We Deserve The Right To Be Forgotten

(photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

An old school newspaper editor once told me through a cloud of cigar smoke, “The accusation? That's front page news. The acquittal? You're lucky if that makes the paper at all.”

Being “innocent until proven guilty” is one of the most sacred tenets of the American criminal justice system. But in the modern digital age, “innocence” is something the acquitted or the wrongfully accused never fully achieve, because, on the internet, their name stays forever affiliated with the crime for which they were charged. That’s why we should be pushing to institute a national “Right to Be Forgotten.”

Imagine you are accused of a crime you did not commit. After what was most likely a long and traumatic trial, the judge or the jury finds you did not commit the crime, and you are released from the custody of the state. All you want to do is get back to normal life. You apply for jobs (you lost yours during the trial), but, mysteriously, you keep getting turned down, despite a clean record. The fact is, you may have successfully cleared your record, but you will never clear your name, because every trace of media where you are referred to as the suspect, the accused, or the alleged perpetrator remains online forever.

Every single article, video, tweet, Facebook post, and any other media remnant easily pulled up on the internet, will still be the top hit on a search engine, despite your innocence before the court. It’s an injustice that has no place in our system, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

A “Right to be Forgotten” law would require search engines like Google to remove any links to articles and publications that associate a person with a crime for which they’ve been found not guilty. The content is not destroyed – there would be no loss to the work of journalists who covered the initial charge – but by removing widely accessible links that pop up in simple searches, the law attempts to make it significantly more difficult for the average person on Google to discover a person’s affiliation with an accusation that was determined to be unfounded or untrue.

Right now, we attempt to “clear” a person's name by publishing an article of their acquittal, and consider the record corrected. But we all know this is not how modern media works. Depending on the situation, your charge and your mugshot gets thousands upon thousands of views, whereas your acquittal (months or years later) maybe gets a few hundred. There is no amount of record-correcting that can overpower a person’s affiliation with an accusation. Once we see a person’s name connected with a crime, even if we know they’ve been acquitted, it’s the accusation that sticks. Innocence be damned.

Now, there are certainly some people, and some crimes, to which this should not apply. Public figures (like elected officials or heads of major companies), should not receive this protection, in order to preserve the public’s access to information that may be in their interest. In addition, crimes like sexual assault, which have an abnormally low conviction rate and are often comparatively difficult to “prove” in the eyes of the court, could also be exempt. But there is simply no good reason that the average person accused and acquitted of a crime should carry the burden of guilt for the rest of their lives.

Don’t get it twisted, I’m all for the free flow of information, and preserving the public record as best as we can. But we have to recognize that the modern digital age presents a unique problem, where the ruling in the court of public opinion matters almost as much – if not more in some cases – as the one in criminal court.

For this legislation to have an impact, it would have to be passed on a federal level, with the power required to regulate large search engines and internet providers. I cannot push this legislation on the city level, but I urge my colleagues in Congress to take up this cause, and help preserve the innocence of so many. The old newspaper editor was right: the accusation is almost always front page news but you're lucky if the acquittal makes the paper at all. We need to uphold the power of innocence, or innocence itself ultimately loses its value.

***

City Council Member Justin Brannan represents parts of Brooklyn. On Twitter @JustinBrannan.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Changing Brooklyn Politics One Block at a Time

(photo: @newkingsdems)

After the 2016 election, I was one of the millions of people who felt helpless and depressed about the state of politics. To feel less helpless and depressed, I decided to get involved; the only problem was that I had no idea where to start. Sure, I marched, donated, and even hosted a few letter-writing parties, but I couldn’t shake a nagging feeling that, somehow, it wasn’t enough.

Then I got an email from #RepYourBlock, a campaign led by the New Kings Democrats, asking me if I wanted to run for a seat on County Committee – the official governing body of the Democratic Party in Brooklyn. And I know this sounds cliché, but after receiving that email everything changed.

But before everything changed, I was the new person at my first meeting, watching a bunch of confident, passionate, and super impressive strangers use a whole bunch of lingo I didn’t understand to talk about a complex issue I knew nothing about. It was scary. It was intimidating. And it was humbling.

But I was determined to make an impact. I was going to do more. And so I stuck with it. I went to another meeting. I learned more about the issues affecting my community. I introduced myself to some of those intimidating strangers from that first #RepYourBlock meeting and quickly learned they were sweet, caring people who were more than happy to help me get up to speed and explain things again when I didn’t get it the first time. (That happened often, and still does.)

Running for County Committee starts with petitioning to get on the ballot. In my case I had to collect about 35 signatures of registered Democrats who lived in my Election District — it seems easy but can still be very intimidating when you’re doing something like this for the first time. That's why it was so great to have the company and moral support of my County Committee partner, a lovely gentleman named William who has lived in the building around the corner from me for the past 15 years.

I met William briefly at a #RepYourBlock petition training event just a month before petitioning began, he gave me his business card and a couple of weeks later I called him to ask if he wanted to be partners, hoping he remembered me from the meeting a couple of weeks prior. He did, or at least said he did, and together we hit the streets! #RepYourBlock printed our petitions, and provided us with a walk-list of registered Democrats so we knew which doors to knock on.

I now have two years as a County Committee member under my belt. I can’t tell you how empowering it feels to be a part of a community of people who roll up their sleeves, get involved, and band together across Brooklyn to fight to make the Brooklyn Democratic Party more transparent, participatory, and representative.

#RepYourBlock was founded to help fill the thousands of vacant County Committee seats - with the idea that by increasing participation, we could improve the Brooklyn Democratic Party's capacity to represent and work for Brooklyn Democrats. It exists to make sure that these seats are open to anyone who wants to get more involved in local politics, not just close allies of elected officials. County Committee members help dictate party business and are even sometimes afforded the power to fill legislative and judicial vacancies, and we think all kinds of everyday Brooklynites should have a say.

