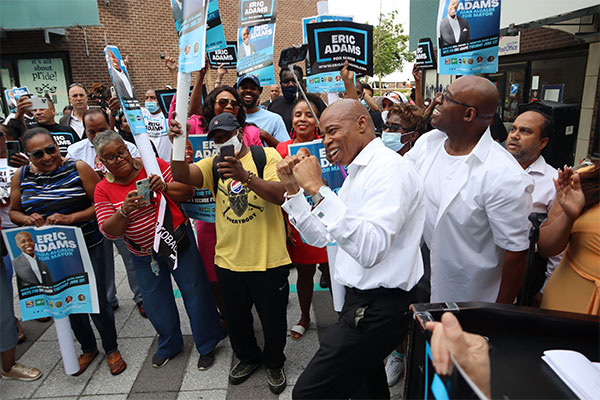

Eric Adams (photo: @ericadamsfornyc)

Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams emerged victorious last week in the Democratic mayoral primary and is very likely to become the next mayor of New York City. He ran a campaign largely focused on public safety, while weathering pointed attacks from his opponents on his record and vision for the city, which includes a wide variety of ideas on many issues. As several other candidates foundered, Adams sailed steadily to a narrow win, buoyed by a message that resonated with an electorate concerned about crime and quality of life in the city.

As one of few elected officials running in the primary, Adams was considered an early frontrunner and remained one throughout. He built institutional relationships for years and had an established campaign fundraising infrastructure, eventually raising more than $12.5 million in private and public matching funds and spending more than $10 million through June 21, the day before the primary. Outside groups also bolstered his campaign by spending more than $7.7 million on ad campaigns in his favor, giving him, in sum, a significant advantage over the candidates who came closest to defeating him.

Not only was Adams well-known, well-funded, and well-matched for the moment, but he was both disciplined and aggressive (perhaps at times to his detriment), consistent in his messaging, bolstered by labor unions and elected officials, thoughtful about policy, commanding of attention, hyperbolic, charismatic, and controversial. He had diverse, effective, and wealthy surrogates and supporters, and he campaigned with an unmatched combination of energy, intensity, and authenticity.

He overcame questions about his residency and ethics, his stances on stop-and-frisk policing and zoom schooling, and more, some of which dominated days of news coverage and televised debates leading up to primary day.

Adams ultimately won with 50.4% of votes after eight rounds of ranked-choice balloting were counted by the Board of Elections, a less than one percentage point victory over former sanitation commissioner Kathryn Garcia, who came in at 49.6%, just 7,153 votes behind. He won largely owing to Black and Latino voters. In early and in-person first-rank votes, he ran a near clean sweep through huge swaths of Central and Eastern Brooklyn, Southeast Queens, Staten Island's North Shore, and much of the Bronx, the city’s most Latino borough.

He had the helpful backing of Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr. and U.S. Rep. Adriano Espaillat, as well as Espaillat’s predecessor, former U.S. Rep. Charles Rangel. His active and diverse City Council endorsers stretched from Justin Brannan of Bay Ridge to Peter Koo of Flushing, Laurie Cumbo of Crown Heights to Ydanis Rodriguez of Washington Heights, and beyond. Adams won moderate white voters in neighborhoods in South Brooklyn and Central Queens, and was favored by voters living in NYCHA developments throughout the city, often the lone Adams territory within larger geographic areas won by competitors like Garcia and Maya Wiley, who came in third. He did well in Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods of Brooklyn and Queens.

In the fall general election, Adams will face Republican nominee Curtis Sliwa, the radio personality and founder of the Guardian Angels, among other candidates on the ballot. With nearly eight registered Democratic voters in the city to every Republican, Adams is heavily favored to win, though anything can happen over the course of more than four months.

[Read: In Mayoral Primary, Spending in Support of Adams More Than Combined Total for Garcia and Wiley]

In the very crowded and highly-competitive primary, Adams cobbled together a winning coalition that contained some contradictions, becoming the preferred candidate for both working class New Yorkers and hedge fund billionaires.

He won a steady drumbeat of endorsements from major labor unions, prominent federal, state and local elected officials, clergy members, activists, and even celebrities. Notably, he was not endorsed by the Brooklyn or Queens congressional delegations. U.S. Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, whose district overlaps with Adams’ Central Brooklyn base, endorsed Wiley and later picked Adams as his second choice when he seemed the heavy favorite in the race. U.S. Rep. Gregory Meeks, who chairs the Queens Democratic Party, endorsed Wall Street executive Ray McGuire’s mayoral campaign and also later chose Adams as his second choice.

In some ways, Adams seems to be the centrist reaction to two terms of Mayor Bill de Blasio, a progressive who massively expanded city government and spending, constantly called for tax hikes on the wealthy and vilified titans of industry, opposed charter schools, has been seen as soft on crime and unsupportive of the police, and was distracted by his national ambitions and uninterested in effectively managing city government.

Adams has, on the other hand, been much friendlier toward high-income earners and defensive of big business and real estate, and supportive of privately-run charter schools. He is viewed as tough on crime and a staunch defender of the NYPD’s role in society, even as he’s called for a series of policing reforms over decades and argued during the campaign that there are too many bad cops on the force who degrade the noble profession that he held and who he will seek to remove if elected mayor.

