Bloomberg Moves to Change the City Charter, But How?

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, making good on a promise in his 2008 State of City speech, announced on March 3, the creation of a charter revision commission. The mayor called for a comprehensive look at the structure and operation of city government, charging the commission with “examining the changes made by the 1988 and 1989 Charter Revision Commissions, and other subsequent changes, in light of the lessons learned over the past two decades and the new challenges and opportunities that have since arisen.” The mayor also charged the commission with conducting an extensive outreach campaign: “Every issue will be on the table, and every voice will be heard."

The mayor appointed Matthew Goldstein, chancellor of the City University of New York, to chair the commission, and John Banks, former chief of staff to New York City Council Speaker Peter Vallone, to serve as vice chair. The other 13 members included business, community and religious leaders, sitting and former government officials, educators, mayoral staffers and political operatives. Bloomberg also announced that the Citizens Union would conduct its own review of the charter, which the mayor said would be a great resource for the commission. (Citizens Union's sister organization is the publisher of Gotham Gazette.)

The commission would be the fourth under Bloomberg and the seventh since the last comprehensive charter review — the commissions appointed by Mayor Ed Koch in 1988 and 1989. Bloomberg had announcedin his Jan. 17, 2008 State of the City that he would appoint a commission, which, he said, would "conduct a top-to-bottom review of city government over the next 18 months."

But the commission never happened. The reason: Bloomberg wanted to run for a third term in 2009. Had a commission placed on the ballot an extension of term limits, the voters would have likely voted it down, as they had in 1996. Polls in 2008 showed widespread support for term limits and no enthusiasm for loosening them. Instead, term limits would have to be changed legislatively by the City Council.

Lauder Turnaround

In his effort to extend term limits, Bloomberg needed to at least neutralize Ron Lauder. Lauder funded the initial 1993 charter change establishing term limits and the defeat of a proposal to extend the cap to three terms in 1996. So in fall 2008, the mayor made an http://www.villagevoice.com/content/printVersion/1393325 offer that Lauder chose not to refuse — Lauder would support a "one time exception" to the two-term limit in exchange for a seat on a charter commission formed after the 2009 elections.

But Lauder was not named to the 2010 commission. It appears that Lauder, after conversations with the mayor, had decided that he would become a lightning rod for attacks on term limits, and that he could do more to restore the earlier limits outside the commission. He could once again use his personal fortune to contest any action by the commission that he might find objectionable. Lauder’s absence would also preclude charges that Bloomberg’s agreement with Lauder was a bribe. Indeed, NYPIRG and Common Cause had filed a complaint on Oct. 8, 2009 with the city's Conflicts of Interest Board charging Bloomberg with violating the city's ethics laws when he pledged to put Lauder on a charter commission in exchange for his support for the term limits extension. Two members of City Council -- Bill de Blasio, now the city's public advocate, and Letitia James filed a separate complaint with the board. (The board, appointed by the mayor with the advice and consent of the City Council, did not find a conflict.)

Changing the Charter

The charter is the governing document of the city; it establishes the framework within which the city governs itself. It defines the organization, power, functions and essential procedures and policies of the city's political system; it establishes the authority and responsibilities of the city's elected officials. It also lays down the basic structure of the city's finances. It is a large document (currently 356 pages), packed with organizational minutiae, much of which belongs in the Administrative Code.

Charter adoption and revision in cities in New York State is governed by Article 4, Part 2 of the Municipal Home Rule law. The law provides for the appointment of a charter commission in New York City through City Council action, a petition followed by a referendum approving the creation of a commission or mayoral action. Mayoral action takes precedence over the other two, letting mayors use commissions as political tools.

Not all charter revisions have to come from a charter commission. They can be placed on the ballot through passage by the City Council or through petition by at least 50,000 registered to vote. The amendment establishing term limits was enacted by popular vote in 1993 after a petition drive; The City Council placed the unsuccessful 1996 proposal to extend the number of four-year terms from two to three before the voters.

The charter is a "fluid" document, which is often amended, sometimes by city voters, most frequently by local law -- as the council did in its October 2008 vote to revise the charter's term limits provision. A popular vote is required if the amendment relates to the manner of voting for elective office (not the term or tenure of those offices), creates a new elective office or redistributes power.