And although we’ve made a lot of strides with #RepYourBlock, we still have a long way to go. Because in truth, County Committee has been historically run by a complacent party machine. I'm hopeful that the party's newly-elected "boss", Assemblymember Rodneyse Bichotte, will bring positive change.

Too often, the party machine (with its hold on County Committee) has been content to make many decisions -- such as about which races to prioritize and candidates to support, how to spend the party’s money, and who gets to become a judge -- behind closed doors and keep us out of what should be a truly democratic process. But I know first-hand that if we can inspire our neighbors to run for these seats, we can change the way politics works in Brooklyn. We can make sure our neighborhoods are represented and our voices are heard.

But how much can you really do on County Committee?’ Well, someone once said to me, “If it’s not working on the local level, it’s not going to work on the national level,” and that’s exactly why getting involved with #RepYourBlock to run for the most local of local party positions -- a seat on County Committee -- is so important. You’re actively participating in a process that leads to tangible progress. As a member of County Committee you have the opportunity to connect with neighbors who are passionate about increasing political engagement in your Assembly District and beyond.

In an effort to have the greatest impact in this role, I and other County Committee members from Assembly District 50 formed an Assembly District Committee, or ADC, a creation of the party rules through which we regularly hold voter registration drives, candidate forums and other outreach events.

Join County Committee and you have officially “gotten involved.”

If you’re feeling similar to how I did after 2016, then I invite you to get involved for our 2020 push.

We’re building up the grassroots infrastructure in the party, activating more Brooklyn voters, encouraging electoral competition in Brooklyn, and increasing transparency in the judicial nominating process – and we need people like you to make it happen. So be brave. Challenge yourself to do more. And step just a little bit outside your comfort zone. Because I promise you, it’s worth it.

Petitioning to get yourself on the ballot can happen in a weekend, and it takes place this February and March. If you’re a Brooklyn Democrat, sign up to learn more now at the #RepYourBlock website.

***

Michele Kaufman is represents the 19th Election District in Assembly District 50, and is Secretary of the Assembly District Committee.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Time for Public Power for New York

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

New York’s Public Service Commission recently approved another rate hike for Con Edison, as it does every three years. This hike will increase electric rates by 13% and gas rates by 22% over the next three years.

Con Edison won. Like always, it requested and was granted its rate hike. It doesn't matter that New Yorkers already pay the second highest municipal rates in the country. Nor the $200 million for new fossil-fuel infrastructure baked into Con Ed's request. Despite this, state regulators are once again allowing them to increase rates and their return on investment. The regulators ignored that Con Edison has been absolutely disastrous for New Yorkers.

Last year, hundreds of thousands experienced blackouts, brownouts, and shutoffs. Some of these happened on the hottest days of the year. And they mostly happened because Con Ed hasn't done routine grid maintenance. But when you are an unaccountable monopoly, profits to your shareholders will always win out over safety and health.

The reason Con Ed is so profitable is simple, we allow them to be. It cannot fail financially because it is a privately-owned monopoly providing an essential service: energy. For this, state regulators don't care if projects complement or harm New York's goals of reducing our carbon footprint. To regulators, there is no difference between a solar farm or a new fracked gas pipeline. For Con Ed, new fracked gas pipelines are easier and cheaper to connect to the existing grid, so with their contractually guaranteed return, they choose and advocate for a gas pipeline over a microgrid every time. In this rate case Con Ed did just that!

And don't get us started on the coercive actions of National Grid, whose self-imposed gas moratorium hurt thousands of New Yorkers. This phony crisis was all an attempt to bully New York into approving another dirty fracked natural gas pipeline. Luckily, National Grid lost, but it is still asking for a rate increase of over 17% this year.

The science tells us that we have a decade to shift from a fossil-fuel based economy to one of renewables. That won't happen with Con Ed or National Grid. Only one PSC Commissioner, Tracey Edwards, had the courage to break the insane cycle of ever- increasing rate hikes coming at the expense of the environment. In voting against this increase she said, "I can't support it because I want to just push us [the state] further and further to go faster and faster [toward renewable energy].” She's right. Con Ed and National Grid have proven that they will not get us there. They have proven that profits and shareholders come before our environment and ratepayers.

That is why there is only one thing for New York to do: make our utilities and electric generation publicly owned, 100% renewable, and democratically controlled.

First, New York should invest in the necessary energy generation to make all state-owned properties 100% renewable by 2025.

Second, turbocharge renewable energy production by allowing the New York Power Authority to own renewable energy production. With our current for-profit model, New York generates only 5% of our energy from wind and solar. To meet the state's codified climate goals, and to face environmental realities we need to do much better. Direct investment and ownership of renewable energy production is the only way to make a meaningful change.

Finally, consolidate the privately-owned downstate utilities into the Downstate Power Authority, a democratically-controlled and publicly-owned utility.

This publicly-owned distribution utility will provide rates cheaper than what we pay now, while having democratic oversight. With this, we will finally have a distribution utility run for and by the rate-payers.

If we do these three things we will transform our energy system into one that recognizes the scale of the environmental crisis we face. We know our current utilities have no interest in being part of this transition. That is why we have introduced three bills that will give power to the people by bringing Public Power to New York.

***

Robert Carroll represents the 44th Assembly District in the New York State Assembly. Aaron Eisenberg is a climate activist with the NYC Democratic Socialists of America. On Twitter @Bobby4Brooklyn & @ae53 of @nycdsa_climate.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Is the MTA’s Plan to Redesign the Queens Bus System an Improvement?

(photo: Patrick Cashin/Metropolitan Transportation Authority)

Is the MTA’s plan to redesign the Queens bus network an improvement, or will it further destroy the bus system?

