A More Transparent City, with A Page for Every Capital Project

Construction in Corona Plaza (photo via DOT)

Few things impact the lives of New Yorkers more than the city’s “capital projects.” These projects create, maintain, and improve the infrastructure New Yorkers use every day, including: streets, bridges, tunnels, sewers, parks, and so much more. In 2018, the capital budget will be $16.2 billion, approximately 17% the size of the city’s $85.2 billion “expense budget.” What are these projects? How can you find out about them? It’s not easy, but it should be.

The Capital Budgeting process is a complex endeavour. The City maintains a 10 Year Capital Strategy that it updates every two years, and an Annual Capital Budget that is passed every year by the City Council, and a Capital Commitment Plan that is prepared by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) three times a year, which outlines precisely how and when funds are being allocated to agencies on a project by project basis. The Commitment Plan is the most interesting because it’s the closest to the reality of how the city is planning to spend our money. It comes in four “volumes” of PDFs containing 2,162 pages of table after table of information describing nearly 10,000 different projects. Printing this out results in a stack of paper about one foot tall.

In 2017, why isn’t all this information in an easy-to-use spreadsheet or database? The only reasonable answer is that the city doesn’t want the public to scrutinize this information too deeply.

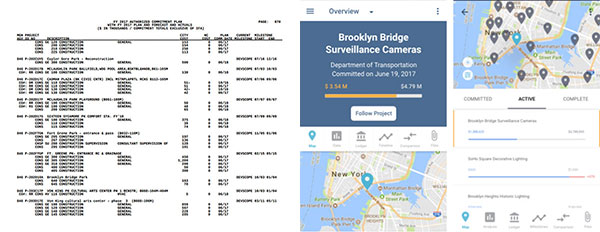

Fortunately, recent advances in technology have made it much easier to turn PDFs into spreadsheets, and spreadsheets into web applications. And that’s what I’ve done at projects.votedevin.com, where you can now find a web page for every single capital project, organized by agency and sortable by project’s cost. Of course, our ability to display useful information about projects is limited by the information in the capital budget reports - but there’s more than enough information to pique any budget conscious New Yorker’s interest.

Here’s an example: Project HBMA23216 from the DOT is a $312 million construction project for the “Promenade over FDR E81st - 90th St Bin 2232167.” That’s a lot of money for a promenade. By Googling the project’s name, description, and various internal codes (FMS Number, Budgetline and Commitment Codes) we can find a lot more information, like the RFP Notice, proposed architectural plans, and more.

As you browse the budget, sorting the most expensive projects by agency, more questions arise: Why does the City’s 311 system need a “Re-Architecture” that costs over $20 million this year? Why isn’t the press reporting the over $120 million in renovations planned for the Brooklyn Detention Center (search BKDC)? Why does the “Vision Zero Street Reconstuction” [sic] go from $2 million in 2018 to $100 million per year in 2021-2023?

I’m sure good answers exist for these and other, more probing, questions. These projects are, after all, funded by us taxpayers. Making this information more accessible would not only create more opportunities for civic engagement, it would also allow the public, journalists, academics, and others to serve as watchdogs, which might result in millions of dollars of identifiable cost savings.

A quick trip to the New York City Charter reveals that the City is required by law to document its capital projects in a very specific way. Presumably the City follows its Charter, which means this information exists, so shouldn’t the city share more of it? Cost shouldn’t be the reason we don’t have access to this information. If the City spent just 1/100th of 1% of the capital budget on public documentation, they could easily fund an exceptional website with a team of data organizers and content publishers who could keep it up-to-date.

What would that website look like? It would certainly have a lot more information than what the city currently publishes in its PDFs and on their “Capital Project Dashboard,” which offers very little additional information about the 189 “active projects over $25 millions.”

Imagine if the City maintained a web page for every capital project that contained all related public information: project status, project scope summaries, location on a map, lists of hired contractors and their fees, and an activity log so we, the people, could watch as projects move through their various stages. Now that’s the types of transparency we should expect from our city government!

Who has the power to make this information public? Certainly the Mayor's Office, but it's easy to see why it doesn't. The Mayor is responsible for directing the people and agencies leading these projects, so creating more avenues for additional scrutiny, which could easily lead to bad press, is hardly a priority. Fortunately, New York City’s Public Advocate, which is an entirely independent office, has some statutory jurisdiction within the Capital Budget process and could force the city to better document the capital budget.

Section 216 of the New York City Charter states, “Upon the adoption of any such amendment by the council, it shall be certified by the mayor, the public advocate and the city clerk, and the capital budget shall be amended accordingly.” While I’m not a lawyer, it sounds like the Public Advocate could threaten to stop certifying amendments to the budget until the city releases a database of all capital projects with additional information to help New Yorkers better understand how their tax dollars are being spent.

That’s precisely what the Public Advocate should do, and as a candidate running for that position, I commit to making that demand when elected. It’s up to you, the public and the media, to ask other Public Advocate candidates how they’d use their oversight power over the Capital Budget. Will they also pledge to demand "A Page for Every Project"?

