Jay Kriegel’s Unmatchable New York Ethos

Jay Kriegel, 1940-2019 (photo via ABNY)

Jay Kriegel wasn’t a New Yorker, he was New York. In Jay our city was personified, embodied, embedded, in a being the likes of which we will ever know again.

The architecture of his hair alone—towering, iridescent, and high density—distinguished him from the mere mortals who ply our sidewalks, most of whom he knew. Walking Midtown with Jay was like being Mick Jagger’s wingman. From sales clerks to senators, he knew them all, and they all adored him. Ordering a meal with Jay was theater. By the end we knew everything about our server, where they were from, where they had studied acting, and how enamored they were, man or woman, twinkly-eyed, of Jay.

Never mind that for the sake of work we were having breakfast in the Regency surrounded by the self-important; to Jay our server held much more currency than the context, because he knew the actual backbone of New York.

Like so many of Gotham’s now-graying urbanists, I first met Jay while I was employed in the first term of the Bloomberg Administration and he was running the Olympics bid. He was our Yoda. Grouchy, mischievous, brutally honest, there was no bullshit with Jay. For all the pedigree we imported from the halls of Cambridge or Berkeley or Ithaca or Ann Arbor, it was no match for the wisdom of the streets that was Jay’s mastery.

Once he counseled that I should get my shoes shined during rainy weather to protect them, contrary to those who shined their shoes to look good on sunny days. “Rookie mistake,” the pro quipped.

Humility was Jay’s prime directive. In a city of dense egos and vainglorious masters of the universe, Jay was the master of self-effacement. It is this lesson, the hardest lesson for so many of us, that Jay exuded.

As Roy Bahat, a once Jedi apprentice, recently noted in his beautiful essay, for Jay it was about them, not you. Furthermore, this humility, if it was to be authentic, had to be anonymous—there would be no virtue-signaling for Jay. For the innumerable people he had helped, from young students of limited means to we rookies of limited wisdom, there would be no accolades or likes in return for the shelter of his wings. Humility demanded closed door, whispered telephone conversations that led to unrewarded action, as I would learn so personally.

While working with Jay, my spouse Maria and I decided we wanted to adopt from India. Many of the principals around us were skeptical—why gamble with adoption when we already had a biological son? But not Jay. He loved the idea from the outset and would follow its developments daily. Had I heard from the adoption agency? What is the condition of the orphanage? Were there doctors near? Then a magic moment arrived. An email. The agency had identified for us a beautiful three-month-old girl. A photo. Double-click. Two massive eyes pierced the screen. I’m not sure who was more in love, me, Maria, our son, or Jay.

Eight months passed when the adoption agency called: her paperwork was finally ready, it was time to fly. Days later, my heart beating like hummingbird, Avia and I met for the first time. Calamity struck when we flew to New Delhi to get a visa from the U.S. Embassy. Ironically while the Indian bureaucracy had processed her paperwork, the American bureaucracy hadn’t. Embassy staff callously explained that we couldn’t leave India for at least eight weeks, an impossible timeframe.

Panic stricken, I had one instinct: call Jay. It was 10 p.m. in New York, when I knew his long nights typically began. The consummate fixer, Jay was sleeplessly, passionately on it. Days went by until the hotel phone rang. It was the senior consular officer, politely inviting us to the embassy to speak in person.

“Mr. Chakrabarti, who are you exactly?”

“I’m an architect from New York.”

“Mr. Chakrabarti, in the last 48 hours this embassy has been inundated with emails and phone calls from around the world, from Condoleeza Rice’s office, from the Carlyle Group, from several ambassadors, from...”

I smiled silently, picturing Jay working the phone like a lightsaber. Avia and I were on a flight two days later, home before Christmas, as was the enormous stuffed Orangutan that Jay and his dear Kathryn had sent as a homecoming gift.

I am ever aware that the unconnected could never have pulled off what we did, and that this was both unfair and much the way of the world.

Jay, a man of a different generation, from a different New York, understood both conditions, understood this liminal zone between aspiration and reality. He knew that we should always fight for fairness, but we also should help whom we can when we can in this unjust, untidy world.

Jay’s New York understood humanity without binaries—to him there was good in both Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses. Much like Jay’s hair, between black and white was not the gray of compromise, but the silver of wisdom. At his knee we learned that the real dark side of the force were those who lived in a world of absolutes—those who fought against change at all costs, or those who fought for profit over everything. His is a lost ethos today, drowning as we are in the toxic, humorless rhetoric of absolutism.

For Jay the only absolute was New York itself. His desire for the success of each and every New Yorker eclipsed all else. The contagion of his wit and generosity spread to most of us fortunate enough to have been in his orbit, yet none of us can be Jay, none of us can come close. We can only aspire to embody Jay Kriegel’s undying spirit, a giant walking into the sea, taking with him a New York we can only hope to someday recover.

***

Vishaan Chakrabarti is an architect and author. On Twitter @VishaanNYCA.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Worrisome City Budget Update Buried by Holiday and State Woes

Mayor de Blasio gives a budget presentation (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photo Office)

It is an axiom of media relations that when you don’t want something to get a lot of attention, you make it public at a time when few will be paying attention. So, the Friday before last week’s Thanksgiving holiday, when reporters and news consumers were getting ready to greet family, cook and/or travel, both Governor Cuomo and the Mayor de Blasio announced unsettling budget reports.