The MTA released its Draft Queens Bus Network Redesign on December 30. Queens voices have protested the plan from Woodside to Bayside and Whitestone, from Jackson Heights to the Rockaways. There also has been concern from Maspeth, Glendale, and Middle Village, from the bus drivers’ union, and reaction from Rep. Tom Suozzi.

Assemblymember Brian Barnwell from Maspeth wrote a letter to then-MTA New York City Transit President Andy Byford, strongly objecting to the plan to eliminate bus routes and asking for discussions to take place in additional neighborhoods such as Astoria and Elmhurst. Legislators also met for one hour with Byford in Albany to express concern.

Any massive changes will meet with some opposition but why all this resistance from so many neighborhoods? It is because all these neighborhoods will lose service so that other neighborhoods can be better served. That is unnecessary. It also is unavoidable when you are insisting the changes be cost-neutral without making strategic investments. Congestion pricing funds, set to start rolling in early next year, will be allocated only for capital improvements.

Cost neutrality also means that some worthwhile ideas will most likely be removed to pay for service additions requested by communities. That way, the MTA can claim the public participation process worked. Bus ridership will only increase if you provide more service, not less.

Why does the MTA propose to cut service provided by the MTA Bus Company, such as discontinuing Sunday express bus service, when these services are fully subsidized by the city? One theory that has been floated is that the city is exerting pressure on the MTA to reduce their bus subsidies so the funds can be freed up to provide additional ferry service, which requires even greater subsidies.

Before the release of the Queens draft bus report, I previously discussed why the MTA is not correctly performing these borough redesign studies.

The MTA repeatedly stated that these are only draft proposals. The question is whether the MTA is willing to go back to the drawing board to make major modifications, or will only make a few minor adjustments where the outcry is the greatest and then declare that the public participation process worked.

Several years ago, the MTA proposed to eliminate bus service on Newport Avenue in the Rockaways. The proposal was withdrawn after protests by Community Board 14, but is being proposed again. How can Byford’s claim that the effort is “customer driven” be true when the MTA is blatantly ignoring communities’ wishes?

Over 300,000 people a day depend on Queens buses. Only about 3 percent of them are aware of the Queens Bus Network Redesign. Each workshop, the primary form of publicity, attracts a few dozen participants because they are ineffectively publicized. The final plan will be presented to the full Community Boards only for informational purposes. Requests for presentations to Community Boards will be made to the Transportation Committee of about ten people, not the full boards where the public attends. The vast majority of bus riders will only learn of the changes a few days before they take effect, or as the routes change.

On the new MTA website, you must click under “System Modernization” to learn about the redesign studies rather than a more obvious designation like “Bus Network Redesign Studies.” The other alternative is to search for “Queens Bus Network Redesign” or go to the exact webpage for information. That assumes you already know about the study before you search. You will not learn about the study or the workshops If you search “Planned Service Changes” or “Public Notices” from the MTA.

The workshop format is also under attack because unlike town halls requested by elected officials, it doesn’t allow reactions to be shared in an open forum for all to hear, and it doesn’t create a record of the plan’s deficiencies so that suggestions for changes can be evaluated. Oral comments can easily be overlooked. It epitomizes the premise that service planners know best and the citizenry does not understand what is best for them. Workshop means no consensus among participants so the MTA can still carry out its intended plan. The required public hearings come far too late in the process for meaningful changes to be made and are mere legal formalities.

The plan also features new zone express services in Southeastern Queens, some new routes, some routes that are discontinued or shortened, as well as the elimination of many bus stops, which the MTA disguises as “bus stop balancing.” In effect, most local routes will become Limiteds. It does not serve the public to have a local bus route stopping every five blocks and an SBS on the same street. This will be a hardship for anyone who has difficulty walking. Some streets have buses stopping over a mile apart, such as the QT5 on 101st Ave. There is an on-line petition opposing removing so many bus stops.

The MTA’s primary goal is to reduce operating costs. Many one-bus trips become two- and three-bus trips which does not accommodate the greater good. In Eastern Queens, in some cases, two buses will be required to access the subway instead of one, or a long walk of three-quarters of a mile. This will be especially inconvenient in bad weather and is certain to discourage ridership, necessitating further service cuts. Direct north-south service is desirable, but direct subway access needs to be maintained during peak hours.

There are many opportunities for the MTA to become more efficient, such as through better scheduling where buses do not travel halfway across the borough while not in service, and the merging of NYCT Bus and MTA Bus Company depots. Saving money should not be at the expense of the passengers.

Bus speeds can be increased with a state law requiring non-emergency traffic to yield the right of way to buses pulling out of bus stops, not by eliminating most bus stops or spending $6 million a mile on unnecessary exclusive bus lanes as proposed that will further increase traffic congestion without significantly helping bus riders.

The MTA will never admit failure. Ridership losses will be attributed to the next fare increase. The MTA will insist the losses would have been greater if the network were not redesigned. The lack of predetermined criteria to measure success or failure is a chief shortcoming. Faster bus speeds are to be expected when you space bus stops every quarter or half mile apart, rather than every two or three city blocks, forcing some riders to walk a half mile or more to a bus stop when the traditional planning standard is a maximum of a quarter mile walk to a local bus. This is in no way an indication of success. The major criterium should be “can more trips be made in less time from origin to destination?”

The MTA promised a 30 percent quicker commute with the Woodhaven SBS. It only delivered a three-minute savings for trips greater than three miles, but still declared success. Now it is proposing to eliminate the Q53 SBS by curtailing service to Woodside and Jackson Heights where the ridership is very heavy, ignoring the data, discontinuing a route it called a success, and turning a one-bus trip into a three-bus trip. How can the MTA be trusted to provide a system that better meets the needs of the passengers? The public must vehemently voice their objections to prevent all negative outcomes.

