Informal Recyclers are Essential to a Just and Green NYC; Here's 7 Things We Must Do To Help Them Survive

Canners redeeming their work (photo: Carlos Rivea for Sure We Can)

In New York City, there are an estimated 8,000 informal canners, or people who collect, sort, and redeem deposit-based containers for a living. Earning a nickel per can or bottle, canners straddle a liminal space in society: though often visible pushing carts with bulging bags through the city, they work in the shadows because of fear of harassment, shame, and a lack of public support.

Canners are indispensable to New York State’s environmental sustainability efforts and to the local economy. Each year, more than 5 billion containers are redeemed in New York, generating over $400 million for the economy and funding environmental campaigns.

Canners play an important role in achieving these results. For example, the 800-plus canners who frequent Sure We Can, the only not-for-profit redemption center in the five boroughs, redeemed 12 million deposit-based containers and returned over $700,000 to the local community last year alone. Further, Sure We Can supports eight green jobs and educates hundreds of K-12 and college students about urban environmental and social issues.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has been disastrous for informal workers like canners. The current crisis exacerbates long-standing systemic economic, social, and environmental inequities and poses numerous public health risks to canners. Bottle redemption is considered an “essential service,” but economic support and social protections are not extended to canners. Many Asian-American canners have reported increased harassment and stigmatization. And in economic downturns, when unemployment swells, the number of people who turn to canning to survive increases.

Today, supporting canners is more important than ever. Here are several short- and long-term actions you can take to help canners and grow a green and just economy as we rebuild from the COVID-19 crisis:

Acknowledge and thank canners in your neighborhood for the services they provide. Canners are our neighbors: they often collect containers near their homes, cleaning up the neighborhood in the process.

Separate redeemable containers from other plastic, glass, and aluminum containers, and set them aside in a clear or marked bag for canners. If you live in a large apartment building, ask the maintenance staff to aggregate redeemable containers for canners.

Offer clean, unused, and sealed personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves, face masks, and alcohol gel, to canners. Canners work independently and may not have access to PPE.

Advocate for economic relief measures for all informal workers, regardless of their tax-filing status. Support local organizations that are dispensing relief funds to those most impacted by the crisis.

Support the “Community Organics and Recycling Empowerment (CORE) Act” introduced by City Council Members Keith Powers and Antonio Reynoso. The CORE Act proposes the creation of community drop-off sites for the collection of organic waste and electronic waste, which currently contaminates the recycling stream and is hazardous to canners. Further, the CORE Act will create hundreds of green jobs.

Advocate for canners and informal workers to be included in decision-making processes across all levels of government. In cities around the world, the integration of canners into municipal solid waste management systems yields abundant social, economic, and environmental benefits.

Support legislation to increase the redemption value from 5-cents to 10-cents per container and to expand the type of containers eligible for redemption. Similar changes in Oregon have pushed recycling rates to over 90%. Further, updating the New York State “Bottle Bill,” which has remained largely unchanged since 1982, will provide canners a fair wage reflective of the value of their services.

As New York City enters phase 2 of “reopening,” canners should no longer be relegated to the shadows. We must recognize, advocate for, and advance the positive economic and environmental contributions of canners so as to realize the just and green New York City we all want.

***

Chris Hartmann, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Public Health at SUNY Old Westbury and a board member of Sure We Can. Christine Hegel, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at Western Connecticut State University and a board member of Sure We Can. Chicago Crosby is a canner and board member of Sure We Can. Josefa Marin is a canner and board member of Sure We Can. On Twitter @SureWeCanNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Who Traffic Enforcement Agents Really Are, and Why They Must Remain Part of the NYPD

Traffic Enforcement Agents take a knee

On Thursday, June 11, hundreds of New York City Traffic Enforcement Agents and Supervisors stopped work for eight minutes and 46 seconds to commemorate the tragic murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Employed by the NYPD, these members of the Communications Workers of America (CWA) were participating in a nationwide CWA job action to support the massive protests sweeping the country on behalf of racial justice and an end to police violence.

Is it surprising that these NYPD employees staged a job action for racial justice? If you knew who they were, it wouldn’t be. CWA represents approximately 2,800 agents and 400 supervisors who work in New York City Traffic Enforcement. Over 95% of them are people of color—primarily immigrants from Bangladesh and Africa, and Latinos and African-Americans. Traffic agents are extremely low-paid: their salaries start at just over $41,000 and top out at $50,000 after 10 years on the job. What’s worse, on average, 100 agents each year are physically assaulted by members of the public angered by a parking ticket or a disagreement at an intersection. The verbal insults—many of them racial slurs—are too numerous to count.

