NYCHA Tenant Leaders: Where Amazon Never Arrived, New Opportunity Arises

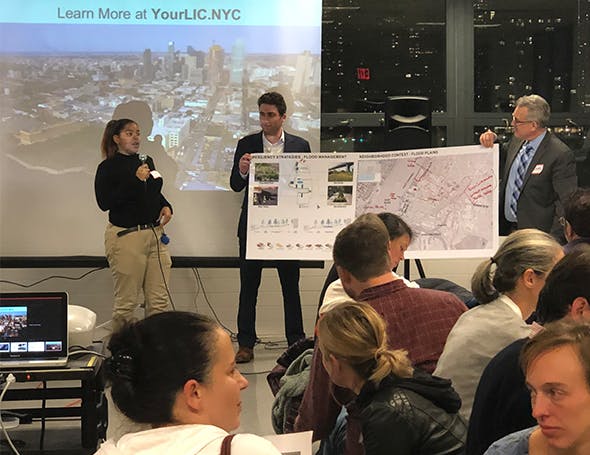

(photo: Your LIC)

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has not been equitable across New York City. While some New Yorkers have been able to work from home, or leave the city temporarily to wait the pandemic out, our NYCHA family has been devastated with the astounding loss of life and by an economic collapse at a scale we have never experienced before.

We have seen many people speak out about how to help NYCHA recover from this pandemic. On behalf of the nearly 17,000 residents of four Western Queens public housing developments, the virus has been catastrophic for our neighbors and the number one thing we will need coming out of this unprecedented time is jobs.

Thousands of our neighbors have lost their jobs and income, and we are ready to help New York City get back to work. NYCHA is the bedrock of Long Island City and the permanency of our homes provides an opportunity to access our residents for job opportunities. But we need the access, and we need to kickstart the creation of new opportunities to make up for the jobs that have been lost and may never return

We recently sat down with local Queens and citywide leaders in the workforce development community, convened by four developers (MAG Partners, Plaxall, Simon Baron Development, and TF Cornerstone) pursuing the Your LIC process to create a comprehensive plan for the Long Island City waterfront that is anchored with a strong jobs and commercial district.

We talked about an integrated, place-based workforce development plan that benefits the existing local workforce, including a community center that can connect all of Long Island City, flexible job training, pathways for high school students to find internships, services including childcare for families, and opportunities to strengthen soft skills.

It was uplifting to hear from our neighbors – non-profits, real estate stakeholders, workforce training experts, and residents – who have come together to begin to figure out real solutions to bounce back from this crisis and to build a future of opportunity.

Of course, we’re no stranger to fighting for the future of our community. Leading up to Amazon’s decision to pull their plans for ‘HQ2,’ we were making progress to ensure that the deal would work for all of us. This neighborhood was prepared to receive a job-training center, the launch of a workforce development program with LaGuardia Community College, modern after-school programs, and internships for our children.

For months following Amazon’s decision to pull out, we felt forgotten and it appeared that our goal of creating a Long Island City waterfront that would empower our community and create a significant number of jobs was lost.

Then last year, a new process emerged. The proponents of this new project began organizing a series of public engagements to hear firsthand what Long Island City residents want to see along the waterfront. Since the very beginning of the process, NYCHA residents have had a seat at the table, with hundreds from the community participating in the public workshops and online discussions. Our voices are finally being heard and we are continuing to meet with members of the Your LIC team to make sure that the proposal is one that works for all of us.

Since the first workshop in November of last year, we have discussed the importance of economic empowerment in workforce development, resiliency, and creating connected public open space, and schools, places for the arts, and other community spaces.

We know that the buildings proposed on the waterfront may be tall and dense, and some people will have concerns about that, but we’ve been seeing towers rise in Long Island City for a long time. In those developments, residents come and go, but the residents in NYCHA developments in Western Queens are permanent, and it’s time for a proposal that benefits and draws from the human capital in our communities.

The need to deliver jobs – here in Western Queens – and community benefits are more critical than ever for the future of this place. These are the types of tools and investments that make a real difference in people’s lives and will do so for our children, too.