***

Allan Rosen is former Director of Bus Planning, MTA NYC Transit. On Twitter @BrooklynBus.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Minding the Medicaid Gap

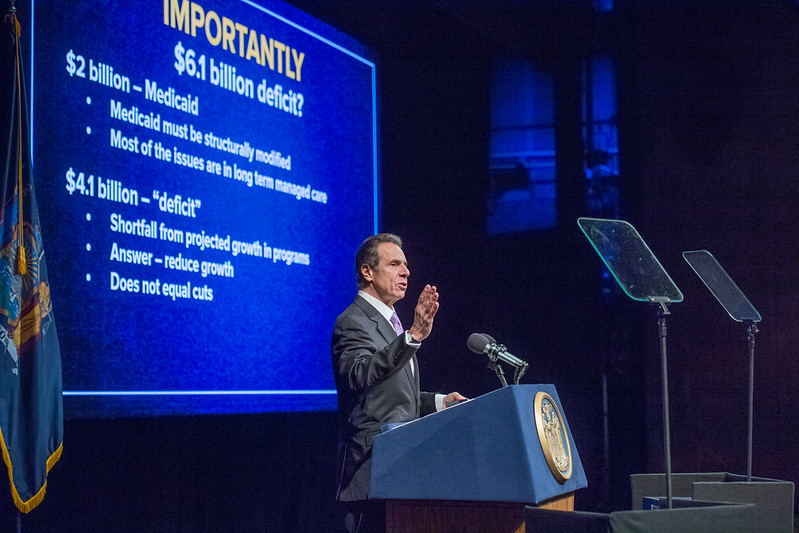

(photo: Darren McGee/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo)

Albany chatter in anticipation of Governor Andrew Cuomo’s 2020 State of the State message was dominated by the prospect of a $6.1 billion budget gap. How to fill it? Tax? Cut programs? All unpalatable.

Of course, budget gaps are nothing new. In an opinion essay published in the Rochester Beacon just three days before the governor spoke, his Budget Director Robert Mujica pointed out that annual “baseline gaps” are routinely closed by controlling spending growth. “Last year,” Mujica wrote, “the baseline gap we closed was $5.3 billion; in recent years it has ranged from $3 billion to $4 billion.”

Three things were new this year though: the gap’s size, its source in a massive area of the budget previously thought to be under control, and its potential for future rapid growth if left unaddressed.

When he finally got to the subject, well into his more than hour-long message, Governor Cuomo attributed the budget gap “largely to our Medicaid cost.” Medicaid in New York will cost $73.8 billion in the current (2020) fiscal year, combining federal and state monies, because Cuomo said, of “federal cuts and…cost increases incurred when local governments were held harmless by the state for Medicaid increases.”

The governor did not mention that New York State remains unique in the nation in the degree to which it required its 57 counties and New York City to help pay Medicaid costs from local source revenues. According to a 2017 National Association of Counties report, “Counties contribute to Medicaid in 26 states. Of these, 18 mandate counties to contribute to the non-federal share of Medicaid costs.” But no state’s counties pay more than New York’s, “$7 billion per year – or $140 million per week.”

Nor did Cuomo mention that the property tax cap, which constrains counties’ ability to meet the costs of their Medicaid share, was enacted at his initiative.

Nor did he mention that this year’s budget gap was widened by rolling forward a far greater amount than usual in state Medicaid spending - $1.7 billion - from the 2019 to the 2020 fiscal year, in order to stay under another cap, the Medicaid Global Spending Cap, created in 2011 by the state to keep these costs in check.

In Cuomo’s first term, and in part of the second, per enrollee Medicaid costs were cut, and then held in check even as the covered population grew by over 1 million people – a stellar achievement by the governor’s Medicaid redesign team. But cost growth resumed in 2017 and thereafter, and absent decisive intervention, is projected to continue growing at an unsustainable pace.

The Budget Division’s mid-year update to the state’s 2020 financial plan attributed Medicaid spending increases to two policy choices: the aforementioned state assumption in the growth of the local Medicaid share and the phased-in increase in the state minimum wage to $15 per hour in some parts of the state, enacted in 2016.

“The FY 2019 State Operating Funds spending increases include over $900 million for the incremental cost of the local Medicaid growth takeover,” the Budget Division wrote, “and nearly $800 million for the direct cost of the minimum wage increase to health care providers,” which is passed along to the state and the localities. While the first was highlighted by the governor in his speech, the second, a key achievement highlighted during the 2018 campaign for governor, went unmentioned.

Medicaid is administered in New York State through the counties and the City of New York. In the governor’s view, now that these localities have less skin in the game, an unintended consequence is that they have less incentive to seek efficiencies. “You cannot separate administration from accountability,” Cuomo said in the State of the State. “It is too easy to write the check when you don't sign it.”

Of course, even with some of the financial pressure relieved, the counties and New York City are still left with a big aggregate obligation; for 2019 it totaled $7.2 billion. Moreover, a major element of Medicaid reform, authorized by law in 2012, has been to “transfer responsibility for the administration of the Medicaid program from Local Departments of Social Services to the [state] Department of Health.” Significant progress in achieving this goal, and plans for future steps, were documented by the state Health Department in a report to the governor and Legislature in December 2018.

Following up in his January 21 budget message this week, Governor Cuomo revealed how he proposes to link writing the check with paying it. The state would continue to cover the increase in local share it had assumed, but only if New York City and the counties stayed annually within the 2 percent property tax cap and limited their yearly growth in Medicaid costs to 3 percent. If they go over this annual growth rate, they would pay the difference. If they went under, they would share the savings. (Cuomo is also empaneling another Medicaid redesign team, tasked with finding $2.5 billion in savings.)

All this assumed, of course, that actual control of the level of spending for Medicaid is in local hands. Even though more and more of the administration of Medicaid, as a matter of state policy, is in the state government’s hands. Even though demand for services might rise because of changing social or economic conditions, entirely outside of local control.

