The Governor’s Clemency Negligence

Governor Cuomo (photo: Mike Groll/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo)

At his daily coronavirus press briefing on Sunday, April 26, Governor Cuomo was asked whether he had any plans to grant broad clemencies to people in prison, particularly to vulnerable populations. His testy and dismissive response – “How about if they are violent and just started their sentence?” – was telling. Presumably, the governor meant to remove from consideration people he believed remained a threat to public safety and had not been sufficiently punished.

The reporter’s question was ultimately about the perilously unsafe conditions in New York state prisons as nearly 1,300 staff and incarcerated people have already tested positive for COVID-19. The governor’s apparent disregard for anyone recently convicted of a violent crime is reminiscent of times when convicted people were sent to places like Devil’s Island where leprosy and other diseases flourished, and tens of thousands of incarcerated people died.

Public health officials in New York, nationally, and all over the world have cited prisons as petri dishes for the spread of the virus, and have called on government leaders to release people so that it becomes somewhat possible to maintain social distance and stay alive in prison. Otherwise, especially for those the CDC defines as most at-risk from COVID-19, numerous prison sentences will transform into death sentences.

Even engaging in the clemency debate on the terms spelled out by the governor, what about releasing those convicted of violent crime who have served twenty, thirty, forty, or more years? Countless people in New York state prison have served decades, many defined by remarkable achievement and transformation.

They have completed, facilitated, designed, and implemented programs; they have obtained GEDs, associates, bachelors, and masters degrees; they have learned several trades; they have the support of people inside the prison and robust re-entry plans with family members who are waiting, and praying, with open arms for their release. And, to the governor’s stated concern about violence, they are older and, as every study ever done shows, have aged out of any likelihood of committing another crime. They are no threat to public safety, and have much to offer their families, communities, and society at large

Thousands of people in New York State prisons have submitted clemency applications, many well before the coronavirus outbreak. Many of the applicants are elderly. Many have health issues. Very few “just started their sentence.” Countless among them merited clemency in their own right before COVID-19 came behind the bars. Now, their meritorious applications are joined by the urgency of a public health crisis of untold magnitude.

While clemency is usually cast as an act of mercy or charity, at this moment it is a matter of life and death. The governor’s power to grant clemency is firmly rooted in the state constitution. It is well past time for Governor Cuomo to use it.

***

Steven Zeidman is a professor of law at CUNY School of Law. On Twitter @SteveZeidman.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The ‘Wartime Budget’ New York City Needs

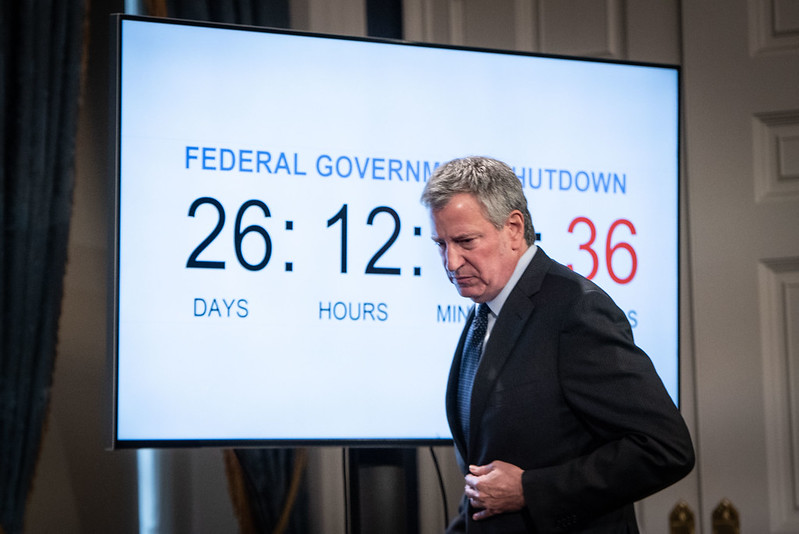

Mayor de Blasio is facing difficult budget choices (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Mayor de Blasio called the Executive Budget he presented on April 16 a “wartime budget.” With New York City’s economy shut down virtually overnight and without a clear path or timeline to reopening, that is definitely what the circumstances require. But, we don’t quite have one yet.

Estimates of cumulative city revenue losses from the city’s budget office and outside fiscal monitors range from $7 billion to $15 billion for this and next fiscal year, but there is no precedent for the current situation so modeling on the experience of past recessions could well understate both the extent and the timeframe of the losses. Absent a large infusion of federal assistance, the best way to close the city’s budget gap is more and larger expense reductions, not tax increases or borrowing.

While the Executive Budget, which will form the basis for negotiations with the City Council, shows an overall year-to-year reduction of 3.6 percent from the budget adopted last year, it would increase city-funded expenses by 1.3% -- not as generous as the annual growth in recent years (which averaged 4.8% for most of de Blasio’s tenure) but not a cut. Significant withdrawals from reserves and the Retiree Health Benefit Trust as well as $2.7 billion in cost savings currently make up for the anticipated loss of tax revenue. But most of these are one-time savings (and many caused by the impact of the virus and stay at home order); if tax revenue losses are higher and last longer because the economy doesn’t bounce back quickly, these actions will not be sufficient.

Moreover, there is little indication that the City Council is on a “wartime” footing and will refrain from its usual demands for more spending. In its formal response to the mayor’s Preliminary Budget, issued after the virus shutdown began, the Council listed many areas it believes should be fully funded and proposed adding more than $1.4 billion in new spending but suggested only half as much in spending reductions to offset it (and some of those savings ideas have been incorporated into the Executive Budget to offset current expenditures). And new legislation proposed by the Council last week, characterized as a coronavirus aid package, would impose new costs on businesses that would make it even more difficult and costly for them to operate and hence, to pay their employees and taxes.

