City Must Act to Close MTA Funding Gap

(photo: @MTA)

Last month, the MTA submitted its five year capital budget. The $32 billion plan would provide critical funding for the replacement of subway cars and buses, the modernization of signal and communication systems, and major expansion projects like East Side Access and the Second Avenue Subway. While the capital plan is essential to the continued functioning of New York's century-old transit system, there was a hitch: $15.2 billion remains unfunded. How can the MTA close this gaping hole in its budget? With strong leadership and creativity from Mayor Bill de Blasio; wrangling funding from Albany and Washington while increasing the city's financial support.

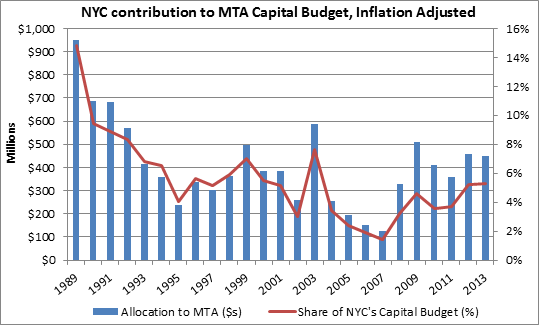

Over the last twenty-five years, the City's direct contribution to the MTA capital program has fallen markedly. In 1989, Mayor Ed Koch allocated $950 million to the Authority – representing a 15 percent share of the city's total capital budget. By 2007, that contribution fell to $124 million, a 1.4 percent share. And while the City's funding of the 7 Train extension - via the Hudson Yards Investment Corporation - provided a bump over the last five years, its $449 million contribution in 2013 was less than half its 1989 total.

With the 7 Train extension nearing completion, the city mustn't allow its funding to return to mid-2000s levels. In its capital plan, the MTA budgeted only $131 million per year from the city over next half decade. Mayor de Blasio should consider tripling or quadrupling that sum.

In the past, the City's allocation to the MTA has been highly targeted. During his final term, Mayor Koch made a generous contribution to replace the Transit Authority's aging and graffiti-stricken subway cars. Mayor de Blasio and the City Council should take a similar tact, devoting dollars to a specific priority.

Across the transit system, there are a number of urgent needs. According to the Center for an Urban Future's Caution Ahead report, for instance, 37 percent of the subway's signal system has exceeded its fifty-year useful life and approximately 1,000 subway cars running along the A, C and E lines were built prior to 1975.

The MTA's fare-collection system too, is nearly obsolete. Officials have warned that its MetroCard turnstiles cannot be maintained beyond 2019. As the Transit Authority begins to implement a contactless, smart-card payment system, the City's new Municipal ID card could serve as a platform. In Boston, Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) passes are built into the One Card for students. New York could fund a similarly integrated ID, helping the MTA adopt a modern fare-collection system while ensuring broad adoption of the new Municipal ID card.

The City can also help the MTA develop new funding streams. The second phase of the Second Avenue Subway, running from 96th Street to 125th, will be a boon to East Harlem developers. The City could follow London's lead, establishing a Community Infrastructure Levy on each square foot of new construction in the neighborhood. As developers profit from increased investment in public infrastructure, it is only fair that they contribute to this investment. The return on the levy could be divided between the subway extension and the city's affordable housing fund.

Importantly, the City cannot allow Albany off the hook. The current five year plan assumes zero capital contributions from the State. While Albany does contribute to the MTA operating budget, this is drawn from dedicated revenue sources that largely originate in New York City – like the corporate franchise tax surcharge and real estate transfer taxes. Discretionary funding for the MTA, on the other hand, was cut by $30 million this year.

Given that the city – and by extension, the subway – is New York's primary economic engine, this is unacceptable. Mayor de Blasio should work with Governor Cuomo, ensuring that any increase in the city's allocation be matched or multiplied by Albany – sourced, perhaps, from the state's new infrastructure bank.

The City should also press the MTA to more equitably distribute its capital funding across the subway and regional rail systems it operates. The 2015-2019 capital plan devotes 25 percent of rail funding to the LIRR and MetroNorth, despite the subway representing 91 percent of the Authority's ridership. If funding were divided according to ridership, the subway system would receive an additional $3.6 billion. Though perfect parity is not necessarily advisable, Mayor de Blasio should negotiate for a fairer distribution.

The subway is New York City's central circulatory system. Its 660 miles of track connect residents from Van Cortlandt Park to Coney Island, Flushing to Times Square. It is the thread that stitches the five boroughs together and a bellwether of New York's fortunes: as goes the MTA, so goes the city. To ensure New York's continued economic viability and quality of life, the upcoming capital plan must be fully funded. To do so, the Mayor and the Council – as well as the Governor – must take action.

***

Adam Forman is research associate at the Center for an Urban Future, a New York City based think tank. He is the author of "Caution Ahead," a report published in March by the Center documenting New York's infrastructure vulnerabilities.

