Koch, once courted by Indian Point operator to be pitchman, explains opposition to nuclear plant

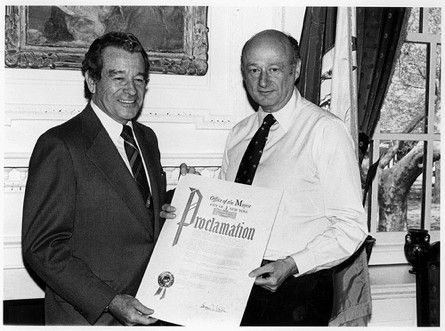

Mayor Ed Koch at City Hall, date unknown. Photo from Flickr, courtesy Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Editor's Note: A previous version of this story incorrectly referred to the findings of a draft report based on data from the New York Independent System Operator.

NEW YORK – For former Mayor Ed Koch, the turning point in his thinking about nuclear power came in March 2011 after the radioactive cataclysm in Japan caused by a crushing tsunami.

“It was incredible how the Japanese government changed its warnings from day to day,” Koch said of the response to the multiple meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi plant that became the worst nuclear disaster since the 1986 explosion at Chernobyl.

“It was clear to me that the owners of the facility were lying. The Japanese government lied at times as well. I thought to myself, what's the sense of all of this? When I put all that together I said, the hell with it. I said, why are we tempting fate? Germany will eliminate all nuclear power, and that's what we should do,” Koch told the Gotham Gazette in a recent interview.

Koch has joined a growing chorus of environmental advocates and politicians calling for Indian Point Energy Center in Westchester County to be shut down, saying the aging nuclear plant poses a danger to the 8 million people who live 24 miles to the south in New York City – especially in the wake of what was learned from the Fukushima disaster.

“We know there is no possibility of evacuating New York City,” he said. “There is no evacuation plan.”

Koch said he had been aware of the problem when he was mayor, but did nothing about it. “I thought, â€It's not my problem. It's the governor's problem and the federal government's problem.’ I should have said it was my problem. I did nothing to address it at the time. I should have.”

Koch’s turnabout on nuclear power surprised some people, not the least of whom were officials at Entergy Corp., the owner of the Indian Point nuclear plant.

The company, which has applied to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission to extend its operating license for another 20 years, said it had approached Koch two years ago asking him to be pitchman for its coolant system. Koch confirmed that he had been approached by the company.

“I said if I were to do it, they would have to provide scientific opinions that the alternative method was acceptable scientifically and would do the job, to which they agreed,” Koch told the Gazette in an email.

“At that time, I was in support of the use of nuclear energy. Fukushima had not yet occurred. However, after thinking about the offer, I turned it down because I thought it would have an adverse impact on my pro bono efforts to get support for the campaign to have the legislature accept impartial redistricting,” he continued, referring to his fight for an independent redistricting commission. “When I called to say I wouldn’t do it, I was offered $150,000. I said no, I wouldn’t do it no matter what the pay.”

Entergy, through a spokesman, denied they offered him money, instead saying it was the former mayor who brought up the subject of payment. Both Entergy and Koch confirmed, however, that the former mayor ultimately declined to promote the facility.

In a June 13 column in The Huffington Post, written with Hudson Riverkeeper president Paul Gallay, Koch noted that one of Indian Point’s two reactors faces the highest risk of damage due to an earthquake of any nuclear facility in the U.S.

The claim was first reported in 2011 by MSNBC after an analysis of NRC data -- but was later disputed by the agency itself. "Nuclear power is a complicated, technical subject, and we naturally try to simplify it to make it understandable to the general public. Sometimes, however, simplification leads to misunderstanding, and misunderstanding causes fear," wrote NRC spokesman Eliot Brenner on the agency's website. The NRC, he said, does not rank nuclear plants according to seismic risk.

Koch and Gallay also cited a 2008 study by scientists at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory that confirmed that Indian Point sits “astride the intersection” of two active seismic zones.

Koch and Gallay also point out in their article that the plant’s fire safety plan does not meet minimum federal standards.

Entergy disputes these claims. Indian Point spokesman Jim Steets said the analysis conducted by Lamont-Doherty “is not fact-based. They have expressed opinions. We are prepared to withstand an earthquake 100 times greater than what would have been experienced in the Indian Point area.”

But he also added: “There is some evidence that earthquakes (in the area) could be stronger. We are looking into that.”