New York's first City Charter was drafted by a city commission in 1936 and implemented in 1938. Prior to the 1924 Home Rule amendment to the State Constitution, city charters were amended by special acts of the legislature. Commissions in 1963, 1975, 1988 and 1989 proposed significant revisions to the charter, which voters then adopted.

Charter commissions are charged with reviewing the entire city charter, though mayors through their "charges" broadly set the commission's agenda. The commission must produce reports, including proposals to adopt a new charter or revise the existing one. All proposals must be adopted by the city's voters not later than the second general election after the commission's appointment. The recommendations of the commission can be voted as one omnibus measure (as in 1989 and 2001) or as separate proposals (the other post 1989 commissions).

The Koch and Giuliani Commissions

The recent history of charter commissions shows two very different approaches, one by Koch, the other by Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. Koch, responding to the Supreme Court's decision declaring the Board of Estimate unconstitutional, created a commission in1988 to come up with a new structure for city government. The commission, with highly regarded, independent chairs Richard Ravitch (now lieutenant governor) and Frederick Schwarz and commissioners of high quality, had an experienced, knowledgeable professional staff, which produced comprehensive studies of electoral systems and institutional structures and processes. It consulted widely with government officials, civic leaders, advocates and community members, holding dozens of public hearings throughout the five boroughs.

The process took three years, employed 52 full-time staffers and entailed 141 public hearings over two years. The commission, proving itself a medium of positive, meaningful change, created the system New York has today, with a 51-member City Council, a public advocate elected city wide and limited roles for the borough presidents.

Giuliani, on the other hand named three charter commissions, each chaired by close associates, with long-time friends or political associates as commissioners. His consultations and public hearings were largely perfunctory.

The commissions were, Giuliani frankly admitted, political tools. The Municipal Home Rule Law Section 36 (5)(e) provides that the placement on the ballot of a valid proposal initiated by a charter revision commission will "bump" other referenda off the ballot. The courts have affirmed this provision even when there is recognition that a charter revision commission has been created expressly to keep other proposals off the ballot. There is currently a bill in the State Assembly (A6019) which "eliminates the rule that provides that whenever a city charter commission puts a proposal on the local ballot,all other local referendum proposals are barred from the ballot."

In 1998, the mayor used charter revision as a political maneuver to block from the ballot a referendum proposed by the City Council on whether the city should build a West Side stadium to replace Yankee Stadium. A year later, he created a commission to change the city's succession procedure, largely to stop Public Advocate Mark Green from becoming mayor if Giuliani left his job for the U.S. Senate. A 2001 commission dealt with minor administrative changes that could have been dealt with by local law rather than constitutional change. In each case, the mayor got what he wanted from the commission, though the voters largely rejected the recommendations. (For more on Giuliani's specific proposal, see Charter Commissions Since 1989.)

Bloomberg's Commissions

Bloomberg created three prior commissions -- in 2002, 2003 and 2005 -- his approach has been a hybrid of Koch and Giuliani policy concerns, political motivation, and commission personnel. He has been Koch-like in selection of commissioners and chairs (though "the fix was in" on non-partisan elections, and the chair of the 2005 commission, Ester Fuchs, had been serving as a senior advisor to Bloomberg). But the mayor was Giuliani-like in his creation of the 2005 charter commission as a tool to forestall placing a class size proposal on the ballot via referendum.

The commission that Bloomberg appointed in 2002 represented Koch's approach in the selection of commissioners and the chair, Robert McGuire. Also, the issues addressed, the nature of the city's voting system -- the mayor had charged the commission with examining nonpartisan balloting -- and succession to the mayor, were significant. However, the press and civic groups such as Citizens Union and the Women's City Club roundly criticized Bloomberg for the short timetable for crafting the recommendations-- far shorter than any charter commission in the prior 70 years.

The McGuire Commission proposed one ballot measure that changed mayoral succession from the public advocate being mayor until the end of the former mayor's term to serving as interim mayor only until a special election to be held within 60 days of a vacancy (what Giuliani had wanted but without the enmity toward the public advocate that Giuliani had for Mark Green). City voters adopted the change. The commission, like those in 1998, 1999 and 2001, chose not to place nonpartisan balloting before the voters.