Until the city offers a page for every capital project, I’ll will keep updating projects.votedevin.com so New Yorkers can learn more about what the city does with our money. It’s a tough job but somebody’s gotta do it.

(image of the city's capital commitment plan vs. our website)

…

Devin Balkind is a candidate for New York City Public Advocate. He is also the President of the Sahana Software Foundation, a nonprofit organization that produces the world’s most popular open source software platform for disaster management. On Twitter @DevinBalkind.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Where Mayor De Blasio Must Take Vision Zero Next

Mayor de Blasio and Vision Zero (photo via DOT)

Vision Zero is a singularly successful legacy project for Mayor Bill de Blasio. It would be more successful if his safety projects were decoupled from parochial interests.

In 2011, Transportation Alternatives and the Drum Major Institute published Vision Zero: How Safer Streets in New York City Can Save More Than 100 Lives a Year, the first Vision Zero report in the United States. In 2013, thanks to that report and assiduous follow-up advocacy by the victims’ group Families for Safe Streets, candidate de Blasio adopted Vision Zero as a key campaign promise, pledging to eliminate traffic fatalities by 2024. Many saw this as an impossible goal, especially after the impressive safety strides made during Mayor Bloomberg’s three terms in office. How much further could traffic fatalities really decline?

Mayor de Blasio officially launched Vision Zero at PS 54 in Woodside Queens on January 15, 2014, just two weeks into his term. Since then, traffic fatalities in New York City have declined 23%.

Whereas 290 used to die annually in New York City traffic crashes, today that number is about 240. It is difficult to overstate the significance of this success. If the pre-Vision Zero average annual traffic death rate had continued over the past four years, 122 more New Yorkers would be dead today and many thousands more would have been seriously injured. Considering that nationwide traffic deaths are up 17% over this same four-year period, the mayor’s effort is even more impressive. If New York City’s Vision Zero program were a vaccine, it would be heralded as a miracle drug.

What is more remarkable is how little the streets have changed to achieve this massive reduction. While the Mayor has championed transformative redesigns of many notoriously dangerous streets, the vast majority of known dangerous streets have yet to be affected by the DOT’s modern menu of traffic safety fixes such as pedestrian friendly traffic signal timing and protected bike lanes.

Queens Boulevard, the former “Boulevard of Death,” which used to kill a dozen New Yorkers every year, has not seen a single fatality in the past two years since being redesigned. Yet there is a backlog of more than 150 dangerously-designed streets and nearly 300 intersections that still need fixing. This long list of dangerous streets, outlined in the DOT’s own Vision Zero Pedestrian Safety Action Plans, represents an opportunity to save hundreds more lives. If Mayor de Blasio is re-elected, clearing this backlog of known-dangerous streets should be his first priority.

To help clear this backlog, the mayor recently increased the Department of Transportation’s budget by $1.6 billion. The problem is this: while the agency shows remarkable results at calming traffic and reducing crashes on any given street, it is moving at a snail’s pace to complete those projects. Now that his agency has the money, Mayor de Blasio must empower the DOT to deliver safety projects much more quickly and insist that it happens.

Today it takes a minimum of three years for the DOT to turn a dangerous highway-like city street into one that is designed for safe walking, cycling, and driving. Actually redesigning and repaving a street can happen in as little as a few months. Most of that three years is taken up walking on eggshells; the DOT attempts to anticipate and placate every parochial concern, as though safety infrastructure were a hot-button issue, and not a life-or-death public health concern. We’ve seen simple safety projects take years longer than they should, like the protected bike lane on 5th Avenue in Manhattan, which the community first requested in 2013, or get watered down to be less safe, like with Woodhaven Blvd., or get tied into petty power-brokering, like on 111th Street in Queens.

Before Vision Zero safety projects were proven life-savers, Mayor de Blasio could be forgiven for his timidity. Now, with the data strong and getting stronger (see Manhattan Institute’s recent report Vision Zero and Traffic Safety) it is time for the administration to elevate these projects to the urgent public health imperatives that they are. This means giving DOT freer reign to complete safety projects more quickly and break a few eggs, or rather break the hearts of a few petty power-brokers who care more about parking than people.

To further reduce preventable death on our streets, the mayor should also reconsider his opposition to congestion pricing.

More than just a way to fund transit and thin traffic so buses can move, congestion pricing is an effective safety tool. With fewer traffic jams, there can be more space for expanded safe pedestrian space and bike lanes. After congestion pricing was implemented in London, traffic crashes declined by 40%. A similar reduction in the proposed pricing zone in Manhattan would save dozens of lives per year.

And, as Mayor de Blasio doubles down on data-driven traffic-safety policies that work, he should cease those that do not. Every officer tasked with outfitting senior citizens’ canes with reflective tape or writing tickets to cyclists is one less officer assigned to rein in reckless drivers, who kill pedestrians hundreds of times more often than reckless cyclists do. (In fact, a cyclist has not killed a pedestrian since 2014.)

