In 2008, companies with a stake in natural gas drilling in New York spent a little less than $400,000 on lobbying. In 2009, that number tripled, with groups like the Independent Oil and Gas Association and Chesapeake Energy spending over $1,200,000. Lobbying dollars from the same sources only increased in 2010, hitting nearly $1,600,000.

What sparked that rise? Although most groups and companies spending that kind of money on lobbying have a myriad of issues before the state legislature, this spending spiked as the debate about the safety of hydraulic fracturing grew increasingly heated.

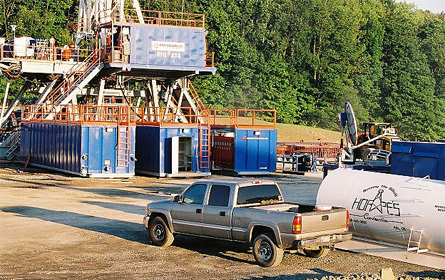

Hydraulic fracturing is the process by which natural gas is released from shale formations by injecting millions of gallons of water and chemicals into the earth. The natural gas industry says the process, along with the chemicals used, is safe, but there is concern that waste water from the process could contaminate local drinking supplies. The Environmental Protection Agency has discovered numerous pollutants in well water near fracking sites.

Common Cause, the good government group that conducted a recent study about the amount of lobbying dollars spent in the fight for and against what's known as hydrofracking, says that their study shows that those with more money are more likely to get heard.

"This is about big money and the influence it has on the debate. Those with the most money get heard," said Donna Bitetti of Common Cause. She says she is concerned about a recent deluge of television and radio advertising supporting hydrofracking, something groups like hers that oppose it or want to give environmental agencies more time to study the process simply cannot afford.

Looking for the Go-Ahead

Why have pro-fracking groups increased their spending? According to state Sen. Liz Krueger, an opponent of hydraulic fracturing who has introduced legislation that would steeply increase regulation of the process, the natural gas groups want the state legislature to quickly approve permits to allow fracking before scientific studies determine whether the process is safe or not.

Last year the legislature passed a moratorium on hydrofracking, a measure that was eventually vetoed by Gov. David Paterson. But Paterson then issued his own moratorium as an executive order to give the state Department of Environmental Conservation more time to study the process and the impact it may have on the environment. Meanwhile, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is doing its own study of the process. New York's moratorium expires on July 3. The state environment department is expected to unveil its study and new rules for hydraulic fracturing around then, and the public will have time to review and comment on the study before it becomes official.

It would be up to the DEC to allow permitting of hydrofracking in New York. The EPA conducted a study of hydrofracking in 2004 that found the process to be safe. Congress then passed legislation allowing states to regulate fracking individually. If the new EPA study finds fracking unsafe things could change.

But not all hydraulic fracturing that could affect New York's water supply is under exclusive control of New Yorkers.

In December 2010 the Delaware River Basin Commission, an interstate federal body led by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Parks Service and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, proposed regulations to oversee hydrofracking. It estimates that 15,000 to 18,000 wells could be dug in the Delaware River Basin, most of them for the purpose of hydrofracking. Its unclear how many of those wells could be in New York but the fear is that 50 percent of New York City's drinking water comes from the basin, and a well in another state could affect the city's water supply.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, who has steadfastly opposed hydrofracking, issued an ultimatum earlier this week. Either the federal government does a full review of the environmental impact of the commission's guidelines within 30 days or Schneiderman will sue.

"Both the law and common sense dictate that the federal government must fully assess the impact of its actions before opening the door to gas fracking in New York," said Schneiderman in a statement.

The Independent Oil and Natural Gas Association responded with this statement: "It appears to us that the commission is indeed working to do what it always has: to prevent water pollution in the Delaware River Basin. There is no reason to believe that the DRBC might somehow do other than what it always has done -- protect water quality and water supply and conserve the resources of the basin for the public’s recreation and enjoyment. ... The attorney general's statements today appear to run counter to New York's duty as a member of the DRBC."

Billion Dollar Battle

The stakes are enormous. Some fracking advocates estimate that New York could see $3.8 billion in revenues from hydrofracking in the Marcellus Shale and, using Pennsylvania as an example, $400 million in tax revenues. Meanwhile they say local landowners and localities would benefit from an infusion of cash from n the purchase or leasing of land and from the new industry the wells would bring in.

Fracking supporters say this money would be a boon to upstate's ailing economy and could also help shift some energy use from coal and foreign oil to domestic natural gas which produces less of the gases that cause global warming.