The mayor was determined to establish nonpartisan elections for city offices and in March 2003, announced the creation of the fifth charter commission in six years, charging it with considering nonpartisan elections for all city officials and putting such a proposal on the November ballot. He named Frank Macchiarola, the president of St. Francis College, chair. Macchiarola announced that a proposal recommending nonpartisan elections would be placed on the ballot in November before any other commissioners were named.

Non-partisan elections and the commission's handling of the issue generated much opposition -- from often-strange political bedfellows. The commission never adequately addressed the substantive critiques of non-partisan elections and never explored the possible consequences of the system it ultimately proposed to the voters. Indeed, the system that the commission proposed in September was the system in place in Jacksonville, Fla., which had limited experience with it and, unlike New York, did not have public campaign financing or term limits. There was just not enough evidence to make major changes in the voting system, irrespective of calculations of political wins and losses. Voters overwhelmingly rejected the proposal, despite the fact that the mayor bankrolled the pro-change effort with $7 million of his own money. (Surely, this was the first time that a sitting chief executive funded a constitutional change that would benefit him.)

In 2005, Bloomberg, like Giuliani, used the charter revision process as a political weapon. Proponents of smaller class sizes gathered far more petition signatures than required to place the matter on the ballot. The mayor and his Department of Education opposed setting rigid limits and so sought to preclude the referendum from appearing on the ballot by promoting charter revisions of their own. Fuchs, a Columbia University professor and senior policy advisor to the mayor, chaired the commission. It followed the Koch model: well-respected independent commissioners, wide public outreach and professional staff research. The commission placed "two rather obscure measures" on the ballot. One established ethics rules for administrative hearing officers; the other would add financial management requirements into the charter. Voters approved both.

What Will/Should the Commission Do?

Overall, in the 20 years since the 1989 restructuring, the number of charter changes approved by the public has been few and the substance narrow. In 2010, the charter remains essentially the framework established in 1989. So what can we expect to happen with the new charter commission? What should happen? Will it actually conduct the sweeping, comprehensive review and put forth the substantive recommendations that the mayor promised and the 1988-89 commissions delivered? Or will it focus on just a few matters?

Charter revision raises two sets of questions: those on process and structure, and those on possible, needed or likely substantive proposals. Among the process and structure questions: What should be guiding goals and principles of the commission? What makes a "good" commission and commissioners? What is desirable staffing, budget, timeframe? What has been, is and ought to be the role of the mayor?

Any rigorous review of today's charter must begin with the 1989 commission: What has worked? What hasn't? Why? How do we "fix" it? Any unwanted consequences lurking? A comprehensive review in 2010 would likely be framed by three broad themes, as it was in 1989: centralized power vs. local advice and consent; governmental checks and balances (essentially, how to contain the power of the mayor) and expansion of an informed electorate.

What is certain to be addressed by the 2010 commission is term limits. The 2010 charter revision commission owes its existence to term limits -- or rather to their extension. Without the council overturning two prior citywide votes, Mike Bloomberg would be writing checks from his foundation, and there would be no Goldstein Commission. The commission could recommend elimination of term limits entirely, a return to the two-term limit for all city elected officials, making Mike Bloomberg the "one time exception," or conclude that the current three-term limit or a variant is best. Should changes to term limits be subject to mandatory approval by voters?

Chancellor Goldstein, on being named chair, stated, "Certainly term limits will be something we will consider but beyond that I don’t want to speculate."

But speculation is in order.

Given that land remains one of the principal stakes in the New York political game, zoning and land use policies -- less glamorous but with far greater effect on the city and the well being of its neighborhoods and residents -- will very likely be a subject of commission discussion. The Bloomberg administration and real estate developers see the current city land use policies, notably the Uniform Land Use Review Process or ULURP, as inefficient, time consuming and often wrong-headed. They would like to see it "streamlined" with such changes as shorter time frames for review and elimination of some steps. Others want enhanced purview and greater powers for community boards and City Council on zoning and land use matters. The commission could also look at the composition and authority and processes of the City Planning Commission and the Board of Standards and Appeals.

