|

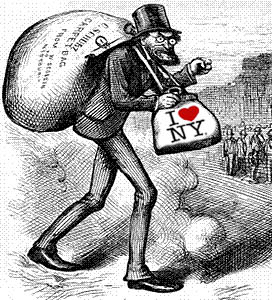

Carpetbagger |

As principal of Brooklyn Tech, one of the city’s largest and most prestigious public high schools, Lee McCaskill had been described as a “polarizing figure...ruling by intimidation.” But what eventually cost him his job was not that – but the fact that he lived in New Jersey.

Earlier this year, the Department of Education learned that, while McCaskill and his family lived in Piscataway, he sent his daughter to a highly regarded New York city public elementary school without paying, as the city requires of those who live outside the five boroughs. Under investigation, McCaskill resigned.

And McCaskill is not alone. In March, after McCaskill lost his job, at least 132 school employees told the Department of Education that they too lived outside the city, sent their kids to public schools and did not pay $5,500 a year tuition. But while some of those educators may gripe about having to pay to send their kids to free city schools, they can take solace in one thing: Unlike most other New York City employees, teachers can live wherever they want. Many city employees are required by law to live in the city itself and thousands more have to live in New York State.

It is apparent why the Department of Education sought to crack down on McCaskill and the other teachers. In essence, they cheated the city out of money as their children occupied seats -– usually in highly regarded schools -– that could go to bona fide New York City residents. But, in general, does it matter where a public employee or elected official lives?

NEW YORK’S POLICY: EXCEPTIONS RULE

|

Today, about 80 percent of all people who work for the New York City government live within the five boroughs, but this is far more than are legally required to do so. New York has a patchwork of laws and attitudes on residency requirements. While city residents voted overwhelmingly in 2000 for a senator who had lived and voted in Illinois and Arkansas, but never New York, the municipal government requires that a receptionist in the planning department live within the five boroughs. And while a teacher can reside wherever he or she pleases, a firefighter must have his or her home in one of 11 counties in New York State. Police Commissioner Ray Kelly must live in the city, but a beat cop does not have to.

The move for residency requirements gained force in New York City and much of the rest of the country in the 1970s. As middle class people fled to the suburbs, city officials struggled to keep as many salary-earning, stable people in the city as they could, and municipal employees fit that profile. Some officials argued that residency requirements would keep taxpayer money in the city rather than giving it to people who would use it to buy groceries and pay property taxes in New Rochelle. This argument still holds sway in poorer, more beleaguered cities, such as Buffalo and Detroit, but others question whether, in increasingly affluent New York City, the requirements have outlived their usefulness.

On a radio call-in program last August, Mayor Michael Bloomberg alluded to this. In the 1970s, he recalled, “there were forces to try to keep people in the city. Today we’ve got the reverse problem: Too many people trying to live here.”

The debate over residency requirements is as old as the country. "Every matter, and thing, that relates to the city ought to be transacted therein and the persons to whose care they are committed [should be] Residents," wrote George Washington in 1796.

And some residency laws date back centuries: In 1829, New York State enacted a law dictating that all firefighters live in New York. In New York City, the Lyons Law, passed in 1937, required city employees to live in the city. Under urging from Mayor Robert Wagner who called the law “inequitable,” the Board of Estimate repealed it in 1962.

By the 1970s, New York had a state law that said so-called public officers –- a vague term that includes people who have decision-making authority –- had to live in the jurisdiction that employed them. But the state expressly exempted from the law uniformed workers and those in independent agencies, such as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority or the Board of Education. (Teachers remain exempt even though the mayor has assumed control of the schools.) Over the years, the state has created some 70 exceptions to the rule, ranging from New York City sanitation workers to the dogcatcher of Onondaga County. As a result, city police and firefighters can live in the city, or in one of six surrounding New York State counties.

Mayor Ed Koch wanted all city workers –- even the exempt ones -– to live in the city, and the city passed a law doing just that. But the courts threw it out on the grounds that the city could not override the state law on uniformed employees. In response, in 1986, the city council passed a law that said any city employee hired after September 1 1986 and not exempted by the state laws had to live in the five boroughs. This law remains largely in effect.

DEBATING RESIDENCY REQUIREMENTS

In New York, the debate over residency requirements has involved activists on one side and employee unions on the other.

