The State’s $7 Billion MTA IOU Comes Due

(photo: the governor's office)

MTA officials acknowledged at their June 2019 board meetings that the agency is borrowing money to be repaid through a New York State law that promised to have the State of New York provide the MTA $7.3 billion once the authority had exhausted its own funds on spending for the current five-year capital program.

The 2016 state law was merely an “IOU," there had been no specific source of funds identified for how the state would pay the money, nor has there been any plan developed since enactment in the state budget that year.

The state's total commitment was $8.6 billion, including some new capital funds it added as part of the newer Subway Action Plan and other promises, which to date have provided about $1 billion in actual funds. It is the $7.3 billion IOU that is still outstanding. New York City was also required to provide $2.7 billion to the agency as part of a mutual obligation with the state. The city has provided about $800 million to date.

These commitments refer to the current 2015-2019 Capital Construction Program, not the 2020-2024 Program to be released in a few weeks by the MTA. That new program, not yet adopted, will have its main funding coming from the congestion pricing system passed earlier this year, with revenue from the tolls scheduled to begin in 2021.

The elements of the 2015-2019 MTA Capital Program were patched together in the 2016-2017 state budget (a year late), my final year in the State Assembly while I was still chair of the Assembly Committee on Corporations, Authorities, and Commissions. The full 2016 package that became the Capital Program was about $30 billion; some $3 billion has been added since I retired. The MTA Capital Program Review Board adopted the plan in 2016 shortly after the budget was enacted.

The question of the state’s outstanding commitment to the MTA capital program, written into the law as the last dollars to be spent in the overall plan, has been the source of limited scrutiny, but is now in the spotlight as the IOU comes due and the next capital program is designed.

At the June 26 public meeting of the MTA Board Finance Committee, finance chair Larry Schwartz and board member Veronica Vanterpool expressed concerns about an agenda item authorizing the MTA to borrow an extra $2 billion to fund the capital program.

Per the minutes of that MTA Finance Committee meeting (page 12):

"Ms. Vanterpool voiced her reservations about increasing the amount, noting that there is that $7.3 billion commitment from the State that has not been received, as well as the commitment from the City. Mr. Foran [the MTA's Chief Financial Officer]... noted that the commitment from the State is predicated on MTA to spend MTA dollars first and that MTA is already beginning to commit against the State's portion (about $2 billion commitment, with some expenditures already incurred) and the State has agreed to that.”

The discussion continued (page 13), "Mr. McCoy [MTA Finance Director] commented that regarding the State funding, the $1.2 billion in BANs [bond anticipation notes] were issued in two components; $1 billion for MTA funded projects, and $200 million is designated for the projects under the State Commitment. Mr. McCoy stated that it was clearly communicated with the State that, when the notes are due, the State will need to provide the funding."

The MTA Board proceeded to add the $2 billion in new borrowing at its main June 26 board meeting two days after this finance committee discussion. State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, in an August 7 report on New York City's financial condition, stated (on page 34), "According to the MTA, it has committed all of its capital resources and has begun to commit up to $3 billion against the State's obligation. Consequently, the MTA will require funding from the State beginning next State fiscal year (2020-21) to cover the cash cost of these capital commitments"

Where Will The Money Come From?

The question now is: How will the state meet this new commitment in the coming budget?

The state has the option of itself providing the MTA the money directly, or creating a stream of funding for the MTA to enable the agency to secure the borrowing of the funds, or some combination thereof. But there are serious challenges, the first of which is that 2020 is an election year for the state Legislature.

To enable the MTA to borrow $7.3 billion, a revenue source, i.e. another tax, would need to provide the authority about another $400 million a year. Does the Legislature want to do another tax increase in an election year? Maybe 2021, not 2020. Seven of the eight new Democratic State Senators that won the Democratic party the majority come from the New York City suburbs. Four of these seven suburban races were super-close, with the Democrats winning by just 2-3 percentage points, or even less.

Several other races were won by less than ten points. Many of these newly-minted legislators could be uncomfortable voting for another tax increase for the unpopular MTA, after voting this year for congestion pricing, a real estate transfer tax surcharge, and internet sales taxes. They are already likely to face Republican attacks in the election for these votes.

The state's ability to borrow the funds directly (the MTA does not need all $7.3 billion next year, but over several years) is also severely constrained by limits on the state government established by the Debt Reform Act of 2000. This law limits state-supported debt to 4% of the state's total personal income from the preceding calendar year. The following chart from a July 2 state comptroller report on the 2019-2020 budget shows how the state's capacity to borrow is dwindling.

Next year the state's ability to borrow funds in support of the entire state budget and the entire capital program will be limited to about $1.36 billion and by 2023-24 will be nonexistent. Borrowing for the MTA would be competing with roads and bridges, water and sewer, the state and city public university systems, mental hygiene, and the environment. Little could be anticipated from this source given the constraints.

Another possibility would be for the state to provide the MTA money from the financial industry settlement windfall. Some $2.6 billion is available in 2020-21 from this source, but, once again, the MTA would be competing with upstate economic development commitments, Javits Center and transportation commitments, and general budget relief. But Governor Cuomo and the Legislature could make several hundred million dollars available from this source -- once again, very limited, given the competition for other funds.

Of course, the Legislature could do a tax/fee hike in 2021, even something as simple as extending the for-hire vehicle surcharge on Uber and Lyft to trips with outer borough destinations or adding to the Manhattan business district price. But it is a tax increase of sorts.

Late in the 2015 legislative session, as we struggled to deal with funding the 2015-2019 MTA Capital Program, I worked with MTA senior officials to introduce legislation to provide the MTA a new source of money without a tax increase. The bill provided for a staggered diversion of existing personal income tax revenue from the MTA region over a four-year period to enable the MTA to borrow what was viewed then as $6-7 billion, providing about $400 million a year in revenue to which the agency would be entitled at the end of four years.

Growth in the state's personal income tax revenue would now bring in about $500 million a year under the formula in the bill (A. 8227-a from the 2015-2016 session), so the percentage amount in the old bill could be shaved.

The critical concept of the bill was that it statutorily entitled the MTA to the revenue, enabling it to borrow the money itself and not be a debt of the state subject to the Debt Reform Act and the limits on the state’s capacity to borrow. As written, it would start in the first year with a small three-tenths of one-percent diversion of PIT revenue in the region to the MTA , reaching 1.2% in the fourth year. Each year's revenue piece was separated in a schedule pursuant to law, so if a recession hit, the state could suspend the following year's diversion and preserve revenue in the general fund.

The governor and the Legislature should continue to examine this concept, which was believed to be workable by MTA officials at the time, though viewed by senior Assembly Ways and Means staff as just not needed. But the $7 billion IOU has come due.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Planned Massive New Jail Will Spark Chinatown Health Crisis

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office)

“Life in the fairest big city in America should never feel impossible,” said Mayor Bill de Blasio, touting his agenda for the coming year during his annual State of the City speech this past January.

