New York's Creative Class

New York City is a world center for the creative arts: drama, music, dance, entertainment of every kind, art, photography, writing and publishing. Those hoping to be successful in these fields flock to New York City. These creative New Yorkers make the city distinctive in many ways - not just as a cauldron for innovation in the arts, and a magnet for tourism and conventions, but also as an engine of the economy: A new study for Lincoln Center found that the arts complex generated $1.52 billion in sales and employed 15,200 workers. Some argue that urban economic development and growth depend upon "The Creative Class."

Who are the individuals that make New York City the creative center that it is? Where do they come from, how are they faring? By analyzing census data we can get some answers.

How Many Are There? Where Do They Live?

Those who work in the creative and performing arts make up less than one percent of those who either worked or lived in the New York City metropolitan area, according to the 2000 Census. These included:

- 34,066 artists

- 28,682 writers and authors

- 22,860 musicians or singers

- 14,318 photographers

- 11,346 actors

- 3,684 dancers and choreographers

And 4,394 other entertainers.

Over a quarter of the people in these groups made their home in Manhattan, including 56 percent of all actors and 41 percent of all dancers.

This is sharp contrast to New Yorkers over all; only eight percent of people who either work or live in one of the five boroughs, reside in Manhattan.

Wherever they live, most creative professionals work in the city -- 73 percent of actors, 70 percent of dancers, 55 percent of artists -- most of these in Manhattan.

Who Are They Ethnically, Etc.?

A higher fraction of New York City's creative workers are white (e.g. actors 82 percent, artists 80 percent) than are other workers (51 percent).

Dancers are more likely to be female, but photographers and musicians are more likely male. A higher proportion than other New York City workers have never married. Members of the creative class are much better educated than other New York City workers, except for dancers; a much greater proportion finished at least four years of college. It is clear that many move from other parts of the United States to New York for their art. Fewer than average were born in New York State, but much more than average were "native-born", born in the United States, as opposed to abroad.

Struggling Or Thriving?

There are large differences among the various creative fields in terms of whether they worked at all "last week". About 28 percent of all actors did not work in the last week - the largest proportion out of work. Except for dancers, those in creative fields were more likely to have worked in the last year than other New York City workers.

However, the creative worker, except for artists and writers, earn less than the average New York worker; actors and dancers earned the least.

Considering how well educated the creative workers are they do not earn what their skills and background would command in more conventional fields. The average New York worker earned $29,000 in 1999. By contrast, one quarter of all actors earned $9,000 or less. Except for writers, the bottom quarter of each creative group earned less than did the bottom quarter of all New York City workers.

On the other hand, it really is possible to hit it big in New York in the arts. The top quarter of most creative groups earned as much or more than the top quarter of New York City workers as a whole. Some musicians and singers and artists reached the maximum reported income in New York in 1999, $627,000. (Of course, this represented just a small number, and it is not clear how accurate the numbers; the very wealthy among any group are well known to be much harder to reach and much less likely to give full information about their income.)

Generally, though, the creative in New York City, especially actors and actresses, earn less than the average New Yorkers, much less than New Yorkers of similar education and skill level. Some exist on very meager incomes and supplement their earnings from creative endeavors with that from waiting on tables, driving taxis, working in telemarketing and so on.

A few earn phenomenal amounts of money and live the celebrity dream, and a few more become quite successful and live comfortable upper middle class lives. But for the most part, if New York City's creative workers are a driving force for urban development, they are not the main beneficiaries.

The Citizen

|

The Citizen is in another location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

New York City Is a Non-Voting Town

Though it is common to call New York City a Democratic town, Democrats are actually in the minority. In election after election, the solid majority is made up of non-voters.

That is how roughly only 15 percent of all New Yorkers eligible to vote made Michael Bloomberg the mayor in 2001. In the last presidential election, in 2000, fewer than half of New Yorkers eligible to vote bothered to do so - and that is the highest it ever gets.

So who are these non-voters?