That is why it is especially disappointing to see these workers targeted, even inadvertently, by the leaders of two organizations we normally consider allies, in a recent column in this publication advocating the removal of traffic enforcement from the NYPD.

The recent Black Lives Matter protests have sparked an enormous grassroots demand for fundamental reform of the police department, a stance supported by the CWA. But moving Traffic Enforcement out of the NYPD is not meaningful reform—it is merely cosmetic budget-shifting in the name of reform. And such a move would utterly ignore the deeply felt concerns of the 3,200, overwhelmingly of-color workers who would be directly affected.

The authors raise serious concerns about the discriminatory impact of policing practices on Black and brown pedestrians and drivers—practices that CWA and the Traffic Enforcement Agents vehemently oppose. But these issues literally have nothing to do with the TEAs and Supervisors. To list just a few of the misleading arguments:

The authors decry racially discriminatory policing of social distancing during the pandemic, but traffic agents have had no authority to police social distancing.

The authors state that Black and brown New Yorkers receive 89% of the tickets issued for jaywalking or mid-street illegal crossing, but traffic agents have no authority to police jaywalking and never issue tickets for that offense.

The authors cite figures showing that Black and brown drivers are far more frequently pulled over by police and even more frequently searched for drugs and alcohol, but TEAs have no authority to pull cars over.

The bottom line is that CWA-represented Agents and Supervisors are only authorized to issue parking tickets and direct traffic in busy intersections. The only moving violations they ever issue occur when drivers “block the box.” Somewhat ironically, they do issue tickets to drivers who park illegally in dedicated bike lanes, something that Transportation Alternatives supporters surely appreciate.

Why, then, do our members care so deeply about remaining in the NYPD? The answer is simple: they believe the uniform provides a measure of safety. Directing traffic and writing tickets earns these agents no love or affection from most New Yorkers. When the traffic bureau was part of the Department of Transportation, agents were routinely derided as “Brownies.” Assaults—literally physical attacks in which faces were punched and limbs were broken —peaked in the early ‘90s at around 600 per year, a trend exacerbated by the late-1980s scandal in the Parking Violations Bureau. The agents fought for years to achieve "uniform status" in order to gain a measure of respect and security. They deeply believe that if they return to the Department of Transportation, disrespect from the public will increase and the assaults and racial slurs will escalate dramatically.

CWA and the Traffic Enforcement Agents and Supervisors support genuine reform of the NYPD. We want to see an end to the now-endless litany of young Black men who have suffered at the hands of police across the country. But moving traffic out of the NYPD satisfies only one need—the claim of a big reduction in the NYPD budget—and actually changes nothing. And there are 3,200 women and men, mostly of-color, who will be deeply hurt if such a change goes through. We urge the City Council and the Mayor to reject this idea.

***

Bob Master is Assistant to the Vice President of CWA District One and Rebecca Greene is a Traffic Enforcement Supervisor and Member of CWA Local 1181. On Twitter @cwabobmaster.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Learning the Right Health-Care Lessons from the Covid Crisis

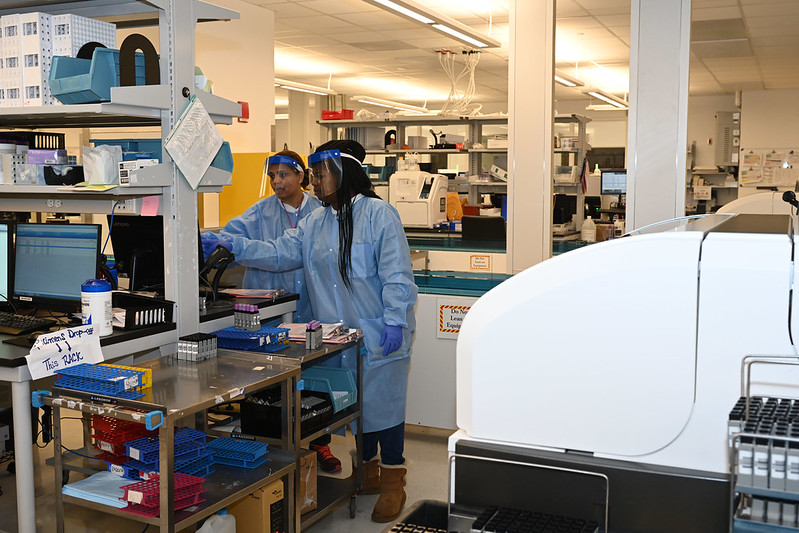

Health care lessons from the coronavirus crisis (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