Among the other topics that a comprehensive commission may address (with different degrees of likelihood) are:

- the powers and purviews of the mayor, City Council (such as increasing the size of the council; making it a full-time body with limits on earned outside income; enhancing its budgetary role), comptroller (whether the comptroller should have power to establish or sign off on revenue estimates), public advocate (retain or eliminate the office; whether to give it a dedicated funding stream or subpoena power), borough presidents (retain or eliminate; maintain, reduce or enhance authority in areas such as in land use decision making and capital planning and budgeting), and the advisory community boards (providing an enhanced role in planning/land use; providing them with professional support);

- voter participation, such as non-partisan voting, runoffs and immigrant /non-citizen voting;

- ethics, including appointments to and the purview and procedures of the Conflict of Interest Board, and oversight of lobbying activities;

- campaign finance (changes necessitated by the Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United v. the Federal Elections Commission; elimination of public funding in non-competitive races; the disclosure of private spending by self-funded candidates);

- procurement (enhanced bidding and contracting oversight by comptroller or City Council)

- charter content (such as moving much of charter to Administrative Code)

The public advocate's position and the role of the borough presidents have long been subjects of conversation. In October, at a Staten Island Advance editorial board interview, Bloomberg said that eliminating the public advocate’s office could be on the table. He also said that while he might be open to giving borough presidents a different role, he was not prepared to give them more power by taking it away from City Council.

It is unlikely that a charter commission would move to further weaken or eliminate the public advocate or the borough presidents. After all, the closeness of Bloomberg's November win resulted from public disenchantment with Bloomberg's term limits end-run. Undercutting potential sources of opposition would only reinforce the view of him as an "imperial mayor."

Non-partisan elections may once again be on the table. It's been reported that in spring 2009 when he was seeking the Independence Party endorsement, Bloomberg told party leaders he was open to again looking at non-partisan elections. Dissatisfaction with the current runoff system for citywide officials (if no candidate gets 40 percent, the top two finishers compete in a runoff two weeks after the primary), might lead to study of alternatives such as Instant Runoff Voting.

Time and Money

For the Goldstein commission to act in any meaningful way to meet the mayor’s charge of a comprehensive charter review where "every issue will be on the table" will be close to impossible in the less six months that the commission has to make recommendations to be placed on the ballot for this November. (Proposals must be submitted 60 days before the November election). It is certain that the short time frame will generate much concern and criticism.

Chancellor Goldstein stated that he envisioned that the commission’s work would probably last until 2011 but that a few recommendations would be made early enough that they could be placed on the ballot this year. However, under state law, charter commissions expire once the balloting on their recommendations takes place. So the Goldstein Commission would go out of business on Wednesday, Nov. 3, 2010. The mayor could then create a commission with the same or similar membership that could place recommendations on the Nov. 2011 ballot. This happened in 1988 and 1989. The 1988 Ravitch Commission expired after the 1988 general election. In 1989, Mayor Koch appointed a commission with Frederick Schwarz as chair (Ravitch was running for mayor in the Democratic primary). That commission went out of business after the 1989 November elections.

And then as always with this mayor, there is the question of funding: Is Bloomberg going to put money into it as he did $7 million in 2003 in the nonpartisan election vote? Will he get better returns?

Warning: Expect the Unintended

Whatever specifics it considers, the 2010 commission in its deliberations and recommendations should beware the law of unforeseen and unintended consequences: Actions of people -- and notably of government -- will always produce some unintended, unanticipated and usually unwanted consequences, and these effects can be more significant than the intended effect.

Jimmy Flannery, the Chicago sewer inspector, machine ward heeler, sleuth and protagonist of Robert Campbell's crime series, has a warning in The 600 Pound Gorilla for those who would tinker with a city's government: "A thing like a city government is like a tower built out of match sticks. It stands so rickety you think one breath'll knock it flat. Somebody decides to fix it. Take out this rotten beam and that rotten brick. Chop out a floor, pump out the basement, add a garden room. Then everybody acts surprised when it comes crashing down."

Douglas Muzzio is a professor of public affairs at Baruch College and co-director of the Center for Innovation and Leadership in Government. He co-authored (with Professor Gerald Benjamin) the 1988/1989 charter revision commission's study on the City Council and alternative voting systems. He was an expert witness before the 2003 charter commission on nonpartisan elections and will serve on the recently created Citizen Union's panel to review the current charter.

