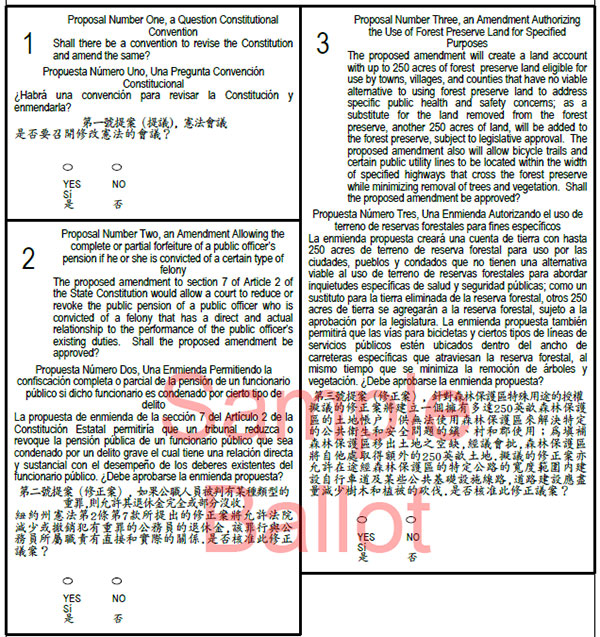

New York’s Con Con Ballot is Biased

(sample ballot excerpt - image via NYC Board of Elections)

When New Yorkers vote on Nov. 7 on whether to call a state constitutional convention, the question they will see on the ballot is: “Shall there be a convention to revise the constitution and amend the same?” This ballot text is the only form of convention related media that every voter will see immediately before voting—and when many voters are most impressionable.

Unfortunately, this seemingly innocuous question is highly biased because it doesn’t specify whether it refers to the federal or New York state constitution. Close to 100% of New Yorkers know they have a national constitution, but less than half know they have a state constitution. Thus, millions of New Yorkers may go to the polls assuming that what is being referred to is the United States Constitution. And since Americans are taught to revere their federal constitution like the bible, the question could just as well have been worded: ‘Shall the Bible, written by god, be rewritten?”

In short, the ballot language is strongly biased against a “yes” vote.

In 1846, when this language was first inserted into New York’s Constitution, it wasn’t biased in the same sense that it wasn’t then biased to refer to voters as white males. Only since the Civil War, with the growing chasm between knowledge of the federal and New York state constitutions, did it become biased.

Prior to the Civil War and the passage of the 14th Amendment to the federal constitution (which extended federal rights protections to the states), states played a much greater role in American government. The pre-Civil War era was one of state rights, state power, and state glory. The federal government was often subservient to state government, provided far fewer services, and was even often viewed by some politicians as a stepping stone to serving in state government. Since the state and national constitutions were largely co-equal, students studied both. State constitutional reform was also often in the news, partly because New York’s constitution had been the subject of high-profile revision during every middle-aged adult’s lifetime (e.g., conventions in 1777, 1801, 1821, and 1846), something that wasn’t true of the federal constitution. Between 1803 and 1865 there were no federal constitutional amendments, let alone high profile conventions.

Today, in contrast, New York’s constitution is often treated as a ragamuffin. Those who attend New York’s K-12 schools, visit its leading museums, and watch its history on TV, will rarely if ever be told that New York even has a constitution, let alone what’s in it or how New York’s nine state constitutional conventions shaped it. In contrast, the federal constitution has retained and even raised its position atop its Bible-like pedestal.

To be fair, by the time most voters enter the voting booth on Nov. 7, they will know they have a state constitution. The ballot abstract provided by the New York State Board of Elections does explicitly refer to the constitution as a “State Constitution.” But the fraction of voters who read the abstract will be exposed to an arguably even worse type of bias. For the abstract describes only the cost of a convention; nowhere does it describe any benefits. Thus, a rational person who reads this description would infer that a convention only involves costs—which mimics the message being promoted by legislative leaders and others who are leading the campaign to oppose a “yes” vote.