But Adams was nonetheless de Blasio’s apparent preferred successor. The mayor did not make an endorsement in the race – even with two of his own former senior administration officials on the ballot in Garcia and Wiley – but was reportedly working behind the scenes to convince several labor unions to back Adams’ campaign, which they did, and generally favorable toward Adams in public comments.

Adams has vowed to reign in wasteful spending while improving the social safety net, and promises to establish “real-time governance” using data to monitor and improve the functions of city agencies and to provide easier, centralized access to city services. He’s promised to run city government with precision and accountability, following the numbers not politics, and to hire top-notch people and let them use their expertise.

Adams pitched himself as the potential “blue collar mayor” of the city, projecting his own personal story of growing up in a poor household in southeast Queens, faced with the threat of homelessness. He relayed his experience with police brutality as a teenager, which in part led him to become a police officer to try to change the NYPD from within. Having spent 22 years on the force, rising to captain while regularly calling out police abuses, he struck a delicate balance as the law enforcement candidate who also wants to reform the culture of policing in the city. He said he is “someone who has been through a lot” who could lead New Yorkers “who have been going through a lot” given the pandemic and its many effects, as well as the several crises that existed in the city pre-covid, from high poverty rates to failing schools, crumbling public housing, high rates of gun violence in some communities, and more.

Adams pitched himself as a “pragmatic progressive” with a long list of solutions to the city’s problems, someone who can cater to the most vulnerable without alienating the city’s tax base of wealthier residents, business leaders, and real estate developers. His platform focuses on safety, equity, and growth, with promises to revolutionize how the city educates its children, helps lift people out of poverty, and keeps people out of the criminal legal system. He railed against the dysfunctionality of government and pledged to make it work better for regular people seeking permits or benefits.

Henry Garrido, executive director of DC 37, the 150,000-member municipal workers union, said Adams was the middle-ground candidate between the very pro-business ones like entrepreneur Andrew Yang and Wall Street executive Ray McGuire and the more left-leaning candidates such as Wiley and former nonprofit executive Dianne Morales. “I think he was able to thread the needle between the two with a message that was consistent and I think that working people made the difference,” Garrido said in a phone interview.

DC37 was among the major unions that backed Adams early, a few weeks after the Hotel Trades Council (HTC) endorsed Adams in early March, with 32BJ SEIU, the building workers union, also coming in for him that month and forming a powerful trio with largely Black and Latino workforces behind the candidate who would win the vast majority of working- and middle-class voters of color.

Garrido said his union made an “unprecedented effort” to help Adams, mobilizing its members and conducting outreach to union households, which make up roughly a third of the Democratic primary electorate. The union communicated the message “that we needed to see a City Hall that was going to respect the workers after everything that they've been through,” Garrido said of Adams, who pitched himself as the first-responder candidate, a former police officer who during the pandemic slept in borough hall, was out in communities, and focused on getting PPE to vulnerable populations, from transit workers to public housing residents.

“[W]e picked the right candidate for the right reasons with the right message and the voters agreed,” Garrido added.

Neal Kwatra, founder of Metropolitan Public Strategies, ran HTC’s independent expenditure effort, most of which was backing Adams. “In the 10-12 years I've been doing New York City politics, those three unions have very rarely sort of coalesced as quickly as they did in this race,” he said in a June 30 appearance on the Max Politics podcast, “and often have been, not for any particular reasons, but on opposite sides of these kinds of primaries. And so to have all three of them together I think was really impactful.” Kwatra spoke about how HTC spent about $1 million promoting Adams to its members as well as Latino and older New Yorkers.

“If you look at the map of where his votes came from, there is an economic throughline,” said Evan Thies, a spokesperson for Adams’ campaign. “It is largely lower- and middle-income working class neighborhoods. And those are the neighborhoods that care much more about the practical effectiveness of their government, rather than ideology.”

Among the more prominent moments for Adams' campaign came in May, when he received the endorsement of the New York Post editorial board, which praised his approach to public safety, small businesses, and fiscal responsibility. “His top priority has to be reversing the rocketing rise in crime, from shootings to subway safety,” the editorial board wrote. “Having been a police officer for 22 years, Adams understands the crisis. He articulates a clear, firm and common-sense route to cleaning up our streets.”

The endorsement came just two days after a high-profile shooting incident in Times Square, which further fueled concerns about rising violent crime in the city and seemed to only bolster Adams’ campaign message. The candidate seized on the incident, holding multiple press conferences in Times Square within 24 hours of the shooting. Even as many on the left questioned Adams’ celebration of the Post’s backing given its rightward tilt and closeness with former President Donald Trump, the focus on Adams as the candidate who could best speak to public safety issues only grew.

“When Eric talks about public safety, he is really sending a general message that he understands why people are unsettled right now and he's the guy to do something about it,” Thies said. “And that extends to our economy and public health.”