Steets said the cooling system for the Daiichi plant’s reactors was damaged by the tsunami, not by the earthquake that preceded it. But the results of an independent investigation commissioned by the Japanese parliament say otherwise.

“A conclusion denying quake damage cannot be drawn,” said the report released last week. “The recorded seismic motion at Fukushima Daiichi exceeded the assumption of the new guideline. It is clear that appropriate anti-seismic reinforcements were not in place at the time of the March 11 earthquake.”

As for the plant’s fire plan, Steets replied: “The issue has been resolved to NRC’s satisfaction. A lot of the remedies have been completed; others are being engineered and resolved.”

But it is Entergy’s evacuation plan for the area around Indian Point, in the case of an accident, that particularly resonates with the former mayor. The company confirmed that the plant’s “emergency planning zone” encompasses the 10-mile area around Indian Point and makes no provision for New York City.

But Steets said the flooding that destroyed the Daiichi plant’s reactors was impossible at Indian Point’s location, and that the design of the plant negated the possibility of a massive explosion, such as the one at Chernobyl.

These factors would give the city time to mobilize in the event of an accident, he said. “An emergency that necessitated a massive evacuation would not occur instantaneously,” Steets said.

The city’s Office of Emergency Management has designed an “area evacuation plan” that could be used in the event of a nuclear accident, a spokeswoman said. The plan is currently designed to evacuate one neighborhood or swaths of the city in coordination with transit agencies.

But OEM spokeswoman Judith Kane said it could be used to evacuate the whole city “in theory,” though she said it was “hard to imagine” such a scenario. She said that in the case of a nuclear emergency, the city would likely rely on plume modeling to track the spread of radiation and make decisions.

The disaster in Fukushima, she said, encouraged the agency to coordinate more closely with its counterpart in Westchester County. “It's inevitable with any disaster,” she said. “When something happens in another part of the world, it always raises the question, what would happen in New York City? Is this good enough? Does it cover the worst case scenario?"

After the disaster in Fukushima, a 12-mile exclusion zone was established around the Daiichi plant and approximately 170,000 residents were evacuated. Persons living 12 to 24 miles from the plant were first asked to remain indoors, and then evacuations were initiated for these areas as well.

Koch said that if he were in the current mayor’s position he “would be putting the city’s experts together preparing a memo of opposition to the renewal application.”

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has spoken in favor of renewing Indian Point’s licenses, and has sharply rejected the idea of closing the plant.

“Well, if you closed Indian Point down today we’d have enormous blackouts. There is no alternative to the energy that we get from Indian Point. Four or five years from now that probably is not going to be true,” Bloomberg said in June 2011. “All types of power generation have risks and nuclear hasn’t killed anybody.”

In their article, Koch and Gallay said the New York metro area does not require Indian Point for its immediate power needs, arguing there is enough surplus power available to close the plant now and still meet regional demands through 2020.

A study commissioned by New York City confirmed that 2011 data from the New York Independent System Operator showed sufficient power through 2020.

But the final version of the report by Charles River Associates adjusted the ISO's forecast of 91 percent energy efficiency penetration – the degree to which energy efficiency targets have been met – saying that a 50 percent rate was more "realistic."

After adjusting the ISO data, the final report argued that the grid would fall short in the summer of 2016. Charles River Associates also raised questions about the reliability of power distribution without Indian Point. And their study estimates that the city's consumers would see their energy bills increase by 5 to 10 percent if Indian Point were to close.

A separate study, by Synapse Energy Economics, found that the cost increase to consumers might actually be far less, only 1 to 3 percent.

Koch said that when challenging a nuclear power plant “local governments feel powerless. The Congress has taken most of the power of local governments away and made it solely a function of a federal agency.”

A case in point is Vermont’s attempts to close Vermont Yankee, an Entergy plant situated on the Connecticut River, which have been unsuccessful to date. A challenge to Vermont Yankee’s license renewal failed last month in federal court.

Phillip Musegaas, director of Riverkeeper’s Hudson River Program, said that the debate about keeping Indian Point open boils down to one question: “If you don’t need the power, why take the risk? Its location is fundamentally problematic.”

When asked what he believed was the fundamental obstacle to closing Indian Point, Koch responded: “It’s called money. People invested billions in these plants … and are going to fight tooth-and-nail to protect these investments.”

NRC public hearings on Entergy’s application for renewal of Indian Point’s licenses are set to begin in October, though seismic risk and evacuation planning won’t be evaluated as part of the process. The reactors are currently licensed to operate until 2013 and 2015, respectively.

