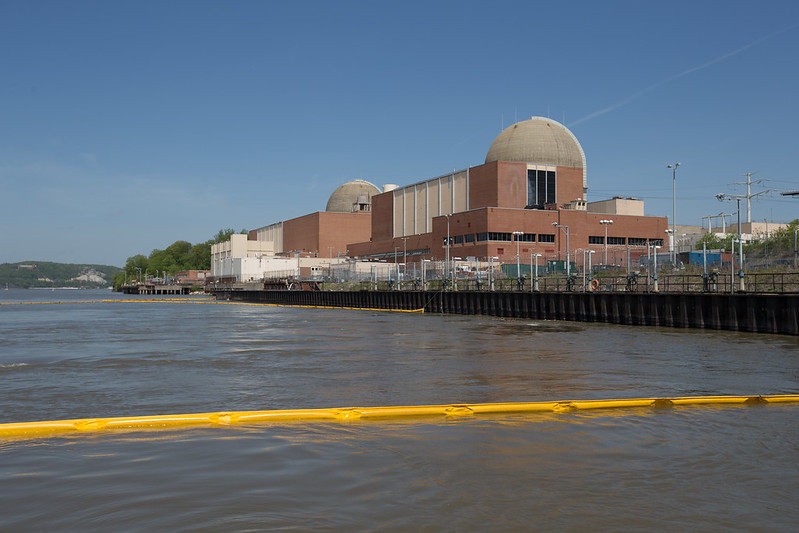

Letter to the Editor: Coronavirus Not Relevant to Needed Closure of Indian Point

Indian Point nuclear power plant (photo: governor's office)

In an opinion piece published April 7, several pro-nuclear energy advocates opportunistically attempt to link the imminent closure of Indian Point 2 with the region’s response to COVID-19, warning of potential blackouts if it closes. This cynical fear-mongering is wholly devoid of any factual support, impractical, runs contrary to law, and is the opposite of what we need right now, which is solutions-oriented forward thinking.

First, far from threatening blackouts, the current crisis has actually driven power demand in New York City down by 12%. In addition, study after study shows there is plenty of power without Indian Point and the grid will be as reliable as ever. The latest study by PSE Healthy Energy confirms that even without any new gas plants reliability would not be an issue. The same study shows that since the closure was announced in 2017, the state has added enough renewable energy and energy efficiency to replace Indian Point 2. In short, we have a public health crisis, but we do not have an energy crisis.

Second, in practice, Indian Point 2 is already shutting down, as its fuel rods run out of juice —- power is down by 18% and you'd need 18 months' lead time to refuel it. In addition, Entergy has requested approval of state and federal regulators to transfer the plant to a different owner for decommissioning. Even if we were experiencing an energy crisis, which we are not, Indian Point would not be the solution.

Finally, the closure agreement only allows the state to extend the operation of the plant if there is an emergency “by reason of war, terrorism, a sudden increase in the demand for electric energy, or a sudden shortage of electric energy or of facilities for the generation or transmission of electric energy.” Since none of these conditions exist, the closure agreement requires the plant to cease operations.

Indian Point is a safety risk due to aging, potential for earthquakes, and the impossibility of evacuation in case of an accident. Its outdated once-through cooling system also kills billions of aquatic organisms every year damaging the ecology of the Hudson River. Indian Point’s closure will create a safer metro area poised for new, more sustainable sources of energy and conservation that will put thousands to work. It will also lead to recovery of the Hudson’s ecosystem once its destructive cooling system ceases operation. Right now, we should all be focused on protecting the health and safety of our fellow New Yorkers, not getting sidetracked by those seeking to use the current crisis as a pretext to call into question sensible forward thinking decisions made years ago.

Sincerely,

Richard Webster

Legal Program Director, Riverkeeper

@EnviroWeb, @Riverkeeper

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

When Homeless New Yorkers are Safe, We’ll All Be Safer; The Mayor Must Use 30,000 Hotel Rooms Now

Homeless New Yorkers must be cared for amid the coronavirus (photo: mayor's office)

Last week we learned of Mayor de Blasio’s plan to move an additional 2,500 New Yorkers living in crowded shelters into hotel rooms by the end of April. While this may help some people escape the dangers of COVID-19, it simply does not meet the need.