For a comprehensive review of the 1988 and 1989 charter commissions, see Frederick Schwarz and Eric Lane, "The Policy and Politics of Charter Making: The Story of New York City's 1989 Charter, "New York Law School Law Review," Vol. XLII, 1998; for an examination of those commissions and the six subsequent ones, see Ida Cheng, Jenifer Clapp, Arianne Garza, Liz Oakley, and Gregory Wong, "NYC Government: 1989 and Today," Citizens Union, April 27, 2007.

Charter Commissions Since 1989

|

Mayor |

Date |

Chair |

Ballot Proposal(s) |

Voting Result |

|

Rudolph Giuliani |

2/19/98 |

Paul Crotty |

Revamp city campaign finance law and bar corporate donations |

adopted 60-40% |

|

Giuliani |

6/15/99 |

Randy Mastro |

1. Impose a cap tied to the inflation rate on city budget increases. |

rejected 76-24% |

|

Giuliani |

7/15/01 |

Randy Mastro |

1. Make the Mayor's Office of Emergency Management a permanent charter agency. |

all approved: Ballot Proposition #1 approved 70 to 30%; Ballot Proposition #2, passed 73 to 27%; Ballot Proposition #3 passed 55 to 45%; Ballot Proposition #4, passed 64.5 to 35.5%; Ballot Proposition #5, passed 67-33% |

|

Michael Bloomberg |

7/11/02 |

Robert McGuire |

Change mayoral succession. The public advocate would be interim mayor and a special election held within 60 days |

adopted 61-39% |

|

Bloomberg |

3/26/03 |

Frank Macchiarola |

1. Create a new system of "non-partisan" elections for all city officials. |

rejected 70-30% rejected 64-36% rejected 65-35% |

|

Bloomberg |

8/19/04 |

Esther Fuchs |

1. Establish ethics rules for administrative law judges and hearing officers |

adopted 79-21% adopted 71-29% |

* Commissions expire the day after their ballot proposal are accepted or rejected by the voters in the general election.

For an examination of the 2010 charter commission and its predescessors, see Bloomberg Moves to Change the Charter -- But How.

A Barrage of Bills

If we can learn one thing from the last session of the City Council, it's that introducing bills won't ensure you're re-elected.

Former Councilmember Alan Gerson, who lost his third term re-election bid to Margaret Chin last fall, was the first primary sponsor of more bills than any other council member in the last session. He introduced 84 pieces of legislation -- more than triple the average council member, according to council records. Only seven of his bills became law.

Gerson, whose legislative records are still packed in boxes and who is planning his first vacation in eight years, said his legislative history was "overstated" -- 10 of those proposals would have regulated street vendors, which he likened to a package rather than individual bills. Nonetheless, he does take some pride in his s-called achievement.

"We are a legislative body and the way to make a difference on a legislative body is problem solving through legislation," said Gerson.

But not every member took that approach. Council members Darlene Mealy of Brooklyn and Larry Seabrook of the Bronx were the first primary sponsors on just three bills in the last four years -- less than any other council member who served a full term between 2006 and 2009. Neither returned calls for comment.

There may be a lot that goes into being a member of the City Council, but one of its primary responsibilities is to propose, hear and enact legislation. According to an analysis by Gotham Gazette, some council members take that job far more seriously than others.

The Last Term

Under Council Speaker Christine Quinn's first term, 25 percent of all bills introduced became law -– a slight decrease from the number of bills approved under her predecessor, Gifford Miller. During his tenure, 31 percent of all bills were approved.

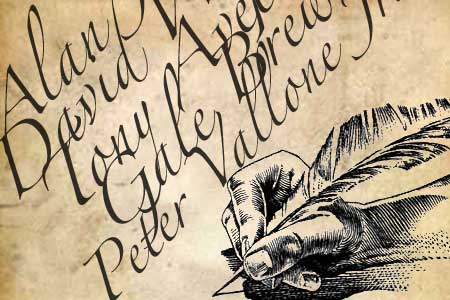

| Councilmember | Number of Bills Sponsored | Number of Bills Passed |

| Alan J. Gerson | 84 | 7 |

| David Weprin | 70 | 43 |

| Tony Avella | 64 | 2 |

| Gale Brewer | 63 | 6 |

| Peter Vallone Jr. | 55 | 10 |

To see the full breakdown, go here.