The governor released an update to the state’s four-year financial plan (required by law on October 31 but usually issued a few weeks late) and the Mayor released the required November mid-year modification to the current fiscal year (FY 2020) budget and revisions to the city’s financial plan for the subsequent three years.

This play did not work very well for the governor because the news was dramatic enough to overcome the timing of its release: due to the tremendous growth in the cost of Medicaid, the state’s operating deficit for the fiscal year that will begin on April 1, 2020 is now projected to exceed $6 billion and grow to $8.5 billion in 2023.

The mayor was more fortunate in that he did get by with very little news coverage of his budget revisions. But that doesn’t mean this information was unworthy of attention and concern. City spending in the current fiscal year is now expected to be $1.6 billion higher than was planned in the budget adopted by the City Council last June, a budget that was already $94.9 billion, or 3.1% more than the budget for the previous year (using Citizens Budget Commission’s adjusted figures).

In the course of the last six months, the mayor, often together with the Council, has announced a number of new initiatives and program expansions, for example higher wages for pre-kindergarten teachers and public defenders, criminal justice reforms (some required by state legislation), more mental health interventions. All of these efforts come at a cost, frequently including new hiring, and the cumulative impact can now be seen in the budget modification.

Headcount is up 1,148 positions in just the last six months. Current total city budgeted headcount is 334,581, growing to 336,005 in FY 2021, and 338,000 in FY 2022 and FY 2023 -- far exceeding the peak before the 2008 recession of 311,018. Not only do all these new hires mean more payroll now, but they will also go into the base for calculating the cost of city-provided pensions and health care benefits far into the future.

The mayor promises to offset much of the increased costs with savings, but most of the offsets are from interest re-estimates on debt service and reimbursements from the state and federal governments, not recurring efficiencies. Indeed, the administration’s commitment to achieving savings is waning: this November citywide savings plan is only 73% of the plans issued in November 2017 and 2018. Are there not far more ineffective or outmoded programs, procedures, and services that can be improved, streamlined, or eliminated?

It is good news that personal income and business tax revenue are projected to grow and that federal reimbursements and grants have been received to offset some of the new expenses, but neither will continue indefinitely and the possible negative impact of the severe change to the SALT deduction and newly adopted rent regulations on property values, on which much of city revenue depends, is yet to be determined.

Most worrisome is that the increased spending included in the November city budget modification is likely only a preview of even more spending growth. There is still time between now and the adoption of the final budget for the next fiscal year (due by June 30 2020) for there to be even more new initiatives added on that will need to be paid for with city funds.

In the FY 2019 budget cycle, between November 2018 and June 2019 the mayor and City Council added $2.5 billion to the annual budget. The increase over the same time period in the most recent budget cycle was $1.6 billion. If the mayor and Council speaker continue this pattern in the coming months, the FY 2021 budget could grow by another $2 billion or more by June.

With the state facing precarious times, it could well implement cuts to state-funded programs like Medicaid and school aid. Under the current circumstances, it cannot be expected that the federal government will help the state or city with budget shortfalls. To be prepared we need more reserves, more efficiencies, and an end to endless hiring.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Greenway for Queens

(rendering: DLANDstudio)

In the heart of Queens there is a 3.5-mile strip of abandoned railroad track that represents the promise of transformation. No train has traversed its overgrown rails since 1962. A mature forest of trees towers above the derelict tracks. Weeds and wildflowers poke up amid the trash that has been dumped there.

It is a space that could better serve some of New York City’s most diverse communities and show that every neighborhood deserves a great park and a safe place away from cars to walk, run, and cycle.

The Trust for Public Land, Friends of the QueensWay, and the Queens Chamber of Commerce are solidly behind a plan to develop this neglected swath of industrial infrastructure into an imaginative greenway with outdoor classrooms, tree-canopied walkways, picnic areas, bike paths, jogging trails, four-season landscaping, and year-round nature-based programs.

A greenway park will carve a calm, welcoming river of plants and paths through Central Queens; improve air quality; moderate increasing summer temperatures along its route; create a safe right-of way for schoolchildren; provide traffic-free pedestrian and bike routes to existing transit hubs; extend the beautiful oak forest and lively amenities into communities; and stimulate the surrounding area’s economy and businesses.

The QueensWay will be a great New York park that takes its character from the diverse communities that it ties together.

It’s time for Mayor de Blasio to say “Yes” to The QueensWay and include preliminary funding in the upcoming city capital plan. Further delay, while other boroughs see investments in greenways, is unjustified and unfair.

For decades, the 47-acre abandoned line in Queens has slipped deeper into decay as decisions about its fate were debated and delayed. But a critical evaluation of the potentials and possibilities for the rail line is in—and the evidence is clear. The MTA took a hard look at the cost and the benefits of rebuilding the railroad corridor for rail traffic and determined the prohibitive price tag for railroad restoration could exceed $9 billion, and that any transit benefit from reopening the line would be minimal at best.

That sticker shock doesn’t even factor in the additional costs and impact on the homes, businesses and commuters that would be affected. As the MTA noted but did not factor into its cost estimate, construction would take years and would close roads, sacrifice community spaces like the Forest Hills Little League facility, disrupt and slow service on existing train lines, force nearby residents to cope with an active railway just steps from their houses, evict commercial tenants beneath the viaduct, clear cut a winding stand of 60-year-old trees, and alienate at least seven acres that are designated parkland.