First of course are those who are not eligible to vote. Of the six million New Yorkers who are 18 years of age and older, only about 4.7 million are citizens. Breaking that down ethnically, there were:

• 12 percent of non-Hispanic whites not eligible to vote

• 20 percent of non-Hispanic blacks not eligible to vote

• 34 percent of Hispanics not eligible to vote

• 54 percent of Asian not eligible to vote

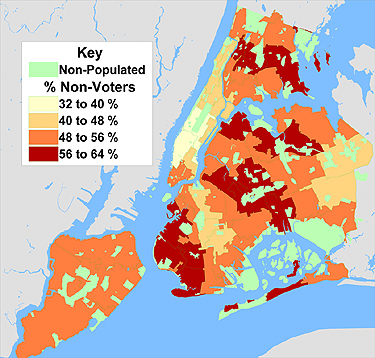

As the accompanying map shows, the areas with the smallest proportion of non-voters are in Manhattan, including the Upper East Side, the upper west side and areas south of 59th Street.

The highest proportion of non-voters live in

- Bensonhurst, Borough Park, and Bay Ridge in Brooklyn

- East Tremont and Bronxdale in the Bronx

- Astoria, Flushing and East Elmhurst in Queens, along with Middle Village, Howard Beach, and Ozone Park.

In short, there is no direct relationship between economic distress of an area and non-voting among those eligible.

Every two years after every national election, the United States Census Bureau asksa representative sample of the US population if they voted. Using those data for the period after the 2000 Presidential election one can get a picture of those who do not vote even for President. (Of course asking someone whether or not he or she voted is likely to elicit a certain amount of lying. Indeed, about 55 percent of those sampled claim they did vote, about seven percent more than those who actually did.)

- Women are more likely to vote than men (57 percent to 52 percent).

- Blacks are more likely to vote than whites (61 to 57 percent).

- Renters are slightly more likely to be voters than owners (57 to 54 percent).

- Those that own a business are more likely than those who do not (62 to 55 percent).

- Those working and those retired are more likely to vote than those without jobs (60 to 50 percent). However, there is no relationship between family income and voting.

Those in higher status occupations and those with college degrees voted at a higher proportion than others eligible (68 to 55 percent).

Those married with spouse present, as well as those widowed, divorced or separated voted at much higher rates than singles or those living without their spouse. Those born in the United States were slightly more likely to vote, while those from Puerto Rico were slightly less likely to vote.

Though some demographic and other groups do vote at a somewhat higher rate than others, it is nonetheless the case that for virtually every population category non-voting is rampant. This is all the more true in non-Presidential contests, even when a handful of votes would make a difference.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

The Citizen

|

The Citizen is in another location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

New York's Divided Afghans

Â

As a recent court case makes clear, the Afghanis who fled to New York City do not seem to have entirely escaped the turmoil back in Afghanistan, one of the poorest countries in the world, and one that has been wracked with both internal divisions and external invasions for most of the last 25 years.

Shortly after September 11th, 2001, Imam Mohammed Sherzad, the spiritual leader of the Hazrat-I-Abubakr Sadiq Afghan Mosque in Flushing, accused the founders of the mosque of supporting the Taliban, and in effect kicked them off the premises. The founders accused the imam of making up his accusations in order to take control of the mosque. They sued. Last month, a state supreme court justice reportedlyreturned the mosque to their control.

The case offered a glimpse into a community that seems nearly as divided here as in Afghanistan. And, thanks to the U.S. Census Bureau, which for the first time released data on 89 so-called ancestry or ethnic groups from the 2000 census, we can begin to piece together a demographic portrait of this complicated community as well.

The census found about 9,119 individuals of Afghan ancestry who live in the New York metropolitan area, a figure far smaller than the 20,000 normally cited. Of course, the census bureau may have missed some Afghans (as many as 30 percent), but it also likely that the higher figure is an exaggeration.

About two-thirds of the Afghanis were foreign born. Most left their homeland because it was no longer safe. Of these, more than half fled the Soviet invasion starting in 1979. Others fled when the Taliban militia took over in 1996. Still others fled during or after our bombing of Afghanistan in 2001 and 2002. These three groups may well have very different views.

