will have to deal with the financial mess de Blasio is leaving behind. Only, it’s a lot bigger.

After years of treating the city’s budget the way rock bands treat hotel rooms, Mayor de Blasio will be handing his successor a city in far worse financial shape than the one he took the helm of in 2014. Like de Blasio before him, Adams will also have to negotiate expired municipal labor contracts in short order – but this time, with a depleted labor reserve, a projected total of $8 billion in deficits in the next three fiscal years, and nearly $4 billion in annual debt service. And he will have to grapple with all this amid a global pandemic that is fueling hysteria and uncertainty, skyrocketing inflation, and a dragging economic recession.

Even under the best circumstances, it would be extremely difficult for the Adams administration to correct eight years of mayoral monetary malfeasance, in which an already bloated budget grew by 36%, or three times the rate of inflation. Nor will he be able to lessen the city’s long-term pension obligations, which are much larger now due a workforce that has grown by more than 35,000 during the de Blasio administration.

But there is one thing Mayor Adams can do almost immediately to put this city on a more sound fiscal footing: shore up the city’s cash reserves.

This is not a new idea, of course, but it was not entirely possible under the terms of the New York State Financial Emergency Act (FEA), passed in late 1975 after New York City came just hours from bankruptcy. The FEA imposed strict accounting rules on the city, including requiring an annually balanced budget. So for decades, whenever the city has had a budget surplus, the best we could do was stash some money in the Retiree Health Benefits Fund and roll over the rest to “pre-pay” future debt. But none of this could be used to plug current budget gaps.

This restriction was finally removed by state law in 2020, which earlier this year led to the creation of the Revenue Stabilization Fund, a real unrestricted rainy day fund. The Revenue Stabilization Fund would have been the perfect place to park at least some of the $22 billion the city received in federal aid this year, particularly about $6 billion that had no strings attached, to help pay for future budget gaps and as a down payment for labor contracts. Instead, the mayor squandered this once-in-a-generation cash infusion on costly recurring programs, like mental health services and rental vouchers.

The city’s rainy day fund now sits at $1 billion, or less than 1% of the $100 billion-plus operating budget. The nation’s second largest city, Los Angeles, has an unrestricted cash reserve of 17%. Dallas has a reserve of 25%. Phoenix and San Antonio have cash reserves of more than 28% each.

Our city’s cash reserves are not only woefully inadequate to meet future fiscal challenges, but they also cost us significantly more in annual debt payments. To achieve the highest level of creditworthiness — AAA — rating agencies require municipalities to have a minimum 15% budget reserve. New York City has AA, AA2, and AA- ratings from, respectively, Standard & Poor's, Moody's, and Fitch — the big three rating agencies. That is several tiers lower than AAA. Just like a personal credit score, a lower municipal credit rating means the city has to pay higher interest rates on loans, and when you borrow tens of billions of dollars for capital projects, like New York City does, just one percentage point translates into tens of millions more in payments.

There is no good reason New York, a city with the financial might of a small country, should not be able to set aside at least 20% of its budget in savings. There is no good reason we should pay higher interest on our debt than San Jose or Dallas, cities with one-tenth our GDP. There is simply no good reason we should face a budget shortfall when we spend more than 47 states and 170 countries.

Of the many bad decisions this mayor has made, mortgaging our future for his political projects was one of the most damaging. Let us hope Mayor Adams does not follow in the footsteps of his profligate predecessor and that he not only believes this city is worth saving, but worth having more savings.

***

City Council Member Joseph Borelli represents parts of Staten Island and is the Council’s Minority Leader. On Twitter @JoeBorelliNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Taking Mental Health Care in New York City to the Next Level

Mental health first responders via B-HEARD

Last week, the New York City Council voted to amend the City Charter to establish the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health as a permanent part of our city government. The vote comes at a critical time – as New Yorkers continue to feel the long-lasting mental health consequences of the pandemic.