But just a few blocks from where de Blasio works every day at City Hall, a health crisis brought on by the mayor’s own jails proposal could soon make life increasingly unfair, unhealthy – and yes, impossible – for tens of thousands of New Yorkers who reside in Chinatown.

The de Blasio administration unveiled plans to build four borough-based jails in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan as a part of his administration’s continued effort to close Rikers Island jails – a 10-year, $10 billion undertaking that is going through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) and is headed for a vote by the City Planning Commission on September 3.

As that debate continues, newly submitted testimony by the NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health regarding the proposed Manhattan jail at 125 White Street states that construction of the planned 450-foot jail (see city rendering, left) will have detrimental health-related consequences for those residing in Chinatown – especially for vulnerable senior citizens.

As that debate continues, newly submitted testimony by the NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health regarding the proposed Manhattan jail at 125 White Street states that construction of the planned 450-foot jail (see city rendering, left) will have detrimental health-related consequences for those residing in Chinatown – especially for vulnerable senior citizens.

That is why members of the City Planning Commission must reject the mayor’s jail plan and demand it be reworked to prioritize the health and safety of Chinatown residents. And if the City Planning Commission fails to take that crucial step, the City Council must step up and say no to this deeply problematic proposal.

The NYU testimony demonstrates that the rubber-stamped Environmental Impact Study commissioned by the city as part of the ULURP process was incomplete and didn't tell local residents the full story. As long as the mayor refuses to acknowledge its shortcomings, he shouldn't be allowed to build the new facility.

To be clear, this isn’t about NIMBY politics – and isn’t the first time Chinatown has had to deal with the repercussions of demolition- and construction-generated pollutants. Following the September 11 attacks, the EPA conducted an evaluation to determine how construction-site emissions affected nearby residents’ health in the short and long term. The findings are disturbing.

The EPA concluded that increased exposure to elevated fields of pollution from construction sites worsen residents’ co-morbidities and often result in hospitalizations and acute disease episodes.

The EPA report cites an immediate increase in respiratory ailment-related hospital admissions following the attacks, and an increase in admissions for heart- and stroke-related problems as well. The EPA indicated that Chinatown’s asthma rates are twice that of other New York City communities, and those exposed to the surrounding air pollutants were found at higher risk of having respiratory and cardiovascular issues.

And when it comes to the new jail proposal, expected construction-site emissions, otherwise known as particulate matter (PM), have both short- and long-term repercussions, according to the NYU testimony. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that PM pollution causes 8 percent of all lung cancer deaths, 5 percent of cardiopulmonary deaths, and 3 percent of respiratory-infection deaths.

The City Planning Commission should also be concerned that Asian-Americans are increasingly sensitive to construction-site emissions, per NYU’s testimony. Chinese, Korean, and South Asian neighborhood residents have a higher risk of getting cancer than non-Hispanic whites when exposed to PM, and the mayor’s decade-long proposal would see Chinatown engulfed in PM for the foreseeable future.

The bottom line is that de Blasio’s proposal will essentially make parts of Chinatown uninhabitable for years. Those living in adjacent buildings may be required to relocate, and those living in Chinatown will be forced to deal with a consistent stream of construction-site emissions that will undeniably put their health and the health of their families at serious risk.

Members of the City Planning Commission and the City Council have a lawful responsibility to ensure that any new development plans do not harm the public interest – and they must do that by rejecting de Blasio’s jail plan. There’s just no reason why the necessary and sensible effort to close Rikers jails must come at the expense of the health of local communities.

***

Jan Lee is Chair of The Chinatown Core Block Association. Eric Dillenberger is Chair of the Walker Street Block Association.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Addressing the Growing Problem of Senior Homelessness

(photo: WSFSSH)

The conversation around affordable housing in New York largely focuses on ensuring that working people can continue to live here.

Bus drivers, healthcare workers, elementary school teachers -- too few of the people who fulfill some of our city’s key services can afford a market-rate one-bedroom apartment within city limits. It’s inarguably a crisis that threatens the fundamental quality of our city, as well as its continued economic growth.

But another tidal wave is growing that deserves equal attention: as baby boomers retire and reach old age, a growing number of seniors -- on fixed incomes, many of them with ongoing health care needs -- are finding themselves homeless.

The population of single adults 65-and-older living in shelters has doubled since January 2014 to over 1,400 people. A UPenn study estimated that this population could grow to nearly 7,000 by 2030.

Homelessness hits seniors particularly hard: without a permanent address, it becomes harder to secure necessary medications, and the likelihood of senior abuse rises significantly. Social isolation has cascading impacts on emotional and physical wellbeing.

Homelessness increases an individual’s risk of mortality, and homeless individuals 50- to 62-years-old often have healthcare needs more likely in later age -- like problems with vision, mobility, and hearing, as well as falls.

How we address this crisis gets at the heart of who we are as a city.

The Mayor’s Office and City Council have made some inroads in building affordable housing for independent, low-income seniors, with over 989 units built to date during the de Blasio administration and another 2,986 in the pipeline, which will expand to roughly 5,000 units -- but homeless seniors have very specific support needs, and more can be done to develop and operate permanent affordable supportive housing catered to them.

A 320-unit, three-building affordable senior housing campus known as Tres Puentes/Borinquen Court, which opened at the end of May and is operated by long-time supportive housing developer the West Side Federation of Senior and Supportive Housing (WSFSSH), which I run, may provide a model.

Diverse groups in the South Bronx worked together to ensure the successful navigation of some of the city’s most complex urban development challenges in service of the project, which, now that it’s open, not only provides top-tier services for seniors, but does so in a space that the neighborhood can be proud of.

Here’s three key lessons we’ve learned through the development and operation of this campus that may be replicable for other senior housing in the Bronx and across the city:

First, for successful development, create strong local partnerships.

It’s an unfortunate reality of our city that residential communities can be suspicious of new affordable housing. By bringing everyone to the table from day one, from residents to developers, community members and government, you can build a coalition to support new development in service of area seniors. You can address fears before they become real roadblocks to bringing needed housing online.

Strong coalitions are also more likely to successfully troubleshoot some of New York’s most vexing challenges on the road to development -- like overcoming infrastructural surprises that are the result of historic disinvestment and comprehensively addressing environmental remediation needs.

Second, embrace bold design choices.

Shirking the institutional aesthetic to weave in design elements practiced more traditionally in market-rate residential projects typically reserved for individuals of higher socioeconomic status has multiple benefits -- from adding architectural diversity into the neighborhood to showcasing to residents that their comfort matters.

Bright colors and double-height ceilings make the space cheerful and welcoming, a place for seniors to feel elevated and connected to their community. The building is adorned with a corrugated veneer popular in modern design, evoking the neighborhood’s industrial past and creating an inviting façade.

Aesthetics matter, not just to residents and staff, but to the neighbors who pass the site every day. Thoughtful aesthetics are a reminder that affordable housing can be an integral part of our communities, that its residents are our neighbors, worthy of identifying with and fighting for.