Instead of focusing on a convention’s costs and other procedural details, the ballot abstract should explain the convention’s democratic purpose in the context of the constitution. This would include explaining why New York’s framers provided for two methods of constitutional amendment, why New York courts have ruled that calling a convention is an inalienable right of the people, and why New York’s constitution (Article XIX, §3) specifies that when there are two conflicting amendments ratified by the people, the convention-proposed one trumps the legislature-proposed one.

This year Evan Davis, a leading advocate for calling a convention and former Counsel to Governor Mario Cuomo, sued New York State’s Board of Elections regarding its placement of the convention referendum question on the ballot. The suit’s admirable goal was to have the question more prominently placed on the ballot. This would signal its importance to voters and thus encourage them to vote on it. The remedy sought, which the court denied, was to have the ballot question placed on the front side of the ballot, where voters choose candidates.

A better proposed remedy, which would have avoided forcing judges to decide on the relative importance of candidate versus referendum questions, would have been to place the two different categories of questions on different ballots. This remedy would have treated candidate and convention questions equally, and it is used by legislators in other states when they want to discourage voters from leaving a legislature-initiated constitutional amendment question blank.

On the other hand, since the convention question embodies New Yorkers’ most fundamental of all democratic rights—the people’s right to constitutional reform—it should arguably be given the most high-profile ballot position. Many states have granted it that position by calling a special election, but that remedy is both undesirable (e.g., it reduces turnout) and illegal (New York’s constitution specifies that the convention referendum be held at a general election).

My own preferred approach would be to eliminate government control over ballot media—a power that government officials routinely abuse despite claiming to practice objective ballot journalism. But as I argued in a prior column, New York currently lacks the election infrastructure to make this reform viable. Fixing that antediluvian infrastructure should be a priority for any convention the voters approve.

With only days to go before the election, the press should educate the public on the most basic constitutional and convention facts that New York’s public and non-profit educational institutions have shamefully failed to teach.

First, a New York state constitution exists, and the convention referendum refers to it.

Second, the New York constitution greatly differs from the federal constitution. It is about seven times as long (about 8,000 versus 55,000 words); full of provisions made obsolete by new federal laws; pockmarked with hundreds of legislatively-passed amendments that make the document incoherent and unreadable; and shunned by New York’s most prestigious educational institutions, including schools and museums, as unworthy of their educational efforts.

Third, the framers of New York’s convention process believed that it had not only costs but great benefits, as it is New York’s only available mechanism to bypass the Legislature’s gatekeeping power over constitutional amendment—an essential component of New Yorkers’ right of constitutional reform.

Fourth, the question’s obscure placement on the ballot should only signal incumbent state officials’ political self-interest, not the question’s importance as a safeguard of a vital democratic right--the people’s right to alter their constitution in the face of a legislature’s opposition. There is no more important question on the ballot, as signaled by the many millions of dollars New York’s most powerful legislative lobbying groups are spending to defeat it.

Addendum: Readers, including Karen Biesanz from the League of Women Voters, and Evan Davis from the Committee for a Constitutional Convention, have pointed out to me that the wording of the ballot question also misleadingly implies that a convention will not only propose but ratify amendments. In Ms. Biesanz’s words, it “implies that there WILL be revisions/amendments” despite a convention’s proposals not being “a done deal till the electorate votes to accept [them].” They have made an excellent point. The ballot’s wording bolsters the opposition’s strategy of implying that the people lack the power to vote a convention’s proposals up or down; it should have clarified that the people retain a veto power over any convention proposed constitutional reforms.

***

J.H. Snider is the author of "Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other U.S. States 1776-2015" and editor of The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Vote ‘Yes’ on Question 2 and Send Albany a Message

(photo: Edwin J. Torres/NYC Mayor's Office)

This Election Day, New Yorkers have an opportunity to vote for ethics in government. You won’t see the words “anti-corruption” or “integrity” on the ballot, but make no mistake – these essential elements of trust in government are at the core of Ballot Proposal 2, which will be put before voters on November 7.

Proposal 2 -- which can be found on the back of your ballot with two other questions -- seeks the public’s approval to amend our state constitution to “allow a court to reduce or revoke the public pension of a public officer who is convicted of a felony that has a direct and actual relationship to the performance of the public officer’s existing duties.”