The vote is also the culmination of years of work. In the wake of decades of state and federal neglect that left too many people without the mental healthcare they need, New York City became the first major American city to support mental health services through local tax levy funds. As a result, today New York City is delivering more mental health services, in more places and in more ways than ever before. These services are essential and effective.

Built on the strong foundation of ThriveNYC, our office coordinates a much-needed, all-government approach to mental health, and works with 13 city government agencies and over 200 community-based organizations to close gaps in mental health care through innovation. Our programs are not intended to replace the behavioral health-care system, but to enhance and supplement it with a laser focus on reaching people who would otherwise go without care.

The results are clear. Older adults with depression and anxiety are getting better thanks to clinicians we brought to senior centers. Victims of crime feel safer because of advocates we placed in every police precinct. New Yorkers with serious mental illness are staying engaged in care and securing permanent housing through mobile treatment teams the city created to fill in where state funding fell short. Since 2016, New Yorkers have reached out to our mental health helpline – 1-888-NYC-WELL – more than 1.5 million times for help, with calls soaring during the pandemic. Ninety-three percent were satisfied their needs were met.

In the face of a nationwide social worker shortage, we have demonstrated new ways to deliver needed mental health support without trained clinicians. Right now, the new Academy for Community Behavioral Health, run by CUNY School of Professional Studies in partnership with our office and the Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity, is offering free courses and certification programs for social service providers and city government employees. The training will help them provide basic mental health support to the people they serve.

In Harlem, we are pioneering the city’s first health-centered, non-police response to 911 mental health emergencies. Early results show more people accepting help, fewer hospitalizations, and more community-based care. This is the next frontier of mental health emergency response reform, but it’s not the full story.

We also worked with the city Health Department to expand health-only mobile crisis teams that can be deployed through NYC Well, not 911. Now, from 8am to 8pm every day, these teams can arrive within two hours to help people in an urgent crisis – up from 2014 average wait times of longer than a day.

Recently we launched a new approach to prevent the next emergency, working with FDNY Emergency Medical Services and the Health Department to reach out to the 300 or so people who call 911 for mental health issues more than three times each month. With a proactive connection to needed services, we hope to prevent the next moment of crisis, and reduce the use of emergency resources.

We are also expanding mobile treatment teams and member-run Clubhouses across the city – with the goal of better serving more people with serious mental illness. As of this month, we are bringing new mental health services to every domestic violence shelter in the city, creating new treatment hubs for youth and young adults – especially those who have run away or experienced homelessness, and adding more clinicians to senior centers in communities of color.

There is so much more to do, especially as New York City continues to recover from the pandemic – which created significant mental health challenges and exacerbated long-standing inequities. It is time for the citywide conversation on mental health to focus on the future – we must be talking about how to bring more mental health support to people who need it most. An equity lens must guide every strategy going forward: we have greatly expanded connections to mental health care, but still not everyone has access to the care they need.

The next mayoral administration faces major challenges. Promoting mental health for all New Yorkers must be one of the highest priorities. Thanks to the leadership of Mayor de Blasio, First Lady Chirlane McCray, and the New York City Council – leaders in the future will also have more tools to tackle these challenges than ever before, including and especially the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health.

***

Susan Herman is Director of Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health. On Twitter @MentalHealthNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Key Considerations as the MTA Restarts Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign

Boarding the bus in Brooklyn (photo: MTA/Patrick Cashin)

The MTA announced this past summer that the borough network redesign studies that were halted by covid will resume this fall. A Brooklyn bus network redesign is long overdue, but it must be performed in the correct manner. We have no indication that such is the case.

The intent is to design routes “from a blank slate,” which is unrealistic. Existing route segments should be realigned and service gaps filled. Is the study’s purpose to reduce operating costs resulting from the 40% bus passenger decline since covid or to make destinations more accessible and shorten passenger trip times?

