We Must Answer #MeToo with Comprehensive Sexuality Education

As a coalition of health educators, advocates, students, community service providers, and teachers, we know that the stories behind #MeToo are not new. For many of us, it is what led us to this work. Our own stories of assault, harassment, or discrimination, and the stories of the people we love drove us to want to create a better world for the next generation. So that women are not always asked what they were wearing, and so that LGBTQ youth are not told their true self and gender is ‘just a phase’ they’ll grow out of with conversion therapy.

We also know that “Time’s Up” for providing all young people with the tools and information they need to build healthy communities and relationships—and that New York City should be a leader when it comes to sexuality education.

The #MeToo movement has unearthed the extent to which sexual harassment, assault, and the devaluing of women, both cis and trans, pervades our society. No workplace or institution is free from these realities and we are just beginning to take a hard look at the societal systems in place that enable such continued abuse.

This reckoning is long overdue, but we are ready for it.

We are called now to ask ourselves what needs to change. What do we truly want to be different than it was?

Workplace accountability and equal pay, survivor protections to safely report abuse, better representation of women and people of color in positions of power. These are all urgent needs, and yet they don’t fully get to the root of what’s needed for a societal shift to meet the scale of the #MeToo movement.

If we are going to commit to the values of gender equity, trusting women, and enthusiastic consent, it’s going to take a lot of work and a lot of learning.

Luckily, we have an unprecedented opportunity in this current moment to invest in that learning. But we need to start from the ground up. We need to teach our young people from an early age how to identify and cultivate healthy relationships, how to ask for and give consent freely, and how to respect and love one’s own body and respect the bodies of others, with sensitivity to people’s backgrounds and experiences different from their own. These are not one-off conversations or hour-long school assemblies. This requires continual skills-building around communication, empathy, and inclusion, and for us to embed these lessons and tools in our educational system from day one through an interdisciplinary approach.

Truly comprehensive sexuality education requires that students learn about safe sexual practices and wellbeing, body autonomy and positivity, consent communication, anti-bullying measures and bystander intervention, where to access trusted confidential health care, how to navigate technology and social media in intimate relationships, and must include lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, transgender, and gender non-conforming students in each topic.

Comprehensive sexual health education also requires that these lessons be taught in all grades K-12, enabling schools to incorporate social and emotional learning skills and core values into the classroom from an early age and start with foundational lessons around respect and positive relationships that allow for more complex and critical discussions to be had later on.

The latest revelations of the #MeToo movement have shown us how ill-equipped we are in our understanding of consent and positive sexual behavior. We need to teach people of all genders how to engage in healthy relationships, and how to ask for consent, rather than putting the burden on one person to shout “no” loudly enough.

We know that comprehensive sex ed works; study after study has shown the positive health and emotional benefits sexuality education provides young people. But right now in New York City, it’s too little too late. According to the Department of Education’s own findings, almost half of last year’s graduated 8th-graders never received a semester of health in middle school, when lessons on sexual health are supposed to be taught. A recent report by New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer, and the creation of a Mayoral Task Force on sexual health education, highlight the extent to which this issue needs to be urgently addressed in New York.

At Sexuality Education Alliance of New York City, we’ve heard from teachers who have great models for sexual health education at their schools, and we know it’s possible. All students deserve comprehensive, inclusive, and skills-based sexual health education. And they deserve it at every grade and stage of life.

If we’re truly committed to addressing the ways our society enables a culture of discrimination and gender-based violence, and to saying #TimesUp, then we need to commit to large-scale educational change and do our part to honor the people who have come forward to share their stories. This is one of the biggest and most pervasive issues we’re facing today--no investment is too big to build the future we want.

***

Elizabeth Adams is the Co-Chair of the Sexuality Education Alliance of New York City and director of government relations at Planned Parenthood of New York City. On Twitter @ElizaBAdams.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Death of Bloomberg-Era School Roils East Harlem