For tens of thousands of homeless New Yorkers, virtually all of the protocols to prevent contracting and spreading coronavirus are impossible. Homeless people, by definition, cannot stay home, and many of the city’s 70,000-plus homeless people are living in settings that don’t allow them to easily wash their hands as frequently as needed or to shut a door and social distance from their neighbors.

If he really wants to make an impact, reduce the spread of coronavirus, and protect some of the city’s most vulnerable amid this crisis, Mayor de Blasio would utilize 30,000 of the 100,000-plus vacant hotel rooms across the city to move homeless New Yorkers out of the shelters and off the streets into spaces where they can easily practice social distancing, shower, use the bathroom, and wash their hands.

Further, the city already has a system and vendors for providing food to clients living in hotels, as it has long used commercial hotels as emergency shelters. And the mayor just announced enhanced efforts to deliver food to those who need it. The longer the mayor fails to act, the greater negative impact it will have on our whole city. Failing to act will lead to further spread of the virus and will continue to overwhelm the already overcrowded hospital system.

If homeless New Yorkers are safer, we are all safer!

Currently, over 19,000 homeless New Yorkers are living in congregate settings, where beds are often separated by less than six feet. Bathrooms and showers are shared by a large number of people. The food in the shelters is so notoriously awful that during the day, many people travel to soup kitchens or supermarkets to get nourishment. All of these factors lead to increased likelihood of contracting and spreading COVID-19.

Then, there are the thousands of New Yorkers who have stayed out of shelter due to the fear of violence within them and the knowledge of their own previous experiences with health and safety issues in shelter. Like their sheltered peers, they do not have access to personal protective equipment. With restaurants, recreation centers, and other public spaces closing their doors, unsheltered homeless New Yorkers have virtually nowhere to go to the bathroom, shower, or wash their hands. Some of our friends and neighbors have not showered since the city shut down.

On top of that, there is still the threat of NYPD “sweeps,” where people are only offered congregate, intake shelters as an alternative to moving from their spot. Despite CDC guidelines, the city continues to conduct such “sweeps,” which only serve to move people from place to place and make them even more vulnerable to contracting and spreading coronavirus.

Just as importantly, workers in shelters also face many of the same risks as shelter residents. The city has made lackluster efforts to provide personal protective equipment in the shelters, but it’s been made clear that homeless services staff and shelter residents are being left behind. Workers return home and are forced to put their families at risk, too.

As of April 15, the Department of Homeless Services is tracking 487 homeless New Yorkers who are positive with coronavirus, including 22 living in the streets; 131 shelters have had positive cases and 33 homeless New Yorkers have passed away. We estimate that the true scope of the damage is much higher, but the data is lower due to undertesting.

We need 30,000 single hotel rooms now and the mayor has the resources to do it. Other cities and states are using federal emergency funding to make happen.

Mayor de Blasio has already made significant missteps in his efforts to combat coronavirus, including delays. He has waited far too long to help the homeless, and by doing so, he is putting homeless people, the staff that work with them, and all New Yorkers who come into contact with them at risk.

He must act immediately to prevent further tragedy.

Finally, after this is all over, there is no going back to normal. During this crisis, we are seeing the human toll we caused by managing homelessness rather than ending it. Moving forward, every possible resource should be used to move people out of the hotel rooms into their own apartments rather than back to the shelters. That means, among other important steps, strengthening the CityFHEPS voucher by increasing it to fair market rate so people can actually find apartments on the market, utilizing all vacant supportive housing units for those eligible, and placing people into set-aside housing units for those leaving homelessness.

The city must put forth an urgent plan for housing homeless New Yorkers, now and into the future. As a city, we made the mistake of accepting homelessness as an everyday reality. We can never make that mistake again.

***

Peter Malvan is currently homeless. He is a Safety Net Activist, the Co-Chair of the Persons with Lived Experience Committee of the NYC Continuum of Care, and the Vice President of the Midnight Run. Josh Dean is the Executive Director of Human.nyc, an advocacy organization focusing on street homelessness.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Lessons from the Pandemic: Coronavirus Crashes a New York City History Course

City Hall (photo: Mayor's Office)

I usually start each session of my graduate seminar on the city with a question: “So did anything significant happen this past week that we should discuss?” This time, as I looked at 18 faces across a computer screen for the first time, it evoked a gasp.