The study is not objective. The MTA begins with the assumption that the major problem is buses are too slow and one solution is to eliminate bus stops so that all local bus routes in effect become Limiteds. They propose providing more bus lanes or busways, without considering the impacts on traffic. Slow buses are not the problem. The problem is people's trips need to be faster with better and more reliable service and requiring fewer connections.

The MTA never solicited problems and possible solutions from Community Boards. Instead, they held lightly-attended and ill-publicized workshops merely informing the public what they are trying to accomplish. Opinions from the public were solicited on post-it notes. Does the MTA even care what you think?

Surveys were performed and quotes for the Brooklyn Existing Conditions Report were carefully selected that fit into the scenario of how the MTA wants to proceed. People also were stopped on the street where they were informed of the MTA’s goals for the study like having the buses go faster. The public was led to responses that would support the measures being proposed like more bus lanes and fewer bus stops.

This report sets the stage for wider spacing between bus routes, increased walking to bus stops and bus routes, fewer express bus routes (because they cost too much to operate) and straighter routes requiring additional transfers, although many (45%) riders surveyed preferred using only one bus even if it took longer.

These measures, the MTA believes, will encourage bus travel. They are wrong. Bus travel will be discouraged and patronage will further erode if more stops are removed and there is less route coverage. The MTA asks riders to choose between bus frequency and route coverage, implying they cannot afford to provide both. The question is absurd. An adequate system needs both frequency and coverage. It's like asking a prisoner who has not eaten in three days if he wants food or water.

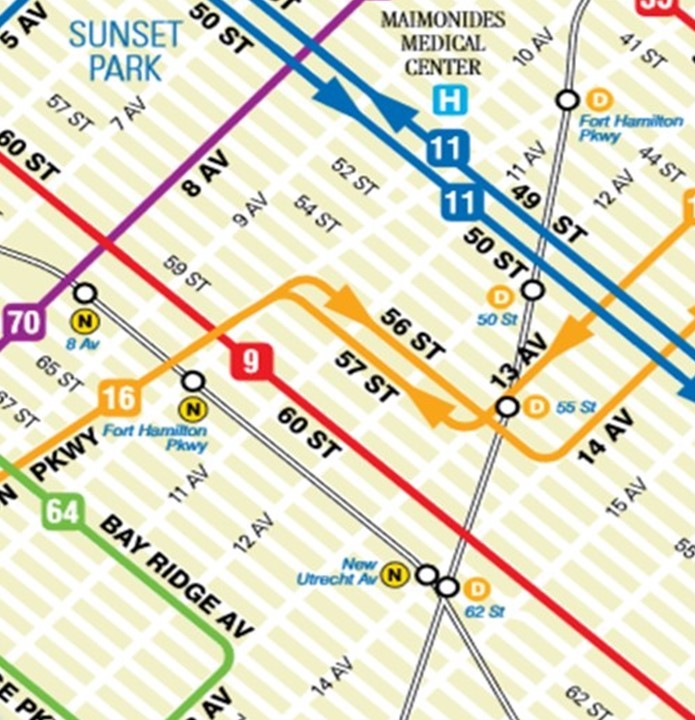

The MTA correctly states some bus routes are still based on 1920 trolley routes. And some bus routes are still based on 1930s bus routes. For example, the southern portion of the B43 is based on the need to directly serve Ebbets Field from Williamsburg, when today it would make more sense to better serve Kings County Hospital. The B16 doesn’t run straight on 13th Avenue because when the bus route started in the early 1930s, there was no 13th Avenue Bridge crossing the Sea Beach tracks. The bus had to be diverted to Ft. Hamilton Parkway.

|

The B16 doesn't serve Maimonides Medical Center |

Also, at that time Maimonides Medical Center was a small local Hospital called Israel Zion Hospital and did not merit a bus route along the length of Ft. Hamilton Parkway. So today the B16 serves double duty serving both 13th Avenue and Ft. Hamilton Parkway, when two separate routes would make more sense providing more direct travel.