The saying “a crisis is a terrible thing to waste” is cliché, but true. Out of the coronavirus pandemic can come positive change, but we must learn the right lessons. At the peak of the COVID-19 crisis in New York some hospitals were overwhelmed – short of personnel, ICU beds, ventilators and PPE. But that does not mean, as some have argued, that more permanent hospital beds are needed.

To draw that conclusion and act upon it would be an extremely costly mistake that doesn’t address the real challenges facing New York’s health-care system. What is needed is an acceleration of the transition from a system of hospital-based ‘sick care’ to one of community-based health promotion and care.

While this state has the most expensive Medicaid costs in the country, we have mediocre results in prevention and treatment, according to the Commonwealth Fund Scorecard. We focus on costly hospital beds and services that are accessible and satisfactory (except for their high cost) to those with higher incomes, but underinvest in the primary care networks and population health initiatives that could give us a truly coordinated health-care system that prevents and manages illness and reduces the need for hospital care.

New York State has a total of about 21,200 hospital beds, or 2.5 per 1,000 people, down substantially (approximately 23%) over the past 15 years. The number of patient discharges (a measure of the number of people hospitalized) and length of hospital stays has also declined. Meanwhile, the number of ambulatory care facilities such as school- and hospital-based clinics has tripled. These would all seem to be good trends that indicate people are getting more outpatient care and needing hospitalization less.

But the number of pregnant women who receive no prenatal care and the number of New Yorkers without a primary care doctor have remained relatively unchanged, hovering at about 10 percent and just below 20 percent, respectively. And the number of emergency room visits per year had increased to almost 400 per 1,000 residents, 120% of the number in 2005, before the pandemic hit.

The COVID-19 crisis has been particularly acute in primarily poor neighborhoods and communities of color, where hypertension, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses are most prevalent. Investing in more and better health care in these neighborhoods will contribute to longer and safer lives. Much more attention is needed to treating people near where they live and creating trust in and reliance upon local clinics, nutritious food options, and behavioral health services so that visits to emergency rooms are not the first contact with the health-care system. This is where we should put our focus and funding, not on keeping thousands of costly beds open in case of severe emergency.

But that doesn’t mean we don’t also need to make changes in order to better respond to the next viral or other health crisis. In New York we operate our health-care system through separate silos of services: a hospital bed silo, a behavioral care silo, a nursing home silo, and multiple ambulance services. Moreover, many entities within each silo compete with each other for patients. In an emergency, all of these distinct organizational structures should be prepared to operate as if they were one, managing capacity intelligently. This means the state Department of Health must be placed clearly in command of all health-care facilities and providers, notwithstanding resistance that can be expected from some in the industry.

At the first recognition of the pandemic the state should have been able to put into operation a plan designed well in advance and tested once a year to ensure all aspects of the health-care system know their roles and could immediately function in a coordinated fashion. The system should have been organized by region, each with an agreed upon lead with hospitals, clinics, doctors, offices, EMTs, and ambulances working together. Two or three hospitals per region should be established as first receivers so ambulances, doctors, and clinics know where to send patients.

PPE would be distributed across the system and if and when a virus spreads hospitals could be added as receivers, staggered to account for discharges. Additional bed capacity can be added in existing and temporary facilities if needed, as occurred at the height of the covid crisis. Long-term care facilities would be incorporated into the emergency system. Outpatient clinics would be required to extend hours. Such a plan requires leadership and execution at the state level, so that when the red light goes on all the players understand they belong to the community effort.

More beds in an uncoordinated system will cost money on an ongoing basis without providing the ability and agility to control a pandemic if and when it happens. We need coordination, speed, clear decision-making and lines of authority, and surge capacity, not more permanent hospital beds. We have a dysfunctional and expensive ‘sick care’ system that doesn’t deliver health improvement to a large portion of the population. It needs to be reconfigured; we have learned enough from the covid crisis to make it happen.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of the Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018. Stephen Berger was Chairman of the New York State Commission on Health Care Facilities in the 21st Century.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.