Third, invest in unique social services for seniors.

Housing homeless seniors is a start; but to help truly end the homelessness crisis among seniors, comprehensive social services that get at the unique needs of the age group are a must. These social needs can only be addressed in supportive housing, of which there is so little.

Every angle of seniors’ social needs must be addressed as part of any new supportive housing development.

Financial coaching can not only prevent abuse and scams, but help navigate local and national systems for health care and entitlements.

Exercise regimens should be catered to the age group, focusing on muscle retention and flexibility as well as other medically-indicated activities.

On-staff social workers and partner health providers must specialize in senior issues like dementia and depression, and complex social challenges with adult children and friends.

But it’s not just addressing crisis; with proper support, today’s seniors can live fuller, longer lives. By investing in smart development to address seniors’ needs, we can ensure that they live lives more connected to their communities.

With a commitment to high-quality housing New York can lead the way in empathetic and thoughtful care for seniors, solving its senior housing crisis for good.

***

Paul Freitag is Executive Director of West Side Federation for Senior and Supportive Housing (WSFSSH).

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Depraved Indifference and Second Look Sentencing

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Valerie Gaiter died in Bedford Hills Correctional Facility last week. She had been in prison longer than any woman in New York State. She had cancer. She was 61 and had served 40 years of a 50-years-to-life sentence for her conviction of the murder of two elderly people in Brooklyn in 1979. She was eligible to see the Parole Board in 2029 when she would have been 71.

Edgardo Gonzalez is in Fishkill Correctional Facility. He is 75. He has chronic liver failure, hepatitis, and other ailments. He has lost almost 40 pounds in the last four months. He has served 36 years of a 50-years-to-life sentence for his conviction of the murder of two people in a Brooklyn social club in 1983. He will be eligible to see the Parole Board in 2034 when he would be 90 years old.

To be perfectly clear, Ms. Gaiter and Mr. Gonzalez were convicted of brutal crimes. Lives were taken. Families were devastated. The harm caused is incalculable.

And yet, how much time must someone serve for a violent crime? This question must be confronted to redress the crisis of mass incarceration, since the vast majority of the 2.3 million people in United States jails and prisons were not convicted of so-called low-level, non-violent offenses.

As long as people are defined as “violent criminals” it becomes easy to banish them forever and talk about the crisis of mass incarceration but do nothing to end it. Those serving life sentences are more than the crimes they committed. It is time to interrogate whether those who promoted get tough on crime policies continue to perpetrate their own violence by ensuring that older, reformed offenders die in prison.

Mr. Gonzalez has a stellar institutional record and extensive family support. He presents no threat to public safety. He’s received only one disciplinary ticket in 36 years and that was for having an untidy cell (a photograph of his mother taped to the wall). My students submitted a clemency application on his behalf two years ago but have yet to receive any response.

I met with Mr. Gonzalez last week at the Regional Medical Unit at Fishkill prison. Not that long ago, he was a robust former boxer in excellent health. He once fought future Olympic gold medalist Howard Davis in Madison Square Garden. Pictures of that match showing a chiseled athlete in the prime of his career were part of his clemency application. Now his health is in rapid decline. He is confined to a wheelchair and struggles to breathe. His voice is barely a whisper.

Mr. Gonzalez asked what the law meant by “depraved indifference.” In 1983, he was inside a social club when a melee broke out. Mr. Gonzalez was shot through the stomach, but also shot and killed his assailant. For that, he was convicted of intentional murder. Another shot fired by Mr. Gonzalez killed a woman standing nearby. For that, he was convicted of what the law calls depraved indifference murder.

As we discussed the law regarding depraved indifference murder, it was impossible not to think about how the state treated Valerie Gaiter, Edgardo Gonzalez, and the thousands of others serving death by incarceration sentences.

The law says you are guilty of depraved indifference murder if you engage in conduct that creates a grave risk of death and are aware of and consciously disregard that risk. We know the grave risk, indeed the likelihood, of death in prison for people serving life sentences. According to a report by New York’s Department of Corrections, the average age of death for those who died in state prison of natural causes was 57. And yet, that risk is regularly disregarded as sentences like those imposed on Valerie Gaiter and Edgardo Gonzalez are often sought by prosecutors and imposed by judges.

The courts further define a depraved indifference state of mind as exhibiting an utter disregard for the value of human life; simply not caring whether grievous harm will result. Depraved indifference is said to reflect conduct that is wanton, deficient in a moral sense of concern, devoid of regard for the lives of others.

It is wanton, morally deficient and utterly devoid of regard for the value of human life to preclude the potential for redemption; to ignore all those who have long since aged out of any threat of future crime, especially those who are living out their final days in prison medical units.

We must take steps to ensure that the state no longer acts with depravity toward those in prison.

Sentencing laws must be reformed to bring the United States in line with other industrialized nations where a 20-year maximum is the norm. Prosecutors and judges must stop the common practice of seeking and imposing maximum sentences on those who exercise their constitutional right to a trial.

But the most far-reaching fix is the one proposed by the American Law Institute’s revisions to the venerable Model Penal Code – second look sentencing.

The Code urges state legislatures to enact a “second look” provision; to create a mechanism to reexamine a person’s sentence after 15 years no matter the crime of conviction or the original sentence. It is not a “get out of jail free” card. Release must be earned. It must be evident that the person is not a threat to public safety and there must be evidence of rehabilitation; proof that the person has changed, come to grips with, accepts and acknowledges their actions and the harm they caused.

The Code recognizes that a sentence once imposed is not just, fair, and appropriate in perpetuity. Second-look mechanisms are meant to recognize the possibility of transformation and allow for mid-course correction if warranted by changed circumstances -- major changes in the offender, the crime victim, or the community. It is consistent with the growth of restorative justice that eschews punishment paradigm of the last several decades and is also a way to confront the systemic racism revealed in arrest and sentencing disparities.

Such a bill was introduced in the last New York legislative session regarding parole eligibility for people who are least 55-years-old and have served at least 15 years. There will be costs associated with establishing such second-look processes, but money will ultimately be saved as more people are sent home from prison. Most importantly, basic human decency should compel a different result for Valerie Gaiter and the many others facing the prospect of dying behind bars.

In the meantime, we must use the limited procedures available to ensure a measure of dignity to those at risk of perishing in prison. New York does have a mechanism in place for compassionate release for those with terminal illness. However, according to a study by the Vera Institute of Justice, there were 476 requests for compassionate release from 2013-17, but only 72 people were ultimately released. On the other hand, 143 of those medical parole applicants died in custody, demonstrating why other, more comprehensive, solutions are necessary.

Edgardo Gonzalez was recently certified by corrections medical personnel as one of the few people eligible for medical parole. He had his medical parole interview before the Parole Board last week. To deny him parole would be the height of depraved indifference.