***

@GothamGazette

Do you have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Send it to Executive Editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Staten Island WBE Grows Despite Geographic Challenges

Ford Wadsworth, Staten Island (photo: National Park Service)

The following entry is part of The Small Business Corner, a collaboration between Gotham Gazette and GoBizNYC:

GoBizNYC recently spoke with Ryan Walsh, President of Walsh Electrical Contracting, a long-established family-owned business based on Staten Island that continues to find new opportunities to grow and evolve thanks to the city's large and diverse market potential. The City's minority & women-owned business enterprise (M/WBE) program was key to the firm's most recent expansion. Walsh participated in the record $690 million in city contracts awarded to M/WBEs by the de Blasio Administration last month, a figure that has much room for growth, according to recent analysis of the program by Comptroller Stringer. The company's experience shows that, while New York City businesses face significant challenges, they also have great opportunities, especially when government is committed to supporting its business community.

Tell us about your business.

Walsh Electric was founded in 1979 by my parents, Kevin and Linda Walsh. They joined Local Union #3 of the IBEW and began serving the residential and commercial markets on Staten Island. I grew up in the business, working on weekends and during school breaks. After college, I owned and operated my own businesses. In 2011, my father's health began to deteriorate, and I returned to work at Walsh Electric so that he could have open heart surgery. He passed away unexpectedly later that year.

My mother and I decided to continue to operate the business. Now that my mother was majority owner, we felt the next logical step was to become part of the city and state certified WBE programs. In 2012, our WBE application was approved. Since my father's passing, we have grown 300% to over $20 million in sales and today we employ over 100 people in the field and the office. We are licensed by the City of New York and work exclusively in the five boroughs.

How has being WBE-certified helped your business?

Being a WBE enabled us to expand into the public sector. We have been involved in projects for Hurricane Sandy recovery as well as the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA), and the School Construction Authority (SCA). Many agencies require that prime contractors hire M/WBE firms as part of their contract agreements and Walsh Electric can fill that void. Today, about 25% of our business is made up of WBE work. That equates to roughly $5 million per year – revenue we wouldn't have without the WBE certification. This has allowed us to hire an additional 25 employees.

What are the opportunities of operating your business in NYC?

Operating an electrical business in NYC has many opportunities. This is the country's biggest market and there is a lot of development activity, whether it's new construction, renovation, or maintenance. All of this requires electrical contractors.

NYC is the premier place to live and work, so people will always be here, always want to be here, and will always demand the newest, best, and most exciting experience. In addition, the city's extensive waterfront and as well as inland rezoning have allowed for development beyond anyone's imagination. Plus, as technology advances, there will be greater demand for LEDs, electric cars, and wind and solar power. This will, in turn, only increase demand for electrical contractors.

What are the challenges of operating a business in NYC?

Logistics are tough. Being based on Staten Island while performing most of our work in other boroughs involves a big expense in gas, tolls, and time. Another challenge is that there is a lot of competition and when there are periodic slowdowns in the economy and construction activity, it hits us. High city and state taxes are also a burden.

Construction in the city is complex and involves a lot of permits, penalties, regulations, and inspections that drive up costs. For example, the Department of Buildings has been frequenting sites more often, leading to more fines and delays. There are a huge number of government agencies to deal with and there are lots of bureaucratic obstacles, such as getting approvals for design changes from the MTA, that lead to long project delays.

In what ways can local government better support your business?

Staten Island is going to benefit from the development of Empire Outlets and the New York Wheel, with the support of state and local government. But the City could do more to promote and support business and development activity here in Staten Island. New neighborhoods, such as Williamsburg and DUMBO in Brooklyn, are flourishing because of high density, vertical development, and good public transportation. This does not exist here. Traffic is a major issue. Expensive tolls and long commute times are a deterrent to people living and working here. As a result, Staten Island and its businesses have not gotten the same benefits of population and job growth as the other boroughs.

Staten Island's local officials are doing a great job for us. The challenge is getting the rest of the City to recognize us. Although we are one of the five boroughs, we are often forgotten.

***

Victor Wong is the Director of Business Outreach & GoBizNYC at the Partnership for New York City

To make or discuss a submission for The Small Business Corner:

Reach GoBizNYC Director Victor Wong at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Reach Gotham Gazette Executive Editor Ben Max at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Small Business Corner is a bi-weekly column featuring the opinions and perspectives of small business owners and advocates from the GoBizNYC network on the range of issues that concern the city's small businesses.

To all New York City small business owners and advocates: we hope this new platform, The Small Business Corner, will better enable you to engage in the local policy conversation and we look to you to support us in this endeavor by sharing your thoughts, experiences, and voices. To learn more about how you can be a part of GoBizNYC and participate in this effort, visit GoBizNYC.org.