That finding—that we can’t justify the high cost of reconstructing the 3.5-mile corridor as a useful rail line—removed the last questions about the direction we should take. A park on the old rail line is shovel-ready and the long-unused bridges, rails, and viaducts can be adapted without major disruption to the surrounding area. The QueensWay will cost less than two percent of the cost of rail reactivation. Most important, the idea has widespread support in the community.

This is the moment to acknowledge the extraordinary gift of an open, expansive linear greenway and reclaim the desolate space as a place for people. A greenway for Queens is a celebration of resilience, of the trees and plants asserting themselves along the old rail line, of the people eager to embrace an opportunity to transform an eyesore into a dynamic resource, and of a borough whose time has come. Now is the time to make The Queensway happen.

***

Carter Strickland is New York State Director of The Trust for Public Land; Travis Terry is President of Friends of QueensWay; and Thomas J. Grech is President & CEO of the Queens Chamber of Commerce.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Seeds of Campaign Finance Commission Debacle Planted in Broken State Budget Process

Heastie & Cuomo (photo: governor's office)

This week, the state campaign finance commission, created out of the backroom dealings of the 2019 budget process, released a set of flawed recommendations for a small-donor public matching campaign finance system despite workable alternative recommendations provided by experts and activists alike. In addition, by deviating from its primary mission by focusing on a petty attempt by Governor Andrew Cuomo and his allies to eliminate third parties like the Working Families Party, the commission made a mockery of the countless hours spent by New Yorkers who showed up at hearings across the state.

It should never have gotten to this point. For years, a majority of members in the Assembly said they supported public financing. The newly elected Senate Democratic majority campaigned on plans to uplift the voices of everyday New Yorkers. The governor has claimed support for public financing for years. And make no mistake, the pillars of a strong public financing bill exist.

The Legislature squandered the chance during the legislative session to introduce and pass a gold standard bill drafted by the Brennan Center, which unlike the commission’s recommendations, would have more thoroughly reduced the influence of big money donations in our politics and more effectively enabled new voices to run for office.

So how is it possible that the details of a widely supported democracy reform policy could be left in the hands of an unelected, undemocratic commission in the first place? I’d argue it was 15 years in the making.

The state budget is built on the power of appropriations, allocating specific funds to specific purposes. You might think that in a functional democracy, the elected officials that New Yorkers vote for and send to Albany would have a shared responsibility in that process. It seems only logical that the Legislature and the Governor would negotiate a budget that’s consistent with their constituencies’ desires. But in New York, this is simply not the case.

In 2004, the Court of Appeals issued a decision in Silver v Pataki that laid out a division of power between the executive and legislative branches that has enabled the Governor to wield tremendous control over the New York State budget and appropriations. The court’s interpretation of the separation of powers in the state constitution means that when it comes to appropriations bills, the Senate and Assembly can only reduce or fully eliminate the Governor’s proposed spending. And while the Legislature can add proposed spending, the Governor has the power to veto those additions.

Throughout his time in office, Governor Cuomo has tested the limits of this interpretation, introducing more and more policy and reform into appropriations bills, insisting on “on-time” budgets, playing legislators off each other, and creating an untenable position for legislators fighting for a more progressive budget. With very little leverage to negotiate modifications, legislators must choose between accepting the governor’s austerity driven budget packed with oft-watered-down policy, or shut down the government.

However, the Legislature, including the latest Democratic majorities, has also been complicit in the creation of our broken budget process. Complex policy decisions are jammed into the budget, even outside of appropriations bills, which enable legislators to avoid public scrutiny on the final make-up of the legislation being passed and to provide cover for controversial votes.

The Governor and Legislature are collectively responsible for punting campaign finance reform to this unelected commission. And it was amid the backroom compromise, enabled by Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie and Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, where the governor incorporated language that opened up the potential for the commission to weigh in on political party qualifications. The final recommendations from the campaign finance commision have now validated the fears of those who rightly saw the commission as a mistake and the party-related language as an unnecessary, dangerous sideshow.

So where do we go from here?

First, there are two paths forward in overcoming the Court of Appeals decision issues on Silver v Pataki. One path is a re-litigation strategy aimed at overturning the previous ruling. But the surest way to tackle this challenge is through a constitutional amendment, introduced and passed in two subsequent legislative sessions.

Some will tell you that challenging the Silver v Pataki decision is an uphill battle; that the likelihood of a constitutional amendment passing a Legislature fearful of the Governor’s blowback is low. But it wasn’t that long ago that another power dynamic, widely considered unbeatable, held our state back from delivering on a vision of a fairer, cleaner, and more equitable New York. Yet in 2018, New Yorkers worked together to shine a light on the Independent Democratic Conference (IDC) and organized to eliminate its stranglehold on the State Senate.

Second, it’s time for New Yorkers to turn their attention to the state’s budget process and demand a true commitment to transparency. Public policy should not be negotiated behind closed doors. The historical “three men in a room” budget negotiation was meant to be upended with the election of our first woman leader of the State Senate, but sadly much of the negotiations of this past year’s budget remained as opaque as recent years.

In 2020, legislators and insurgent candidates will have another chance to share their visions for our state. If they don’t acknowledge and rally against the Governor’s overreach in budgetary powers enabled by the Silver v Pataki decision and commit to removing policy negotiations from the budget, their broader campaign promises should be taken with a hefty dose of skepticism.