Challenges mount at Hudson River Park

Photo courtesy of the Hudson River Park Trust

It's the 50th anniversary of the building complex at Hudson River Park's Pier 40, and the aging, dilapidated commercial structure is in peril. The roof of the building's parking garage is falling in and the pier's support pilings are disintegrating as marine worm borers feed on them. The building itself has exposed wiring, rusted metal and a leaking ceiling. The halls are covered in graffiti.

Still, Pier 40, which is used daily by both ball clubs and commuters despite the need for emergency repairs to its pilings and roof, is in significantly better condition than nearby Pier 54, which can't currently support the weight of the public and is inaccessible.

These are just some of the growing problems at the Hudson River Park, a 550-acre park along Manhattan's western edge that draws over 17 million visitors a year.

At a recent meeting of the Hudson River Park Trust that drew nearby residents and environmentalists concerned about the construction of a natural gas pipeline that would run under the greenway, officials said the cost of making the repairs continued to balloon, with the work needing to overhaul Pier 40 alone estimated at $120 million.

The challenges have sent officials scrambling to find ways to raise revenue, floating several options including residential and retail use and a long-shot proposal to construct a Major League Soccer stadium on Pier 40. But any option would need to support the long-term financial health of the piers while also acquiescing to some of the community's demands.

Officials also said that the constraints of the Hudson River Park Act, created by New York state to establish the the greenway in 1998, limited their options and might need to be revised.

The park itself is only 80 percent complete, said Arthur Schwartz, a member of Community Board 2. At the same time, government funding has been cut from about $20 million a year to $6 million. The state has promised to fund the park to completion.

At the recent meeting, Trust president Madeline Wels said the urgency of the repairs and size of the costs calls for “creative” solutions that might well require an amendment to the Act. Emergency repairs alone will come to $80 million over the next 10 years, far exceeding both their reserve fund of $25 million and expected revenue.

“The park's intention was to be self-sustaining, and there's enough money for regular maintenance, but not for capital maintenance,” Wels said at the meeting. She noted that badly needed infrastructure repairs, some of which were caused by damage from Tropical Storm Irene and some from the marine worm borers “weren't anticipated.”

The Trust had expected a private developer to fix the problems at Pier 40, but no private developer has come forward to lease the property, and now the park is faced with covering the cost themselves.

Potential development proposals were analyzed by Tishman Construction and their findings were also presented at the meeting. Of these, the prospect for the most revenue, explained Jed Howbert, a Tishman representative, includes retail and residential use, ideas that officials acknowledged are unpopular with community members in the area. Regardless of what is developed, the Trust maintained that 50 percent of the park on Pier 40 would remain open space.

The proposal to create a Major League Soccer stadium on the pier had not been received in time to be included in Tishman's study, however, and Schwartz said questions remain regarding the impact on residents, as the stadium would bring in about 25,000 fans per game or event. The impact of a stadium would not be known until an official request for proposals is distributed, said John Kelly, a spokesman for the Trust.

If residents want to hear different proposals, Wels said at the meeting, the first step would be to amend the Act and extend the 30-year lease limit that is currently in place, a restriction that makes some development ideas untenable. The Trust would also like to see an amendment permitting the ability to bond for more money.

“We're trying to help the Trust sustain itself by amending the law,” said Wels. “We will get better proposals, too.”

But some residents at the meeting said any change to the law was going too far. Alison Tupper, a resident of the West 40s, acknowledged the dire budget hole, but said the real value of the greenway was its function as a park. “Changing the law could open the park to unintended consequences,” she said.

Assemblywoman Debra Glick, an outspoken critic of some of the Trust's proposals, argued that deteriorating conditions were being used as a reason to drastically and quickly rewrite the Act's restrictions before the close of the current legislative session.

“The Assembly has asked the HRPT for what their immediate need is so we have time to review things,” she said. “I don't think you make good decisions in crisis mode.”

The most urgent repairs are expected to cost approximately $15 million, she said, with $5.8 million going to Pier 40's most crucial repairs. Kelly said repairing the entire roof will cost $30 million, with an additional $90 million needed for repairing pilings.

“I'd like to see the city and state provide that emergency infusion to make those repairs right now in order to buy enough time for a more thoughtful discussion,” Glick went on.

She said more time was also needed to get comments from the public on the proposal to change the Act that created the park, considering the “significant changes” being presented. "It took 3 to 4 years to draft [the Act] after literally scores of public meetings," she said.