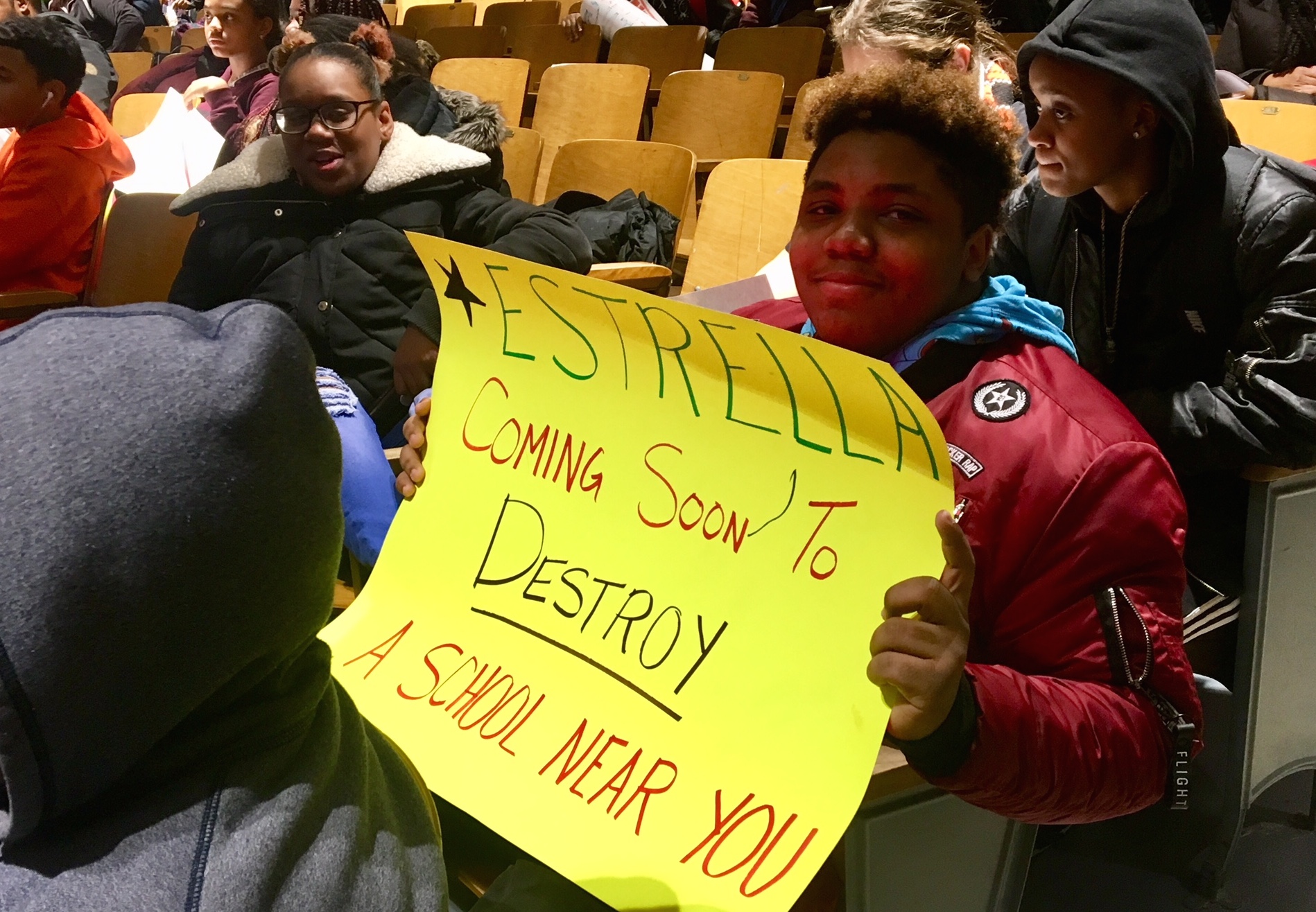

Protesting school closure (photo: Andrea Gabor)

Earlier this month, Kevin Medina, a high-school sophomore, stepped up to the microphone at a crowded public hearing to defend the East Harlem middle school that, he says, changed his life.

“I’m a Hispanic kid,” said Medina, who now attends Urban Assembly Gateway School for Technology. “I live with my grandmother, who is disabled and who is on welfare. We have nothing. But because of this school I may go to M.I.T. for free. Because of these teachers, who made sure we have everything we need.”

Medina was talking about Global Technology Preparatory, a public middle school that had introduced him to Google’s Code Next program, which is designed to recruit gifted black and Latino students into the tech industry. “Because of Global Tech, I know as much computer science as a college freshman or sophomore,” he added.

Medina was among dozens of alumni, parents, former teachers, and community members who came out, over the last two weeks, to offer testimonials for the small school that, they say, did big things for the poor kids of color in its charge. However, last week, at a contentious hearing of the Panel for Education Policy, which makes the final determination on proposed school closings and mergers across the city, the education department won approval for its plan to “merge” Global Tech with P.S. 7, a K-8 school. The two schools share a building on East 120th Street in East Harlem.

Global Tech, which was founded under Mayor Bloomberg, is one of the rare schools effectively being closed even though it is not failing; the reason given by the education department is that the two merged schools are both under-enrolled.

A one-to-one laptop school, Global Tech has consistently scored above its peers on standardized tests. It also has offered supports that have enabled a population of poor students of color, over one-third of whom had Individualized Education Plans (I.E.P.s), to attend some of the city’s best public schools. Most of its alums also have gone on to college.