Years from now, I hope we will look at the failures of the 2019 state campaign finance commission as the breaking point that led to a re-alignment of power in Albany; the moment when New York’s undemocratic budget process hamstrung the state’s ability to lead the nation in expanding and strengthening our democracy.

***

Ricky Silver is the co-lead organizer of Empire State Indivisible. On Twitter @es_indivisible.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

National Grid Deal Shows Best and Worst of Cuomo

Gov. Cuomo (photo: Mike Groll/Governor's Office)

The saga over the National Grid moratorium on gas hookups illustrates both the best and worst of Governor Andrew Coumo.

The fact that Cuomo was able to get the utility to back down from its moratorium, despite the long-term facts being on its side, is exhibit A that Cuomo is a master politician. He knows how to play the game and to control the spin. On the other hand, it once again reminds us of the governor’s penchant for egregious pandering to special interest groups he is courting and the eventual harm that it will cause to the welfare of the state.

Early in his first term, Cuomo followed through with his promise to be a strong fiscal manager. He clamped down on extravagant healthcare increases and earnestly sought to keep state spending within a self-imposed limit of 2% annual growth. He shepherded through a very much needed property tax cap, even though he exempted New York City from the constraints.

But, as time went on, he saw that it was the radical left that was gaining momentum in the state, and fearing a primary defeat at the polls, he switched gears. His early devotion to spending limits morphed into a bunch of budgetary gimmicks whereby he claimed he was staying within his 2% threshold, but was actually spending at twice that pace. A glaring recent example is the disingenuous machinations he’s employing with Medicaid by shifting present costs into future years and a ballooning deficit.

Then there was his earlier pandering to environmental extremists, starting with his putting the Kibosh on fracking in New York. This was devastating to the upstate economy. While Pennsylvania and Ohio communities flourish thanks to fracking, New York upstate communities continue to languish in a forgotten Rust Belt status. And it was all to boost his bona fides with the radical greens, whom he did not want dogging him during his reelection bid and he perhaps hoped would support him in a potential run for the presidency.

While he’s not running this year, those ambitions likely weigh heavily on his mind, as he recently declared war on not only National Grid but also Con Edison in their efforts to get needed pipelines laid to bring residents and businesses natural gas to heat their homes and stores.

The governor’s reasoning is purely political and downright dangerous. National Grid is not making up the fact that more capacity is needed to fuel our growing energy needs. A pipeline is the safest and most affordable method of transporting gas. Yet, Cuomo had his agency block the laying of the pipe on the most specious environmental arguments that it will somehow pollute our waterways.

Ironically, the deal that he has struck with National Grid to end its moratorium calls for the needed supply of gas to be brought into our area via tractor-trailer trucks.

Is this a joke? Has anyone calculated the carbon footprint of adding all of these tractor-trailers onto our already congested roadways?

Cuomo has his checklist: there’s something for every interest group, with the environmentalists getting a pie in the sky effort to eliminate natural gas and other fossil fuels over the next few years.

The irony is that it is natural gas that is responsible for the United States being one of the only industrialized nations to have actually reduced its carbon footprint over the last 15 years. It simultaneously made us energy independent from Middle East tyrants, while boosting our economy and making us the number one producer of energy worldwide.

Solar, wind, and other alternative sources certainly must be in our energy portfolio, but it is pure folly to believe that we are prepared at this point to shut the spigot off the natural gas pipelines.

Just because National Grid can continue to supply new hook-ups with needed gas does not mean that we aren’t heading toward a crisis without necessary pipelines. Many will look at this deal crafted between Cuomo and the utility as putting the controversy to rest. To the contrary, the headaches have just begun.

The New York Post reported just last month that Public Service Commissioner John Howard conceded: “This short-term reaction was, `We need more gas.’ That’s an undeniable fact.” Another Commissioner, Tracy Edwards, admitted: “We have capacity issues.” And a third, Diane Burman, said: “Those who say ‘No new pipelines’ should look at what the ramifications are.”

Cuomo comes out the victor in the short-term by making National Grid bow to his aggressive ways, including the threat of imposing even heavier fines and revoking their license to operate in New York. (Though I wonder if his strong-arm tactics would have held up in court, had National Grid maintained the resolve to take it to the next step.)

Nevertheless, with the assistance of a politically-aligned liberal Attorney General's office, the governor adroitly put the utility in a corner. The utility lost this round and Cuomo put another notch in his belt, but in a few years when our utility rates go through the roof and supplies are once again threatened, it will be the residents and businesses of New York who will be the real losers.

***

Steve Levy is President of Common Sense Strategies, a political consulting firm. He served as Suffolk County Executive, as a New York Assembly member, and host of "The Steve Levy Radio Show." He is the author of “Bias in the Media” and is on Twitter @SteveLevyNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York City Needs a Development Reset – Starting with Public Land

City-owned building at Vernon Blvd & 44th Dr (photo: Memo Salazar)

2019 may go down in history as the year public disenchantment with New York City’s land use policies reached a boiling point.

In June, protestors disrupted a meeting about a neighborhood study for a potential rezoning on Southern Boulevard in the Bronx, claiming that city agencies did not really want their opinions. In August, a judge heard arguments in a lawsuit challenging the 2018 Inwood rezoning, with groups in that Upper Manhattan neighborhood charging that the environmental impact study undertaken there was illegitimate. In September, resident groups publicly assailed City Council Member Carlos Menchaca when he proposed to enter into community benefits negotiations with Industry City Associates, which had applied for a private zoning change in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park. That same night, Queens activists turned an Economic Development Corporation-sponsored meeting about the Sunnyside Yard master plan into a raucous “teach-in,” loudly expressing their conviction that the city was failing to elevate the public interest over the aims of real estate developers.