There is another way to cut the Gordian Knot. It is precisely to incentivize efficiency and accountability that reformers have long advocated full state government assumption of responsibility for the Medicaid program. For example, the Citizens Budget Commission wrote in a 2018 report: “It is time for New York to adopt measures that will completely eliminate the required local share of Medicaid.” This very good idea would achieve precisely what the governor is advocating.

Where would the money come from? In many jurisdictions increased sales tax authority was authorized for localities to pay for Medicaid. With no Medicaid obligation to meet, New York City and the counties could be required to relinquish some of this resource.

Thus a big tradeoff: counties would be relieved from responsibility for administering Medicaid and paying any share of the program’s costs. In return, the state would reclaim that portion of local sales tax revenues required to cover localities’ former Medicaid share.

This would fully make one government, the state government, both the “check writer” and the “check signer” for all of Medicaid. And the governor would then have the full control he needs to achieve the economies he thinks possible but unachievable under the current shared responsibility for the program.

***

Gerald Benjamin is director of The Benjamin Center at SUNY New Paltz. On Twitter @TheBenCen.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Surveillance and the City: Cuomo's Camera-On-Every-Corner Boondoggle

(photo: Governor's Office)

Even a terrible product can sometimes do some good. That’s the case for automated license plate readers (ALPRs), the disturbingly prolific tracking tool that have propagated across the country. When Grafton Thomas allegedly attacked a Hanukkah gathering in Monsey last December, ALPRs helped police identify him. It was a high-profile win for the increasingly-controversial technology, which has come to track nearly every vehicle in New York City.

Governor Cuomo responded to the news with $680,000 for the town of Ramapo, which contains Monsey, and the nearby Village of New Square to install ALPRs. But his support went even further than that. ALPRs even made an appearance in the governor’s State of the State policy book. There, the governor urged the Legislature to both expand the state’s ALPR system, which was set up starting in 2016, and to begin the process of updating existing ALPRs with more sensitive cameras.

There are no details on where the new cameras might go or how high the tab might run, but costs could easily go into the hundreds of millions of dollars. The problem is that while the surveillance-minded governor is quick to highlight the nightmarish scenarios where ALPRs could be useful, he doesn’t say one word about privacy.

ALPRs are not just invasive, they may soon be unconstitutional. That’s the concern raised by the Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling in Carpenter v. United States, where the high court ruled that it was unconstitutional to track an individual for a prolonged period without a warrant. In Carpenter, the technology was different, but the privacy implications were exactly the same. There, police used cellphone tower data instead of ALPRs to create the digital tracking device.

It’s jaw-dropping to think that the State of New York might invest a small fortune in an arsenal of cameras that it could have to shutter in just a few months. That’s because the type of ALPR system the governor is endorsing only works by tracking each and every one of us. It’s not a targeted search for one person on the run, it’s a constant log of where every car goes. In short – it’s a China-style surveillance state.

If the governor required every driver in New York State to wear a GPS ankle monitor before they were let on the road, it would help in the occasional criminal investigation, but we would recognize that the privacy price is too high. ALPRs may not be as physically painful as an ankle monitor, but the civil rights objections are the same.

But while the risks in ALPRs are clear, the benefits are ambiguous. Governor Cuomo promised that ALPRs would be a “deterrent for future attackers,” but it’s hard to see how. In the horrific attack in Monsey, a man in mental health crisis took aim at the Jewish community. He wasn’t a rational person who would weigh the levels of surveillance before striking out, he was an unhinged individual whose mental illness caused him to commit horrific crimes.

We all want to feel safe. We all want to believe that those in positions of power have the tools to prevent “the next one.” And so well-intentioned politicians feel tremendous pressure to do something, anything to show that they are taking the threat seriously, to show that they are responding. But the truth is that no police technology or surveillance device will be able to predict and prevent anti-Semitism. And we should all know that by now.

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, we were told that we needed draconian prison sentences. We didn’t. In the ‘90s and 2000s, we were told that we needed broken windows policing and stop-and-frisk. We didn’t. Now, we are told that we need omnipresent surveillance and that it’s the only way to prevent hate crimes. It’s not. It’s clear that we don’t need this wasteful surveillance spending. What’s unclear is if anyone can stop it.

***

Albert Fox Cahn is the founder and executive director of The Surveillance Technology Oversight Project (S.T.O.P.) at the Urban Justice Center, a New York-based civil rights and privacy group and a fellow at the Engelberg Center for Innovation Law & Policy at N.Y.U. School of Law. He writes the monthly "Surveillance and the City" column for Gotham Gazette. On Twitter @FoxCahn & @STOPspyingNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Following Our Faith, Marshaling Our Resources to Solve Homelessness in New York City

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

It was early evening on a street corner on the Upper West Side. A young woman rushed up to me and asked for money so she could buy some dinner. She was flushed, out of breath, and pregnant. Stories like this are a frequent occurrence for any New Yorker who walks the streets and takes the subways.

This young woman said she’d had a fight with her boyfriend and he’d kicked her out of their apartment. She had just been placed in a shelter and didn’t have supplies or food. Despite my desire, knowledge and connections, I couldn’t solve the complexities in her life that had brought us together. All I could do in that moment was give her enough money to buy a decent meal in the neighborhood. I did, and walked on, deeply troubled both by her situation and by my inability to make a real difference.

As New Yorkers, we have an obligation to do something to help our neighbors who experience homelessness. The question is, how can we make a difference?

Many people on the streets suffer from mental illness and substance use disorders and have histories of criminal justice involvement. Many had childhoods filled with domestic violence, child abuse, family instability, overcrowding, inadequate nutrition, inconsistent education, and poverty. The effects of structural racism make these problems even worse for people of color. Whether or not we give money to people asking for it, we must acknowledge the essential humanity of the person in front of us and support ways to make our society more compassionate, and effectively so.