***

Steven Zeidman is a professor of law at CUNY School of Law and a former Public Defender. On Twitter @SteveZeidman.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Seeing Healthcare Through a New Lens

(photo: @sunyopt)

Most people have heard the saying that the eye is the window to the soul. But what they may not know is that the eyes also hold the key to revealing underlying health issues for many individuals.

As optometrists, we recognize that making eye exams accessible to underserved families can be a critical first step in addressing healthcare disparities in New York City. And as healthcare providers, we’re always looking for new ways to educate patients about the importance of preventative care as a first step in detecting chronic, systemic health issues and ultimately to enhance population health.

Brownsville and Battery Park are just nine miles apart, but life expectancies of their residents are more than ten years apart. Something as simple as an eye exam can help fix that. That’s why, three years ago, SUNY Optometry created the Health and Wellness Expo to bridge the gap between the most-vulnerable members of our society and healthcare professionals. By offering free screenings for vision, dental care, podiatry, as well as access to cholesterol, Body Mass Index, and diabetes testing, community members can engage with health professionals and start taking control of their wellbeing.

An eye exam is never just an eye exam. A routine eye exam offers far more than simply testing eye and visual health. It provides insights into the future health of a patient and reveals opportunities to enhance quality of life.

Eye examinations are especially critical for the pediatric population because good vision is crucial to children’s cognitive development. However, children from underserved and underrepresented communities often lack access to eye examinations based on perceived barriers – frequently, a result of financial challenges within the family.

The Expo, which was initially billed as a back-to-school event three years ago, and with less than 500 participants, has evolved into one of our most important community outreach initiatives. At our most recent Expo on August 3, we welcomed nearly 1,000 New Yorkers who had a chance to interact with health professionals and community-based organizations.

We know that race, ethnicity, and economic hardship are contributors to healthcare disparity, and it not only impacts the affected group but our entire community.

By connecting families to community health organizations from all over the city, we are working to ensure that no particular group remains marginalized.

The facts are troubling: Approximately 60 percent of children with learning difficulties have a form of undetected vision impairment. Twenty-five percent of school-aged children have an eye problem that limits vision. More than 60 percent of parents don’t include eye exams as part of their children’s healthcare routine.

Determined to ensure that financial barriers do not become an impediment to healthcare access, we formed critical partnerships with community organizations across all five boroughs.

By offering free vision screening alongside other health services providers, children and their families now have access to additional healthcare services and educational resources. More importantly, we are helping to eliminate one of the barriers that often translate into academic challenges for children.

When people think about healthcare, they often do not immediately think of optometry or the impact that eye care has on overall wellbeing. Nor do they realize that a simple eye exam can be a window to uncovering other chronic diseases. We know that eye health is critical, particularly among low-income communities and communities of color where rates of diabetes are high, leading to loss of eyesight.

As the only institution in New York State that educates Doctors of Optometry, we owe it to our communities to improve the health of our population through better eye care.

We understand the challenges that thousands of families in New York are experiencing. We know this because, across our clinical care system, we encounter nearly 250,000 patient visits annually, in addition to training the next generation of leaders and scholars in eye care, education, and research. One out of every two optometrists in New York are graduates of the SUNY College of Optometry. We must do all we can to prepare the next generation of healthcare providers to care about the communities they serve.

***

Dr. David A. Heath has served as president of the State University of New York College of Optometry since June 2007. He is the third president of SUNY Optometry, which was founded in 1971 and is one of the 64 campuses constituting the State of New York’s public university system. On Twitter @SUNYOPT.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Replacing Unsuccessful ‘Community Benefits Agreements’ with Neighborhood Stock Ownership Plans

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

When Jeff Bezos, the world’s wealthiest man, and Amazon sought to locate a major campus in New York City, they ran into a buzzsaw of opposition that derailed the project. Despite the promise of tens of thousands of jobs and millions of dollars in local investments, members of the community reacted to the company’s planned arrival with fear and fire. Rallies against the tech giant occurred weekly. Elected officials orchestrated public hearings where they criticized the corporation. Lots of bad press accompanied the news that Bezos would have his own helipad.

Neither Governor Cuomo nor Mayor de Blasio could put this Humpty Dumpty deal together again. After months of disgrace, Amazon withdrew.

Now, the world’s third-wealthiest man, Mansour bin Zayed, owner of the New York City Football Club, wants to build a soccer stadium in The Bronx. And, like Bezos in Queens, he’s likely to run into a storm of opposition from that community. What can be learned from the Amazon issue that can help both the neighborhood and the stadium project?

The collapse of the Amazon move into Long Island City signaled the end of the era of the “Community Benefits Agreement” (CBA). The benefits agreement strategy has been used by neighborhoods for decades to confront gargantuan development projects like sports arenas or corporate expansions. But decades of unfulfilled promises made by corporations and government officials to communities have sullied the reputation of CBAs. New York City neighborhoods have become suspicious of agreements that can be (and have been) ignored by behemoths like Amazon, Forest City Ratner, and politicians.

The Barclays Center was created with a CBA. The new Yankee Stadium came with a CBA. And, the current talk about a Bronx professional soccer stadium includes conversations focused on perks promised to the host neighborhood, like jobs and housing for local residents. But the promise of perks never convinced Queens that the Amazonian tech giant and the world’s wealthiest man were worthy of their support.

Civic groups in Queens like those in the Bronx and Brooklyn have become disillusioned because these benefits agreements lack enforcement. At Yankee Stadium, members of the community board who opposed the new ballpark and its CBAs were removed from the board. In Brooklyn, small businesses feel ripped off by the developer whose community benefits promises lacked the force of law and transparency. In Queens, local elected officials were left out of the negotiations by the mayor and the governor.

New York City neighborhoods need a new strategy to safeguard their integrity and create a partnership among residents, local businesses, nonprofits, government, and developers.

I propose a new approach, a Neighborhood Stock Ownership Plan (NSOP), modelled after employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs).

ESOPs have been around since 1956. Across the country, there are nearly 7,000 ESOP companies covering more than 14 million participants. In ESOPs the workers earn the right to buy shares in the company at a discount rate based on the number of years they have worked there. These worker-shareholders have a seat on the company’s board. Profits are shared with employees through dividends and increases in the stock price. Transparency abounds, and so does workplace satisfaction.

The ESOP model can be modified to reflect and reinforce lots of different stakeholders, not just employees. It can become a mechanism by which residents, local businesses, employees, and civic organizations become partners with, not opponents of, a developer.

This is how a Neighborhood Stock Ownership Plan could work: those who live, work, or own a business in the development area will be given stock options based on the length of time they’ve lived, worked, or operated a business in the project district. Nonprofits in the vicinity would also be gifted shares based on their membership. Instead of agitating, NSOP members will be aggregating money, based on the revenues of the company and its stock price.

This NSOP will protect communities from having to settle for corporate hand-outs. It will tie the community and the corporation together so that revenue for the company automatically means money for the community.