The mayor is holding back on more cost-cutting in the hopes that the federal government will come through with financial assistance to help close city and state budget gaps. But the most recent aid package passed by Congress didn’t include state and local aid and Senate Majority Leader McConnell and other Republican legislators say they are not in favor of this type of assistance. Indeed, McConnell effectively said ‘Let ’em go bankrupt.’

Federal budget relief for states and localities is clearly warranted and some will eventually come through, but it will be preceded by a fraught, ideological battle about blue states’ high taxes and overspending and cannot be counted on to happen in time for final New York City budget adoption (on or before June 30). And New York State, which is facing its own $13 billion revenue loss, is not going to come to the city’s rescue. Indeed, aid reductions and cost-shifting by the state could make the city’s problem worse. So there needs to be a more serious plan to ensure that the city can balance its budget with little or no federal help.

It is difficult to cut city programs and services. Each one has a constituency of supporters who believe fervently in its importance. Many of the cuts and reductions in the Executive Budget, though relatively small and temporary, have already been decried by those who especially care about them, e.g. advocates of recycling urge restoration of the costly organics collection program; social service youth care providers denounce the suspension of the summer employment program. One of us is especially pained by the cut to a nationally recognized college completion program she helped create, CUNY ASAP.

But the city simply does not and will not have the money to keep doing everything in an annual budget that has grown to well over $90 billion. There will have to be deeper cuts and sacrifices of favored programs and activities than the Executive Budget proposes, at least for now. Labor contracts should be re-evaluated in light of the pandemic and efforts to achieve more productivity negotiated with public employee unions. Otherwise, the city risks having to take more draconian measures, such as laying off public employees and imposing cuts to essential services as the coming year unfolds.

Two things that should not be done except as a last resort are raising taxes and/or borrowing to pay operating expenses. It should be evident to the mayor and the Council that raising taxes now would only exacerbate the risks to the already fragile revenue base, as many business owners consider closing and the pandemic is causing many people to consider leaving New York.

Nor is borrowing a good idea. Borrowing money to fund capital projects is appropriate because the value of the expenditures for things like roads, school buildings, and water mains – their ‘useful life’ – lasts for years and it makes sense to pay for them over a long time period. In contrast, paying for current expenses like employee salaries pushes the responsibility for payment into the future, burdening taxpayers for years with debt service for services that have already been consumed.

Every $1 billion in borrowing now will cost at least $65 million a year for debt service every year the loan is outstanding (based on 5% interest on a 30-year loan). Especially now, every penny of the money that would go to interest is needed to pay for the costs of operating city agencies.

There will undoubtedly be many, including Council members and public employee unions, who endorse the borrow now, pay later approach because it avoids making hard decisions in the short run and allows city services and agencies to keep operating as if there is no problem. But if the economy and its tax revenue do not bounce back, the gap between costs and income will remain and more borrowing will be needed to close it.

This is a particularly frightening prospect to those, like one of us who was a First Deputy Budget Director in the mid-seventies, who remember the massive retrenchment and downsizing of city government during the fiscal crisis of that time. Instead of aligning the cost of city services with its revenue, it had borrowed money to pay its operating expenses year after year, until eventually institutions would not loan any more money because they realized the city would never be able to pay it back. There was literally not enough cash on hand to make payroll. (See this story for a good summary, with warning signs for today, of the fiscal crisis of the 1970s.)

Many felt it was acceptable when Mayor Bloomberg borrowed $2.1 billion to pay operating expenses right after September 11, 2001. But the nature of that crisis was quite different than what we face now. Only lower Manhattan was directly impacted and the rest of the economy, though suffering temporary setbacks, was able to quickly recover, so the city’s coffers could be replenished. In addition, Mayor Bloomberg instituted significant cost controls, including personnel reductions. The Council also agreed to an 18% increase in property taxes, and the state Legislature extended a 14% surcharge on the city personal income tax, neither of which would make sense in the current situation.

If, instead of making tough decisions about curbing expenses now, the mayor and Council decide to try and kick the can down the road by borrowing, the state Legislature should deny permission unless and until the city can demonstrate that it is holding the amount borrowed to an absolute minimum by taking every other possible step – including savings on personnel costs – to reduce the city-funded operating budget. If borrowing is permitted, it should be conditioned on the creation of a ‘control period’ during which the city’s finances are subject to oversight and intervention by the Financial Control Board, created during the ‘70s fiscal crisis to help ensure that the city adopted balanced budgets and sound financial management. Since 1986 the Board has served in a monitoring role, but this could be the time to bring it back into action.

Correction (May 7): In the original version of this piece, we incorrectly stated that after 9/11 Mayor Bloomberg negotiated a multi-year no-raise contract with the teachers’ union. That contract was negotiated during the recession in 2008, and mention of it has been removed. Mayor Bloomberg signed a 30-month contract with raises following the city-wide pattern of 4% a year with the teachers in early 2002 when he was pursuing Mayoral control of the school system. But, as we said, the city budget adopted post 9/11 did include significant cost cutting, including early retirement measures, attrition, and difficult and unpopular agency spending reductions such as curtailing plastic and glass recycling.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018. Norman Steisel was a First Deputy Mayor of New York City, Sanitation Commissioner, and First Deputy Budget Director, all between 1974 and 1994.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Cuomo's Density Dodge: Pandemics Aren’t Anti-City, Failure to Act Early Is

An altered image from one of Gov. Cuomo's briefings (by Aaron Carr, the author)