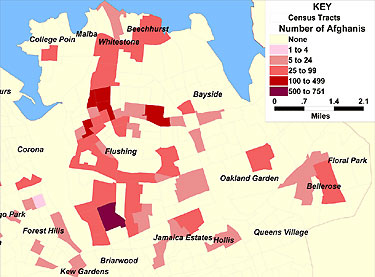

The Afghanis in the city are relatively poor, with a median household income in 2000 of about $25,000, compared to about $38,000 for all New Yorkers, and about $50,000 for Afghanis in Long Island. Afghans are highly concentrated residentially in and around Queens, especially Flushing, as shown by the accompanying map.

Afghanis are more likely to be male, to live in a family, and to have had no schooling than New Yorkers as a whole. The 55 percent of Afghani New Yorkers who are male are much better off than the women. About eight percent of the men and almost 25 percent of the women have never attended school. Indeed, over 70 percent of Afghan men between 21 and 64 were employed in 2000 according to the Census, which is almost identical to the 69 percent rate overall for men in New York City. But only 26 percent of Afghan women were employed, which is well below the 58 percent rate for all New York women.

Manizha Naderi, the director of Women for Afghan Womenreports that before some Afghani women are allowed to go to the ESL class sponsored by her organization, their husbands check it out to make sure that the class is not being run by a communist or Catholic organization. The organization also helped to sponsor a conference in Kandahar to write a Bill of Rights for Afghan Women that was supposed to have been made part of the new Afghan constitution. Despite many promises, it was never added. Many Afghanis in the New York City would agree that Afghan women should not have a Bill of Rights.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Ikea And Red Hook's Racial Divide

"I have to laugh at the groups who say Ikea is splitting the neighborhood," says Judith T. Dailey, a long-time resident of Red Hook in Brooklyn. "The fact is Red Hook has always been split."

Dailey was among scores of Red Hook residents who attended a recent meeting of Community Board Six in Brooklyn to support the proposed building of a 350,000 square foot Ikea superstore on the Red Hook waterfront. . The boardis expected to give the necessary approvals for the project to go ahead.

Environmental groups have joined with some Red Hook residents to oppose the project. They point to the proliferation of big box stores on the city's waterfront, as well as the increase in traffic and air pollution.

The longstanding divide that Judith Dailey alludes to is between residents of Red Hook Houses, a public housing project where about 70 percent of the neighborhood population lives, and homeowners in "The Back." But this division is more than just about turf. The majority of people in Red Hook Houses are people of color, and the most vocal residents of "The Back" seem to be white. Only the public ethic of color blindness allows everyone to politely forget the mention of race as a factor in this division.

Ikea's opponents correctly point out that the trucks and over 9,000 cars per day that Ikea will attract will create havoc in this peninsula that functions well as an urban village. The planned reconstruction of the Gowanus Expressway, or its deconstruction and replacement with a tunnel, will route even more traffic through Red Hook for over a decade. Ikea is proposing to re-engineer several intersections and widen some streets, but that will only make it easier for people to drive to Red Hook, whether for Ikea, the new Fairway planned for another waterfront site, or any number of other new commercial giants waiting in the wings to gobble up Red Hooks vacant waterfront sites.

But according to Judith Dailey, "The traffic won't kill us, we need this window of opportunity." Representatives of tenants at Red Hook Houses believe the 500 to 600 jobs promised by Ikea are more important. Perhaps 60 percent of those jobs will be full-time and Ikea has promised to accept applications from Red Hook residents before opening up the hiring process to others. They also propose to provide training.

Ikea Looking Good

On the surface, Ikea looks pretty good when compared to the standard head-strong developer who plows ahead without consulting with their future neighbors. This Swedish multinational giant with 180 stores in 31 countries looks like a socially responsible neighbor when compared to bull-headed predators like Wal-Mart and Home Depot, or the despots of downtown Brooklyn, Forest City Ratner. Instead of ignoring public housing tenants as developers, Ikea talked with them. And tipping their hats to the other side of the Hook, they put in a few environmental innovations, like a small green roof. They committed to keeping a barge operator - one of the last vestiges of the working waterfront - as a neighbor, and say they'll start a ferry service and shuttle to the nearest subway. In all, despite charges that it exploits labor and contributes to the destruction of forest land in poor countries, Ikea has a pretty good public image.