It’s important to understand how homelessness has become so widespread, despite the dramatic increases in spending that have occurred under successive city administrations. It must be baffling that despite these increases, there seem to be so many people on the streets asking for help.

Some context matters. The number of single adults in shelters has increased by 65 percent in just the past six years. Sadly, this should be no surprise. The number of psychiatric hospital beds in the city has been significantly reduced from 2014 through 2018, and we are laudably moving to reduce incarceration rates (including the closing of Rikers Island, where 40 percent of the inmates have severe mental illness). The shelter system was never intended to be the housing solution for people suffering from serious mental illness – but where else, other than the streets, can they go?

In order to truly make a difference for New Yorkers who are homeless, we should concentrate our energy to make the city’s large shelter and support system fully realize its potential to help homeless people achieve maximum independence. This is in keeping with Jewish teaching, which urges us to ensure that poor people have what they lack in order to attain self-sufficiency.

We need to stop thinking of shelter as a band-aid or emergency. Shelters should be purpose-built with in-house services the clients need most. They should be small enough to be manageable, especially for clients that are severely challenged; and they should be operated by reputable nonprofit providers like mine, that are open 24/7/365, delivering social services, medical care for both physical and mental health, good nutrition, job training, and support to find permanent housing, all with good governance and oversight.

Shelters like these should also be in every community—including yours! Many people are afraid of shelter and supportive housing opening in their neighborhoods. The prophet Isaiah urged that we should take the poor into our homes; this teaching was deemed so central that it is read every year on Yom Kippur. In our day, we can enact this mandate by committing to be vibrant communities that care for all members.

You can become involved by getting to know the nonprofits that operate in your community, and the people that run them. You can participate in Community Advisory Boards that meet regularly with nonprofit operators. You can volunteer, join a board of directors, and if you don’t feel comfortable giving handouts on the street, commit to providing ongoing financial support to the nonprofits that provide services.

I invite you to join me on Sunday, January 26, for Reconstructing Judaism’s New York Day of Learning: Jewish Response to Homelessness in the New York Area. We’ll discuss how Jewish texts and values can guide both individual response and public policy, and explore how we can accomplish systematic change.

I often think of that pregnant woman I’d met and hope that she and her child are now in better circumstances. What I know is that if we invest in shelters and affordable housing, and consider them communal responsibilities just like local hospitals and schools, we can make that crucial difference for people like her. No, we won’t eliminate homelessness, but we can help each and every person who is homeless find the right path forward for them. As we read in Pirkei Avot, a collection of rabbinic wisdom dating to the third century, “You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.”

***

Eric Rosenbaum is President and CEO of Project Renewal, a leading New York City homeless services agency, and is also a board member of Reconstructing Judaism, the central organization of the Reconstructionist Movement. On Twitter @reconjudaism.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Social Value of Bail Reform

Assemblymember Blake, one of the authors, at a recent rally

On January 1, as New York took a considerable step towards a more just and equitable criminal justice system, we heard the all-too-predictable objections to bail reform. Now, along with the chorus that tried to shout down reforms in the last legislative session, we hear some of those who supported these reforms wanting to undo a policy that takes seriously the rights of low-income New Yorkers and communities of color—because of a tragic incident in Monsey that has nothing to do with bail or reform.

As a black state legislator who represents Latino, African, African-American, and white residents in a Bronx district whose citizens have long borne the brunt of inequitable and unjust bail policies, and as a Jewish nonprofit leader whose organization is headquartered in the same district and has worked in jails and prisons for decades, we are appalled that the bitter pain of racism and a resurgence of anti-Semitism are being used to divide us rather than bring us together.

Let’s look at the facts. The purpose of money bail is to ensure that defendants—people who are only accused of a crime and thus are legally presumed innocent—will appear in court. It is not meant to be a punishment or a fee. Yet for many people, it represents an insurmountable financial barrier to release that carries dire and life-altering consequences. We have many examples of individuals like Kalief Browder and thousands of others who were arrested and held not because they were a flight risk, but simply because they or their families could not afford bail. Kalief experienced such violence and torture while detained that he took his own life after release. Layleen Polanco never made it home and died while detained on $500 bail.

We cannot ignore the historic and systemic racism, sexism, and ageism at the root of many criminal justice policies, nor can we pretend that bail does not criminalize poverty and perpetuate injustice, and we must recognize that pretrial detention actually diminishes public safety.

Detention is more likely to cause crime than improve public safety. A report from the Arnold Foundation revealed that people detained for two or three days were almost 40 percent more likely to commit a crime before trial than those detained for less than 24 hours, and those held for more than a month were 74 percent more likely to be arrested for a new crime.

How could this be? After just a few days of detention, people may lose their jobs, miss rent payments, or have their children taken away. After a month, these consequences become even more pronounced and threaten community ties that are crucial to stability and wellbeing. To make matters worse, people who are detained awaiting trial are far more likely to accept plea agreements, even when innocent, because they want to go home — see the exonerated Central Park Five — or be convicted of a crime than similar defendants who are not subjected to conditions that damage their wellbeing.

Contrary to the rhetoric of many critics, our reformed bail law does not encourage prosecutors or judges to let “dangerous people walk free.” New York has never permitted preventive detention based on a prediction of future “dangerousness.” Prosecutors and judges have long worked within a system that asked them to consider only whether a person was likely to return to court and provides many options to support people in returning to court that do not depend on financial capacity.

The truth is that most of the benefits of cash bail went to private insurance companies in the bail bond business, and that we are terrible at predicting future behavior. We should not allow the present fear-mongering to create more punitive and harmful bail and detention policies than those we reformed during the last legislative session in Albany.

We stand together for bail reform and all policies that address the underlying inequities and biases in our legal system. It is time to give bail reform a fair chance and not allow this thoughtfully-constructed law to be undone under the pretense of fighting anti-Semitism.

