|

|

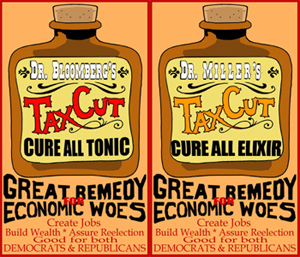

On a recent day at City Hall, Mayor Michael Bloomberg presented his annual $46 billion budget in the Blue Room on the west end of the building, while City Council Speaker Gifford Miller presented his budget in the Red Room at the east end of the building.

But when the two spoke about their rival tax cut plans, it seemed as if they had magically changed places.

The billionaire Republican Mayor Bloomberg sounded like a populist, accusing the City Council of catering to corporations and of neglecting the working people of the city.

"Somebody’s got to pay for the services," the mayor said, "and the truth of the matter is, the homeowners are less able than big business."

Meanwhile Democratic Speaker Miller sounded a lot like a Republican, arguing that a permanent, across-the-board tax cut for businesses and landlords would help stimulate the economy.

"They want a tax cut; they don’t want a check," said Miller. “They want to see their taxes go down.”

This year, New York’s budget battle has come down to tax cuts. Mayor Bloomberg wants to give $400 to each owner of a co-op, condo, and private house. Speaker Miller wants to reduce the property tax rate for all homeowners and businesses by two percent.

Despite their different approaches, the mayor and the speaker both start with the same basic assumptions about tax cuts:

- The tax cuts will reward those who helped the city weather tough fiscal times

- The tax cuts provide an incentive for residents to stay in New York

- They can help spur economic growth

And -- though not stated explicitly -- both officials clearly assume that the tax cuts will help get them elected in 2005.

However, many budget watchdogs argue that neither plan is particularly good for the city.

Can the city afford a tax cut? And do they really produce what politicians promise - or are they just a way to get votes?

THE RATIONALE FOR TAX CUTS

The theory of how taxes affect the economy, simply put is: If government taxes an item, it adds to the cost. As the price rises, fewer consumers wish to purchase the good and the quantity produced also decreases. The government gets the revenue from the tax, but both the consumer and the producer of the product bear the increased cost, and demand for the product will fall as a result.

The tax is not just a transfer of wealth from consumers and producers to the government; it is a permanent loss of economic activity to the whole society. This is why most economists agree that taxes reduce some of the incentive to spend, save, and invest.

At the same time, though, taxes pay for essential services that citizens demand from their government, such as schools, police officers, fire departments, and libraries.

While federal taxes have been instituted and rescinded in America since the mid-1800's, the notion of using tax cuts to "fix" the economy, experts say, is a modern one.

President John F. Kennedy issued one of the first major tax cuts designed to stimulate the economy, which was passed by his successor Lyndon Johnson in 1964.

Kennedy's plan instituted a new standard deduction, increased deductions for childcare expenses, and lowered taxes, including for those in the top tax bracket. The idea was that each dollar a person spent instead of paying taxes would go to another person who would spend it again. The plan used the immediate boost in economic activity to justify a government deficit. And the initiative is one that many economists point to as an example of successful tax relief. For a time, the national economy rebounded.

In local economies like New York's, tax cuts are often used to make a city more competitive with the surrounding area, and with other cities. New York City depends on an array of property, income, sales, and business taxes for revenue, and some argue that they affect people's decisions about where they work and live.

“There is some evidence that higher property taxes - all else being the same - are a factor in where people choose to live,” said Sanders Korenman, an economics professor at Baruch College.

However, one must also consider what those taxes are paying for. If taxes are cut, government spending must be cut as well.

"I don't mind paying my taxes because they fund valuable services like education," said Korenman. "You must look at taxes and expenditures together as a whole.”

Many people in the city point to the repeal of the commuter tax in 1999 as one of the worst tax cuts for New York City. State legislators in Albany eliminated the tax on people who worked in the city but lived in the suburbs as part of a political battle between the two parties over one upstate legislative contest.