But before giving any civic awards to Ikea, consider what they're NOT doing. First of all, there's nothing in writing to guarantee local jobs. Verbal commitments alone can easily evaporate, and the recent history of big box stores raises serious questions about the quality and long-term viability of their jobs (see the recent articleby Hilary Russ in Gotham Gazette). Ikea's goal of 100 prtvrny local hires is hardly altruistic. Most of the jobs pay modest wages that won't attract workers from long distances anyway.

Secondly, the street improvements Ikea says they will pay for are more likely to help the SUV drivers coming to shop from all over the region than Red Hook residents. Ikea isn't helping to create safe pedestrian or bicycle ways in Red Hook and instead will bring more traffic through the most heavily populated areas, including public housing. Ikea needs to make the street improvements to get past the legally-mandated environmental review and they would lose time and money if they had to wait for the city to make the changes.

Third, the ferry and shuttle bus seem to be only icing on Ikea's cake, since the company estimates that 85 percent of its shoppers are going to drive there anyway.

Fourth, by providing public access to the waterfront, Ikea is not giving anything extra to Red Hook. It would be required to do this under the city's commercial waterfront zoning.

Lost Opportunities

Precisely because Ikea is more open and willing to give something back to the neighborhood that welcomes it, we have to ask why they're allowed to get away with giving so little. Wal-mart and other big box developers are eyeing Red Hook, so doing the right thing with Ikea could set a higher standard for future proposals. If Ikea could genuinely integrate their project into a revitalized Red Hook it may not turn out to be yet another corporate enclave on the waterfront.

There are at least three reasons why Ikea is a lost opportunity.

The first reason is that it leaves intact the historic divide among Red Hook residents (and businesses, too). This fits neatly with the classic role that racism has played in community development: it allows developers to divide and conquer. Until our color-blind officialdom starts talking honestly about race, it will continue to undermine the ability of communities to have a say in planning their futures.

Secondly, city agencies that should be playing a proactive role are, at best, passive players. Why isn't the Department of Transportation and the Department of City Planning telling Ikea to reduce the amount of parking, beef up public transit, or find a better location? The Department of Transportation years ago rejected the de-mapping of truck routes in Red Hook that run through residential streets, so I guess it would be out of character to now be concerned that pedestrians might get run over by Ikea's trucks and shoppers.

Finally, the Ikea proposal ignores the official plan for Red Hook, which was approved by the City Planning Commission and City Council. This plan was developed a decade ago in a two-year-long process that brought together the neighborhood's diverse residents and businesses. It projected a vision of a mixed industrial/residential community without separate waterfront enclaves. The city takes no responsibility for implementing this plan. After it was approved the Red Hook plan was put on the shelf and forgotten. If the city's planners took it seriously they would remind everyone that the Ikea site was to be preserved for industrial and maritime uses. This policy is consistent with the city's own Waterfront Revitalization Plan. So why isn't the city sending Ikea and the parade of other big box stores to downtown locations where subways and buses are already in place, and promoting industrial and maritime uses on this section of the waterfront?

Perhaps the divisions in Red Hook give city officials a good excuse for their actions and inactions. Both Ikea and the city could use their considerable power and resources to bring everyone to the table. But perhaps that's too much to ask for. When people start working together they may envision a future that goes far above the bottom line and remember their own visions for the future of their neighborhood.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

Flaws In The New School Tests

High-stakes testing of schoolchildren has been causing high anxiety not just among students and their parents, but also for teachers, principals, superintendents, even public officials - all of whose fates, in a very real way, are now determined in part by these tests. Some of the latest headlines warned that, thanks to the mayor's new policy to end "social promotion," the results of the tests for third graders in New York City public schools indicated that some 10,000 of them may be forced to repeat third grade next year. As more provisions of the No Child Left Behind Acttake effect, more and more such testing will occur. Is it any wonder that the press has started to publish charts that track these scores in every single school?

But what do these tests actually measure? The truth is something that those who produce the data from the tests admit only privately: The entire process is seriously flawed. Even sustained increases over time may tell us much less about the academic performance of a student or a school than about the testing itself.

Educational researchers know that there are better ways to assess the progress of both individual students and entire school systems than the process now mandated by New York.

The current testing process is fundamentally flawed in at least three ways.