If a soccer stadium were built in the Bronx, for example, an NSOP would mean that broadcast fees, stadium naming rights, and merchandising deals benefit those whose transportation, trash, and tranquility will be impacted by the sports venue. Using an NSOP framework would give neighbors and newcomers a common ground to discuss corporate policies and procedures. With an NSOP, the dynamics of patron and patronage that created hostile environments for Amazon, Barclays, and likely a new soccer stadium could be avoided.

Whatever is good for the community will be good for the corporation and vice versa.

Will the stadium developer, the team owners, the mayor and the governor have the foresight to reject the old “community benefits” strategy and try a new approach? Will they see the soccer stadium project as a chance for social innovation and community support? Seems to me like a good goal (pun intended) for everyone.

***

Dr. Cary Goodman is executive director of the 161st Street Business Improvement District at Yankee Stadium.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Small Business ‘Crisis’ That Isn’t

(photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

When shops and restaurants that you love and depend on close it can be heartbreaking; I know from personal experience. My Upper West Side neighborhood has been seen as the epicenter of what some call a “small business crisis” in New York City, and we have certainly seen our share of lost community icons and long-shuttered storefronts, but a new report shows there is no citywide crisis and lawmakers should be very careful as they consider remedies to what problems do exist.

Earlier this month the New York City Department of City Planning issued a comprehensive, well-designed study of vacancies on commercial business strips in 24 neighborhoods across the city. It shows that retail storefront vacancies are not unusually high in most neighborhoods (the industry standard is 5-10%) and, where they do exist, are due to a number of causes, which differ from place to place and storefront to storefront.

Just last month, a package of bills was adopted by the City Council that will provide even more information about retail vacancies by requiring that landlords report periodically to the Department of Finance on the number and status of their retail spaces.

Yet elected officials continue to refer to a “crisis” of retail vacancies. Just a few days after the City Planning report was released, Council Speaker Corey Johnson bemoaned the “blight” of retail vacancies “all across the city.”

Examples of long-standing merchants priced out by rising rents are more compelling news stories than data that shows the localized nature of the problem. So, despite the fact there is no citywide crisis and the Council’s new legislation will provide additional data on vacant storefronts, support is strong for a proposal to require sweeping protections for retail tenants to help assure lease renewals, including mandatory 10-year terms and arbitration when landlord and tenant cannot agree on rent increases. The number of Council sponsors of the “Small Business Justice and Stability Act” (SBJSA) has grown to 30 (of 51 members) since a hearing was held on it this past December.

Concern about retail storefront vacancies and turnover in New York City is not new. It has been labeled as a “crisis” as far back as the 1970s and was a focus of intense scrutiny during the Koch administration in the mid-’80s when the mayor responded by forming a commission to study the topic. Then-Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger championed a rent arbitration proposal back then.

Several of my favorite restaurants, diners, and clothing stores on the three blocks of Amsterdam closest to my apartment have closed over the last ten years. There are many vacancies in my neighborhood for a number of reasons.

Some are due to the creation of new, unrented retail space on the ground floor of brand new high-end residential buildings that have sprouted up along the corridors; some are because proprietors decided to retire, or because a new enterprise misjudged how much business it would attract in the area, or because the landlord -- sometimes a residential rental or co-op building -- is holding out for a chain store type of tenant that can pay a high rent to help offset increasing costs like property taxes. This is all part of life in an upscale neighborhood like the Upper West Side. It may be unsettling and even sad, but it is not a crisis.

Also, while some of us may miss our favorite places, the new stores and restaurants that replace them are serving the people that live here, albeit in different ways.

An example is a large new restaurant/juice bar that has opened around the corner from my apartment. A beloved diner used to be there, and when the lease was not renewed nine years ago, it remained vacant for more than two years. The two small stores next to it were also vacated, while the rental apartment building owner held out for a larger tenant to take over the entire space. A slick new place arrived that lasted five years but didn’t seem to me to have been able to generate enough business to sustain the large space. (There were protests when the spaces were combined and when the new restaurant opened.) After another six months, Tacombi, which has several other branches in the city, opened. With a menu of reasonably-priced Latin-American food and drinks it appears to be thriving and is filled with neighborhood families.

It is understandable that elected officials feel compelled to “do something” when their constituents feel impacted in such a direct and personal way, which explains why my City Council representative, Helen Rosenthal, along with Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, are two of the most vocal advocates for the SBJSA. But as the City Planning report shows, there is simply no basis for citywide legislation. Time will tell, but I expect that the newly-mandated reports from landlords will bear out that conclusion.

Moreover, the SBJSA will do nothing to bring back beloved stores that have already closed and could make it even harder to bring in new tenants since landlords, with less flexibility to respond to the market, will be more selective and want only those with a proven record of financial viability.

A more targeted approach would focus on strengthening retail storefront presence in those areas that City Planning calls “Underperforming Corridors” – in Coney Island, Brownsville, Richmond Hill, and Longwood -- which suffer from long-term historic disinvestment. Incentives and/or modest tenant protections would help these areas without interfering with business decisions in high-income areas that don’t need help.

We are not suffering from a shortage of places to shop or eat on the Upper West Side. The market will work here: if stores remain vacant for too long, landlords will lower the rents. That appears to be starting to happen.

The Council should not forge ahead with sweeping legislation that will impose real burdens on landlords in the majority of neighborhoods.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

State Campaign Finance Commission is About to Get to Work; Here’s How It Can Help Albany Clean Up Its Act

(photo: governor's office)

Over the next few months, New York State is poised to overhaul its campaign finance laws in ways that will help reduce corruption and pay-to-play and give more of a voice to the average person.

The potential for this major reform hinges on the actions of the Public Financing and Elections Commission. It is no exaggeration to say that the commission can achieve historic change when it issues binding recommendations on December 1.

The Commission was established during the April budget deal following a campaign for public financing by the 200-group coalition Fair Elections for New York, including Reinvent Albany. The nine-member state commission was appointed by Governor Cuomo and legislative leaders, and is charged with establishing a public financing program.

We want the commission to create a strong small-donor matching program, dramatically lower campaign contribution limits, and establish independent enforcement as in New York City’s successful program, which is widely seen as a national model.

A public financing system encourages everyday New Yorkers to participate in our democracy by matching small contributions (or a small portion of a contribution) with public funds. This amplifies the voice of regular folks who cannot make large contributions, and often aren’t even asked for donations.

Reinvent Albany found the state’s legislative leaders raised few campaign donations from the very people they were elected to represent during the 2018 election cycle. State Senate leaders raised only 23 percent of their contributions from their home district residents, while Assembly leadership raised just 16 percent.

Public financing is essential for fixing our broken campaign finance system. Most of the money donated to Albany elected officials comes from special interests – corporations, associations, and unions – and very wealthy individuals. The 2013 Moreland Commission found the Assembly Health and Senate Committee Chairs in 2011-2012 received about three quarters of their campaign contributions from lobbyists or the healthcare and insurance industries. Candidates received 65% of their funds from donors who gave $1,000 or more and just 3% from donations of under $100 during the same period.