As defined by the City Council, a first primary sponsor is the member whose name is listed first on a bill when it is initially introduced. That legislator usually lobbies other members to sign on to the bill and often spearheads it through the legislative process. Council members do co-sponsor legislation with other officials and can introduce legislation together as a team. For those bills, our analysis counted only the first primary sponsor.

In the last session, which spans from January 2006 to January 2010, 1110 bills were introduced, according to the council. They range from the sensible to the outlandish -- from regulating the licensing of pedicabs to prohibiting peeping toms.

At times, members can be given credit for legislation that is pro forma, which has been assigned by the speaker's office to the committee they chair. For instance, former Councilmember David Weprin, who headed up the Finance Committee, was the primary sponsor of 70 bills in the last term. Many of them were standard finance-related actions, like the approval of business improvement districts, and some were submitted to the council at request of the mayor.

We have also not taken into account whether members accomplished their legislative goals through other means, such as through regulation or executive order. For instance, Gerson introduced legislation to change the way the Department of Transportation installed metal plates on streets -- an attempt to silence some of the cacophony created when a truck or car passes over them. His legislation was not approved, but Gerson said the changes were implemented through departmental policy.

And, officials said, the number of bills someone sponsors says nothing about the merit of those proposals.

"I do not believe the effectiveness of a legislator is measured by the quantity of the bills they have introduced, but rather by the quality of those bills and their impact on those they are meant to protect," said Councilmember Al Vann, who fell within the bottom of our analysis. He introduced six bills, including a proposal to designate high poverty areas as community development zones, a bill to require city-subsidized developers to prepare community impact reports and a proposal to give senior citizens protection from water bill liens. "I would be willing to put those bills up against any other three by another member as far as their importance to New Yorkers," he said.

Nonetheless, other officials argue there is a difference between some members authoring legislation in scores and others in single digits.

"Let me be kind and say perhaps they are focusing their efforts elsewhere," said Councilmember Peter Vallone Jr., who introduced 55 bills in the last session.

Swinging Away

Quinn by far has the best batting average for passing legislation. Of the 36 bills she sponsored, 78 percent became law -- the highest percentage of any council member. As speaker, Quinn sets the council's legislative agenda, and whatever she wants to move -- whether to a hearing or to the chamber floor -- will move.

On the other hand, some members, like Councilmember Charles Barron, claim the speaker's agenda setting can amount to political arm-twisting. If you don't make nice, your bill is like lead -- it sinks.

"When you're not in favor of the speaker your legislation will not be voted out of committee," said Barron.

Barron was the only member to not have any bill approved last session. He introduced 11 of them. On average council members got a quarter of their sponsored legislation approved.

Maria Alvarado, the speaker's spokesperson, said: "Every bill that is introduced goes through the same legislative process where it is fully reviewed and debated. Legislation moves forward by building a consensus and is passed based on its quality and merits. A bill's sponsoring member is not a factor."

At the beginning of her tenure as speaker, Quinn enacted several reforms aimed at giving individual council members more of a say over what happens to legislation. The move was seen as a break from the past, and was lauded by good government groups.

The reforms included a rule to allow members to bring legislation stalled in committee to the floor if the bill had more than seven sponsors. Quinn also installed a rule to allow members to propose amendments to legislation on the floor of the council.

Each of those rules has been triggered once in the last four years. An amendment was offered on the floor when the council considered term limits. It was defeated.

Councilmember Robert Jackson last December filed a "motion to discharge" to bring his proposal to require arbitration during commercial rent disputes to the floor. He later retracted the motion after fellow sponsors backed away from the bill.

Despite that defeat, Jackson said the legislative process is better under Quinn. "It's been much, much easier to move stuff if there is a disagreement… under Christine Quinn in comparison to four years earlier," he said.

Several measures that had the support of a majority of council members, such as a bill requiring paid sick leave, never came to the floor.

Last month, Citizens Union, the sister organization to Gotham Gazette's publisher, issued a report looking back at Quinn's proposals. While Citizens Union commended many of the council's reforms, it did suggest the council give individual members more freedom and independence to act on legislation. It should encourage members to offer amendments, the report states, without fear of political payback.