Targeting cyclists and pedestrians in the name of Vision Zero may placate some vocal complainers but it does nothing to make streets safer. In fact, evidence shows the opposite: the more walkers and bikers are harassed the less safe we all are -- bikers bike less, for example. It’s the opposite of the “safety in numbers” effect, well-documented by researchers, showing that the more people there are on the streets, the more motorists habitually exercise caution and care, even if they are a little bit annoyed. The only way to improve bicyclist and pedestrian behavior that has been proven to work is to build better, safer infrastructure.

Vision Zero is not “traffic safety as usual.” Rather, Vision Zero says that protecting human life is more important than preserving parking spaces or speeding drivers. It’s time for Mayor de Blasio to make this principle the rule, not the exception, and empower his agencies to manage traffic and deliver safety projects accordingly.

If Mayor de Blasio is re-elected, and launches his second term by doing what I’ve laid out here, he will save at least 100 more lives per year. He will be a hero. Nothing else that Mayor de Blasio did in his first term has gained him as much national recognition as Vision Zero, as dozens of cities are following in New York’s footsteps. It’s time for him to show the city, and the nation, the way forward again.

***

Paul Steely White is executive director of Transportation Alternatives. On Twitter @PSteely & @TransAlt.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Why is Governor Cuomo Returning Weinstein’s Money But Keeping Loeb’s?

Gov. Cuomo (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

New York’s political world was rocked recently by revelations that Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, a major donor to Governor Andrew Cuomo and other top New York Democrats, had a long and sordid history of predatory sexual harassment -- and possibly sexual assault -- of women.

Initially Gov. Cuomo balked at giving back the $111,400 in contributions he had received from Weinstein. But a few days later, after Mayor Bill de Blasio called on all elected officials to return Weinstein’s money and the New York State Republican Party called out Cuomo, the governor saw the wiser route and decided to donate Weinstein’s tainted cash to a to-be-named women’s organization.

Sexism is deplorable and should not be tolerated, and it certainly should not play any role in our political system. Gov. Cuomo did the right thing by reversing course and shedding Weinstein’s money. It sends a strong message that he will not sanction Weinstein’s behavior, and it is a message to all political donors that sexism will not be tolerated.

However, we are confused. While Gov. Cuomo is sending a clear message that sexism is unacceptable, he has refused to send the same message about racism. Recently Daniel Loeb, a hedge fund manager and investor in privately-run charter schools who has given Cuomo $170,000, continued a pattern of behavior with an outrageously racist Facebook post. Loeb asserted that State Senate Democratic Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, the highest ranking African-American female elected official in New York State history, had done “more damage to people of color than anyone who has ever donned a hood” -- an unmistakable reference comparing Stewart-Cousins to the Ku Klux Klan.

Loeb’s racism doesn’t stop there. In 2006 Loeb also called Prem Watsa, a Canadian corporate leader who is of Indian descent, a “shvartze,” a Yiddish term for African-American that equates to the n-word. Loeb has also sought to profit off of Puerto Rico’s debt and drive up prescription drug prices. And as board chair of Success Academy, he has supported excessively punitive and rigid disciplinary practices and suspensions meant to force struggling African-American and Latino students out of Success schools. Such zero tolerance behavioral policies have been shown to put students on track for the school-to-prison pipeline.

Despite Loeb’s documented history of racism and support of racist policies, Gov. Cuomo refuses to return campaign contributions from the wealthy financier. In contrast, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer immediately shed a $4,500 contribution he had received from Loeb once the recent Facebook post became public.

Regarding the Weinstein incident, Gov. Cuomo stated, "I have three daughters. I want to make sure that at the end of the day, this world is a safer, better world for my three daughters." We wholeheartedly agree with that, but African-Americans and other people of color have daughters and sons as well, and they merit protection from racists like Daniel Loeb, who clearly showed his belief that he is superior to Senator Stewart-Cousins and that he knows what is better for children of color than she does. In New York State we will not accept a double standard under which sexist political donors are treated as toxic in political circles, but money from racist political donors is condoned.

Sadly, we are living in a time when the president has made racism a mantra and has emboldened violent white supremacists to openly assault opponents of racism. We applaud Gov. Cuomo for making clear that Harvey Weinstein’s sexist money is unwelcome in New York politics. Gov. Cuomo’s hesitation to return Loeb’s tainted money is deeply concerning and offensive. We need him to forcefully and definitively repudiate Daniel Loeb’s racism. No more excuses, it is time for the governor to give back Loeb’s contributions, like he’s doing with Weinstein’s.

Gov. Cuomo recently described racism as “the greatest threat this country faces” - so there should be no problem treating racism with the same firm hand as sexism. If the governor decides to keep Loeb’s money, he is sanctioning racism, just as returning Weinstein’s money was a clear repudiation of sexism.

***

by Zakiyah Ansari and Carmen Perez. Ansari is advocacy director for the Alliance for Quality Education and Perez is executive director of Gathering for Justice and co-chair of the Women’s March.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.