If this year’s commission truly wants to change Albany, it must establish a strong public financing system. Reinvent Albany has put forth 18 recommendations for a strong public financing program, including these critical components:

-Create an independent agency to administer campaign finance for all candidates, including those who take public funds. With the state giving public funds for campaigns, the enforcement agency must be fair, independent, and safeguard taxpayer funds so they are used appropriately.

-Dramatically lower contributions limits – and make even lower limits on doing business donors – for all candidates. Candidates must be incentivized to participate in the voluntary public financing program rather than opt out and accept large donations. Donations to all candidates must be low enough so they do not create the appearance or reality of corruption or pay-to-play.

-Set reasonable thresholds to receive public funds. Candidates only receive public funds if they show community support measured by the number of small contributions and the dollar amount raised. These figures must be low enough so community members with local support can run for office.

-Match small contributions only. Only small contributions should be matched with public funds. A common misconception of the New York City public financing program is that candidates are given $6 in taxpayer funds for every $1 in small contributions up to $175. The truth is the first $175 of any contribution, no matter the size, is matched $6 to $1. Reinvent Albany believes taxpayers should not subsidize large contributions – currently allowed up to $70,000 – under New York State campaign finance law.

-Establish “sure winner” restrictions. To protect public dollars and the integrity of the public financing program, public funds should not be given in full to candidates with nominal opposition. Only a portion of public funds should go to candidates whose opponent has few endorsements, little media exposure, or hasn’t held an elected office previously.

If the Public Financing Commission includes these components in its program, and applies it to all offices and elections, New York’s campaign finance system will stand as a national model for addressing the problem of money in politics.

The commission and its appointers – the state’s leaders – should seize the moment for, at long last, transformative change.

***

Alex Camarda is Senior Policy Advisor at Reinvent Albany. On Twitter @alex_camarda & @ReinventAlbany.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York City Further Dominates State Job Growth; Rest of State Still Growing Slowly

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

New York City is now utterly dominating job growth in the State of New York. In the past two-and-a-half years, 79% of all new jobs in the state have been created in New York City.

New York State Labor Department seasonally-adjusted data show that 230,000 of the nearly 293,000 jobs created in the state from December 2016 to June 2019 were in the city. The growth rate in the city for the two-and-a-half year period was 2.1% per year; for the rest of the state separate from the city, the growth rate was about one-half of one percent per year*.

The city's share of growth has picked up even more since the end of 2017; 138,000 of the 169,000 jobs created statewide from December 2017 to June 2019 were created in the city -- nearly 82%. The city's share of total state employment was 46.5% at the end of 2016; as of June 2019 its share was 47.5%.

In October 2018 I wrote about the increasing contribution of the New York City economy to the state's tax revenue, much of it due to its share of employment growth. The increasing share of jobs will only accelerate this trend. While the city economy has become the engine of the state's economic growth, the Cuomo administration has focused much of its attention to rescuing the Upstate New York economy, which faltered in the two recessions that occurred after 2000.

|

NEW YORK EMPLOYMENT (000) |

||||||

|

Dec.2010 |

Dec.2016 |

June.2019 |

||||

|

New York State |

8587.4 |

9493.6 |

9786.2 |

|||

|

New York City |

3781.1 |

4413.6 |

4643.9 |

|||

|

Source: NY State Labor Department Seasonally Adjusted Employment |

||||||

Job growth rates for both New York City and the rest of the state have slowed compared to the period between December 2010 and December 2016. The city gained 633,000 jobs in that six-year period and its growth rate was 2.8% per year, compared to 2.1% per year since December 2016. The rest of the state gained 274,000 jobs in those six years, a growth rate of just under 1% per year. The city was 70% of the state's job growth in those six years, quite dominant then, but its share of growth just keeps expanding. Comparable national job growth rates for December 2010 to December 2016 was 1.9% per year, and 1.6% from December 2016 to June 2019.

One reason for slower growth outside the city is that job growth rates in the New York City suburbs have fallen to about the same rates of growth as Upstate. Upstate New York is a big area and one should not generalize too much about it. The growth rates in Upstate New York vary greatly by metropolitan area; some areas are achieving modest growth, others hardly any growth at all nine years after the Great Recession ended.

Long Island gained about 100,000 jobs from December 2010 to December 2016, but just 19,000 jobs in the past two-and-a-half years. The Orange-Rockland-Westchester metropolitan area gained 50,000 jobs in the 2010-2016 period, but just 7,000 from the end of 2016 to this June. These two New York City suburban areas had their growth rates slow from 1.3-1.4% per year from 2010-2016, to under six-tenths of one percent per year in the past two-and-a-half years.

One of their possible challenges may be the competition from New York City itself, since the city has become such a powerful economic and social magnet and these suburban areas are right nearby.

|

SUBURBAN EMPLOYMENT(000) |

|||||

|

Dec.2010 |

Dec.2016 |

June.2019 |

|||

|

Nassau-Suffolk |

1237.6 |

1338 |

1356.9 |

||

|

Orange-Rockland-Westchester |

663.7 |

713.9 |

724.3 |

||

The four larger Upstate metropolitan areas are growing. The Syracuse metropolitan area has gained more than 9,000 jobs in the past two-and-a-half years, growing at a rate of 1.2% per year. The Buffalo-Niagara Falls area has gained 10,500 jobs since December 2016, for a growth rate of three-fourths of one percent per year. From 2010 to 2016, it gained 20,000 jobs, for a growth rate of six-tenths of one percent per year.

The Rochester area gained 7,300 jobs in the past two-and-a-half years, a growth rate of .55 of one percent per year. From 2010 to 2016, it had gained about 23,000 jobs and had a growth rate of .8 of one percent a year. The Albany-Schenectady-Troy area gained 7,700 jobs since the end of 2016, for a growth rate of .7 of one percent a year. It had done better in the 2010-2016 period, gaining nearly 34,000 jobs in those six years for a growth rate of 1.3% per year.

|

UPSTATE LARGE METRO AREAS (000) |

|||||

|

Dec.2010 |

Dec.2016 |

June.2019 |

|||

|

Buffalo-Niagara Falls |

537.9 |

558 |

568.5 |

||

|

Rochester |

509.9 |

533.1 |

540.4 |

||

|

Albany-Schenectady-Troy |

432.7 |

466.5 |

474.2 |

||

|

Syracuse |

308.9 |

316.8 |

326.1 |

||

Several other Upstate metropolitan areas are growing at more than 1 percent a year. The Ithaca metro area had the best sustained growth since 2010 in Upstate New York, gaining more than 7,000 jobs, including 2,600 since the end of 2016, for a sustained growth rate for the eight-and-a-half years of about 1.5% per year. Two Hudson Valley areas, Dutchess-Putnam and Kingston, have gained about 5,700 jobs over the past two-and-a-half years for a growth rate of 1.1% per year. They have gained 13,000 jobs since December 2010.