Dear fellow urbanites, city dwellers, and city lovers,

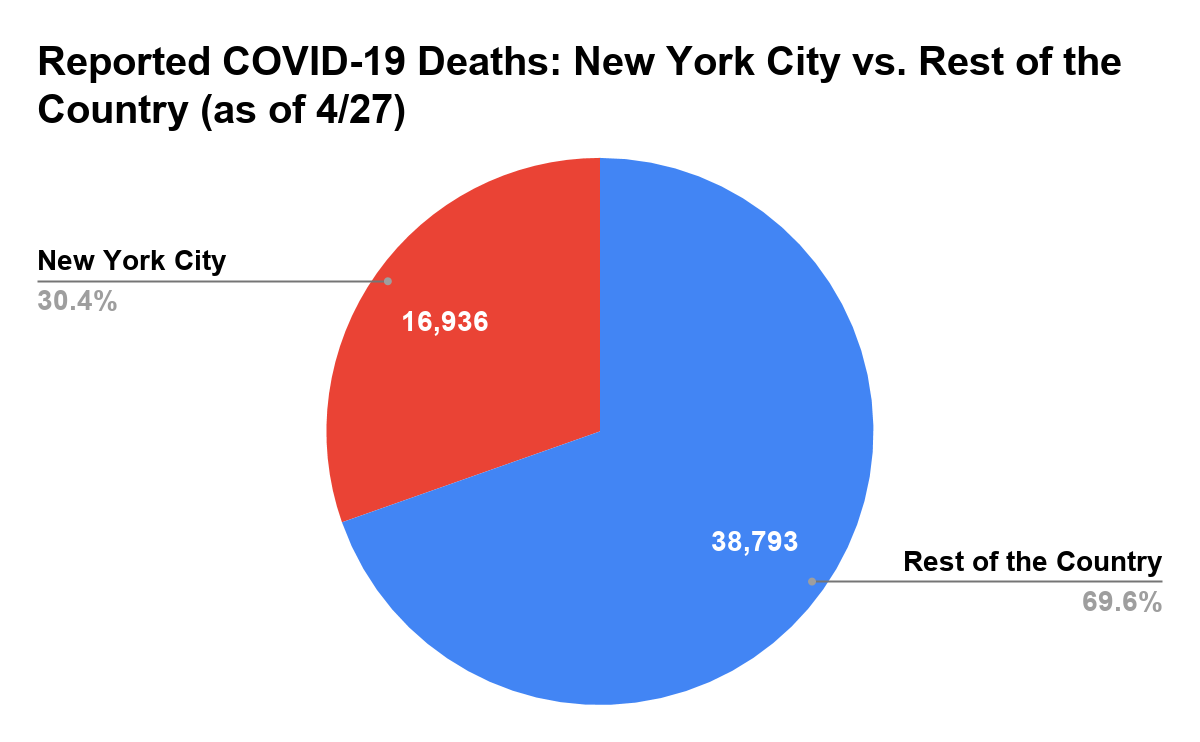

I regret to inform you that the heart and soul of New York City is under attack. And not just by COVID-19, which, as of April 27, has taken the lives of an astonishing 16,936 New York City residents, but by fictional statements made by our own governor, Andrew Cuomo, who has deceptively blamed the spread of this infectious, vicious, and deadly disease primarily on our city's population density.

The governor deserves commendation for often being a voice of reason in this crisis, but he deserves condemnation for failing to acknowledge his own mistakes and for attempting to distract from them by scapegoating.

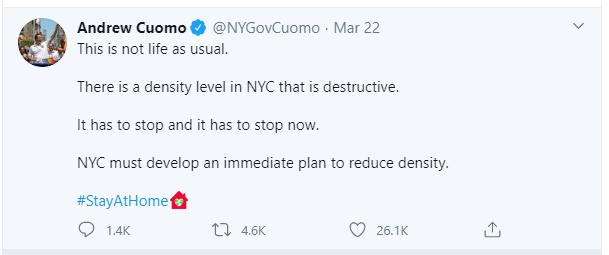

Before a national audience of millions, the governor accuses our city’s density of being “dangerous” and “destructive.” But he’s wrong. Density is not dangerous and destructive –– a failure to plan, a failure to prepare, and a failure to act early is what has allowed COVID-19 to wreak devastation on New York. (Unfortunately, Mayor de Blasio has also relied heavily on this argument)

It is certainly fair to ask, “Isn’t density a factor?” And of course density is a factor, it’s just not the factor, and in no, way, shape, or form the most important factor.

California, for example, has many densely populated cities, yet responded much quicker than New York to the novel coronavirus. Governor Gavin Newsom’s stay-at-home order (the first in the country) was implemented on March 19 when California had just 1,006 confirmed cases. Governor Cuomo, on the other hand, delayed implementing such a decision until March 22 when New York had a whopping 15,168 confirmed cases.

Just consider for a moment the millions of New Yorkers who likely came in contact with each other during those few days — going to work, walking on crowded sidewalks, riding a packed subway car, rubbing shoulders, coughing, touching common surfaces, and all the while transmitting this highly infectious and contagious disease.

In an interview with the New York Times, Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and former commissioner of the city’s Health Department, said “if the state and city had adopted widespread social-distancing measures a week or two earlier, including closing schools, stores and restaurants, then the estimated death toll from the outbreak might have been reduced by 50-80 percent.”

So, it should come as no surprise that, despite accounting for just 2.5% –– one-fortieth –– of America’s population, New York City represents nearly one-third of America’s COVID-19 fatalities.

Yet, instead of taking responsibility for his slow response, Governor Cuomo has launched a scapegoat campaign, blaming New York City’s natural identity -- our density -- as the source of the problem.