The major purpose of the Brooklyn redesign study should be to alter outdated routes such as these so they provide more direct travel, reducing the need to transfer and therefore reducing travel time. That would encourage ridership.

Downtown Brooklyn has and will see more development than any other part of Brooklyn. Yet, the Existing Conditions Report states that due to the numerous subway lines operating there, its bus service needs to be trimmed and resources allocated elsewhere. That would result in additional bus transfers and travel times, rather than the opposite. There isn’t even any mention if there is capacity on the subways to absorb additional bus riders. If the subway was a better alternative, those bus riders would be using the subway today.

If the MTA follows through on its recommendations for the Bronx and Queens, Brooklyn will also likely see over half its local bus stops eliminated, resulting in longer walks to and from a bus route. This will result in longer trip times for passengers with minuscule savings in bus running times. That is because if a bus stop is lightly used, the stop is often skipped anyway. If it’s heavily used but eliminated, then the boarding times at adjacent stops will be increased and the only time saved are the seconds for acceleration and deceleration.

Extra walking is also very inconvenient during inclement weather and especially for those with mobility challenges. Massive bus stop elimination would discourage ridership. Why take a bus at all if your trip will still require you to walk a mile? You are better off taking an Uber or just walking the entire way. Over 2,000 people have signed the petition opposing massive bus stop elimination.

The study also needs to determine how to eliminate double fares, especially for short trips requiring multiple vehicles. Why should a person have to take two long bus rides to save a fare when two short bus rides and a subway might be quicker? Unlimited travel within two hours should be allowed regardless of the number of mass transit vehicles required.

The MTA is too concerned with losing revenue by allowing round trips on one fare, which would actually encourage ridership, recouping monies lost by allowing riders to combine errands for one fare. The vast majority of riders require more than two hours to make a round trip and would still have to pay twice to make a round trip. The MTA and its predecessors also did not allow many bus-to-bus transfers or bus-subway transfers for over 50 years, using the same excuse that too much revenue would be lost. It is time to take a new approach regarding fares.

Fare increases burden double-fare riders twice as much and route revisions requiring additional double fares are not fair. Former Limited B46 riders in Williamsburg had to switch to the slower local when SBS was introduced if they already required a transfer or else pay a double fare to use SBS. Fare-capping would help but is not a solution, even if it were done on a daily basis. It only has been proposed on a weekly or monthly basis. As more workers work fewer than five days a week at an office, weekly and monthly capping becomes less advantageous.

You also can’t take an SBS and change to a local or vice versa if you already transfer, without paying an extra fare. The MTA eliminated a long-standing policy of route modifications not requiring extra fares many years ago and now adds a third transfer only when a community protests. They also do not publicize these three-legged transfers to prevent new riders from using them.

An “improved” routing network should not require many (30% or more) to walk further and take extra buses (possibly paying extra fares) with longer trip times so that the MTA can operate fewer routes with buses saving running time to reduce operating costs. I developed an improved Brooklyn Bus Network that can be found here. In my plan, the local bus network is restructured with the major objective of increasing ridership by making the system more user-friendly.

It accomplishes this objective by making most trips possible using only one or two buses or combination of bus and subway. Service gaps are filled; routes are generally longer, straighter, and more direct, but with most buses traveling shorter distances to better increase reliability and better fit service to demand. Airport access and interborough travel are also improved. Implementation is accomplished in phases with a small investment in increased operating costs to generate greater revenue. A cost-neutral approach is wrong for a borough that has been growing significantly since 2009 in both population and businesses.

We now have a real opportunity to improve Brooklyn bus service. Let’s not waste it.

***

Allan Rosen is a retired and former director of MTA NYCT Bus Planning with three decades experience in transportation and a Masters Degree in Urban Planning. On Twitter @BrooklynBus.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.