“Consolidations are intended to improve under-enrolled schools and to address the budgetary and programmatic and performance challenges that arise as a result of low enrollment,” explained Josh Wallack, deputy chancellor at the Department of Education, at a joint public hearing held earlier this month in the P.S. 7 auditorium. “Students attending the consolidated P.S.7 will have access to a wider variety of academic and enrichment opportunities, interventions and other supports that would not be financially feasible for either of the individual schools to offer in the absence of a consolidation.”

That’s an argument current Global Tech parents and former teachers dispute. They say the merger was engineered at the end of the last school year, before required consultation with the community, and to the detriment of both schools. Last spring, Alexandra Estrella, the District 4 superintendent, forced out Global Tech’s principal, David Baiz. She also rejected every teacher-tenure application Baiz had approved. In the wake of Baiz’s departure, all but two of Global Tech’s 16 full-time faculty took jobs at other schools—though most returned for the hearings, sporting t-shirts inscribed “Greatness that Perseveres” and “GTP Forever.”

By the start of this school year, middle-school classes at the two schools were already co-mingled. The MacBooks once assigned to each Global Tech student are scattered throughout the building. Students with I.E.P.s are not receiving mandated services, according to several parents and former teachers who maintain contact with Global Tech families. While Global Tech’s after-school program is still offered by Citizen Schools, a nonprofit contracted by the city, it is no longer mandatory and few students attend. There have also been reports of “raging fights” and “chaos and disarray,” according to a broadly distributed email from Chrystina Russell, the school’s founding principal.

Estrella also replaced P.S. 7’s principal, Jackie Pryce-Harvey, who had helped found Global Tech. After Pryce-Harvey’s departure, some special programs there also disappeared. Indeed, at one point, Baiz and Pryce-Harvey had suggested merging P.S. 7’s middle school with Global Tech, under Baiz’s leadership; but the idea was rejected by Estrella.

“Respectfully, GTP never had a problem with resources,” said Ramona Gross at the joint public hearing on Global Tech. Gross credits the school and its programming for the fact that her son, William, who had an I.E.P., is now a freshman at Utica College.

“He came to Global Tech a small, quiet, scared, stuttering kid,” said Gross. “Global Tech taught him leadership” and self-confidence.

Current parents and students also say they are unhappy with the merger. Ysabel Martinez’s youngest son, Joseph, picked Global Tech because his brother Josniel had a wonderful experience at the school. Josniel, who had an I.E.P., represented Global Tech at a White House conference in 2011; he now attends York College, a four-year CUNY school, and aspires one day to become president.

The boys’ mother says, in Spanish: “I didn’t know about the changes. I didn’t know the principal had left, that it’s a different school.”

Joseph is not happy at the merged school, she adds, and they are now looking for a new school.

During her turn at the microphone, Shannon Meminger, a former Global Tech dean, reeled off well over a dozen partnership-based programs the school had offered, many of them anchored by a mandatory after-school program, itself a partnership with Boston-based Citizen Schools: the Apollo theater, Google, Little Kids Rock, as well as other arts- and science-oriented programs.

Yet, the one thing Global Tech has struggled with since its inception is enrollment. The school has never had more than about 175 students and enrollment has plunged during the recent year of turmoil to fewer than 130 students.

Neighborhood charter schools, which now educate one out of every four children in Harlem and cream students who do well on standardized tests—one reason public schools like Global Tech fill up with kids with I.E.P.s.—may contribute to the enrollment challenges. Private donations also allow charters to spend on advertising and recruiting families.

Others at the hearings blamed Bloomberg who built his new small-school strategy on closing failing schools. The problem with this theory is that Global Tech’s entrepreneurial approach to raising funds and forging partnerships, its dedicated educators—not a single teacher left during Baiz’s last year as principal—and relatively strong student performance, made it just the sort of small school the Bloomberg administration was inclined to protect.

Not so Carmen Fariña, the schools chancellor who will soon retire, and who has expressed her distrust of small schools and overseen 21 consolidations. “We don’t run schools as charities,” Fariña said during last week’s panel hearing. Nor did she respond to demands for an investigation of superintendent Estrella, whose actions at Global Tech, as well as other District 4 schools, including Central Park East 1 and Esperanza, have earned her censure and scorn.

“The school was shot, decimated by the superintendent,” says Isaac Carmignani, one of the members of the Panel for Education Policy appointed by Mayor de Blasio. “I spoke from the stage about my concern about what we heard. You don’t get 150 people speaking with one voice from all stakeholders.” Carmignani added that he voted for the merger because there is no going back for Global Tech. (The panel’s vote included six for merger, four abstentions and one recusal.)