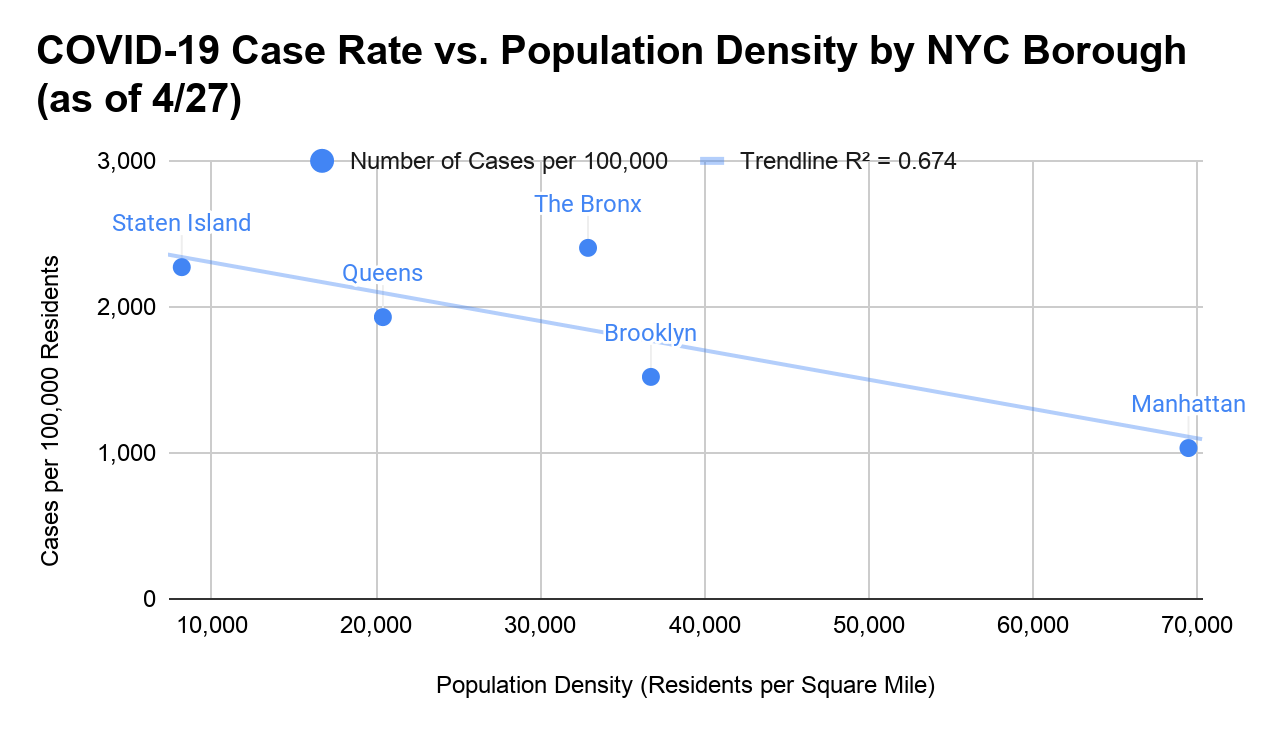

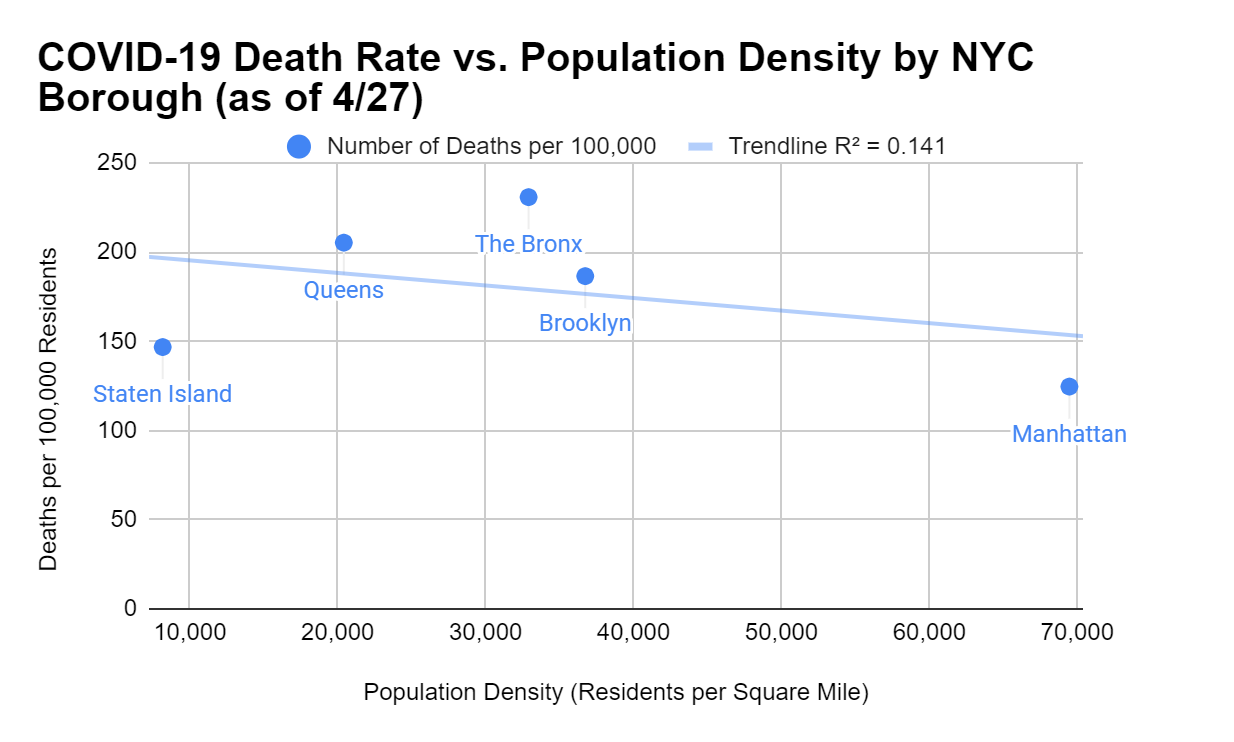

But the data, while correlational, strongly suggests that the governor is wrong:

If density is so destructive, there should be a strong positive correlation between the density of the five boroughs and number of COVID-19 fatalities and cases -- particularly in Manhattan, which is not just the densest part of New York City, but of America.

There isn’t.