The loss of the commuter tax costs the city $500 million a year in today's dollars - or enough money to pay for all of the city's parks along with all of its programs for senior citizens and for youth.

ARGUING THE PROS AND CONS

Once the discussion gets beyond basic economic theory, experts have wide and divergent views on whether tax cuts actually benefit New York City.

E.J. McMahon, a fellow of the Manhattan Institute, for example produced a study in 2001 concluding that 80,000 jobs - or one in every four new jobs in the city - had been created by local tax cuts in the previous five years.

“The lesson is clear: Tax cuts work,” wrote McMahon. “And in the years ahead, the best way to continue building New York’s job base will be to continue reducing its still-heavy tax burden – and by all means, avoiding adding to it.”

However, others, like James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute see the same Giuliani era tax cuts as mistakes that helped create huge deficits for the future.

“I can’t think of any [recent] local tax cut that has made sense,” said Parrott.

Parrott argues that the way for government to create jobs and make the city more attractive is to invest in education, housing, and new development projects. “In general, what the city can do to stimulate the economy," he says, "is most often on the spending side."

Most voters, however, want it both ways. They want their taxes to go down. And they want good schools, roads without potholes, and a police force to keep them safe.

"There is a core belief in the American political culture that government should be small, but we also want services," said Doug Muzzio, a political science professor at Baruch College. "The public wants a free lunch."

POLITICAL PARTIES AND TAX CUTS

Today, the Republican Party presents itself as advocates for smaller government and lower taxes, while the Democratic Party emphasizes vital services like education and social services for citizens.

But this was not always the case.

The first federal income tax was issued by a Republican administration, during the Civil War. For decades, it was the Democrats who painted the Republicans as a high taxing, big spending party.

It was not until the 1980’s that the Republican Party made tax cuts a fundamental part of the party’s ideology.

President Ronald Reagan argued then that tax cuts could not only stimulate the economy, they could also shrink government while creating greater wealth for the nation. Economists still debate whether the Reagan cuts really led to boom times, or just created huge deficits.

Today, tax cuts are once again the rule of Washington, where Republicans control the presidency and both houses of Congress. President George W. Bush has continued the tax-cutting legacy, issuing plans for $330 billion in tax cuts over the next decade. Even growing deficits and the Iraq war have not deterred officials.

“Nothing is more important in the face of war,” House Majority Leader Tom DeLay said last year, “than cutting taxes.”

The national trend has even had a profound effect on New York City, a town where Democrats outnumber Republicans five to one -- and where just six years ago, there was another apparent ideological switcheroo in a fight over a tax cut: In 1998, Miller's predecessor, Democratic Council Speaker Peter Vallone, Jr., called for the elimination of a 12.5 percent surcharge on the personal income tax, which cost the city roughly $500 million a year. Bloomberg's predecessor, Republican Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, said the city could not afford it. The reasoning behind the plan was no secret: Vallone's aides said that the speaker needed a tax cut to attract votes in his race for governor. The tax cut went through, but it did not translate into a win for Vallone.

“Since the late 1970’s and 1980’s, the political notion that tax cuts can help the economy has become more prevalent,” said Marcia Van Wagner of the Citizens Budget Commission, a group that has advocated reducing taxes in New York. “It’s become the political theme everywhere.”

THE MAYOR’S AND COUNCIL’S RIVAL PLANS

Both Mayor Bloomberg and City Council Speaker Miller argue that their tax cut proposals will help stimulate the economy and return some of New Yorkers’ well-earned money.

Mayor Bloomberg wants the city to write a $400 check to all homeowners who had to pay the 18.5 percent property tax increase imposed in 2002. Business owners and landlords of large buildings would not be eligible.

City Council Speaker Gifford Miller wants to roll back property taxes two percent across the board, including for commercial property owners. A single-family homeowner with a $400,000 house would get about $50, and the owner of a condo of the same value would get about $125. In addition, Miller would eliminate the entire 18.5 percent property tax increase for senior citizens on fixed incomes.