Back-Stage Blood-Sport: Robert Carroll's The Believers

The campaign manager (both photos: Michael Abrams)

The hoary axiom that "politics ain't beanbag" is most often used these days when a candidate hits an opponent's character hard. But beanbag refers not just to a soft object that won't hurt; it's also a game with agreed-upon rules. And whether to play by, bend, or break the rules makes for good drama, whether on the campaign trail or stage. Working in the tradition of Gore Vidal's 1960 classic The Best Man, playwright Robert Carroll applies these questions to the rough-and-tumble world of New York City politics.

Set in Bill de Blasio's former city council district in and around Park Slope, Carroll's The Believers explores the world where most decisions get made: campaign headquarters. It's here where lead staffers hash out battle plans, often without the candidate's direct input. Carroll's play uniquely captures the adrenaline-rush felt inside campaign HQ as the day of reckoning approaches. And the Storm Theatre serves up a strong, fast-paced production, one that anyone interested in politics will likely appreciate.

Carroll, nearing 28, has grown up in city politics (and is currently the president of Central Brooklyn Independent Democrats). I asked to him to explain some background of the piece.

Your play is addressing a key ethical dilemma that arises in campaigns regarding 'how low will one side go?' in order to win. But most campaign decisions are really based on cold practical calculations. So are the "believers" here the starry-eyed idealists?

Practicality and idealism are often times thought of at opposite ends of the intellectual spectrum, but I think the play actually shows how idealism can lead to extremism and how those convictions can make people do terrible things under the guise of practicality. The main character betrays his idealism at the beginning of the play because he is so sure of the righteousness of his own beliefs. The conflict of the play revolves around whether the campaign will engage in defaming its leading opponent with a salacious piece of campaign literature on the morning of Election Day in hopes of suppressing Hasidic turnout in Borough Park. The main character—Chris, the campaign manager—justifies to himself that his decision to do the underhanded is morally valid because he believes the other side is so bad that no matter what he does the other side would be worse if they were to win. Of course, that underhanded and possibly practical choice made by Chris causes his downfall.

Your bio in the program says that you've worked on "countless campaigns" but the other night I sat next to Josh Skaller (currently a district leader in Brooklyn). He said that the storyline is an amalgam of a few specific races. Can you explain which ones?

I would say the play is part amalgamation of multiple campaigns, some of which I rely on more than others for reference points. However, many parts of the play are completely made up. I use my own experience to give authenticity, as well as build on, the larger metaphor about what people are willing to do for their beliefs. A political campaign is part marketing and part debate. Josh Skaller's 2009 city council campaign (against Brad Lander) was used as a foundation for the composites of some the characters and action in the play. I used some of the individuals who worked on that campaign because I personally respect them intellectually and fortuitously their sensibilities and conflict happen to be somewhat divergent from one another, which helps create dramatic conflict.

One of the characters was drawn from a 2010 congressional campaign I consulted on. And I also learned from my father, Jack Carroll, and his campaign work as both a candidate and an election lawyer. The play takes place in a very specific time, which I would rather not divulge since it is not readily apparent and is key to the conflict of the play. But I think it is important to note that I have had many politically astute people come see the show and many have thought certain references were in reference to different people or campaigns. I think this shows the universality of the themes and actions.

In the play, Chris (played convincingly by Taylor Anthony Miller) wrestles with the fact that his dad is a highly principled person. Are there any lessons he conveyed to you about the importance of staying clean in a dirty game?

I think the central question of the play and the central reason I am interested in politics is answering the question of "how" decisions are made, or the "process." I think if you are going to be involved in politics you should ask yourself 'how do we get where we want to go?' and 'how do we have a more fair system?' The play asks whether process/how we get somewhere is more important than holding the same beliefs as someone. So yes, my father instilled in me and my brothers a sense of fair play and honesty, and that process is very important. And that's what Chris is wrestling with.

As de Blasio's campaign illustrated, so much of politics is about stagecraft--e.g. the LICH arrest, Dante's hair, etc. But your play is about what goes on backstage. What made you decide to give the actual candidate such a minor role?

I wanted to allow the audience to imagine what the candidate was like, in order to create in their mind why these characters would do so much for this mysterious person. Furthermore, I didn't want the themes of the play to become muddled by making it about the personality of the candidates. You mentioned the de Blasio campaign's Dante ad as an example of political stagecraft, and while I agree, that ad also focused on Dante, not the candidate. I think lots of campaign theatrics do not revolve around the candidate but the message or themes they convey. I think often times people project their own feelings or hopes onto a candidate in the belief that it will fulfill something they desire.

***

The Storm Theatre's production of Robert Carroll's The Believers (directed by Stephen Logan Day) runs through November 1 at the Theatre of the Church of Notre Dame in Morningside Heights.

***

Theodore Hamm is chair of journalism and new media studies at St. Joseph's College in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn.

@HammerDaily