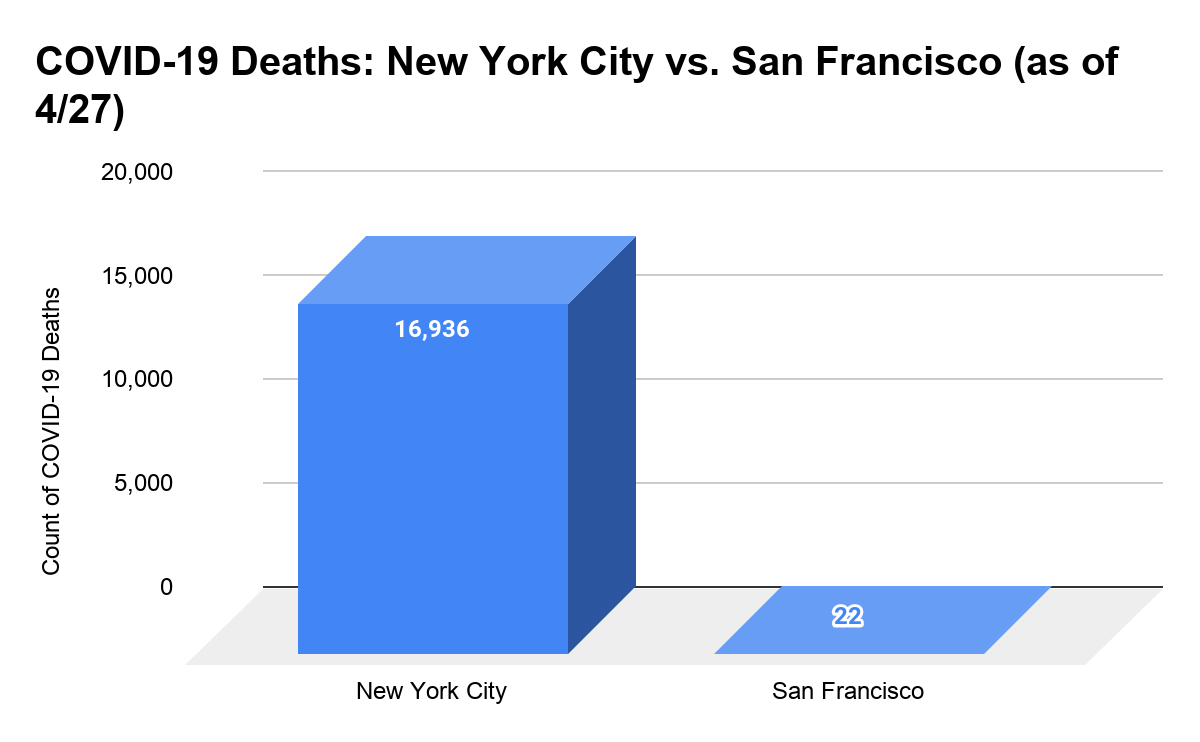

If density is so destructive, New York City should not have 770 times the fatalities of San Francisco -- the second-densest large city in the United States -- despite having only 10 times the population.

But we do.