As we look forward to planning for the future of the Long Island City waterfront – and toward the future of our city as a whole – we can’t afford to squander yet another opportunity to create jobs and to deliver progress right here in a community that both needs it and deserves it.

When crises hit New York City, so many turn to NYCHA to lament how public housing residents are disproportionately impacted, but when given the opportunity too little action is taken. This is our community. Please don’t forget us once again. Support us as we build a strong future for NYCHA and our neighbors.

***

Carol Wilkins is the president of the Ravenswood tenants association; April Simpson-Taylor is the president of the Queensbridge tenants association; Claudia Coger is president of the Astoria Houses tenants association; and Annie Cotton-Morris is the president of the Woodside Houses tenants association.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

City Budget Crisis Threatens Lifeline for Day Laborers and Immigrant Workers

NICE staff and volunteers deliver groceries to workers impacted by COVID-19

“The rags were so filthy, and we had no soap and little water to clean them, so we felt like we were spreading the virus in the subway car by our cleaning…We started on Monday, but they did not give us masks ‘til Wednesday…The gloves they gave us were for making sandwiches, not for cleaning! They would break, and there were no more, so we brought our own…I worry: How many people will get sick because these cars were “cleaned” this way?”

-Susanna, a New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE) respondent reporting unsafe working conditions and fearing other New Yorkers would get sick in ineffectively-cleaned subways cars.

Susanna worked cleaning subway cars to keep essential workers and all New Yorkers safe during the near-lockdown and as the city “reopens,” but the contractor was cutting corners and putting profit over the health of workers and the public. With NICE’s support, Susanna protested her sub-prevailing wage pay, and what she saw as unsafe working conditions that ineffectively cleaned subways and posed risks to all New Yorkers.

Susanna’s voice is one the New York City Council should hear as Council members decide how to distribute discretionary funding. Many immigrant-led/serving nonprofits that have been critical lifelines for immigrant workers are at risk of losing their funding due to the city budget crisis. This would be tragic for the organizations, immigrant workers and families they serve.

Thankfully, the City Council can make these New Yorkers a priority as negotiations proceed leading up to a new budget by July 1.

Research by New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE) -- a nonprofit that supports day laborers and other low-wage immigrant workers and their families through its Worker Centers in Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx -- shows how these communities are extremely hard hit by the pandemic. Survey data are grim: the pandemic sharply increases NICE families’ risk of poverty and homelessness.

Only 20.5% had worked at all during the pandemic; 90% had not worked in over four weeks. As a result, 41% of respondents reported being at risk of losing their housing, and 32% feared they could be at risk. Those at risk lived with an average of 2.2 children, nearly all U.S. citizens. Research shows homeless children face a “cascade” of preventable harms making it harder to learn and thrive as adults. NICE’s data point to a developing crisis we can still act to prevent.

Moreover, of those surveyed, 36% reported COVID-19 symptoms (loss of taste/smell, cough, difficulty breathing). Actual infection rates could be higher, because infection precedes symptoms. Equally worrisome: 41% reported underlying conditions (eg asthma) that can worsen covid’s morbidity. Finally, 15% reported “acute anxiety, depression, or suicidal thoughts as a consequence of Covid19.”

NICE’s strategic thinking is to respond over what the Centers for Disease Control call the “lifecycle” of the pandemic, which will likely include the immediate crisis; phased reopening by work sector, including construction work; possible COVID-19 case upticks, and re-shutdowns; development and broad use of better treatments and a vaccine; and transition out of the pandemic.

Efforts like these will be essential in each pandemic lifecycle stage. First, NICE members work mostly in construction, one of the first large industries in New York City’s phase 1 "reopening." The research NICE has done (and seeks to continue) could offer real-time data on upticks – the canary in the coalmine – for policy-makers. Faster response can save thousands of New Yorkers’ lives. Second, NICE and similarly-situated organizations are directly linked to the most vulnerable New Yorkers who are unlikely to be contacted by or respond to most polling or online surveys on the coronavirus (including the CUNY School of Public Health’s well-designed weekly 1,000-person survey on COVID-19 impacts). Third, immigrants’ deep trust in their organizations makes them essential partners as we move through the pandemic lifecycle. These organizations can help ensure all New Yorkers have fair access to a vaccine, once we have one. But they must survive financially to do this work, which City Council funding can help ensure.