Yes, there is more to do. We must continue to implement programs that increase public safety while addressing inequity. New York City has been working to ensure that people who are released from court or jail are offered needed social services, an approach that should be supported by those who claim to be so concerned about releasing people who were previously being held for ransom they could not pay.

We look forward to a productive and progressive 2020 legislative session that builds on last session’s reforms and continues to shift New York towards a more just and equitable legal system.

***

Assemblymember Michael Blake represents the 79th District in the Bronx. Elizabeth Gaynes is President and CEO of The Osborne Association. On Twitter @MrMikeBlake & @OsborneNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Manufacturing is Alive and Well in New York City, But It Looks A Lot Different Than It Used To

(photo via the Mayor's Office)

As the spring semester begins for New York’s high school and undergraduate students, many will soon shift their focus from studies to a career. Generations ago, the options were pretty straightforward for students without an advanced degree: build something or sell something. Today, the job market is quite different.

The information age has opened up all kinds of new opportunities for young people. At the same time, the traditional industrial or manufacturing job has changed as a result. Those who “build something” spend as much time typing up code as pounding out widgets.

Indeed, manufacturing has not left New York—it’s evolved and grown. Largely gone are the massive factory floors and smoke stacks. In their place, we now have clean rooms and miles of fiber optic cable. Are things still made in New York? Yes, lots of things. How they are made, however, looks more like the Jetsons than the Flintstones.

But education and training have not caught up to the new manufacturing age in New York, and now there is a skills – and, frankly, perception – gap when it comes to attracting new workers to growing industries that desperately need to fill well-paying jobs. These jobs include interesting careers in green manufacturing, marrying tech with manufacturing, and local projects related to smart city upgrades.

So how do we close the gap? Through education and training programs, and by actively engaging young people about the opportunities available to them in New York’s modern manufacturing sector.

For instance, here is how companies like ours – Quadlogic and Lee Spring – have adapted and are working to address these challenges.

Lee Spring has been manufacturing metal springs, wire forms and stampings in New York for more than a century. How Lee Spring makes its products has changed remarkably, however. Lee Spring used to physically make each part step-by-step, requiring a labor-intensive multi-step process using multiple machines.

Today, the company has developed automated systems that make the entire part in one step, are calibrated and controlled by technology-enabled factory teams, and monitored by a management team working away from the factory floor. This technology has allowed us to grow internationally, with facilities in six different countries, all overseen by our management team at computers in Brooklyn.

Quadlogic is a relatively new company, making smart meters for municipalities, including New York City. But Quadlogic doesn’t just build the meters here—it has developed a team of information workers who also help cities optimize use of the meters through the Internet of Things. Quadlogic is both a manufacturer and an information company.

And the efficiencies that technology created also allows for relatively modest energy use. There are no smoke stacks at our facilities. They have been replaced by highly-tuned quality-control systems that minimize our carbon footprint.

That’s what manufacturing in 2019 looks like in New York. And we have entry-level jobs available that can easily approach six-figures, even without a four-year college degree and the debt that comes with it. The average manufacturing and industrial sector wage in New York is $65,000. Yet we struggle to find applicants, nevermind good candidates—even though no manufacturing background is typically needed, and most training is on-the-job. Digital skills are a huge plus though.

For those young people interested in a manufacturing career in New York, there are also great programs to put you on a clear path to a good-paying job. High school students can take advantage of the Career Technical Education Industry Scholars Program, which places students with firms like ours. And ApprenticeNYC is a 10-week training program that teaches fundamentals that almost anyone in manufacturing needs to have—blueprints, measuring instruments, and safe workplace training. We have benefited greatly from these programs, often hiring students directly from them who have gone on to take important roles at our companies.

So, for students and others looking for a well-paying, interesting job in an innovative information-age field, there is no reason to leave New York for Silicon Valley. Technology has changed manufacturing in New York. We are not the past; we are the future. And our potential for growth and success is limited only by our innovation, imagination, and finding the next generation of New Yorkers looking to build things in the greatest city in the world.

***

Thomas George is the Vice President of Technology at Quadlogic. Al Mangels is the President of Lee Spring Company and a member of the Executive Board of the NYC Manufacturing and Industrial Innovation Council (MaiiC).

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Governor's Dilemma: Gimmicks or Gumption

(photo: Governor's Office)

Next week Governor Cuomo will unveil his proposed budget for the state fiscal year beginning April 1. In his November modification of the current year’s budget and financial plan there was a preview of the severity of the problem he faces: a significant deficit -- originally $6 billion, now reduced to $4 billion in the current fiscal year, which ends in only 12 weeks -- that is projected at $6.1 billion for next fiscal year and to grow to more than $9 million in 2023.

The governor has acknowledged the magnitude of the budget challenge and hinted that serious structural changes are needed, but it is far more likely his budget will contain a variety of short-term fixes and avoidance devices to close the gap.

Much attention has been paid to the fact that state deferred $1.7 billion in Medicaid expenses from fiscal year 2019 to 2020 to address the recent dramatic increases in the program’s costs. The current deficit is being papered over by again rolling about $2 billion of expenses into the next fiscal year, as well as cutting Medicaid reimbursement rates across the board by 1% and achieving other unspecified savings.

But these fixes are by no means sufficient to handle the cumulative deficit over the next four years, estimated at $28 billion, the largest faced by this governor since early in his first term.

The size of the deficit and the governor’s vague comments in two public appearances last week have created a high level of anticipation and anxiety about the impending budget proposal. The leader of the State Assembly, Carl Heastie, is talking about higher taxes on the wealthy; Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins has been less enthusiastic about more taxes but has not proposed an alternative.