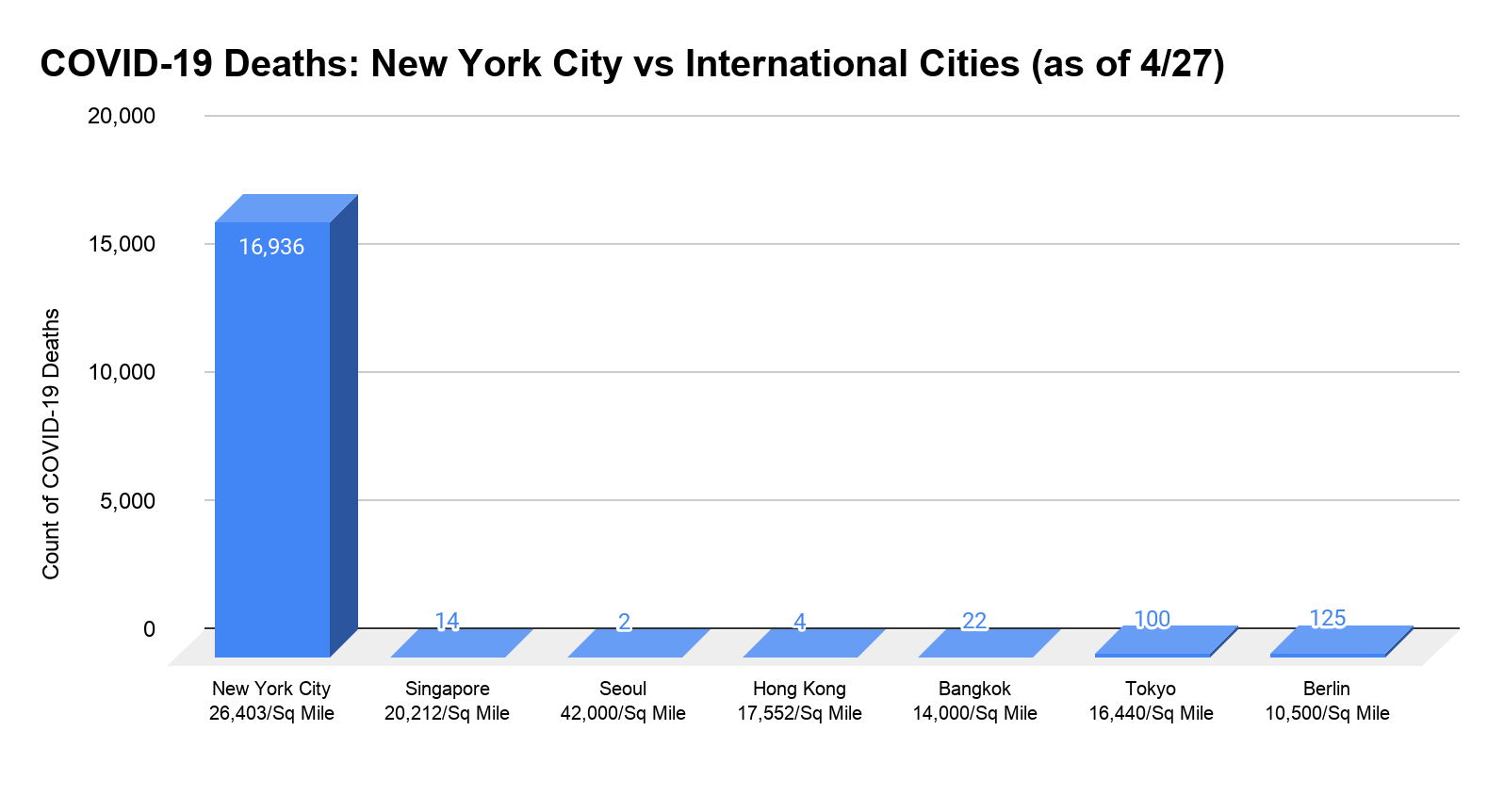

If density is so destructive, New York City should not have 1,210 times the fatalities of Singapore and 8,468 times the fatalities of Seoul (846,700% more), which is in close proximity to China, has a million more people, and is twice as dense as New York City.

But it does.

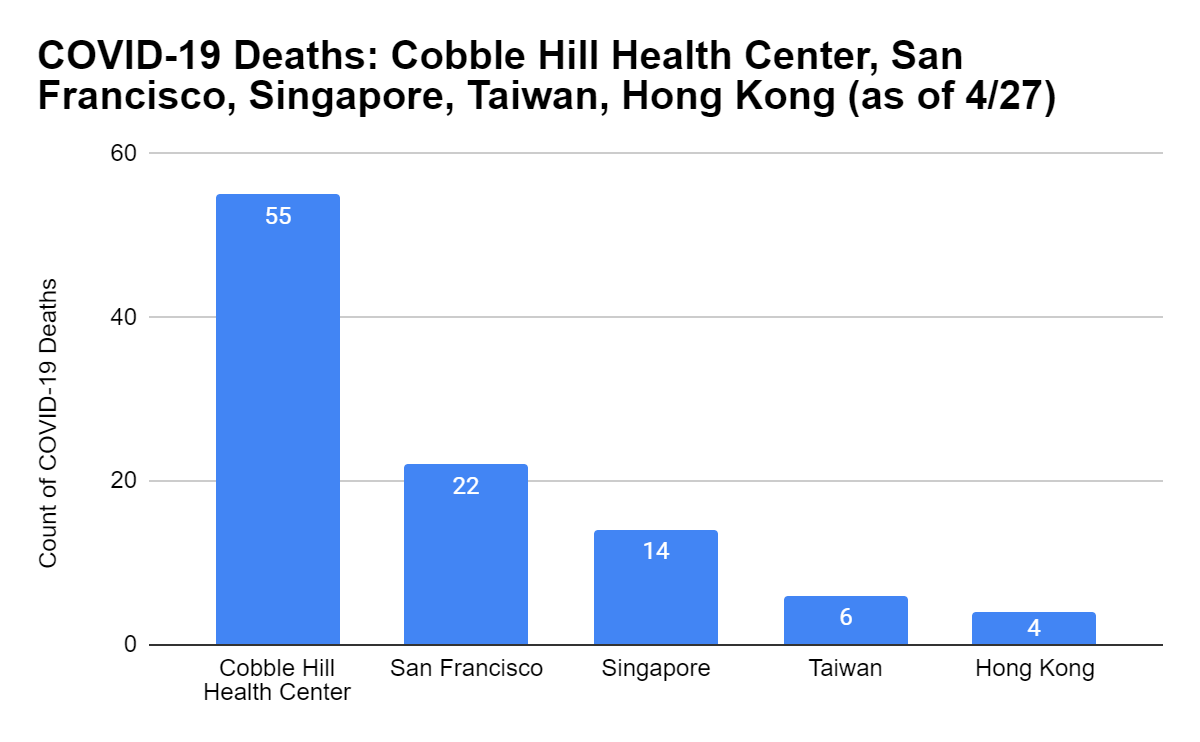

If density is so destructive, a single senior center in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, wouldn’t have had more deaths than entire cities and countries. But it has.