If a majority of New Yorkers vote “yes” on Proposal 2, no longer will pension dollars automatically go to felons sitting in jail who have thoroughly violated their oaths of office. For crimes committed after the enactment of the constitutional amendment, not only would taxpayer money be saved, but also the message would go out that the Empire State no longer tolerates – and bankrolls – corruption.

When I proposed a pension forfeiture constitutional amendment during my first year in the State Assembly, 2013, I was told there was no chance of this idea passing in Albany. Criminal conduct among elected officials was all too common. Many ethics reforms had gone nowhere in our state capitol. The State Assembly was led by Sheldon Silver and the State Senate headed by Dean Skelos, two men who would be forced from office after being embroiled in corruption scandals. But broad backing from the citizens of New York helped this idea overcome many hurdles, leading to the 2016 and early 2017 legislative passage of this proposed constitutional amendment, which placed the measure on this November’s ballot.

A vote in favor of Proposal 2 would send a clear message to state officials that we no longer tolerate corruption, forewarning them of what is to come if they violate the public trust they’ve sworn to uphold. Proposal 2 empowers voters to respond by putting ethics reform directly in our state constitution. (Don’t confuse this vote with the vote on Proposal 1, which asks whether New York State should hold a constitutional convention – a convention would likely deal with many other topics beyond ethics reform.)

If voters overwhelmingly support the pension forfeiture amendment, Proposal 2, New Yorkers will then be on firm footing to pressure the State Assembly and Senate to take up other needed reforms. These should include closing the “LLC loophole” that allows the use of limited liability corporations to funnel massive amounts of cash into election campaigns, and banning companies and individuals bidding on government contracts from making campaign contributions to state elected officials who have authority to approve or reject those bids.

A big win this Election Day for Proposal 2 would demonstrate that the public wants ethics reform. Too many people in Albany believe that ethics reform is something voters don’t care about. Prove them wrong – vote YES on Proposal 2.

***

David Buchwald is a New York State Assemblyman from White Plains. He represents over 130,000 residents of Westchester County. On Twitter @DavidBuchwald.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Open Primaries and Overcoming the Racial Divide the Parties Prop Up

(photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

Today the dominance of the two major parties has frozen the country’s political development along a racial divide: the Republican Party uses law and order, tax cuts and anti-immigrant rhetoric to capture white voters, and the Democratic Party depends on high black voter turnout to win elections, while failing to address the ongoing inequality between people of color and white people. Pollster Cornell Belcher has found that 63% of black people feel taken for granted by the Democratic Party. The current highly partisan political environment is producing both government dysfunction and a general sense of dread that the county is moving backward.

The American people have been so manipulated and divided by politicians and our political process so over-determined by two-party control that for ordinary people of good will to meaningfully come together requires a wholesale break from politics as usual. We should not confuse multiracial solidarity—when people of different races come together to fight for a common goal—with the dynamic of political party constituency groups such as African-American, Latino, LGBT people, and women making demands within the Democratic Party and fighting each other for the attention and resources of the party and its elected officials.

I recently had a conversation with a close friend whose history is very different from my own. We agreed that perhaps the most dangerous effect of the current political environment is that people of different races are being pushed further and further apart. My friend Nancy, who is white, grew up under segregation in the 1950s in small towns all over northeast Arkansas. As a child, she "experienced and witnessed and joined the fight for integration in the South.” Fifty miles from her home and 20 years earlier, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union was formed, a federation of tenant farmers that united black and white sharecroppers to reform the system of sharecropping and improve the lives of all its members. Women played a key role in the development of this organization. As we talked about this, Nancy said to me, “I think this history is good to have in our tool box. I certainly will not forget where I come from. This history is important to me because I witnessed the fight for integration in the South.”

I grew up in the black community of south Philadelphia in the 1960s. My grandmother, Adell Chandler, owned and operated a large soul food restaurant that was open 24 hours a day and was a pillar of the cultural and social life of the community. She was a supporter of the civil rights movement and she encouraged me to become a doctor. I dreamed of becoming a doctor who could be a role model and help transform the conditions of the black poor.