The Arguments For

Workers will be more available in emergencies: A commission appointed to investigate the violence that broke out during the 1977 New York City blackout cited a slow police response. It blamed this partly on the fact that, when the lights went out, many officers were at home in the suburbs, far from the streets of Bushwick and other hard hit neighborhoods. More recently, Bloomberg said that, if sanitation workers were allowed to live in the suburbs, it would be harder for them to respond promptly to emergencies, such as snowstorms. Ironically in New York City, many of the workers most vital to emergency response — such as police and prison guards – can live 90 miles away, while clerks and managers have to stay closer at hand.

City residents are more likely to understand and empathize with city residents: This argument is frequently raised with regard to the police department. “The hidden assumption, “the Times said in a 1986 editorial, “is that officers residing outside the city fall too easily into thinking of their patrols as â€occupation duty’ over an alien population.”

"If a person lives in the city, he can't help but have a greater feel for the city because he is here 24 hours a day," former Police Commissioner Lee Brown once said.

Following several fatal police shootings, as well as the police torture of Abner Louima, the Campaign to Stop Police Brutality, led by the New York Civil Liberties Union among other groups, called for a residency program “tied to an affirmative action plan for police officers to improve police/community relations” and increase the department’s effectiveness.

Following several fatal police shootings, as well as the police torture of Abner Louima, the Campaign to Stop Police Brutality, led by the New York Civil Liberties Union among other groups, called for a residency program “tied to an affirmative action plan for police officers to improve police/community relations” and increase the department’s effectiveness.

But others haved questioned whether it would make a difference. In 2001, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani said the city received fewer complaints against police officers who lived in the suburbs than against those who live in the city. “That doesn’t mean that police officers who live in the city are better or worse,” he said at the time.

But according to a 2001 poll (in pdf format) done by the City Council, 45 percent of city residents surveyed said requiring police officers to live in the city would be “very beneficial,” and 13 percent considered it “moderately beneficial.” Twenty-nine percent said it “would make no difference.”

Hiring city residents would create a workforce that, to paraphrase Bill Clinton, looks like New York: A study done in 1991 found that city residents applying for the police department were three times as likely to be Hispanic and four times as likely to be black as people applying from outside the city. If the city had to choose its employees from a pool of candidates where blacks and Latinos predominate, some argue, the workforce would reflect that.

Taxpayers’ money should stay in the city: People who work in the city do not live here do not have to pay city income tax or a commuter tax – it was eliminated in 1999.

The Arguments Against

People have a right to live where they want: This position sounds powerful, but the courts have not accepted it. In 2004, for example, the state’s highest court rejected the claims of a city maintenance worker who challenged the city’s residency law. And in 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the state courts and ruled against firefighters challenging the law that required them to live in New York State.

The courts seem to agree with a former mayor of Madison, Wisconsin, Paul Soglin who told Governing magazine, “People have a constitutional right to live anywhere they want. They do not have a constitutional right to public employment.”

The city is too expensive: Unions raised this objection when the city first moved to enact stricter residency requirements in the 1970s, and it has gained force today as middle class people find it increasingly hard to rent or own a home anywhere in the city, which represents many maintenance workers, clerks, technicians and other municipal employees who must live in the city, has said it is unfair that some of the lowest paid city workers are the ones who must live in the most expensive part of the metropolitan area.

Residency rules keep the city from getting the best employees: Hiring only people who live (or are willing to live) in the city narrows the pool of applicants from which the city can choose. When city school districts found it increasingly difficult to find qualified, certified teachers, many districts that had residency requirements for educators abandoned them. “With such a teacher shortage throughout the country, most districts are trying everything they can to attract teachers rather than create barriers,” a spokesperson for the American Federation of Teachers has said.

The rules are difficult to enforce: Some cities have resorted to spying. Buffalo has had a residency sleuth who conducted on site surveillance and interviews with neighborhoods to root out employees violating that city’s rules.

In New York City, some government agencies have asked some workers to sign affidavits and, in some cases, employees may blow the whistle on other employees. It seems likely the teacher’s union, which had been warring with Brooklyn Tech principal McCaskill, may have alerted education department officials that he lived in New Jersey.

THE EFFECT ON SPECIFIC PROFESSIONS

Whatever the merits of these arguments, residency requirements, and the debate about them, play out in different ways, depending upon the job.

Firefighters

Residency is a particularly sensitive issue in the fire department. Despite frequent vows by the city to diversify, the department remains 92 percent white and almost entirely male. And about half of all firefighters live outside the city. Some advocates argue that requiring firefighters to live in the city would bring more blacks and Latinos to its ranks.