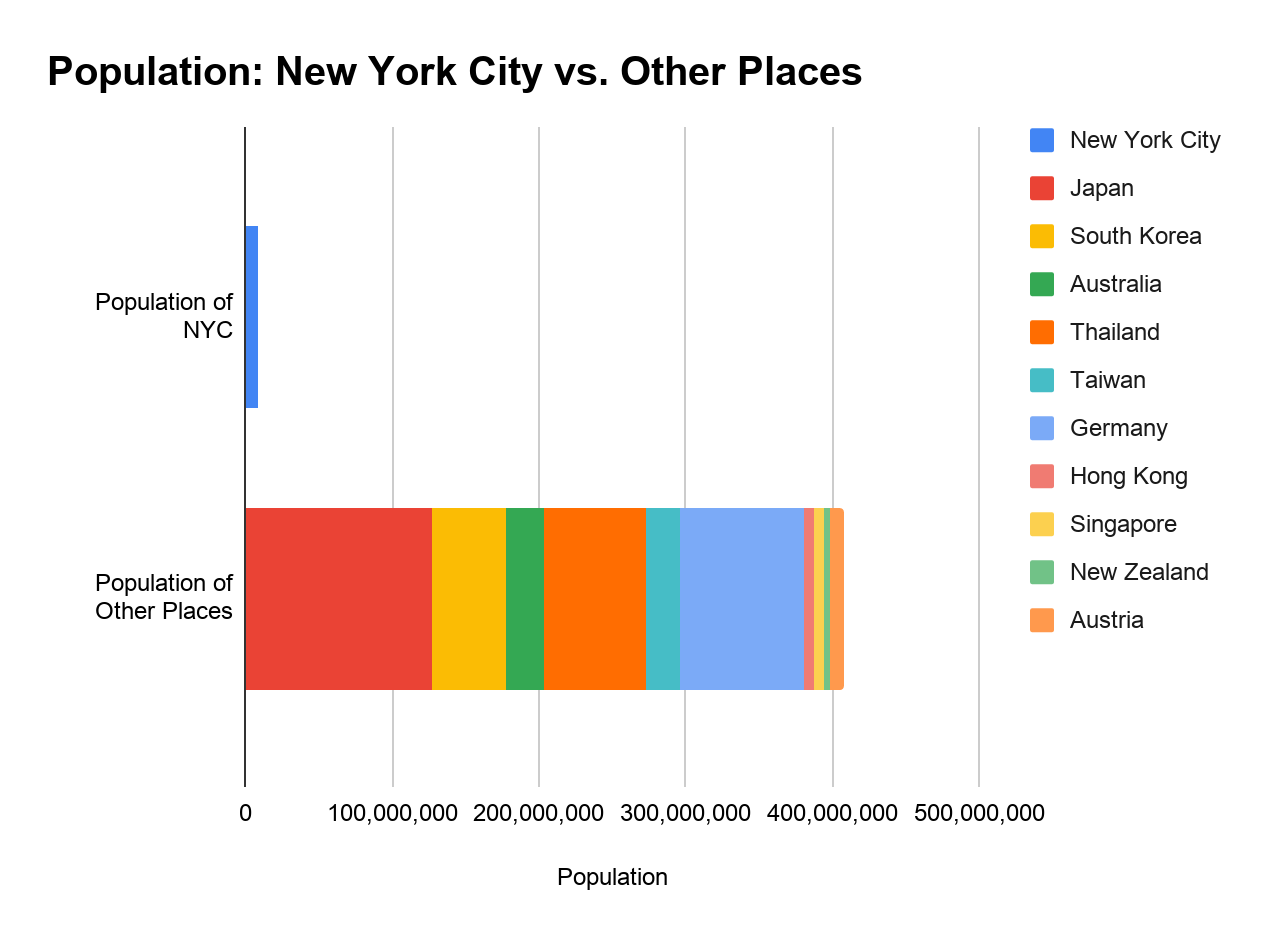

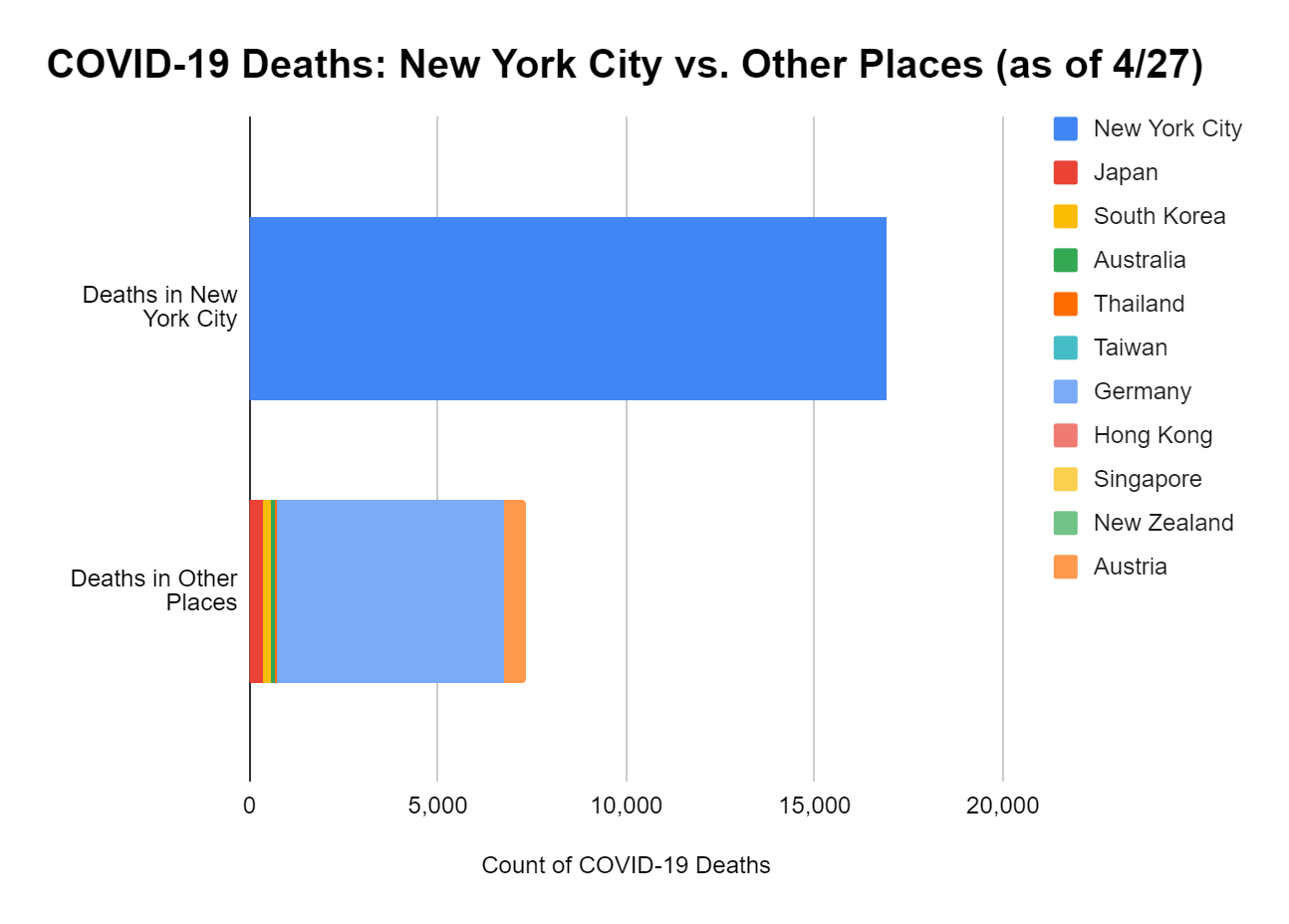

If density is so destructive, why does New York City have 9,621 more deaths than Japan, South Korea, Australia, Thailand, Taiwan, Germany, Hong Kong, Singapore, New Zealand, and Austria combined, while all these countries are home to dense cities and a total population of 400 million people.