Finally, including funding in the New York City budget for organizations that support immigrant workers will keep all New Yorkers safe now and in the long-run. Consider Singapore, which nearly quashed the pandemic, but neglected its immigrant workers, causing COVID-19 cases to rebound. Just as Susanna worried about people who could get sick from a badly-cleaned subway car, all New Yorkers should want Susanna to have proper gloves and masks, and want the construction workers, nannies, and deli workers who are part of the fabric of New York life to be as protected as most everyone else. New York is a resilient place, but must also be a just and smart place, where it protects all New Yorkers equally, so we can all live safely and well.

***

Manuel Castro is the Executive Director of New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE). On Twitter @NICE4Workers. Robert C. Smith is a Professor in the Marxe School at Baruch College and the Sociology Department, Graduate Center, CUNY, and co-author of Immigration and Strategic Public Health Communication (2019, Routledge).

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Why New York City Must Put Educators and Counselors, Not Cops, in Charge of School Discipline

Mayor de Blasio gives remarks on school safety (photo: Rob Bennett/Mayor's Office)

Amid protests spurred by the police killing of George Floyd, activists from Minneapolis to Chicago to New York City are pushing to reduce the presence of police in schools, and a number of school districts are heeding their call. Most recently, New York City Council Members Mark Treyger and Donovan Richards are proposing to end the ties between the New York Police Department and Department of Education.

They have a point. Reducing the number of cops in schools need not diminish safety. However, with 25 of the nation’s largest school districts now outsourcing at least some school safety to police departments, severing those ties will require the development of new methods for de-escalating conflict. Districts will need to learn from successful experiments that engage students, teachers, and administrators in improving school culture in ways that promote both safety and learning.

The call to reduce police presence in schools follows a decades-long escalation. In the 1990s an increase in gun violence in schools led President Bill Clinton to sign The Gun Free Schools Act, which made zero-tolerance school discipline a national movement. The law initially mandated punishments for firearms possession—mandates that were later expanded to include a range of crimes and infractions.

By 1998, in the first takeover of its kind, then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani arranged for the New York police department to take command of the education department’s Division of School Safety; he did so over the objections of at least two schools chancellors. New York City has had more than 5,000 police personnel assigned to schools in recent years, equivalent to one of the largest police forces in the country; by contrast, the combined number of school counselors and social workers was less than 4,300 in 2019.

Following the shooting at Columbine High School, in Colorado in 1999, the police presence on school campuses nationwide grew steadily with so-called School Resource Officers typically hired, and paid, by local police departments.

Violent crime and thefts in schools declined 70 percent between 1992 and 2013 even as some high schools reported an increase in discipline problems after police appeared on campus. Indeed, schools with officers reported five times the number of arrests for "disorderly conduct" as schools without them. A lack of training in “positive behavioral interventions” has led many schools to become “overly reliant” on harsh discipline and to criminalize infractions that, in the past, might have merited a scolding from the principal, according to a recent Clemson University study.

The increased police presence and zero-tolerance policies have had a particularly adverse impact on students of color. Despite efforts under the Obama administration to limit the role of police in school disciplinary matters, students of color have been targeted for suspension and arrest in large numbers nationwide. Although suspensions have declined in recent years, overall arrests have increased; Black students, who make up just 15.5 percent of all public school students, accounted for over one-third of all school arrests, according to a 2018 government study, which found that “implicit bias” was partly to blame for the increase. Black boys are arrested three times more often, and Black girls 1.5 times more often, than white boys.

In New York City, overall suspension rates declined by 39.4 percent in the decade leading up to the 2016-17 school year. While the suspension rate of Black middle- and high-school students also declined during that period, it remained 2.8 times higher than that of white students.

At the same time, the presence of metal detectors, security cameras, and security guards makes kids of color feel less safe in school “physically and psychologically,” according to the National Association of School Psychologists, which can, in turn, have a detrimental impact on students’ ability to learn. (Nor is there clear evidence that the use of such restrictive security equipment is “effective in preventing school violence,” according to the study.)