My students and I won’t sit in a room together again as we did for weeks before, but we will continue to learn with and from each other. I think, teach, and write about New York. They are New York: diverse, smart, ambitious, striving to do better for themselves and for others. They are losing income; they are struggling to maintain some degree of normalcy. A few have done the unthinkable and moved back with their parents to gain space.

The course is a deep dive into the history and politics of New York, organized around the tenure of mayors from La Guardia through de Blasio. Little did I know when I conceived it that de Blasio’s reign might mark the end of New York as we knew it. We still don’t know what that means. Can we draw anything from the past to help us anticipate what lies ahead? If history does not provide us with answers, perhaps it can help ask the right questions.

I never liked the idea of remote learning. I saw it as a cost-cutting technique that would cheapen the educational experience. I still do. Now with no other choice, I have to admit that it enforces a sense of intimacy I had not expected. Now my students are in my home and I’m in theirs. Should I offer them a glass of wine or a wedge of cheese? We seem somehow closer, drawn together by the madness around us outside the safe space of the computer screen. We are in it together.

What can we learn? We had just completed a lesson on the city fiscal crisis of 1975. The vulnerabilities of the local economy exposed then are on display now as theaters and restaurants close, people are furloughed, the tourist industry has tanked, and Wall Street is in a panic. What exactly will the budget cuts look like? Who will suffer?

Last time it hurt those who need city services the most. We had seen how the 1975 crisis magnified the state’s power over the city as our current governor distinguished himself and moved to the center of the national stage. Even those wary of his governing style had to concede a hint of admiration. He was now the good bully who could stand up to the Twitter monster of Washington. Yet, a glimpse of his usual self was apparent when he and the Legislature buried an election law provision in the crisis budget that would make it more difficult for his Working Families Party opponents to get their progressive candidates on the ballot.

Our class already had covered the topic of suburbanization. Reading Ken Jackson’s history of how privileged 19th century families once built country homes to escape plague-ridden cities seemed quaint a few weeks earlier. Now it is suddenly relevant. Would the new pandemic serve as an equalizer between the rich and the poor? No, not a chance. Not in a city and country more economically polarized than ever. The poor and people of color are dying in larger numbers.

Will the coronavirus restructure the economy of New York? Clever corporate executives who need to recoup losses don’t need much imagination to see the experience as an experiment in remote labor that could cut the costs of Manhattan office space. What will be the long-term effect on commercial real estate if working at home becomes more common? If employees don’t regularly commute and set up shop in their living rooms instead, will they start to rethink life in those cramped city apartments? Will they respond more appreciatively to the beckoning call of open spaces in the outer reaches? What if flight from the city drives down the cost of residential real estate in the boroughs? Could that slow an outward migration?

Of course, the big question in our seminar is one I always thought I had the answer to. What is this creature we know as New York? Does it have a soul? If so, is it a kind and loving soul that takes care of the disadvantaged and the marginalized? Or is New York a harsh master that drives vulnerable people further into the ground? We examined the pre- and post-fiscal crisis city -- or should I say cities -- as a way to approach the question.

The former was a city of hope and promise that took us through the Great Depression and became a battleground for equality during the sixties. The other was a city obsessed with its own economic survival, retreating from its ambitious social agenda. As New York struggled through the latter more sobering chapter of its recent history, we observed how gentrification evolved: once sought as a source of fiscal regeneration, now understood as a byproduct of economic polarization.

Studying the past, we are reminded that New York was best-equipped to propel its progressive dreams when it had an enabling partner in Washington, D.C., epitomized by the leadership of Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson. More recently, with a White House devoid of capable or caring leadership, local leaders had convinced themselves that the next round of New York progressivism could be a bootstrap effort paid for by the proceeds of its own miraculous recovery. Today that recovery is at risk.

What will the future bring? It is too early in this bleak episode to say. For now, we can just keep educating ourselves and try to ask the right questions.

***

Joseph P. Viteritti is the Thomas Hunter Professor of Public Policy at Hunter College and author of The Pragmatist: Bill de Blasio’s Quest to Save the Soul of New York (Oxford).

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.