I remember hearing Dr. King’s voice on the radio. It was his unbending stance for nonviolence, his courage, his willingness to sacrifice his life, his humble yet soaring commitment to fight against poverty, racism, and war that inspired people of all colors to take a stand. When Dr. King asked people to come to Selma to march for voting rights for African-Americans, Americans from across the country responded.

Nancy and I are both independents who are activists in the progressive wing of the independent political movement founded jointly by Dr. Lenora Fulani—who ran for president as an independent and in 1988 became the first woman and African-American to appear on the presidential ballot in all 50 states—and Jackie Salit, the author of Independents Rising and the president of Independent Voting, the country’s largest network of independent voter activists. These two women are working to build multiracial solidarity by creating independent tools to revitalize American democracy and transform our political culture to one of inclusion and opportunity for all.

Multiracial solidarity stretches throughout American history from the founding of the country in which black soldiers fought alongside white soldiers in the Revolutionary War, to the anti-slavery movement of black and white abolitionists who worked together and built the Underground Railroad. And examples from the Civil War, when Union officers like Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Robert Gould Shaw led regiments of black soldiers, many of whom were recently emancipated slaves (Shaw died fighting alongside his black troops).

A little-known demonstration that preceded the modern civil rights movement was led in January 1939 by Owen Whitfield, an African-American preacher and organizer of the Southern Tenant Farmer’s Union. He led the Missouri Sharecropper Roadside Demonstration, where black and white homeless sharecropping families camped out on the side of the road in the dead of winter as a means of getting the government’s attention to the vast poverty and injustice for tenants who were pushed off the land by planters. In the face of the segregated south they stayed together and though the public demonstration was crushed by the state police, it remains an inspiring example of poor people crossing the racial divide to stand in solidarity and demand justice.

Today in most states there is a political divide between the Democratic and Republican parties that corresponds to a racial divide in which people live in segregated communities.

A recent New York Times article on the obstacles to getting the governor, the mayor and the state Legislature to agree on a plan to invest in New York City's badly aging subway noted: "The future of the nation's busiest subway system, which has become engulfed in crisis, could well depend on New York State lawmakers…who live hundreds of miles from the city.”

The distance between New York City and much of the rest of the state is not only geographic, it is also a racial divide that is sustained by the parties. Though people of color live throughout New York State and New York City is racially and economically diverse, downstate New York City where more people of color live is dominated by the Democratic Party and upstate New York, where fewer people of color live, is dominated by the Republican Party. This arrangement maintains the parties’ duopoly control and both parties have carefully protected it, including through gerrymandering of districts.

In a closed primary state like New York, where party insiders control the process of voting, only party members are allowed to vote in the corresponding primaries. Over 3 million “independent” voters are excluded from primary voting as a result. Of those, 35% are millennial voters, 33% are Asian voters, 20% are Latino voters and 18% are African-American. Under these exclusionary, partisan elections, the New York State Legislature has proven itself to be one of the most dysfunctional and corrupt state governments in the country.

This November, New Yorkers will have an opportunity that only comes around every 20 years: to vote “yes” on a constitutional convention, through a ballot referendum question on Election Day, and break free of the constraints to begin a process that puts reforms such as open primaries in the New York State Constitution.

In contrast, California has nonpartisan open primaries, passed by the voters in 2010. The impact has been significant. People of color are winning some local elections in majority white districts and California is leading the nation in passing effective government reforms. Moreover, under its open system two women - one African-American and one Latino -- faced off in the general election for a U.S. Senate seat in 2016. Kamala Harris, the African-American of the two, won to become the junior senator from California.

Americans can only truly come together if we can build a democratic process that empowers all voters outside the framework of a political party. Nonpartisan structural reform such as open primaries provides that opportunity.

Forty-three percent of American voters now self-identify as independents and many people, no matter how they identify, want the chance to vote and to participate in politics in new ways. The government dysfunction we see in Washington will not be reformed from within the parties. The future of our democracy depends on the American people carrying it forward. Those stepping outside the parties are leading the way to build bridges rather than walls.

***

Dr. Jessie Fields is a Harlem based physician, an organizer with the New York City Independence Clubs and a board member of Open Primaries, which advocates for nonpartisan election reform.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.