Here’s the rub: Cuomo’s attack on density actually has little to do with density and everything to do with politics. Cuomo is a master politician, and like any master politician, he is a master of words. And, Cuomo -- always choreographed and calculated -- chooses his words with precision. In this case, by intentionally conflating the word “density” with “crowding,” which are two very different things. Density refers to the number of people per square mile of land. Crowding is when a large group of people convene together in a small space.

In a pandemic, it’s crowding -- not density -- that’s destiny.

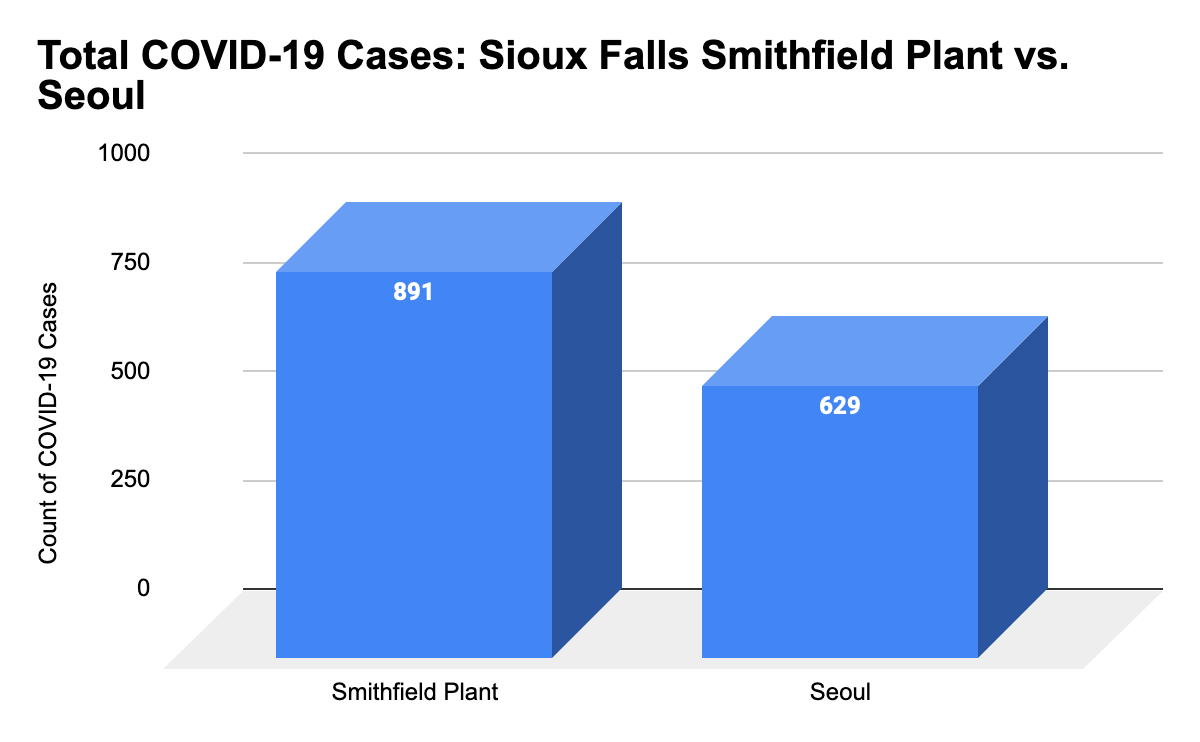

Take for instance, the Smithfield Foods pork plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. More cases have been linked to this one plant than all of Seoul, South Korea, a city with 9.7 million people, in a country that at one point had the second most COVID-19 cases in the world.

The problem at the Smithfield Plant wasn’t density, it was crowding. And the same rule applies to cities in general.

San Francisco, for example, did not become a model for the country by reducing density, but by reducing crowding -- through aggressive, decisive, early action.

The reason Cuomo is putting his eggs in the density basket is because, unlike crowding, he can’t control density and therefore he can’t be blamed for the outcome. But knowing that he could control crowding early, and didn’t, the question then becomes, “why did Cuomo delay?,” and that is the last question Cuomo wants to answer.

To be sure, the majority of the blame falls on the incompetence, ineptitude, and callousness of the Trump administration, for, among other things, ignoring multiple warnings from his intelligence agencies and failing to provide states like ours with the support so desperately needed. History will not be kind to the president.

But in our decentralized system, it is governors that have jurisdiction over stay-at-home orders and the power to enforce them. Furthermore, the scientific literature demonstrates that early social distancing can be crucial in combating infectious disease.

There is no doubt that Governor Cuomo deserves praise for the exceptional job he has done keeping the public at ease and our city, state, and nation informed. But if we are going to learn lessons from COVID-19 and be better prepared for the future, we need an honest assessment of what went wrong. One that leads to a simple question of why 16,936 people have died in New York City, when only 22 have died in San Francisco, 4 in Hong Kong, and 2 in Seoul, South Korea.

The answer is not density -- it’s planning, preparation, and early action.

***

Aaron Carr is Founder and Executive Director of Housing Rights Initiative. On Twitter @aaronAcarr.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.