As the campaign progressed and gun violence continued to spike in the city, poll after poll showed that crime and public safety was the top concern for primary voters, followed by homelessness and housing. Those trends lent themselves to Adams’ strategy, which was always going to be focused on public safety, Thies said. “But the insight became that if New Yorkers trust you on public safety, they were going to trust you on the economy, they were going to trust you on public health. They were going to trust you to run the city in a more efficient, effective way. And we think that's more or less what happened.”

Candis Tolliver, vice president and political director of 32BJ SEIU, said Adams was a relatable candidate who ran “a great campaign from start to finish.”

“Our members are Black and brown and immigrant and they want to be respected by the police, but they also want to stay safe, and he talked about that in a way that a lot of candidates weren't talking about it,” she said.

Adams did face tough competition from a diverse field. He only just defeated Garcia, a first-time candidate with a similar ideological bent who surged after winning key endorsements from the New York Times and the New York Daily News editorial boards. But it wasn’t enough to overcome Adams’ advantages, from the message to the name recognition and resources.

Adams also barrelled to victory despite several campaign gaffes and bad headlines, while some of his progressive opponents collapsed. Comptroller Scott Stringer’s mayoral campaign was derailed by allegations of sexual assault and harassment dating back 20 and 30 years. Morales’ campaign imploded amid a staff revolt over working conditions and wages. Some of Stringer’s supporters rescinded their endorsements and switched to Adams including, notably, Espaillat, who is known for an ability to move votes in Upper Manhattan and the Southwest Bronx.

Adams faced attacks surrounding his residency, his real estate holdings, his taxes, his allies both current and past, and his entanglements in several ethics investigations over his career. He was also once a registered Republican between 1995 and 2002, providing other candidates with ammunition during the official debates.

Wiley took the lead in questioning Adams over controversial comments, including when he called stop-and-frisk policing a “great tool,” though that statement was somewhat taken out of context and he was able to point to his record criticizing the Bloomberg-era abuses of the tactic that became a strategy and explain his nuanced approach to its constitutional use. She also tried to question him for saying he would forego his security detail and carry a gun as mayor and when he said that off-duty officers should bring guns with them when attending houses of worship. He likewise parried those attacks and while they may have helped Wiley some in her efforts to woo progressive voters, they did not appear to hurt Adams much.

At the debates, there were tense exchanges between the two candidates but Adams repeatedly fell back on his record on reform and safety, while also lobbing his own criticism at Wiley’s record of running the Civilian Complaint Review Board, a police oversight agency.

Yang, who abandoned his early “happy warrior” persona and turned more acerbic as the mayoral race progressed, attempted to highlight the several ethics probes that have dogged Adams over the years. The two also filed separate complaints against each other over their fundraising for their mayoral campaigns. The bad blood between the two came to dominate some of the race, and while Yang faded, Adams held on, though Garcia was gaining on him, in part through an alliance with Yang that appeared to garner a good deal of Adams’ attention even as he insisted he was staying focused.

Adams’ willingness to punch back strategically and mostly matter-of-factly earned him good reviews of his debate performances, where at times he appeared content to sit back and let other candidates spar. If any of the many attacks or controversies hurt him, the damage was limited, though the extent to which Garcia gained ground through second-rank votes shows that Adams did alienate some number of voters.

In the late stages of the race, Adams did see Garcia as his apparent top rival, thanks to polling that showed her within striking distance and a possible victor. He publicly questioned her record as a manager, which was the central pitch to her campaign, as she juxtaposed her leadership of the 10,000-strong sanitation department workforce with his management of the borough president office with its staff of fewer than 200.

Even those who opposed Adams hailed his successful campaign. “Eric Adams, as much as I dislike some of his policies and the way he went about his campaign, he came across as authentic to a lot of people,” said Gabe Tobias of Our City PAC, which was promoting progressive candidates and did not want to see Adams win the primary. Progressives could not coalesce to defeat him, but not because they were running too far to the left, he said. “What happened on the left was we had three candidates, two of which, their campaigns really suffered badly for reasons that were totally not about ideology.”

It also helped, Tobias said, that his stances on policing only seemed moderate when compared with candidates who were pushing to “defund the NYPD” from anywhere between $1 billion and $3 billion. “It's easy for him to be painted that way sitting next to a defund candidate,” he said. “But when you look at the messaging that his campaign was paying to put out, the ads he was running, it was all like ‘I'm going to reform the NYPD. I'm gonna take on racism in the NYPD. I’m the one who knows how to change the system.’ He was saying all these left progressive things, it just wasn't as far left as other candidates.”

Chris Coffey was co-campaign manager for Yang, who was leading the race in early polls but eventually came in a distant fourth place. Yang clearly saw Adams as his strongest competitor and decided to run further to the right on policing, intensifying his positions as the campaign progressed.

“I think Eric had a good message and ran a good campaign,” Coffey said. “[He] had a really good coalition that he worked on for years and was relentlessly on message. He, for months, had been talking about crime louder and more efficiently than anyone else. Poll after poll showed that crime was the number one issue for Democratic primary voters and he did not deviate from his core messaging, and it worked and it paid off.”

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

Ben Max contributed to this article.