Glick described the meeting as “severely lacking” in public involvement, calling it little more than a presentation of the options the Trust seemed most inclined to promote. In fact, following the Trust's presentation, additional Trust members, largely repeating what was already said, were given the first opportunity to speak at a meeting with a limited time frame for public speakers.

The Trust insisted the meeting was a culmination of six months of “intensive exploration” with elected officials, community boards, and active community groups. Should the Act be amended, there will be a “built-in time for public feedback” following any plan to move forward with a development proposal.

Brad Hoylman, the Community Board 2 chair, said he was particularly frustrated by what appeared to be the city's apathy to the park's problems. Hoylman noted that Governor's Island would be receiving $260 million in city funds, a park used five months a year, while Hudson River Park is "used everyday of the year." He added that the city had provided money for the East River esplanade as well.

“We as west-siders have to ask, why aren't we getting a share of that money? They made plenty of money off of us,” he said.

Representatives for the city didn’t respond to requests for comment. The mayor has called Governors Island “the centerpiece of our efforts to revitalize New York City’s waterfront.”

___

Matt Hunger, a Brooklyn-based freelance journalist, writes on everything from municipal issues to the arts and sports. He can be reached at matt.hunger(at)gmail.com.

Exclusive: Proposed policy would allow industries to self-audit pollution-generating activities

Industries that use pesticides, treat wastewater and store hazardous chemicals could have penalties for breaking pollution laws reduced or waived if they agree to self-report violations under a policy being considered by New York’s leading environmental regulator.

Any entity that enters into an agreement with the state Department of Environmental Conservation to self-audit would also “not be prioritized for inspection during the audit period,” stated a draft of the proposed policy obtained by the Gotham Gazette.

The DEC regulates sources of air and water pollution, including private industry, agricultural uses, and municipal facilities like waste transfer stations and sewage treatment plants. It is responsible for enforcing over 40 New York State environmental laws and over 50 federal laws, including provisions of the Clean Air and Clean Water acts. The agency would also be charged with regulating hydraulic fracturing in the Marcellus Shale.

The self-audit policy, described in a draft document dated May 14, would apply to any private business or public entity, including federal, state and municipal agencies and facilities, which are regulated under state environmental law.

A self-audit, however, “is not required for disclosure and may not be warranted in certain circumstances,” the document states. Environmental violations involving suspected criminal conduct would not be eligible for a penalty waiver.

Further, the DEC would conduct an inspection if it receives “a complaint concerning the regulated entity or have reason to believe that a violation has occurred resulting in serious actual harm.”

DEC Executive Deputy Commissioner Marc Gerstman said the goal of the proposed policy was to promote compliance with environmental laws.

“Nobody is being given a free ride or a ticket to pollute,” he said. Instead, the policy encourages companies to come forward when something goes awry. “If a company has a violation that they want to disclose, [they] have some comfort level that we will not impose penalties.”

The draft of the policy was distributed in the DEC’s central and regional offices for internal review. DEC officials also said the agency had “held stakeholder meetings with environmental groups, municipalities and businesses to get their input on developing a self-audit policy.” More meetings were planned, they said.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency would also have to clear the new policy. A spokeswoman for the agency said they were unaware of the proposed policy. The DEC said it had attempted to contact the EPA and would discuss it with their federal partner before it is finalized.

Read the draft DEC document below

Too unwieldy to implement?

The proposed policy has already stirred up some concern among current DEC employees who worry that it will be too unwieldy to implement given the agency's resource constraints. One worker who has conducted inspections and reviewed the document told the Gazette that “the glaring issue is who is going to review all these audits.”

“We don't have resources to keep up with normal enforcement,” said the employee, who was not allowed to speak about the policy publicly and spoke on the condition of anonymity. “If the audit policy becomes a priority, then enforcement becomes secondary.”

Since 2008, the agency has lost almost 800 employees, bringing staffing levels to their lowest point in over twenty years. Meanwhile, federal financial support for the DEC has steadily declined and the agency has become more reliant on New York State tax dollars and revenue from fees and penalties.

“Resource limitations” and “the high volume of activities potentially affecting human health and the environment as well as practical constraints” in part led the agency to develop the proposed self-audit policy and other “auxiliary strategies,” the draft document stated.

DEC spokeswoman Emily DeSantis said the policy would alleviate some pressure on personnel. “As more entities within the regulated community adopt approaches to assess environmental performance on their own, the policy will allow DEC to focus its enforcement efforts on the truly bad actors,” she said.