What explains this increasing lack of faith in government’s good intentions?

Part of the problem, as others have pointed out, is that the city has no framework with which to strategically coordinate land use changes and infrastructure investments. Without a comprehensive planning process to guide investment decisions and resolve equity tradeoffs, the city’s moves to densify and develop in particular neighborhoods are met with fear and protest.

But also part of the problem is the de Blasio administration’s outdated mindset with respect to development more generally -- particularly development on land owned by the city. The practice of selling publicly-owned sites to developers to raise revenue, and to promote the creation of new, mostly market-rate housing and office inventory, became commonplace under Mayor Michael Bloomberg. The de Blasio administration has continued the practice, frustrating those of us who believe there are better uses for public land.

To take one example: in Long Island City, Queens, a battle is brewing about the fate of two sites in Anable Basin. Located on 44th Drive close to the waterfront, they are currently owned by the public. But they have a history: in 2018, the city’s Economic Development Corporation had issued requests for proposals or requests for expressions of interest for them, and come to a preliminary agreement with the development firm TF Cornerstone to build and operate a mixed-use development (with residential, commercial, and some industrial uses) on one of them. Then came Amazon. Last November, the sites appeared on the map of the planned HQ2 campus.

When the Amazon deal fell through in February of this year, the city went silent, and local activists (many of whom had fought HQ2) started thinking not just about what they didn’t want in their neighborhood but about equity-positive alternatives.

Last summer, a coalition formed around the aim of creating a Community Land Trust (CLT), which provides a vehicle for permanently affordable development managed by mission-driven organizations. The land trust activists developed a plan to renovate one of the city-owned sites – a 638,000 square foot industrial building at 44th Drive and Vernon Boulevard – as a multi-tenant space for small manufacturers, working artists, a commercial kitchen, and a school. A non-profit partner selected to operate the space would be subject to a special deed, drawn up by the land trust, that compels them to charge below-market rent in perpetuity to the kinds of tenants who are currently being displaced from Long Island City in droves by luxury development.

Judging by the YourLIC planning exercise announced last month, the city appears to have other plans for the sites the public owns in Anable Basin. But before things go any further, the de Blasio administration should consider conveying the site at 44th Drive and Vernon Boulevard to the Western Queens Land Trust.

On land it owns, the city should be leading by example, fostering development that creates family-supporting jobs and offers open space and public facilities (like schools) without contributing to gentrification and displacement. An indication of what is possible in Long Island City can be seen on the activists’ website, OURlic.nyc.

We have set the bar too low for too long. Using public land, the city can subsidize development that improves communities without making them unaffordable to the people who currently live there. This path is not the most lucrative option in financial terms. But the highest and best use of land need not always be the use that commands the highest investor return. In Long Island City and elsewhere, conveying city-owned property to land trusts and other mission-driven organizations is an investment in neighborhood value that could help earn back the trust of the currently disenchanted.

***

Laura Wolf-Powers is an associate professor in the Department of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College. On Twitter @wolf_powers.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

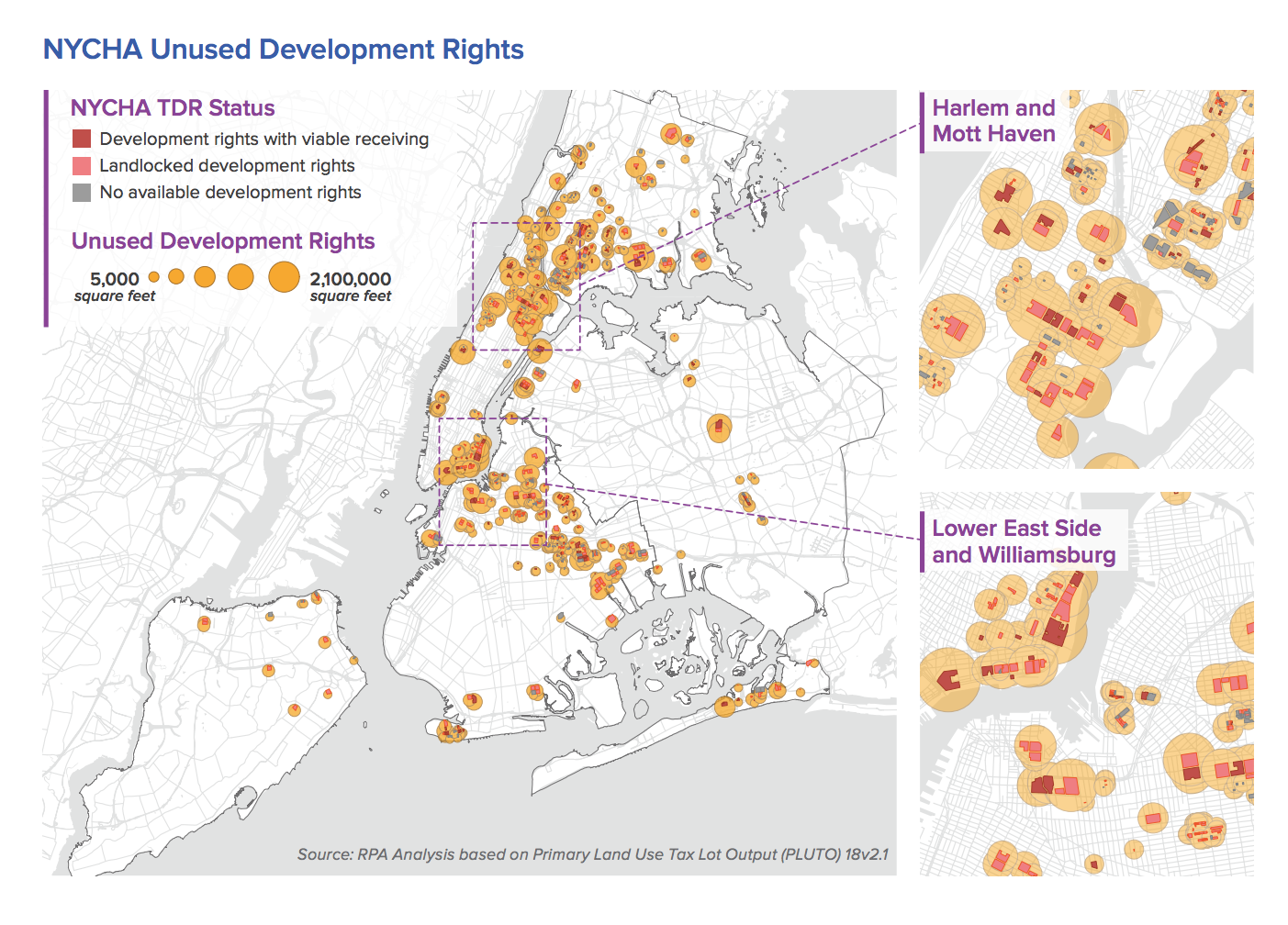

Hidden in Plain Sight: Billions in Potential Revenue for NYCHA

(East Harlem NYCHA superblocks possess massive amounts of unbuilt air and ground space, as illustrated in the HOUSING DENSITY show currently on view at the Skyscraper Museum.)

NYCHA developments full of high-rises seem massive from a distance, but on closer examination their visual bulk disguises a deeper truth: they are dominated by open space. What to do with all this unbuilt space has inspired competing and controversial plans for infill and redevelopment. A growing number of policy experts believe that the New York City public housing authority would benefit just as much from a more aggressive program to transfer development rights for cash. They are right.

That NYCHA is “underbuilt” has been known for decades, but the general consensus has been that the rules governing Transferable Development Rights made it impossible for the housing authority to monetize the unbuilt square footage. Large NYCHA superblocks frequently lack adjoining parcels to which these rights could be transferred under current rules. NYCHA, to most eyes, appeared to be landlocked.

Intrepid staff at the Regional Plan Association have now calculated that a straightforward rule change (a city Zoning Text Amendment) could put into play an astounding 78 million square feet of NYCHA’s transferable rights. Selling these rights, they estimate, could yield $4.2 to $8 billion for NYCHA repairs.

The key to unlocking these revenues is to allow the authority more flexibility than typical property owners in moving its Transferable Development Rights around the city. By moving NYCHA air rights across the street, up to a half mile away, or within a Community District, the opportunities for revenue generation increase exponentially.

(Image Courtesy Regional Plan Association, Time to Act)

(Image Courtesy Regional Plan Association, Time to Act)

These eye-popping revenue projections could be game-changing when it comes to paying for much-needed repairs of boilers, apartments, and more.

Relying more on development transfers would also defer a growing number of pitched battles over infill and redevelopment. As illustrated in the HOUSING DENSITY exhibit at the Skyscraper Museum, low-density NYCHA superblocks (even in their rundown state) offer current residents a style of living that is difficult to replicate anywhere else in New York. Where else in the city can you find relatively large apartments (avg. rent $533 per month per apartment) with windows in every room looking out on open space, trees, and the city?

Infilling NYCHA with new structures will not only take away some of the city’s last open spaces, and tree canopy, but will further undermine the remaining quality of life for current NYCHA residents. Less air flow, fewer trees, and reduction in permeable surfaces seems like a bad idea for a warming city. Infill projects are, therefore, stalling out for a good reason. Redevelopment projects of buildings and grounds offer a brighter hope for completely rethinking NYCHA’s midcentury tower-in-the-park formula, but so far the politics of redevelopment are even more fraught than infill.

(Johnson Houses in East Harlem: Just one of many NYCHA developments with extensive tree cover and lawns.)

As with all things NYCHA, a major policy shift on Transferable Development Rights will generate enormous resistance -- but probably not from NYCHA residents. Instead, it will be NYCHA neighbors, some of them blocks away from current projects, who will feel the impact. If this proposal moves forward they will find that many builders can upsize their plans for development. Expect a backlash from non-NYCHA neighborhood activists and those that represent them including city, state, and federal elected officials.

Some say the politics would be too difficult and few city leaders have embraced this brave plan as of yet. There is, however, a double standard here that should be addressed. Politicians found a way, for instance, to make similar changes in East Midtown in the name of commercial modernization. Zoning text changes there enriched a few billionaire property owners, and were achieved over some vocal community objections, so why not make similar changes for the benefit of NYCHA’s 400,000 residents?

It is hard, moreover, to have much empathy for city residents and their elected officials resistant to finding alternative funding sources for NYCHA. It is true that Mayor de Blasio has committed unprecedented local funds to NYCHA, but the City of New York has found much more additional money for generous labor contracts, ferries, new jails, and bike paths, while allowing NYCHA residents to face another winter with very old boilers. If politicians and non-NYCHA residents are unalterably opposed to Regional Plan Association’s proposals, they should at least propose an alternative means of financing the $30+ billion renovations NYCHA needs.

In the meantime, the treasure hidden away in underbuilt NYCHA superblocks should be used as a major downpayment for immediately upgrading resident life.

***

Nicholas Dagen Bloom, Professor of Urban Policy and Planning, Hunter College is author of Public Housing That Worked, How States Shaped Postwar America: State Government and Urban Policy, and a co-curator of the HOUSING DENSITY show.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Commission Failure Shows Need for One True Fix for New York Elections

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Looking at the plan from the state campaign finance commission, anyone who’s had even a passing interest in New York politics is left either scratching their head or gritting their teeth (maybe both). It’s no surprise that the aspects of the commission’s just-completed work that have provoked the most vociferous opposition and passionate debate have nothing whatsoever to do with public campaign financing. On the left and on the right, activists, lawmakers, and good government groups are decrying the elements of the plan that would eventually kill off every minor party in the state and keep other potential new ones from sprouting up.

These recommendations include raising the number of votes necessary to retain ballot access, going from 50,000 to a minimum of 130,000 and making it a biennial rather than quadrennial test. Given recent voting trends, the move would kill off every minor party in the state except one - the Conservative Party. Trust me, as a leader in a political party (the Reform Party) that just lost ballot access under the existing thresholds, I can tell you that getting 50,000 votes is no walk in the park.

Potentially even more alarming, though, is the dramatic increase in the number of signatures necessary to qualify for the ballot statewide, going from 15,000 to 45,000. This increase would reserve ballot access for only the super wealthy or the hand-picked candidates of the political establishment or certain deep-pocketed special interests, very likely keeping new parties from sprouting up (as two did last year to make the ballot: SAM and Libertarian).

If the Legislature allows these new rules to be implemented, it would likely bring an end to New York’s longtime history of having robust and influential minor parties. It’s a tradition that goes back well over a century in our state. So, why do this? Is the public really clamoring for a less crowded ballot with fewer choices? Of course not!

Aside from a scorned governor seeking vengeance on a political rival (Andrew Cuomo and The Working Families Party), there is actually ample reason to think that our current system, where minor party bosses are treated like major power-brokers, doesn’t work well.

We’ve seen time and again over the last half-century example after example of parties with paltry memberships and even smaller vote totals be showered in patronage jobs, direct donations, policy-making roles, and more in exchange for their ballot lines. In some cases fusion voting in this state has produced minor party leaders (baby bosses) who seem like their sole reason for maintaining a party is acquiring of money and patronage, with little regard for anything resembling a coherent legislative agenda.

But to minimize these baby bosses, is it really wise to eliminate the voter options of the Green Party and the Libertarian Party, who rarely cross-endorse major party candidates and provide an important voice for voters that would otherwise be ideologically disenfranchised? No!

Thankfully there is a way to kill off the illegitimate minor parties and their baby bosses without killing of all minor parties and the valuable options they provide to voter: non-partisan elections.

The state Legislature should immediately pursue a shift towards non-partisan elections in order to provide New Yorkers with real choice and competitive, more thoughtful elections. It would work similar to how special elections are run in New York City, and elections in cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and Houston, and even cities here in New York like Watertown and Sherrill.

Here’s the novel concept. Anyone who wants to run for office can run. They’d all run on the same ballot under the same rules -- whether running for Governor, State Assembly, County Executive, etc. There would be no Republican or Democratic line on the ballot, and much to the pleasure of Governor Cuomo, no Working Families Party line (and so on). This would mean that the baby bosses wouldn’t be able to demand a job for their incompetent relatives or demand that candidates buy pricey tables at party fundraisers.

So how does all of this help minor parties and allow voters more choice?

Under a system of nonpartisan elections, without the stigma of running as “third party” or “spoiler” candidates, the candidates of minor parties could actually get broad considered and be elected. If you look at places around the country that have nonpartisan elections, we’ve seen many examples of candidates without the endorsement of either major political party getting elected and in some cases launching high-profile and successful political careers.

These include Jesse Ventura in Brooklyn Park, MN; Dennis Kucinich in Cleveland; Oscar and Carolyn Goodman in Las Vegas and even the current Mayor of San Antonio, Ron Nirenberg. Lest anyone think, though, that nonpartisan elections would suddenly allow the fringes of the political spectrum to have unwarranted access to the levers of statewide policy-making, one should keep in mind that cities like Chicago and Boston have consistently elected establishment politicians, whose major party bonafides are without question.

In discussing a switch to a nonpartisan system of elections, there will be some who protest by saying that seeing a partisan label on the ballot offers voters a clue as to a candidate’s ideological belief system. For those folks, I’d ask: what does seeing both Charles Barron and Dov Hikind running as Democrats from Brooklyn really tell you about their ideology? How about seeing judicial candidates nominated by every party on the ballot?

The bottom line is this: if you want voters to have more choices and minor parties to continue to function, but not corrupt the system, the only real choice is nonpartisan elections for every office across the state.

***

Frank Morano is an activist and radio host. On Twitter @frankmorano.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How to Shop Small This Holiday Season

(photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

The holiday season is upon us and we all know the temptation of online shopping. The ease of getting the things we want at the click of a button might seem harmless, but it has major consequences for local small businesses.

Shopping online takes away from the livelihood of local residents and strips the community of its extraordinary businesses. E-commerce also means you don’t have the ability to inspect your purchases before receipt, you have to go through the hassle of repackaging and returning items you don’t want to keep, and you’re depriving yourself of getting to know the business owners in your neighborhood.

The better way is the smaller way. Shopping small means you’re supporting your community. Small businesses are the backbone of New York’s local economy, with over 230,000 businesses, employing 3.69 million people. Besides contributing to the workforce, small businesses connect communities and help create unique, energetic neighborhoods throughout our city.

As the holiday shopping season approaches, I’m encouraging all New Yorkers to show some love to our small businesses. Here are some ways you can help your local small businesses that extend beyond just your purchasing power:

Participate in Small Business Saturday. Avoid the Black Friday mayhem and shop small on Saturday, November 30.

Pledge Your Shopping List to Your Community. This holiday season make a commitment to buy half of your shopping list from local small businesses. Jewelry, clothing, pottery, and books are all great gifts that can be found in your neighborhood. Consider gifting a “made in New York” basket with your favorite local items.

Share Small Business Content on Social Media. A great way to support your favorite local businesses is to share their content on social media. It can be as simple as posting a picture on Instagram or checking in on Facebook.

Leave Positive Reviews. While word-of-mouth recommendations are always good for small businesses, it doesn’t hurt to leave positive reviews on Yelp and Google. Leave an online review for small businesses to get more traction and visibility.

Join the fun! Participate in seasonal fun on your block and in your neighborhood, or even in another neighborhood you enjoy or are eager to explore for the first time. From tree-lighting events to local gift guides, get involved and shop small.

While you’re preparing for this busy season, remember to continue supporting the diverse, independent small businesses that enrich neighborhoods across New York City. As we enter this busy holiday season, don’t forget to shop small!

***

Gregg Bishop is the Commissioner for the New York City Department of Small Business Services. On Twitter at @NYC_SBS and @GreggBishopNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Right to a Free and Quality Public Higher Education in New York

(photo: The City College of New York)

CUNY has long been the pride of New York City and its cradle of opportunity. But at a recent legislative hearing on higher education in Brooklyn, we heard from teachers, administrators, and students about a harsh reality: After years of state underinvestment in public college, our CUNY system is teetering on the edge of crisis.

Both of us have been blessed with a CUNY education. Yet both of us see firsthand the heartbreak and struggle that many students face when they seek to advance themselves through higher education. In the end, some graduate. Some don’t. And some never get to try because it’s just not affordable.

Students desperately need relief. CUNY’s six-year degree completion rate is only 55%, and financial strain is one of the main reasons students drop out. In a 2017 report on college success, the Center for an Urban Future shared that 75% of dropouts at Kingsborough Community College had a financial “red flag” in their accounts such as owing money or loss of scholarship. To make matters worse, a staggering half of all CUNY students experience food insecurity, and many struggle with housing insecurity or even homelessness.

There’s a reason for this dire situation: Tuitions have risen steadily year after year, as the share of the budget that comes from tuition has grown from 20% to almost 50% over the past 30 years.

In other words, students are bearing the burden of our failure to invest in quality public higher education.

This penny-pinching on the part of New York has led to further consequences. Adjuncts, upon whom CUNY increasingly relies, are grossly underpaid, even with a new contract that would increase the minimum pay per course. The ratio of full-time faculty to students is significantly higher than national standards. Facilities have deteriorated and class sizes have become overcrowded. These trends cause lower retention rates and greater time to graduation.

This is a downward spiral that we must stop.

In today’s age, a higher education is no less necessary to succeed in most fields as a high school diploma was two generations ago. And a college degree is a pathway to economic opportunity and financial security: according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a person with only a high school diploma has nearly double the unemployment rate of a college graduate and earns on average 39 percent less per week.

A CUNY education has been shown to be one of the most successful ways to bring a student from the bottom quintile in family income to the top—with a mobility rate of more than three times those of the most elite institutions.

The struggle of our CUNY students and underinvestment in our CUNY system mirrors the budget cuts for public schools across the nation that occurred after the Great Recession. State funding for public schools across the country is $9 billion below 2008 levels, adjusted for inflation, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Recognizing the necessity of free college, Governor Cuomo and the Legislature implemented the Excelsior Scholarship in 2017, aiming to make four-year college tuition-free for many.

Yet as of 2018, only about 3% of the state’s undergraduates benefited from the scholarship. The majority of applicants who applied were rejected because they didn’t meet the onerous credit requirements.

New York is missing out on future climate scientists, doctors, and other leaders because students can’t pay for rent, food, and a MetroCard without a job, which makes them unable to access or retain the Excelsior Scholarship.

It’s time to transform New York State with a robust promise for free higher education. We did it once before with K-12 schooling and we should boldly aim to do it again by making New York the first state in the country to constitutionally guarantee a free, quality public college education.

Higher education should not be a luxury for the few but a tool for many. Let New York lead the way and make our state a model of what a commitment to public education in the 21st century should be.

***

State Senator Andrew Gounardes represents parts of Brooklyn and is an adjunct professor at Hunter College. Timothy Hunter is chair of the University Student Senate and a CUNY Student Trustee. On Twitter @agounardes & @thunter_tim.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.