Residency is a particularly sensitive issue in the fire department. Despite frequent vows by the city to diversify, the department remains 92 percent white and almost entirely male. And about half of all firefighters live outside the city. Some advocates argue that requiring firefighters to live in the city would bring more blacks and Latinos to its ranks.

For now, though, like police officers, firefighters must live in one of 11 New York counties: the five that make up the city along with Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester, Rockland, Putnam or Orange. Changing that would require action by the state legislature.

The department does give preference to city residents, adding five extra percentage points on to the department’s entrance exam. But according to Paul Washington, president of the Vulcan Society an organization of black firefighters, many people claim to live in the city when they do not. The additional five points “would have an impact if it was really enforced,” Washington says, but “it’s easy for candidates to get around it,” and the department “seems to find it impossible to come up with a residency criteria that really works.”

A 2001 audit by the city’s Equal Employment Practices Commission agrees that residency requirements might help bring people other than white men into the department. It cited an array of reasons for the department’s homogeneity, including a failure to verify residency claims. But the corrections department has the same residency requirements as the fire department, and has a uniformed force that is more than 80 percent black and Latino.

Sanitation Workers

Since 1986, city sanitation workers have had to live in the city. But late last year, the state legislature said that sanitation workers, like police and firefighters, could also reside in six other counties. The workers “are ecstatic,” Harry Nespoli, head of the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association, told the Daily News after Governor George Pataki signed the bill easing residency requirements. “They want a piece of the American pie. They want to own a home.”

Since 1986, city sanitation workers have had to live in the city. But late last year, the state legislature said that sanitation workers, like police and firefighters, could also reside in six other counties. The workers “are ecstatic,” Harry Nespoli, head of the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association, told the Daily News after Governor George Pataki signed the bill easing residency requirements. “They want a piece of the American pie. They want to own a home.”

Bloomberg, though, expressed irritation at the state’s intruding in what he saw as city business. “I don’t think any of these things should be up to the state legislature,” he said on the radio at the time. “It should be the city negotiating with its unions and the state should stay out of it -- whether it’s medical benefits, pension benefits, where you can live or any of those kinds of things.”

Elected Officials

Perhaps because so many New Yorkers come from somewhere else, voters here have accepted politicians from elsewhere. When New York was filling its first Senate seat in 1789, a Long Island native lost out to Rufus King of Massachusetts.

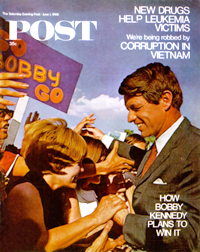

And in the years since, voters seem unfazed by politicians branded as Carpetbaggers, to use the term first coined to describe the Northerners who went South after the Civil War. Robert F. Kennedy became a New York senator even though he had spent most of his adult life in Massachusetts and Virginia. Hillary Clinton followed successfully in his footsteps more than 30 years later.

This year, people question whether William Weld was a carpetbagger when he ran for governor of Massachusetts, where he had lived for a number of year, or whether he is a carpetbagger now as he seeks to become governor of New York, where he grew up and has kept a summer home.

But some politicians have stumbled on the residency issues. Councilmember Bill deBlasio met with some derision earlier this year as he pondered whether to run for a congressional seat from Staten Island; the district includes a sliver of Brooklyn, but not the Park Slope area where deBlasio lives (and which he now represents in City Council).

But some politicians have stumbled on the residency issues. Councilmember Bill deBlasio met with some derision earlier this year as he pondered whether to run for a congressional seat from Staten Island; the district includes a sliver of Brooklyn, but not the Park Slope area where deBlasio lives (and which he now represents in City Council).

DeBlasio decided not to enter the race, but his City Council colleague David Yassky continues his quest to represent a congressional district, which his home is close to but not in. (To remedy the problem, Yassky recently moved.)

And residency requirements can offer an opportunity for the canny politician. Take Brooklyn Assemblymember Roger Green. In 2002, Green faced a vigorous challenge from lawyer Hakeem Jeffries. Green won but did not want to risk facing Jeffries again. So, when the state legislature set about redrawing assembly districts, Green made sure they moved the boundaries of his district by one block -- just enough to put the Jeffries home outside of it.

And now? Jeffries and his family have moved so they will be in the district. And Roger Green is running for Congress, to represent a district where he has lived for many years.

Â