The Debate Over Self-Audit Agreements

Environmental self-audit and voluntary compliance policies have been used by both the federal government and sporadically at the state level since the early 1990s. The DEC’s newly proposed self-auditing program would greatly expand the agency's current use of self-reported information, representing a major shift in the state’s approach to environmental protection.

The proposed policy enables companies and other entities to enter into self-audit “agreements” with the DEC. These agreements can be comprehensive, covering all environmental laws and regulations applicable to a facility, or limited to a portion of those requirements. Companies and other regulated entities that commit through a self-audit agreement to minimize their impact using “environmental management practices and pollution prevention systems” would be offered a variety of incentives.

The incentives are still being developed but they could include public recognition of the company’s efforts and access to technical assistance services, according to the draft document. Perhaps more importantly, they could include additional assistance with penalties and timeframes for correcting violations.

Some critics argue that such self-auditing programs could lead to less frequent inspections, erode defined missions for state regulators and provide a shield for polluters against environmental enforcement and public oversight. Others said enforcement should be the focus of regulatory efforts.

Robert Sweeney, the Democratic chair of the state Assembly’s environmental conservation committee, said he was skeptical of the proposed policy, which he had not seen until it was provided to him by the Gazette.

“A better option would be to consider beefing up enforcement, which would pay for itself,” he said. In a subsequent email, he added: “It may be old-fashioned, but to keep people honest you need cops on the beat.”

Self-audit agreements could also deal a blow to transparency and acountability, said Bill Wolfe, director of the New Jersey office of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. “There are no public hearings… no discoverable documents,” he said. “The audit becomes a way to stay private.”

But others saw a benefit to the policy. Richard Schrader, the New York State legislative director for the National Resources Defense Council, said a self-audit policy “make sense as one of the tools for environmental compliance.” But he said such a policy requires “great care and caution … [It] can’t be a substitute for ensuring that the DEC has adequate enforcement staff, and they still have to pursue full-compliance in an aggressive fashion.”

Darren Suarez, the government affairs director for the Business Council of New York State, said self-audit agreements could be beneficial to both the companies themselves and to “the goal of reducing degradation to the environment.”

“A self-audit helps to identify areas where an institution may not be handling materials as well as they would want to,” he said, and later added: “If they can come into compliance, that’s the big incentive.”

DEC spokeswoman DeSantis said the program would encourage “comprehensive company-wide audits and best management practices, designed to identify and correct violations without fear of significant penalties.”

“In the end, companies and municipalities that have strong systems in place to ensure environmental compliance will prevent violations down the line,” she said.

Learning From Experience

A “voluntary compliance” policy was previously attempted by the DEC in the mid-1990’s under then-Commissioner Michael Zagata. But one retired DEC staffer with knowledge of the enforcement process said the agency’s personnel grew reticent to follow up on reports of violations after the policy was in place.

Paul Gallay, a DEC attorney from 1990 to 2000 and now president of Hudson Riverkeeper, said of the Zagata period: “The hidden message was, â€We don’t have to enforce the way we used to.’”

Zagata, who is now the president and CEO of the Ruffed Grouse Society in Pennsylvania, said he could not remember if there was a written policy with clear parameters. But he said that voluntary compliance was something he was trying to push as a philosophy throughout the agency.

"Voluntary compliance, with the understanding that if you don't do it, there's a stick on the other side of the fence, is doable,” he said, but added that the agency would still need enough workers to verify noncompliance.

DEC administrative hearing records for a case settled in 2005 involving a gas station with registration and safety violations reference a backlog of enforcement cases due to the agency’s “voluntary compliance” program.

The case, which focused on the gas station’s underground tanks, took over a decade to resolve and hinged on whether the tanks were being tested for leaking that could seep into wells or other underground water sources.

“Although the tanks were due for testing in October 1992, DEC staff did not inspect the facility or take action to bring it into compliance with the testing requirement until June 2002,” hearing records stated. “This was part of an ongoing effort by DEC staff to reduce a backlog of overdue registrations and tank tests that had accumulated while the Department was pursuing a policy of voluntary compliance.”

Other states' experiences

As New York weighs a possible self-auditing policy, New Jersey is also re-visiting the idea after an earlier proposal was struck down. Meanwhile, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection has used a form of self-auditing in its Waste-Site Clean-Up program since 1993; it has considered expanding the policy into wetlands management but has not made a final determination.

Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility released a 2008 press release charging that the “failure rate” among companies who self-audited using private licensed consultants was found after a state review to be 70 percent (21 of 30 sites).

Paul Locke, director of response and remediation for the Bureau of Waste Site Clean-Up at the Massachusettes DEP, rejected the criticism. “That is not representative of the universe of submittals of site clean-ups that we get,” he said.

He argued that privatizing aspects of environmental auditing and oversight can be appropriate in contexts where licensed professionals are engaged in well-defined tasks. “You have to set up the system so that they are checking in along the way -- you have multiple checks and balances. It’s not as clear-cut as the Wild West of self-auditing,” he said.

Kyla Bennett, who runs the New England PEER office and worked for the EPA for ten years, said she believes there is an inherent conflict of interest in allowing private companies to pay for environmental audit services as opposed to relying on public enforcement.

“Is it a risk? Absolutely…. You can skew things in one direction or another. It happens all the time. The Massachusetts DEP doesn’t have the money to go after licensed professionals, let alone go after violators,” she said.

Stretching Resources

The policy draft says self-auditing will “supplement” existing DEC environmental enforcement activities. How well environmental enforcement is currently working and the DEC’s ability to keep up with inspections has been a subject of scrutiny, especially given the DEC’s loss of staff.

Commissioner Joseph Martens told the Gazette in March that the DEC will not see an increase in staff “anytime soon,” due to the state’s fiscal situation. The draft’s reference to DEC’s resource limitations raises the issue of how the agency has searched to find ways to meet state and federal mandates.

A DEC employee with knowledge of the state’s petroleum bulk storage program, which regulates oil storage facilities of over 1,100 gallons typically found in gas stations, medium to large industrial businesses and public buildings, said private contractors have been brought in to help with the inspection backlog because the program is so shortstaffed.

The program is run in conjunction with the federal EPA. The employee, who was not allowed to speak publicly about the program and did so on the condition of anonymity, explained: “This year, over 24,000 PBS sites have overdue tank registrations. Historically we would send out notice of violation letters and attempt to get a penalty. DEC would get responses and that would be the ones we would work on. The ones who did not respond was a low priority. Think of the volume. No way can the DEC handle that volume effectively, not then and not now. We are trying to prioritize the volume of non-compliance. But I see this as a failure in the [PBS] regulation and its attempt to prevent oil spills.”

The DEC disputed the employee’s claim, saying that only 4,600 PBS registrations were more than 90 days overdue. Fewer than 600 are less than 90 days overdue. The DEC said most of the overdue regustrations were heating oil tanks, “which are generally overdue because they have been sold or have changed management companies.”

“DEC has and continues to promote compliance and do enforcement as necessary for these overdue registrations,” said DeSantis, the agency spokeswoman. “This enforcement is done every year and has been ongoing since 1997 when we had more than 8,000 facilities overdue for registration.”

The DEC has acknowledged that they stopped performing effluent sampling as a regular part of the State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System inspection program in fiscal year 2010-2011 after significant staff loss. Any facility that discharges into surface water needs a permit, including manufacturers, power plants and sewage treatment plants. The DEC uses self-reported data from regulated pollution sources as part of the SPDES program.

According to Environmental Advocates, a watchdog group that monitors the DEC, in 1990, the DEC sampled effluent 1,113 times to verify polluters’ reports.

In 2008, the DEC took 112 samples, a 94 percent decrease. The DEC said the sampling is not required by law. “This information continues to be self-reported by the permitees,” the agency previously told the Gazette.

Conclusion

The New York DEC is completing an internal review of the self-audit policy before introducing it more broadly. The agency has not indicated whether the policy would be tested out in one division first, or if it would apply to all of DEC's enforcement work. New York State Legislative approval for adoption of the policy is not required. The DEC’s Gerstman noted that the agency is “coordinating with the federal EPA as a partner.”

Suarez, of the Business Council, said the right questions to be asking are “what do you ultimately want to see and how do we get there? And (can this) allow businesses to stay here?”

Hudson Riverkeeper’s Gallay said there was a way to balance environmental law with business interests while also enforcing penalties. “When I worked for the DEC, we took great pride in bringing companies back into environmental compliance and economic health. You don’t need penalty forgiveness policies to do that,” he said.

The DEC has sole discretion to select eligible businesses and other entities for participation in self-audit agreements, the draft document states, and to exclude “bad actors” that have a history of non-compliance. Regulated entities that own or operate multiple facilities can still be eligible even if one of their facilities is under investigation.