After his January 6 speech to the Association for a Better New York in New York City, I asked the governor if he expects to raise taxes to deal with the deficit. His answer was an unequivocal “No.” He continued:

“We have equated politicians’ response, ‘well we have a problem, the answer is more money’ - no. There’s not necessarily a correlation between more money and better product...the answer isn’t always more money. It’s government’s answer...it’s a legislative answer because they don’t have executive control, so the simple answer is ‘we have to make education better, I’m spending more money’ — we’re already spending more money per pupil than any state in the United States of America, but you’re in the middle when it comes to performance, so the answer’s not always more money. And some of these situations are structurally problematic. We have a problem with Medicaid that is going up very high. A one-shot cash revenue is not the answer - fix the problem. Money tries to paper over the problem, and I’m not in the papering-over business...we’ve been able to say ‘We have reduced your taxes on the state level,’ and I want to continue to be able to say that. Money is not going to solve our Medicaid problem, the health costs have to be addressed structurally, and a one-shot dose for the system of sugar to give us a short high with revenue is not the answer.”

I couldn’t agree more! The audience cheered. But do we all mean the same thing when we talk about the need to address “structural problems”? Probably not.

Two days after the ABNY speech the governor delivered his official State of the State Address in Albany. It contained many quintessential Cuomo elements, i.e. assertions that progressive government must be pragmatic and appeals to the can-do spirit of New Yorkers to build big. With respect to the deficit, he again made generic references to correcting “structural” problems that raised more questions than answers.

First, he was critical of the way state school aid is distributed, noting derisively that it is not progressive and that some districts spend more than $30,000 per student while others spend far less because they lack sufficient resources derived from property taxes. He repeated several times as if a mantra: “use state funds to raise those at the bottom.” The audience cheered; again, who could disagree? But how does the governor mean to rationalize school aid to make it truly progressive and save the state money?

School aid is the second largest expenditure in the state budget, totaling $27 billion a year. It has grown 37% over the last decade. The reason it is so high is that everyone from the teachers unions to parents/voters to the State Education Department to every district’s legislative representatives wants more money for schools every year. A major issue in every budget negotiation is not how much more school aid is needed but rather, how much less than advocates demand is acceptable to the Legislature.

Giving less — or at least no more — to the property- and income-rich districts and to those that have lost school population, and redirecting the savings to poorer districts that need state aid to have enough to provide the sound basic education promised to all students by the State Constitution would mean total school aid would need to rise by only $300 million, not the billions demanded by advocates, saving $800 million, maybe more, per year. It would be very surprising, if welcome, if this is what the governor proposes.

Second, at the very end of the State of the State Address the governor blamed the recent dramatic increase in Medicaid spending – the largest expense in the state budget, which has grown an average of 6.3% per year over the last four years – on the fact that the amount localities contribute to the program is capped and the state has borne all the increases in costs since the cap was imposed in 2015. He cited the amount this saves Erie County ($177 million), Westchester ($175 million) and New York City ($2 billion), wise-cracked “it is too easy to write a check when you don’t sign it” and stated that we need to pay for healthcare “‘intelligently and prudently.” If the local expense cap is the structural problem with Medicaid he means to fix, he is on the wrong track.

Medicaid spending is driven by state policy and health system practices, not by administrative costs at the county or New York City level. New York State has, and has been proud of, its relatively generous eligibility and benefit levels, which mean that there are a whopping 6 million New Yorkers on Medicaid — one of every three residents — and it is the state’s largest expenditure, costing $80 billion a year (half federally reimbursed), accounting for more than one of every three dollars in the state budget.

It is entirely appropriate to ask for more help from localities in curbing misuse and fraud in the program and the governor wisely announced that he will reconvene the Medicaid Redesign Task Force that was effective in achieving Medicaid savings in his first term (bring back Jason Helgerson!).

But there is no justification for pushing costs down to the localities which have even more limited sources of revenue than the state and already pay more of Medicaid costs than the rest of the localities in the country combined. Indeed, freezing the local share of Medicaid to the amount they paid in 2015 and taking full state responsibility for the operation and cost of the program is one of the most significant accomplishments of the Cuomo administration. The Legislature already rejected an effort to lift the cap on New York City’s share when the governor tried to do so in 2016.

One of the sources of the recent dramatic growth in the costs is the state’s directive to pay all home health aides and other Medicaid direct service providers a minimum wage of $15 an hour – immediately in the metro area and over time in the rest of the state — which added $1.5 billion to the budget in this fiscal year, growing to almost $2.3 billion additional in 2023. This may have been a good policy decision but it was not accompanied by commensurate systemic savings that would keep the growth in program spending manageable. Another is the fact that as the population ages, more and more people need long-term care, at home and in nursing homes.

I know several people whose parents or relatives have transferred their resources to family members and taken other measures to qualify for Medicaid to pay for their long-term care, which is now responsible for almost half of the state’s total Medicaid costs. I am sure the same is true for some readers of this column. Indeed even presidential candidate Senator Amy Klobachar said in the debate this week that she expects her mom to go on Medicaid eventually.

Can we expect the governor to propose ways to cut down on the use of personal and long-term care or to tighten Medicaid eligibility requirements? This is no more likely than a structurally reformed school aid plan.

Why should a locality and those taxpayers who live there be financially punished because it happens to have a particularly large share of the state’s low-income population and hence its Medicaid enrollees? Is this progressive government? Why is it OK for state tax dollars to go to economic development efforts to shore up upstate economies that need it but not OK for state revenue to fund needy Medicaid recipients wherever they live in the state? That is not structural reform, but only shifting a serious and growing financial responsibility to another level of government.

So, get ready for a deficit reduction plan that includes cost shifts to New York City, to public authorities, and to capital spending, along with accounting gimmicks, optimistic savings estimates, and other tactics that avoid difficult decisions that would make some legislators and constituents unhappy. I hope I’m wrong.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.