UNRELIABLE TEST RESULTS

Fundamental to the use of these tests is the assumption that they measure the same set of skills and knowledge from year to year, and for the same sort of students. But in fact a score from one year may not be equivalent to the same score the following year. It is impossible to know whether a change in a test score from one year to the next is due to a change in actual student performance or to an unintended change in the make-up of the test. Obviously, one cannot use the same questions from year to year, and even though much effort goes into making sure that the test given in 2004 yields the same standards as the test form in 2003, it is a difficult task to be absolutely sure this is so.

TEACHING TO THE TEST

No one who is working in any of the hard pressed urban schools in New York State can doubt the advantages of getting higher test scores on the English and Language Arts (ELA) and mathematics test. If a school does not improve, it may find itself on one of the several "bad school" lists prepared by the State Education Department. The school may be reconfigured; and the principal may lose his or her job or be reassigned.

So, once the new test was established in 1999, it is not surprising that districts and schools realigned their curriculum. However, as with any standardized test, there are specific things about the test itself that one needs to learn to do well on it. James Traub's article "The Test Mess," in the April 7, 2002 New York Times Magazine follows the efforts (or lack of efforts) of three districts to prepare for the exam. Such test prep can work, but it costs time, effort and resources for drill and practice. Now with the No Child Left Behind Act, there are complaints that schools are sacrificing additional parts of the curriculum to prepare the students for the test material only.

Companies now market test prep approaches to school districts. State grants, in part based upon federal money are now available for supplementary educational services that include test preparation. No matter how effective such programs are, they certainly must displace time and resources that could be used for other classroom activities, so improved scores may come at the expense of other learning.

PLAYING GAMES WITH TEST SCORES

Some commentators noted that Mayor Michael Bloomberg's efforts to end social promotion starting with third graders should lead immediately to an improvement in fourth grade test results next year, since many of the low-performing students will no longer be slated to take the test. Such "gaming" of high stakes test standards is rampant throughout the US. (See my August Columnon counting dropouts)

A host of such approaches are being used to make the results look better, from suggesting the poor-achieving students stay home, to reclassifying them as special education or English As A Second Language students. One year New York City suppressed the test results for seventh grade, when they indicated a drop, after trumpeting them the year before when they indicated an increase. New York City is not alone. A national studyfound evidence of just this sort of Enron-style accounting among school systems throughout the United States.

BETTER METHODS OF ASSESSMENT AND TRACKING

To assess educational progress at the state or large city level, the United States Department of Education developed the National Assessment of Educational Process. It is a test based upon knowledge determined to be needed at various grade levels. This is not a high stakes test, since it is only given to a sample of students, and the results are used to track overall educational performance change and have no consequences for a specific school or student.

One does not learn anything about the effect of schools on individual students from the current testing regime, nor would one from a test like the National Assessment of Education Process. An alternative approach that overcomes many of these difficulties is the so-called "value added" approach. One tracks the gains for each particular student, not the raw test score averages for each school, district, county or state.

In this way one can relate the student gains to specific schools, teachers and educational practices. This testing approach was mandated as a remedy to civil rights violations in a Tennessee court case and is being used in some other states as well. The value added method goes well beyond simply grading schools on whether the percent of students who passed a state-mandated exam increased or decreased from one year to next. Rather it takes into account where the student starts and the extent to which growth occurs while the student is enrolled in a specific school.

New York State and New York City it seems, rely upon an inferior and invalid method of tracking student progress even though they use the information it provides for many decisions affecting schools and students. Perhaps, given the brouhaha over the recent release of test scores, more realistic methods of tracking and assessment will be adopted - especially if parents and educators demand them.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

The Citizen

|

The Citizen is in another location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

The Citizen

|

The Citizen is in another location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

Estimating New York City's Population

Earlier this month, the United States Census Bureau declared New York City to have the highest population ever, based on a new estimate. According to the bureau's newly-released annual county population estimates, New York City's population now stands at 8,085,742. The estimate of population growth since the 2000 Census is as follows:

38,000 from 2000 to 2001

17,000 from 2001 to 2002

14,000 from 2002 to 2003

In other words, according to the bureau, the city's population is still growing, though its rate of growth has substantially slowed since September 11th.