Five smaller Upstate metro areas are struggling. Binghamton, Utica-Rome, and Elmira have gained 2,200 jobs among them since the end of 2016, for a combined growth rate of just three-tenths of one percent a year. Glens Falls metro has lost jobs since the end of 2016 and Watertown-Fort Drum has only gained 100 jobs in the past two-and-a-half years. The combined employment base of these five metropolitan areas is about 368,000, making them combined just barely larger than the Syracuse metro area and smaller than each of the four larger Upstate metro areas.

|

OTHER UPSTATE METRO AREAS(000) |

|||||

|

Dec.2010 |

Dec.2016 |

June.2019 |

|||

|

Dutchess-Putnam |

141.4 |

146.6 |

149.9 |

||

|

Utica-Rome |

129 |

127.6 |

128.6 |

||

|

Binghamton |

107.8 |

103.2 |

104.2 |

||

|

Ithaca |

59.1 |

63.9 |

66.5 |

||

|

Kingston |

59.8 |

61.9 |

64.4 |

||

|

Glens Falls |

54.5 |

56.2 |

55.5 |

||

|

Watertown-Ft.Drum |

42.9 |

42 |

42.1 |

||

|

Elmira |

39.5 |

36.8 |

37.2 |

||

The Labor Department's estimates for the 12 Upstate metropolitan areas show job gains of 45,000 since the end of 2016 to June 2019, with employment rising from 2.512 million to 2.557 million, or a growth rate of seven-tenths of one percent a year. The metropolitan areas of Upstate New York include about five-sixths of total employment in Upstate New York.

State Labor Department estimates for the non-metro areas of Upstate New York from 2016-2018 show job gains of a little over 4,000, for a growth rate of about four-tenths of one percent per year. The non-metro areas of Upstate New York have a little more than 500,000 jobs. They are one-sixth of Upstate New York employment and about 5% of total New York State employment.

The loss of population continues to be a challenge for sustaining economic growth in Upstate New York.

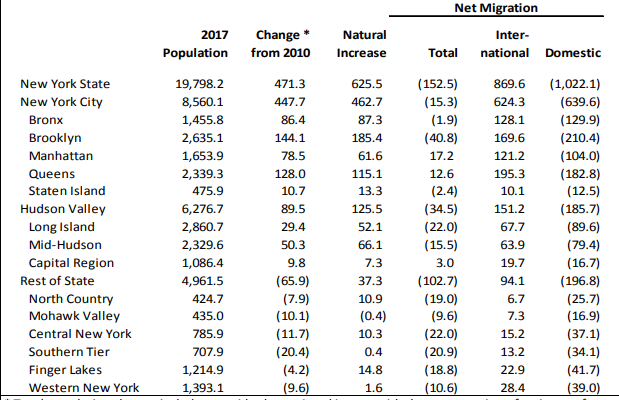

Below is a population growth table taken from the New York State Assembly's annual Economic and Revenue report from early 2019. It shows that New York City was 95% of the state's population growth between 2010 and 2017. The Hudson Valley, the Capital Region, and Long Island had small but positive population growth, but the rest of the Upstate New York regions lost population. Clearly these regions would benefit from new immigrants and increases in the allowable number of refugees into the United States.

And what of the Cuomo administration's efforts to help Upstate New York? The administration's main initiatives have included the Buffalo Billion, the $1.5 billion Upstate Revitalization Initiative, the Downtown Revitalization Initiative (some projects are in the Downstate area), the Albany Nanotechnology Initiative (begun during the Pataki administration), infrastructure spending in transportation and water and sewer upgrades, Tax-Free New York, cheap hydropower allocations from the State Power Authority, new investments in renewable technologies, especially windpower in the Lake Ontario area.

Surely these initiatives, and there are many, have had a positive impact, and are ongoing efforts that are budgeted for several years of future investment. But for them, the Upstate New York economy would likely be in even weaker condition.

Since the end of 2010, the aggregate numbers for Upstate show a net gain of 156,000 jobs. The state had a $10 billion deficit in 2011, the first year of the Cuomo administration, and there were spending cuts that affected state and local government employment, especially local schools.

Upstate New York lost 37,000 government jobs between 2010 and 2016, with those jobs stabilizing around 2013. Government jobs have remained relatively flat since that time in Upstate New York, so private sector employment is higher than the 156,000 net gain, probably about a 190,000 increase. It should also be noted that the State Labor Department's separate regional metro data show somewhat higher job growth numbers*.

The most recent year-over-year growth rates by state, from 2017 to 2018, showed 16 states had growth rates of seven-tenths of one percent per year, the Upstate New York growth rate, or less. Twenty-three states had growth rates of less than one percent. Upstate New York is not at the bottom of the nation in growth - it is slowly growing.

The state has also cut income, corporate, and property taxes, to the chagrin of progressives who would like to see stronger government spending. Governor Cuomo came into office in the aftermath of the Great Recession, and concern about whether New York taxes were undercutting business investment and encouraging out-migration affected early decision-making about how to grow the state's economy. More recently, recognition about the importance of infrastructure investment has replaced tax cuts as a priority, especially with the uncertain impact of federal tax reform on New York.

Since December 2010, the economy of the City of New York has essentially been carrying the state, with the city responsible for 863,000 of the 1.199 million jobs gained statewide.

(*The State Labor Department notes in its monthly employment press releases that the separate regional Metro area employment estimates do not match up (add up to the same numbers) as the aggregate employment numbers reported Statewide. The Statewide employment reports are estimated independently of the regional estimates. As a result there are discrepancies between subtracting New York City and its suburban areas from the statewide numbers to get the Upstate employment numbers, versus adding up each of the separate regional Upstate metro areas. Using aggregate numbers results in smaller employment growth totals for Upstate New York and the rest of the State outside New York City. The aggregate numbers show a growth rate of one-half of one percent a year; the regional numbers show .6-.7 tenths of one percent a year.)

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We’re Transforming Public Sector Contracting

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

As the City of New York continues to work towards building the most efficient, most transparent, highest functioning government possible, the historically opaque and wasteful government contract procurement process is often overlooked, and for too long has been deemed too complicated to untangle.

But new technology has the capacity to make government procurement simpler, faster, and cheaper -- and it is happening in New York.

Of the city’s $92+ billion annual budget, over 20% -- approximately $19.3 billion -- is spent buying the necessary goods and services used to provide vital services to New Yorkers, maintain and improve the city’s infrastructure, and facilitate the government’s day-to-day operations via nearly 40,000 financial transactions. For any large organization, from governments to Fortune 500 companies, managing that kind of scale is a challenge, requiring dedicated people and state-of-the-art software that is up to the task of making procurement as efficient as possible.

At Ivalua we have spent the last two decades building our spend management software to maximize value for both private and public sector organizations along every step of the procurement process, and we’re in the midst of doing it for the City of New York.