By contrast, research has shown a strong positive connection between nurturing school environments and learning. A recent study of high-poverty New York City schools, which looked at the impact of neighborhood violence on standardized test scores, found that the performance of students exposed to violence suffered if they attend schools with weak climates; by contrast students who attend schools perceived as both safe and “having the strongest sense of community,” suffered no reduction in test scores even if they were exposed to violence.

Creating the kinds of nurturing environments associated with both safe schools and better education outcomes requires an all-hands-on-deck approach. Schools need to foster new methods, such as peer-mediation and behavior-management strategies that deescalate conflict and put educators—not police officers—in charge of the vast majority of discipline infractions.

Take the case of the Bayard Rustin complex of six small schools in New York City, which, in 2017, began petitioning both the education and police departments to suspend unannounced metal-detector screenings at the school building, where 96 percent of students are people of color. The screenings were conducted by the NYPD even though discipline problems in the building “are rare” and the school principals opposed them—more than 80 percent of students said they felt safe in the school building, according to education department surveys. The New York Civil Liberties Union was brought in to mediate a discussion among the schools and the education and police departments. In 2019, when the NYPD was expected to install permanent metal detectors, the students finally won a partial victory; while Bayard Rustin remained a random-screening site, permanent metal detectors were never installed.

The battle at Bayard Rustin—and the students’ modest success in keeping out permanent metal detectors—was a school culture and curriculum that encouraged students to grapple with real-world problems. The Bayard Rustin complex is run collaboratively with educators at all six schools jointly determining the use of common spaces and policies. Three schools are members of the highly-regarded New York State Performance Standards Consortium, which allows students to complete in-depth, long-term projects, often tailored around student interests, in lieu of most standardized tests.

The fight against metal detectors was led by Bayard Rustin students with the support of educators. Brady Smith, principal of James Baldwin, a “transfer” high school for over-age, under-credited students who struggled at previous schools, and a member of both the performance standards consortium and the progressive NYC Outward Bound network, persuaded his fellow principals to appoint a student advisory council to address the metal-detector problem. He also insisted that the student council include some “marginalized students,” noting: “A lot of schools create pathways for student leadership that appeal to a particular type of student—the extrovert, charismatic student.” For this committee, he wanted the kind of students who would focus on “issues,” rather than having “good events.”

Similar efforts to engage students in critical problem-solving have borne fruit elsewhere. In Leander, TX, a large district outside Austin, a years-long, student-led anti-bullying campaign has not only mitigated a major problem at district schools, but created leadership opportunities for teens. The effort, fostered by teachers and administrators, grew out of a nearly four-decade commitment to a school-improvement philosophy that encourages problem-solving at all levels of the school—from students to administrators.

Despite a growing movement to cut police budgets, too many officials still view the police as a school safety panacea. Although crime in New York City schools is at record lows, Mayor Bill de Blasio has increased the school-safety budget by 25 percent since taking office in 2014. He has also called for a 1.36 percent increase, to $427332 million, in spending on school safety officers next fiscal year, even as he plans to cut $827 million from the education department and prepares to borrow $7 billion to make up for shortfalls in the city’s operating budget.

Getting cops out of schools will present both opportunities and challenges, especially in mitigating the kind of childhood trauma that often leads to school violence and discipline problems. As of 2017, nearly 29 percent of the school incidents in New York City involving police or safety agents involved a “child in crisis,” and resulted in the child being taken to a hospital for a psychological evaluation; by contrast, only 12 percent of the incidents resulted in an arrest.

For the transition to be successful, the education department will need to retrain school safety officers, especially in so-called restorative justice practices that include addressing sources of friction before they escalate, and working with both victims and the accused to develop long-term solutions, and to “foster understanding” and “impose fair punishment.” And as principals take charge of supervising school safety, the department may also need to reduce some administrative burdens now shouldered by school administrators.

In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, students who have spent months under lockdown have suffered increased depression and anxiety that can impede learning—the kind of trauma that most benefits from mediation by educators and counselors, and not police.

***

Andrea Gabor is Bloomberg Chair of Business Journalism at Baruch College/CUNY and author of After the Education Wars (The New Press, June 2018). On Twitter @aagabor.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.