Opponents, though, point to what they see as a myriad of risks. They express particular concern that fracking could endanger New York City's water supply, requiring the construction of filtering systems that could cost billions and might not even be able to remove dangerous substances from the city's water.

Faced with such criticism, Kruger said, the industry seems to recognize it is "losing the high ground in the debate. They are spending money on lobbying and putting pressure on New York to try to approve this before the government says this is not a good idea. They are trying to get ahead of the science."

Krueger points to a recent New York Times series that focused on the dangers of fracking and spotlighted the damage it has done in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. The series unearthed federal government studies, allegedly buried by the Bush administration, that showed that fracking leads to pollution of well water. On top of that a recent study by Cornell University found that unearthing natural gas creates pollution as damaging to the environment as what's produced extracting coal.

James Smith, spokesman for gas association, denies that there is any rush. "The DEC has said they are not going to wait for the EPA. On July 1 we expect to have a new impact statement, and it will be open for comment a period. We hope it's short and everyone likes it. And then we hope they will start issuing permits," he said.

Smith also disagrees with Krueger that there has been a shift in the debate against fracking. "I think the debate has been pretty steady. There have been protests and rallies on both sides, op eds on both both sides."

The Court of Public Opinion

Smith says the industry may face a problem of perception. "It seems that the public has associated the word hydrofracking with pollution, and I think it got a bad rap," Smith said. "We still don't have any cases of ground water pollution due to hydrofracking -- that is not saying their haven't been issues elsewhere -- we just expect the regulations to be so tough in New York that it would minimize those type of events."

Krueger, however, says she thinks the message about the possible dangers of fracking is getting out despite the lobbying dollars spent to promote its alleged safety.

"Hydrofracking is the number one environmental issue. Not many people in New York live in western New York where the wells would be, but they have seen the pictures of Pennsylvania and watched the film Gasland. The New York Times has done a six-part series. So if you go up to someone in my district and say 'So, hydrofracking, huh?' they are very likely to say, 'Oh that is the thing that destroyed Pennsylvania and could pollute our water supply.'"

Bitetti of Common Cause isn't as confident. She has seen the lobbying dollars spent by the natural gas industry. She knows how much her group has spent in comparison to try to convince the public about what she believes are the dangers of fracking. And she has seen how the legislature has dealt with the issue.

She notes that the natural gas industry has been pouring money into PR and lobbying since way before the New York Times ran its series. Ads supporting fracking are commonplace on upstate television stations, and public radio. Thousands of fracking supporters -- residents of the areas that would stand to economically benefit -- have come to Albany en masse to lobby the legislature to allow them to use their land to make money.

Bitetti says she is encouraged that there are legislators like Krueger, "who introduced legislation that would basically ban fracking, but as soon as the legislation was introduced it was killed."

Krueger says she thinks the "grassroots" movement against fracking has taken off. She admits there isn't as much cash behind the push but she points to the anti-fracking lawn signs that cover some upstate neighborhoods, huge anti-fracking rallies in Albany and around the state, and the fact that fracking has become a hot environmental issue.

Tracking the Money

Common Cause and Bitetti now want to determine how much the natural gas industry has donated directly to politicians. That study, however, is difficult, as state campaign financing laws are not as strict as New York City's; individual donors don't have to name their employers. Along with that, it is hard to say that donations from the natural gas industry are aimed at promoting fracking, since the companies have other issues in front of the legislature, too.

Still, it is possible to get a basic idea of the kind of money that is pouring into politicians’ campaign chests. Gov. Andrew Cuomo received around $75,000 in donations from Competitive Power Ventures and its various subsidiaries. The company backs the use of natural gas and wind power -- two energies Cuomo supported in his energy position paper. Competitive Power Ventures has proposed building a natural gas plant in Wawayanda. N.Y.

Cuomo has received a number of smaller donations from companies interested in natural gas. He has raised the ire of advocates opposed to fracking by associating with members of the business community who have lobbied for fracking. He ationappointed one, Ken Addams, to be the CEO of the Empire State Development Corp. There is no clear connection between the coporation and the permitting of fracking, but anti-fracking advocates have taken it as a sign of who has Cuomo's ear. Adams as head of the Buisness Council strongly advocated to allow fracking.

The opponents just aren't sure where the most important decision makers stand.

Bitetti said she was encouraged when the new DEC commissioner said the new environmental impact statement would be released in the Summer and would allow for public comment. But her enthusiasm was tempered when nearly at the same time, "Norse Energy Corp. issued a random press release touting that they had had a great meeting with him just before he made the announcement."