But under Speaker Miller’s plan, the mayor charged, the average homeowner in Queens would get just $49, while Con Edison would get an $8 million tax cut. Miller responded with charges of his own, calling Bloomberg's plan a "Bush-style gimmick."

The mayor’s plan would cost about $250 million a year and would have to be approved by the State Legislature in Albany. The speaker's plan would cost $297 million, and the council could enact it with a simple majority of its own members, or 26 votes.

However, many budget watchdogs argue that neither plan is particularly good for the city.

While the city government has a surplus this year, it is expected to have a $3.7 billion deficit in the fiscal year that begins in July of 2005. Even the mayor admitted that if the economy and tax revenues returned to their highest levels in history – which is unlikely – the city would still not be able to close the budget gap in future years if costs continue as expected.

More fiscally conservative groups like the Citizens Budget Commission say officials should use the money to pay down some of the city's debt. In a letter to the mayor, the group said that although it supports reducing taxes in the city, that his plan was a "mistake" that "distributes the money in a way that is largely ineffective in promoting economic competitiveness."

Left-leaning groups like City Project want the money spent on education and social programs. "Any tax cuts at this point in time - whether proposed by the mayor or the council - are premature and fiscally irresponsible,” said City Project's Bonnie Brower.

NOT ALL TAX CUTS ARE EQUAL

While the political rhetoric often oversimplifies the debate over whether taxes are good or bad, budget experts warn that the public must carefully consider various issues when evaluating any tax proposal.

“It very much matters which tax you cut or raise, and how you do it,” said George Sweeting of the Independent Budget Office.

Who Gets the Tax Cut?

One consideration is whether a tax affects all people equally.

In the case of the city’s property taxes, many agree that the elected officials would do better to reform the current system than to issue pre-election tax cuts. In 1993, Mayor David Dinkins did an assessment of the property taxes and found that the system was "inordinately complex” and “poorly understood by taxpayers." Commercial real estate owners, multiple apartment landlords, and utilities pay much more than single-family homeowners.

“I have friends who own brownstones in Park Slope who pay next to nothing in property taxes,” said Van Wagner.

Who Needs A Tax Cut?

Another issue is who is most able to afford a tax increase.

Last year, for example, the mayor and City Council imposed a surcharge on personal income taxes for residents who make more than $100,000 a year and couples who make more than $150,000 a year based in part on the argument that they are more able to afford it. However, it could be argued that the sales tax – which also rose in both the state and city to a total of 8.625 percent in 2003 – is tougher on lower-income people.

“With any tax cut one must ask if this is being done to improve efficiencies, or if one party wants to appear to give money to one group or another,” said Korenman.

Does It Make the City More Attractive?

Also, various taxes may have the ability to make the city more or less competitive with surrounding areas.

The city, for example, has lower property taxes for individual homeowners compared with those in the suburbs, but the city also has several business taxes that make it more costly for companies to have their offices in New York.

Can the City Afford It? The most important measure is if the government can really afford a tax cut. And that is when the arguments circle back to the beginning.

Some would argue that if the city government cut spending and lowered taxes, that the whole economy and government would fare better. Others argue that tax cuts will starve essential services, making the city dirtier, more dangerous, and in general a less desirable place, inducing people to leave.

“No economist will argue that taxes do not affect an economy,” said McMahon. “The argument is over how much it affects the economy, and how that is offset by other spending.”

Whether or not Mayor Bloomberg’s or Speaker Miller's tax cut is approved this year, some warn that the city’s situation is growing more tenuous. Budget experts on all sides agree that the city’s long term budget situation – with growing debt, increased costs for health care, and increased labor costs – is troubling.

And a recent report by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York concluded that the city’s tax revenues are less reliable than they were 30 years ago because they rely heavily on income and business taxes, which are less predictable than property taxes. As the city’s economy rises and falls, the report argues, so will the government’s finances.

As in the past, that means that today's tax cut may soon be replaced by tomorrow's tax hike.

Related Links:

Citizens Budget Commission

City Project

Independent Budget Office

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Fiscal Policy Institute

Manhattan Institute