All of this was duly reported in the press. However, some demographers disagree with the bureau's method of estimating population.

Warren Brown of Cornell University says that the count is much too low. Currently he is helping New York City launch an informal challenge to the estimate. For example, the census bureau is saying that Brooklyn lost population from 2002 to 2003. But city officials point outthat the borough has gained some 4,000 housing units since the 2000 census 2000. Surely, they say, this is concrete evidence that the borough's population is on the rise.

But other demographers, myself included, believe that the new estimate for the city's population may instead be too high. I think it likely that New York City has actually been losing population since September 11th.

CENSUS ESTIMATES REQUIRED BY LAW

Federal law requires the census bureau to make estimates of the nation's population in-between the official census, which, as required by the U.S. Constitution, is conducted every ten years. These estimates are used for many purposes, including: allocating over $200 billion in federal funds; calculating such statistics as birth, death and crime rates determining the location of public and private services; computing controls for federal surveys;

To estimate the population the census bureau uses the "components of population change" method, which takes the number of births, subtracts the number of deaths and adds or subtracts the net number of people who migrated into or out of New York City. This number is then added to last year's population estimate.

If any of these figures are wrong the estimate will be wrong. Births and deaths, of course, are relatively simple numbers to acquire, since they are recorded throughout the United States. But gauging migration is much trickier. The bureau uses two estimates -- one for net domestic migration and another for net international migration. The Internal Revenue Service produces a file that reports the number of people who change the county in which they file tax returns from one year to the next. This file is considered quite reliable except for its ability to track college students, military personnel and others who may move unpredictably.

Getting truly accurate estimates is challenging, especially in places such as New York City.

TRYING TO CORRECT PAST INACCURACIES

During the 1990s, as I have discussed in earlier columns, the census estimate of the growth in New York City was too low by about 50,000 per year. It became obvious that the way the bureau estimated the growth of the foreign born population was grossly inaccurate. Since the bureau used the number of individuals who received permanent resident status by county in a given year, they missed people who entered or stayed in the United States illegally, those on student and work visas, or those who are visiting the United States for other reasons.

So beginning with the 2002 estimates, the census bureau began to use the new American Community Survey(ACS) to estimate changes to the foreign born population. This survey will replace the census long form, which asked about 50 questions of roughly one-sixth of the population in 2000. It will be a large continuous collection of social and economic data and will offer a continuously updated picture of every locale in the United States, down to each census tract (which in New York City can be a single block). But this survey is not yet implemented in every county in the United States, because it is yet to be fully funded. For this reason, the bureau cannot determine if the number of new foreign born at the national level has changed significantly since the 2003 data are not yet available.

Furthermore, they are not yet confident in using information at the county level from this data set. To estimate change in foreign born in each county, they assumed that the pattern found in the 2000 Census continued through 2003. Therefore, this method does not take into account changes in the number and destination of new foreign born caused by a reaction to 9/11 or the worsening New York City economy. According to Signe Wetrogan, the assistant division chief of the bureau's Population Estimates and Projections of the Population Division, bureau officials are reviewing methods and data, so that they can create leading indicators of population change, such as employment figures and yearly school enrollment.

THE EFFECTS OF CHANGING MIGRATION OF FOREIGN BORN

All these technical details mean that the estimated net number of new foreign born coming to New York City each year since 2000 is about 104,300. If Warren Brown is right, and the foreign born or other migration estimate is too low, then the city's rapid 1990s growth may indeed be continuing. It is certainly possible that the Census's new method has missed many new foreign born.

However, I think it is more likely that just as net out-migration to the rest of the United States increased after 9/11, the number of new foreigners coming to New York City would have decreased, as well. If the number of new foreign born actually declined by 17,000 or more after 9/11, then New York City has lost population in the last two years.

Until the census bureau refines its methods we cannot be sure if New York City's population is growing, declining or stable. However, I think it is important to be patient with the bureau and its efforts to get this right. When it has more confidence in its data and methods, it will simply re-estimate the population change in New York City, not just for one additional year, but for all of the years back to 2000.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

The Citizen

Â

|

The Citizen is in another location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |