Getting a Stop Sign

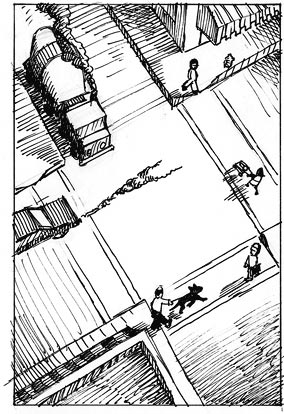

Eleven-year old Christopher Adam Scott rode his bicycle across the pedestrian overpass of the Clearview Expressway in Bayside. As he reached the corner of 46th Avenue and the expressway service road, a car struck him, killing him almost instantly.

Eleven-year old Christopher Adam Scott rode his bicycle across the pedestrian overpass of the Clearview Expressway in Bayside. As he reached the corner of 46th Avenue and the expressway service road, a car struck him, killing him almost instantly.

Six years before, 12-year-old John Shim was riding a bicycle in the same spot. He too was struck by a car and died of his injuries nine months later.

Local residents believe a stop sign could have helped save the lives of both boys.

About 200 pedestrians are killed by cars in New York City every year. Traffic engineers suggest that stop signs can help remedy the problem by regulating the flow of traffic in a busy neighborhood. The New York City Department of Transportation says that stop signs should be used to alert drivers and pedestrians as to who has the right of way.

But stop signs cannot solve all traffic safety problems, transportation experts say. For example, the U.S. Department of Transportation, which sets standards for stop signs and traffic lights, cautions, "Stop signs should never be installed as a routine, cure-all approach to curtail speeding, prevent collisions at intersections, or discourage traffic from entering a neighborhood."

And when they are misplaced, stop signs can make a situation worse. "Studies have found when stop sign are placed at intersections where they are not really needed, motorists become careless about stopping," says an information sheet issued by the Center for Transportation research and Education in Ames, Iowa.

Given all this, there is no guarantee that a request for a new stop sign will be granted. The Department of Transportation suggests that residents who believe their intersection meets the requirements write a letter to Transportation Commissioner Iris Weinshall at the Department of Transportation, 40 Worth Street, New York, NY 10013. The department provides an online form for this purpose.

The department refers the request to the Traffic Engineering Unit in your borough. That office makes a preliminary study of the street corner in question, including traffic and pedestrian volumes, vehicular speeds, accident history and sign spacing. Eventually the unit will conduct a field investigation to observe traffic on the street corner at various times and on different days of the week, over a period of several weeks.

The inspectors want to determine whether conditions at the intersection meet federal standards for traffic lights and signals set out in the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices published by the U.S. Department of Transportation.

The investigation takes about six weeks. Then, if the department approves the request, an installation will be scheduled. The sign is usually put in within three or four months.

This sounds efficient and thorough, but is it really?

Not exactly, says Roe Daraio, longtime activist and president of COMET: Communities of Maspeth and Elmhurst Together.

Daraio estimates that 95 percent of her requests for stop signs have been fulfilled. "You just have to be a little creative," she says.

Simply following transportation department's instructions is not enough.

COMET keeps a close watch on corners and records problems, listening to accident reports on a police scanner. "You should always be able to say what dates and times the accidents occur," says Daraio. "The more clearly you express (the problem) to the agency, the more likely they are to respond."

Typically, she writes to the head of the Queens Borough transportation office, Joseph Cannisi, rather than to Commissioner Weinshall, as the city guidelines suggest. Since Weinshall's office receives thousands of requests each year and forwards them to the boroughs, Daraio says, writing directly to the borough office eliminates one step.

Daraio also advises that the letter provide as many details as possible about the street corner, such as how many children live nearby or if there is a school. She strongly suggests enlisting local community organizations in the quest, because they probably have a working relationship with key officials, as COMET does with Commissioner Cannisi.

The borough transportation office works closely with the local police precinct to assess the need for the sign. To get the police on your side, Daraio advises reminding the police of the frequency of accidents on your specific corner.

Sometimes, DOT decides to install a stop sign — even if community residents would prefer another remedy such as a traffic light. That is fine with Daraio.

"I find that when drivers see yellow lights ahead of them, they floor it,' she said. "We know night drivers don't come to a full stop at a stop sign, but at least they slow down a little."

In deciding between a stop sign and a traffic light, transportation officials consider the number of vehicles that go through an intersection as well as how fast they are traveling. Visibility and the presence of other traffic lights nearby can also affect the decision.

But evidence of need does not guarantee that the city will install a sign — or a signal. The intersection in Bayside where the fatal accident occurred still has no stop sign and does not seem likely to get one. Transportation Commissioner Weinshall told the Western Queens Gazette that, while "it's very tragic what happened with this little boy... federal standards were not met" for the installation of a stop sign or a traffic signal

No one has told community residents what precise conditions the intersection fails to meet.

Since the denial of the stop sign, the city transportation department has taken several steps to try to make the intersection safer. It has, for example, installed cone shaped objects to guide oncoming traffic away from the pedestrian bridge and posted a sign on the bridge advising bikers to get off their bikes and walk across the overpass.

Community residents would prefer a stop sign. And at least some of them think they know why their request was rejected. "This is how politics works — red tape," local Democratic Party activist John Bisbano told the Western Queens Gazette. "All they know is numbers."

(Do you need a stop sign in your neighborhood? Tell us about it by going to the Community Gazette for your area.)

-- Nicole Zaray

|

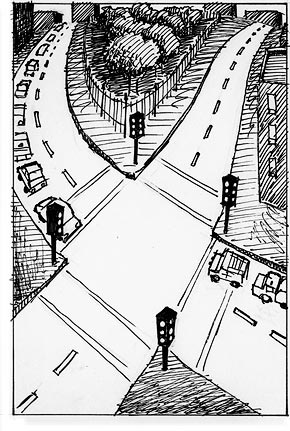

Fixing a Traffic Light

Ken Daniels could hear the horns and smell the carbon monoxide. After eight years of pestering, he had finally convinced the city Department of Transportation to install a traffic light near his Glendale, Queens home — but in September 1999 workers mistakenly erected the device one block from the designated spot.

Ken Daniels could hear the horns and smell the carbon monoxide. After eight years of pestering, he had finally convinced the city Department of Transportation to install a traffic light near his Glendale, Queens home — but in September 1999 workers mistakenly erected the device one block from the designated spot.

A retired senior account executive with a lot of free time and no fear of confrontation, Daniels vented his outrage in community newspapers and on local TV news programs. He demonstrated that the new signal was exacerbating the six-block-long tie ups on Cypress Hills Street and making it impossible for motorists to turn off 71st Avenue, where the two roadways meet in a T.

"Cars were waiting for hours. I was so frustrated I was telling the media I could have done a better installation myself," Daniels recalled.

The commotion convinced Queens Community Board 5 District Manager Gary Giordano, whose office is two blocks away, to help Daniels contact high-ranking Department of Transportation officials. Assemblywoman Catherine Nolan and then City Councilmember Thomas Ognibene wrote letters of support.

Soon thereafter, the Queens borough commissioner of transportation at the time admitted that an error had been made, and in March 2000, the misplaced traffic signal was taken down in favor of a new one at the originally sought location.

Looking back on his fight, Daniels says, "It wasn't the easiest thing, but this shows that when you put your mind to it, even the average person can get something done. That is, with the help of local newspapers, local politicians and the local community board."

Though extreme, Daniels' case points up what is needed to wage a successful campaign for a traffic signal: patience, persistence, a worthy street corner and friends in high places.

According to the Department of Transportation web site, New Yorkers start the installation process by writing to the department's Signal Engineering Intersection Control Unit, 34-02 Queens Boulevard, Long Island City, NY 11101. (A broken traffic signal should be reported to 311.)

Engineers then study the location, considering such factors as motorist and pedestrian volume, presence of senior citizens and children, vehicular speed, accident history, visibility and signal spacing. The data is then analyzed according to federally mandated guidelines.

The study generally takes 12 weeks. If the request is granted, the traffic signal will be installed within six months of approval.

The department may decide not to install a traffic light because a cheaper method, such as a stop sign, would be just as effective. And traffic lights can create problems. A study by the Washington State Department of Transportation, for example, concluded that traffic lights tend to increase accidents where a car collides with the rear end of the vehicle in front of it.

And traffic signals alone may not solve a problem. Transportation Alternatives, a New York advocacy group, notes, "A traffic signal will do little to stop reckless red-light running without consistent police enforcement."

But speeders and reckless drivers should be aware that traffic signals and stop signs are only two of the transportation department's possible remedies. The agency also provides speed bumps, blinking lights, rumble strips, speed-limit signs and other controls. In fact, the department frequently responds to a request for a traffic signal by installing something else.

Whatever it decides to do, external factors can influence the process. A traffic light may be installed more quickly, for example, if there has been a recent fatality. And there is always politics.

Cagey veteran Lew Simon, a Democratic district leader from the Rockaways, always organizes a petition drive and sends copies of the signatures to various politicians and DOT officials along with his signal requests. He has also been known to organize rallies at the relevant crossroads after sending out press releases.

"Sometimes you have to knock down doors at City Hall," he said. "Otherwise, they won't open for you."

(Do you need a traffic light in your neighborhood or is a stop light broken? Tell us about it by going to the Community Gazette for your area.)

-- Rob MacKay

|

NYC Subway Token, 1953-2003

| -- |  |

| -- |

At the transit museum store, you can buy a set of the five "historic" New York City subway tokens, introduced in 1953, 1970, 1980, 1986 and 1995, as well as subway tokens made into key rings, lapel pins, cuff links, bracelets, and money clips. Other stores sell ashtrays, paperweights, drinking glasses, coasters, mugs, ties, t-shirts, Christmas ornaments, even dresses festooned with the image of the token. The People's Hall of Fame, which honors New Yorkers every year for contributions to the city's cultural life, presents inductees with an enormous replica of a token. There are Frisbees shaped like giant tokens. The only thing the New York City subway token will no longer be used for, as of May 4, is to get you onto the subway.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority ended all sales of the token at midnight April 12. On May 4, when the transit fare is scheduled to rise from $1.50 to $2, the 13 million tokens still circulating will no longer be "good for one fare" on the subway, leaving the Metrocard the exclusive currency of straphangers. Bus fare boxes will accept tokens (plus 50 cents) until December 31. Then, 50 years after its birth, the little brass coin will essentially end its working life - except for one small gig: For the time being, tokens will continue to be sold for $1.50 and used at the Roosevelt Island Tram, which is run by the Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation, not the MTA.

The demise of the token has been expected ever since 1994 when New York became one of the last subway systems in the country to introduce fare cards. The blue and yellow MetroCards are cheaper to produce and can be programmed to offer discounts and transfers. Emptying tokens from turnstiles and delivering them to token booths is time-consuming and expensive. Phasing out the token, transit officials say, will save $6 million a year in handling costs. "In this time of dwindling resources, the shift away from tokens will allow us to be more efficient," Lawrence G. Reuter, the president of New York City Transit told The New York Times recently.

And so the clatter of metal tokens being emptied into buckets will soon join the clip-clop of horses on cobblestones, newsboys shouting "Extra" and the nasal intonations of Joan Rivers' taxi tape among New York's many bygone sounds.

|

|||

New Yorkers already seem to have accepted the demise of the token. Few people spoke out on its behalf at hearings this winter on the fare hike, and indeed, by early this year, tokens were already being used for only eight percent of all rides. (There are exceptions: One Paula Glatzer wrote to the Times "I care about the end of subway tokens. I always carry a few with me, mostly for the times my Metrocard won't swipe....Why can't we get dependable readers, like those in other cities?")

The token is sure to live on, as item of nostalgia and icon of New York -- more humble than the Empire State Building or the Statue of Liberty, but a potent symbol nonetheless.

"It says 'NYC' on it, so that's certainly a big part of its appeal, but it's also popular because it's a very democratic symbol," said Sarah Henry, a historian with the Museum of the City of New York, which featured the token prominently in its recent exhibition entitled "NYCentury" on the city's symbols. "Because the subway is so deeply embedded in New York's identity and so many different kinds of people use it, the token by symbolizing the subway comes to symbolize the city." In that way, at least, the token will not be replaced: "The MetroCard," she said with a touch of scorn, "doesn't have the visual presence of the token."

RELATIVE NEWCOMER

The token is so closely identified with New York that most people do not realize that the subway system carried New Yorkers for 49 years before it acquired its own currency. For 44 years it cost a five cents to ride a bus or subway and all riders needed to get on board was a nickel. When the fare rose to 10 cents in 1948, the city refit the turnstiles to accept dimes.

|

|||

But just as technology would eventually doom the token, technological limits created it. In 1953, when the fare rose to 15 cents, engineers could not figure out how to make a turnstile operate with a dime and nickel or three nickels. To solve the problem, they devised their own 15-cent currency.

Those first small tokens set the pattern that would become world-famous. On one side was the legend "Good for One Fare," on the other "New York City Transit Authority." In the center were the letters "NYC" with the "Y" cut out.

That token lasted 17 years, surviving a fare hike to 20 cents, and thousands probably remain squirreled away as keepsakes. Tens of thousands of New Yorkers who reached manhood in the 1950s and 1960s can still recall receiving one of those little tokens in the envelope with their draft notices to make it easy for them to report to the induction center.

In 1970, a larger token, also with a "Y" cutout, debuted along with the 30-cent fare. A decade later, when the fare reached 60 cents, a solid token with a stamped "Y" replaced it. When the cost of a ride rose to $1 in 1986, the "bull's eye" token, which featured a round center plug made from gray metal, was introduced. The last version of the token, with a cut-out pentagon, appeared with the $1.50 fare in 1995.

THEFT AND SPECULATION

|

|||

As the tokens gained in value, petty criminals devised ingenious if revolting ways to get them. Crooks jammed the coin slot to keep the tokens from falling down. As the commuter walked off indignantly -- out a token but unable to get through the gate -- the perpetrator would swoop in and suck the token out of the turnstile. The epidemic led to widespread disgust among even hardened New Yorkers, and to ingenuity among subway workers who fought back with mace, chili powder and even super-strength glue.

Fare increases also gave rise to a unique form of arbitrage. When a hike was announced, people would begin hoarding extra tokens, hoping that transit officials would continue to use the old ones, instead of going to the trouble of minting a new coin. Sometimes the subway riders were right and made a nice little profit.

This year, collectors and nostalgic New Yorkers began stocking up as soon as the token's demise was confirmed. Anticipating a run on the coins, New York City Transit limited sales to two per customer on March 30.

But, so far a massive investment in subway tokens seems unlikely to reap big payoffs. A couple of days after official sales ended, the last version of the token was selling on eBay www.ebay.com for between $1.99 and $14.50. Even the original token, the dime-sized 1953 version with the Y cutout, was drawing bids of no more than about $25.

SIXTY MILLION CUFFLINKS?

|

|||

What about all those tokens? Will they join keys for defunct locks, cigarette lighters and old scouting medals in the backs of thousands of dressers drawer across the city? Or will the financially ailing transit authority find some way to make gold from brass?

Transit officials are not sure. Of the 60 million tokens minted for the Transportation Authority in 1991, 41 million are in a vault somewhere in Queens. Transit officials will not say where, for security reasons.

If the past is any guide, most will end up in a furnace. "If they follow previous iterations of the token, they will be sold as scrap," said Charles Seaton, a spokesman for New York City Transit. He said the scrap dealers could sell some of the tokens to jewelers and souvenir makers, but New York City Transit will not get into the business of making cufflinks. About six million of the current tokens are already believed to be in the hands of collectors or are lost. The Roosevelt Island Tram bought 7,000.

Kilmartin Industries, the Attleboro, Mass, mint that sold the 1991 batch of tokens to the system for $7.6 million, doesn't have much interest in them. "It doesn't stir any emotions with me at all to be honest with you," Tom Vermillion, a sales manager at Kilmartin, told Newsday recently.

METROCARD HUT?

Now that the token is gone, straphangers face a new problem: What should they call the 700-plus structures formerly known as token booths?

|

|||

Officially, New York City Transit has rechristened them "station service booths," but that seems unlikely to catch on. Our recent brief but fruitful survey of subway riders yielded a variety of suggestions, among them: MetroCard sales booth, fare sales booth, good-for-nothing booth, little house of cards, metro mansion, MetroPod, ticket hut, kiosk, information booth, token booth ("because the person inside is usually the 'token' human around"), MetroCard Hut (or McHut, for short), no-use booth, card shack, hold-up target, "customer service center -- ha!," bullet-proof transportation hospitality center and "affordable housing."

Of course, people still "dial" push-button phones, so maybe New Yorkers, notorious creatures of habit, won't change at all. They will simply buy their MetroCards at a token booth.