Spend management technology enables procurement and supply chain leaders to more effectively manage how their money is being spent by:

-Identifying opportunities to reduce costs and drive efficiencies;

-Improving transparency in bidding to ensure competitive pricing;

-Speeding up the contracting process;

-Streamlining the purchasing process for procurement officers and suppliers to ensure invoices match contracts.

Leading private sector companies have long leveraged such technology to optimize their procurement processes, maximizing value, improving efficiency, mitigating risk, and ensuring transparency for shareholders. Unfortunately, the ability of governments to drive similar results has been greatly limited until now.

Despite their best intentions, strict regulations and complex, ever-evolving legislation have bound the hands of those charged with procuring the goods and services needed to run a government. For decades, city agency procurement teams have had to rely on paper-based processes or homegrown, subpar solutions, without the best-of-breed capabilities that drive real value in the private sector. This frustrates everyone, from taxpayers who just want a park built, to the companies selling the playground equipment.

For years, Ivalua has been helping the most proactive public sector leaders close this gap at all levels of government, including states such as Maryland, Arizona, and Ohio, Shared Services Canada, Paris’ airports, and now right here in the great City of New York. With a major office right here in Manhattan (one of 15 around the globe), we live here and rely on the same vital services.

For New York, we’re now implementing a complete suite to maximize the efficiency and transparency of city government.

The city planned its transformation over three phases spanning several years due to the massive complexity involved. The first phase focused on vendor management and deployed in 2017. A vendor registration process that used to require 12 pounds of paper per vendor and take most vendors 30 days has been fully digitized and cut to just a day.

Information that was previously siloed at dozens of agencies is now shared, improving transparency and efficiency, with input already provided by over 12,000 contractors, 24,000 members of their staffs, and 7,000 city agency staff. Contracts can now be registered more quickly with more timely, automated submission to the city Comptroller.

The second phase deployed more recently and focused on streamlining the purchasing process itself. The third phase will address the bid solicitation and invoicing processes to take taxpayer dollars further while improving payment timeliness and accuracy. It is in design mode, on schedule to be delivered in 2020.

All told, New York City has already significantly improved efficiency, transparency, and the ability to deliver better services more rapidly. While much work remains, the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services has taken an incredible step forward that will prove to be a model for cities across the country, and we are proud to be leading the way with them.

***

Dan Amzallag is CEO of Ivalua, Inc. On Twitter @ivalua.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Attorney General James Should Sue to Dissolve the Trump Organization

NY AG Letitia James (photo: @NewYorkStateAG)

For a company of only a few dozen employees, the Trump Organization has accumulated an astonishing rap sheet of fraud, crime, and other corporate misconduct over the years. And since its owner came to occupy the Oval Office, the company has sunk to new depths as a vehicle for influence and corruption by supplicants from corporate lobbies and foreign governments.

Now that federal prosecutors have refused to pursue a clear case of felony campaign violations using the Trump Organization as the fraudulent financial vehicle, Trump’s Attorney General and the federal Department of Justice are giving the boss’ company a green light for similar campaign crimes in 2020.

But New York Attorney General Letitia James doesn’t answer to Trump, and she has a power unique in America: the power to investigate and potentially dissolve the Trump Organization. It’s time to use that power.

Under the state’s Business Corporation Law—the modern version of a long-standing legal procedure with a rich history tracing back to the medieval English “writ of quo warranto” —Attorney General James can file a lawsuit in state court to dissolve a corporation, such as the Trump Organization, that is incorporated in New York. The test is whether the company “has exceeded the authority conferred upon it by law,...or carried on, conducted or transacted its business in a persistently fraudulent or illegal manner, or by the abuse of its powers contrary to the public policy of the state has become liable to be dissolved.” (This is a cousin of the separate legal provision under which the New York Attorney General successfully sued to dissolve the Trump Foundation.)

This type of lawsuit to dissolve a corporation isn’t common, but it isn’t rare either. Right now, Attorney General James is in the middle of a dissolution case against a credit card equipment leasing company, and just last year her office won another dissolution order against a different company. It’s true that neither of those were companies owned by the president of the United States—but it’s all the more important that the president should not get more lenient treatment for fraud than other citizens get. If no one is above the law, New York state law should apply to presidents and non-presidents equally.

Consider, then, the Trump Organization. That’s the small nerve center, based in Manhattan’s Trump Tower, that oversees a sprawling empire of about 500 tightly-controlled Trump businesses and real estate developments. Some of those, like the Trump National Doral Miami golf course, were legitimate businesses before the Trump Organization bought them. Others, such as the no-longer-Trump SoHo in Manhattan, seem on paper like they might be legitimate, but due to the Trumps’ poor business skills, can only be profitable through extensive fraud.

Still others, such as the Mar-a-Lago resort and the Trump International Hotel in Washington, D.C., began as legitimate businesses, but have become festering swamps of corruption since Trump entered the White House. And a few, such as a Panama City development dubbed “Narco-a-Lago,” or the failed Trump Tower Baku in Azerbaijan, seem to have been conceived at the start as vehicles for money laundering and corruption.

The case against the Trump Organization, detailed in a series of letters that we and our colleagues sent to Attorney General James and her predecessors, is extensive. Keep in mind that Michael Cohen already pleaded guilty to a campaign finance felony directly implicating Trump himself and Trump Organization officials knowingly and willfully.

Some of the charges on the company’s rap sheet—fraud against customers and investors, illegal political contributions, bribery, and obstruction of justice—reflect corporate misconduct of a relatively familiar type, but at an eye-opening scale. Other charges—violating U.S. sanctions against Iran, and facilitating the most flagrant presidential violations of the Constitution’s foreign and domestic emoluments clauses as a business model—are more unusual and also more compromising of our national security. The overall picture is a company soaked in a culture of corruption and impunity.

Dissolving the Trump Organization doesn’t mean closing office buildings, hotels, or golf courses, or putting innocent people out of work. The law provides that the Attorney General can work with a court-appointed receiver to develop a plan to ensure that relevant businesses can continue to operate and pay their staff and vendors while dissolution is pending in court, and allow for successful operation afterwards under new ownership.

Will Attorney General James use her authority to hold this corrupt company accountable? She’s not afraid to tangle with Trump. When he accused her—the first woman and the first African-American to be elected New York attorney general—of just being Governor Cuomo’s “tool” for “harassing” Trump’s businesses, she kept her cool and responded, “No one is above the law, not even the President. P.S. My name is Letitia James.”

It’s a name that Trump—as well as Don Jr., Eric, Ivanka, and the assortment of corrupt “business associates” sweating in Trump Tower—had better learn. Because if enough New Yorkers make their voices heard, her signature may soon appear on a lawsuit to dissolve the Trump Organization.

***

Ron Fein is the Legal Director of Free Speech For People. Jed Shugerman is Professor of Law at Fordham University School of Law. On Twitter @RonFein & @JedShug.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.