Not everyone was moved by the testimony in favor of Global Tech. Servia Silva, the District 4 union representative, never spoke on behalf of the school. Neither Silva nor Estrella responded to interview requests.

Several participants expected a representative of the Manhattan Borough President to defend the school; the borough president, Gale Brewer, came to the meeting herself, but did not speak. Michael Kraft, a panel member appointed by Brewer, says she doesn’t try to influence his vote. Kraft, who said he knew nothing about Global Tech until a week or two ago, voted to abstain because he, too, agrees, “The school that gave those great supports is just not there anymore.”

There are two lessons from the unraveling of Global Tech: First, the process for getting meaningful community input before schools are closed or merged is broken. Second, the education bureaucracy that Mayor Bloomberg tried to dismantle is, under Mayor de Blasio, as strong as ever.

***

Andrea Gabor is the author of “After the Education Wars,” to be published by The New Press in June 2018, and Bloomberg Chair of Business Journalism at Baruch College/CUNY. On Twitter @aagabor.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

State Leaders Must Blunt Impact of Federal Tax Reform on New York Nonprofits and the People Who Rely on Us

(photo via The Governor's Office)

The recently passed federal tax law will deepen inequality and jeopardize the health and wellbeing of families and individuals across our state. This legislation penalizes New Yorkers by capping the state and local tax (SALT) deduction and will create deficits that are likely to result in catastrophic cuts to the programs they depend on. These tax “cuts” will drive up the national deficit, which will then be cynically used as a rationale for slashing investments in critical programs such as food assistance, public housing, and affordable healthcare.

Our state leaders must take action to ensure that we can weather this storm.

Federal aid accounts for one-third of the New York State budget and directly accounts for 8-10% of the New York City budget. The state is already facing a deficit that will be exacerbated by any federal cuts to state assistance or Medicaid spending. For example, homelessness is a major problem in our city and two-thirds of the New York City Housing Authority’s budget comes from federal aid. Cuts in aid to states would also have a significant impact on our children as 41% of the budget for the Administration for Children’s Services and 8% of the Department of Youth & Community Development funding comes from the federal government. Lack of funds at these agencies would impact foster care, adoption services, after-school programs, and Head Start. When direct aid is cut, families and individuals will rely even more heavily on nonprofit human services organizations. Our nonprofits deliver essential programs through contracts with city and state governments that support people through every stage of life, including early child education, elder care, shelter for people experiencing homelessness, job placement, and nutrition assistance. However, these government contracts rarely cover the full cost of providing services, which has resulted in a chronically underfunded sector.

At the same time, this federal legislation dis-incentivizes charitable giving.

Private fundraising has been an important (but insufficient) tool for filling the deficit that comes with government contracts. The tax bill raises the standard deduction, and with that increase many people will not itemize anymore, meaning that they will not see a tax benefit in making charitable donations. According to the Indiana University School of Philanthropy in a report commissioned by Independent Sector, 82 percent of charitable giving comes from people who itemize their tax return, and it is estimated that charitable giving will go down by about $13 billion.

Too many organizations are already at a breaking point. In New York City, 18% of nonprofit human services organizations are insolvent. This tax bill could push them over the edge at the exact moment when they are needed most. While we know this is a difficult budget year, given the deficit and uncertainty at the federal level, it is now more important than ever that we make sure our nonprofits are financially strong and resilient.

We are asking the state to make investments in our workforce and our infrastructure to ensure we are strong enough to continue serving communities well into the future. The underfunding of human services is not a new issue, but we need the Governor to lead in this area and 1) fund the minimum wage for human services workers contracted by the State, 2) continue the Nonprofit Capital Infrastructure Fund – a highly sought after grant program that assists nonprofits in making crucial improvements to their buildings and technology, and 3) fund a wage adjustment for a workforce that has gone without a salary increase in over eight years.

The Governor’s Executive Budget recognizes the federal threats to New York and includes an impressive agenda, which requires the close collaboration of human services providers across the state who are threatened not only by federal policies, but also by years of state policies and funding decisions that have jeopardized their ability to serve as anchors for their communities. Our organizations are dedicated to elevating the human potential of our families and communities, and we were gravely disappointed that some of our representatives did not act in the best interests of our state in passing this damaging tax legislation. However, New York now has an opportunity to be a progressive leader for the country by making investments in the human services sector. In times of challenge and uncertainty, nonprofits are our communities’ first line of defense and careful planning and adequate financial resources from the city and state are needed to protect these essential services.

***

Center for New York City Affairs

Fiscal Policy Institute

FPWA

Human Services Council of New York

United Neighborhood Houses

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Note: this column has been updated to correctly identify Independent Sector as the funder of the Indiana University study, not the United Way as originally written.